Rabbit Fever is the common name given to a bacterial disease called tularemia. It can be serious, though it is rare. Lagomorphs like rabbits and hares can carry the disease, as well as rodents and other animals. Insects help it spread. The Rabbit Fever I have, however, is the desire to hunt more species of rabbits in more states.

I am on a “Rabbit Slam” of sorts. I have successfully hunted the eastern cottontail, Appalachian cottontail, New England cottontail, swamp rabbit, and varying hares, and have hunted from Maine to Alabama. Summer marks a lull in the action when I can train my beagles but can’t hunt. Unless . . . I go somewhere that doesn’t recognize rabbits as a game species and allows year-round hunting of the critters, viewing them as pests.

Now, would I travel to one of those states just to hunt bunnies? No, of course not. That would require approval from marital court. Marital court is not the same thing as a court martial. The latter is part of a military legal proceeding with potentially serious consequences. Marital court is when my wife, Renee, puts me on trial for my actions, and the consequences are always serious. She is judge, jury, and prosecuting attorney. From what I can gather, I have no legal representation. Buying a fine side-by-side shotgun, scheduling a fishing trip without consulting her, and being late for supper because I was dragging a deer out of the woods have all landed me in court.

“The Outdoor Writers Association of America is meeting in Montana this year,” I said casually over morning coffee last May.

“I’ve never been there!” Renee delighted.

“Why don’t we drive it?” I asked. “See the country, and maybe take a side trip to Glacier National Park? It will be cheaper than two plane tickets.”

Did you notice how I appealed to her sightseeing passion and her fiscal responsibility?

Oh, by the way, my research department (Google) told me that I could hunt rabbits in Montana and North Dakota all year. Two days before we departed, I removed the large dog box from my truck bed—it will haul a pack of dogs—making room for more storage and luggage. The conference itself would be in a hotel from July 15-18, and I knew that for a modest fee of $25/dog I could keep a pooch in my room. I couldn’t imagine walking four beagles to the hotel yard for bathroom breaks, so I decided to take just one dog. For a mere $25 extra I took Duke, and put a small plastic crate in the backseat of my Tacoma for him to make the long commute to Montana from Pennsylvania, watering and fertilizing various truck-stop trees in between.

The plan was to hunt for the whitetail jackrabbit in North Dakota and the mountain cottontail in Montana. Both species are new to me. I figured summer would be too hot for chasing the desert cottontails of Montana. Marital court was in session when my wife saw the shotgun case was packed. It was made a capital crime when she saw the small, plastic dog box in the backseat.

I pleaded to the court for mercy: “All I want to do is shoot one jackrabbit and one mountain cottontail. I want to send them to the taxidermist, because no one around here has seen either species. Then I am done hunting. Just two shots. I promise.”

“Okay,” she sighed.

Cacti are a problem for both the hunter’s and dog’s feet.

We arrived at the Lone Tree Wildlife Management area at 5:30 in the afternoon on the second day of our trip. I was told by a North Dakota biologist to try this spot. It was a little windy, meaning my hat would not stay on my head. Duke’s ears looked like wings. The grasses looked like waves of water and had a disorienting effect on me. I could not hear his bell, even at 20 yards. I have heard the same bell at well over 200 yards on a cold, calm winter day. I had to use the GPS collar to know where he was. We never jumped a rabbit in four hours.

I went to the office the next morning, hoping that the wind accounted for the lack of game. They said that they had not seen a jackrabbit in years. Also, they thought I was crazy.

“You’re hunting what?” the lady asked me.

“Jackrabbit,” I answered.

“Why?” her eyes bugged open.

“I have beagles, and I brought one.”

“What for?” She looked at me the way you might question a person wearing a parka on an Alabama August afternoon.

“To chase the rabbits.”

“Why?” her voice quivered with concern.

“To shoot them.”

“Why?” she seemed rattled.

“Well, in this case just to get a taxidermy mount, but usually I eat them.”

“Try the Western part of the state.”

Remember that tularemia? There are Westerners who believe every rabbit has the disease, and that looking at one might kill you. I once had a Rocky Mountain friend say, “The only place where you can safely eat a rabbit before winter is the Yukon.”

“Nah,” I said, “I have killed them in the late October afternoon, weeks before the first frost, let alone winter.” He backed up ten feet. It probably was a bad coincidence that I coughed at the end of the sentence when I told him this truth, but I had some coffee “go down the wrong pipe” just before we started talking.

I digress. It was too late to hunt western North Dakota that day, so I decided to either hunt it on the way home or maybe get a jackrabbit in Montana, as well as the mountain cottontail. We drove straight to Billings, Montana, and got our room. I knew I had to take my wife for a nice dinner, so we went downtown and left Duke in the hotel.

The next morning, we got up and headed for the Yellowstone Wildlife Management Area to look for jackrabbits, based on another tip from a biologist. I think he chased one. The ground was bone dry, and he didn’t let his voice—a gorgeous rolling bawl—fill the air. But he looked serious. He ran out over two miles, then came back. I went back to the truck and gave him water and we rested for a few hours.

I took my wife, who patiently waited while we hunted, to dinner. Upon returning to the area, I took Duke down to a wet area and we started working cover. Instead of briars, I saw cacti. Instead of groundhog holes, there were prairie dog holes. Then I heard Duke bay and off he went! He was slow. A walk really. The chase ended 100 yards away in the middle of what appeared to be a prairie dog city. This happened a few times. Was he putting cottontails in the hole, or were the large leaps of the jackrabbit too much for him to handle on a July evening in poor scenting conditions? Then Duke jumped a rabbit that actually did what rabbits do—circle.

The first circle had the rabbit pass 60 yards away, and I did not see it. The circle was small enough, however, for me to realize that this was not a jackrabbit—he was never further than 250 yards away, according to Duke’s tracking collar. He circled out in another direction. I had a bit of anxiety about the potential of the rabbit running up a butte and Duke falling like the coyote in a Road Runner cartoon, but this circle was even smaller.

I am sure this rabbit had never been chased by a barking hound. It had no idea why the slow-moving thing behind it was not silent and quick like a coyote. I noticed it doing the slalom through the prickly pear and other needle-encrusted, low-growing cacti. It turned around to look at its pursuer, and my A.H. Fox 12 gauge ended the chase. One shot from the right barrel and it leaped forward, dying within a foot of a prairie dog hole.

Prairie dog holes replaced the groundhog holes the author was used to when rabbit hunting.

I was as ecstatic as when I killed my first whitetail buck. Speaking of deer, I called the taxidermist who wanted to do a shoulder mount on the buck I shot last fall. He gave me a good price, too, but in the end I removed the skullcap and put the antlers on a cheap wooden plaque. He lamented that I did not at least get a European mount.

“Hey,” he answered the phone as I called from my truck, riding down a dirt road in Montana. “What’s up?”

“I am going to overnight-ship a rabbit to you on dry ice from Montana,” I blurted out my words with enthusiasm.

“That is going to be expensive just to ship it. I will give you a good deal, though.”

“Sounds good,” I said, “What is the address?”

My wife wrote down the address and we hurried to get dry ice. He was right about the shipping, too. It was a couple hundred dollars!

“You make no sense,” he said when I called to confirm that the mountain cottontail had arrived. “You had that nice 9-point last year, and you are paying me for a rabbit mount?”

“Yeah,” I beamed, “It will look good next to the varying hare and the swamp rabbit. A real trophy—these scenting conditions are horrible here!”

I spent the whole conference elbowing with other writers. They whipped out their cell phones to show pictures of trophy trout. I showed them pictures of Duke, me, and the mountain cottontail. They looked at me like the lady in the North Dakota office did. One of the writers was from the West asked, “You touched that thing? In July?!”

“Yeah,” I said, “Look at that tan spot on the back of the nape! That is never seen back East. What a great hunt.”

He backed away from me with trepidation.

A new rabbit toward the author’s slam.

The annual gathering of outdoor communicators was great fun, and I made the promised trip to Glacier National Park with my wife. On the return trip it was over 100 degrees and too hot for Duke to safely hunt—if he could even smell the rabbit on that parched, hot ground. I decided not to try for the jackrabbit.

“Darn.”

Renee rolled her eyes. “Too bad.” She evidently shared in my dejection at the lost chance.

So I never got to see a jackrabbit. That’s okay. Maybe I will go back in the winter. Not only is the scenting better, but I have dogs that have learned to look for rabbit tracks in the snow. As a bonus, the whitetail jackrabbit will be in the white phase then—a much prettier coat. Plus, I can let the North Dakota winter freeze it for me and take it to my taxidermist to save on the shipping costs. That will be cheaper, but I am not sure if showing up at his house with a frozen jackrabbit will make me look more reasonable or crazier. I have only been home a day from the western trip and I am wondering about the roads in winter. It’s that Rabbit Fever!

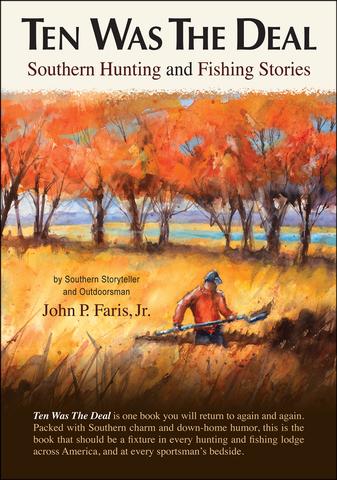

Ten Was The Deal is more than a book of stories about hunting and fishing, it offers all of the enchantment of yarns spun while sitting on the tailgate of a pickup truck; all of the lore of tales told around a campfire. Ten Was The Deal is definitely a keeper.

John’s stories are set in pinewoods, along Piedmont streams, in Lowcountry fields, or along the coast of the Carolinas. This volume reveals a boy’s journey to manhood: turkey hunting with a grandfather, duck hunting with a dad, and sharing his first kiss with a fishing buddy. Buy Now

Looks like a 12 GA, is that what your using on the rabbits?

Love to hunt rabbits, love to listen to good beagles giving chase, and loved the story. Thee is another species you need to try — the marsh rabbit found in coastal counties and on marsh islands along the Carolinas-Georgia coast. Smaller than a cottontail, with shorter ears, and can swim like an otter!

I can’t wait to get some cottontail time this November, I bought a case of RST 2 1/2″ paperhull shells just for the occasion.