Legendary dog trainer, Al Brenneman, promoted a simple, straightforward, common-sense approach to starting a puppy in the field.

The best part of doing what I do is the cast of characters it’s allowed me to rub elbows with along the way. In other words, it’s the people. And if there’s one category of people that I feel especially privileged to have mingled with—and mined for all the ore I could— it’s the old-time professional trainers, the men who came up during that Golden Age when there were birds to hunt pretty much everywhere (even in places like Long Island and Cape Cod). Back then, mainstream magazines like Saturday Evening Post and even Life ran stories on bird dogs and field trials, and the names of the great champions and their handlers were on the lips of sportsmen from coast-to-coast.

It wasn’t simply a different time; it was a different world.

Sadly, only a handful of these legends remain. There’s the irrepressible Delmar Smith, who, the last time I caught wind of him, was preparing to take his girlfriend on a cruise to South America. If I’m not mistaken, Delmar turned 92 on his last birthday. Pretty much all of Delmar’s contemporaries, alas, have gone to their rewards, their legacies left to be sorted out by history.

One who deserves to be better remembered, in my humble opinion, is A.H. “Al” Brenneman, who maintained a training kennel in Frankewing, Tennessee, for many years prior to his death in 1996. Al was 88 when he passed, so you can’t say he didn’t have a good long run. He published a well-received book, Al Brenneman Trains Bird Dogs, in 1983, but his chief claim to fame is that he was, by a mind-boggling margin, the greatest curer of gun-shy dogs who ever lived. By Al’s own estimate, he rehabbed some 4,000 gun-shys over the course of his career.

That is not a misprint.

Al was so good at it that he offered a “no cure, no pay” guarantee (the first pro ever to do so). Eventually, he became so renowned that gun-shy dogs were sent to him from as far away as France. He also did a lively business as a “subcontractor,” curing gun-shys for other professional trainers who, lacking the time and/or expertise to do the job themselves, figured it was more cost-effective to hand it off to Al.

Despite all the dough he pocketed from the gun-shy trade, Al was adamant that an ounce of prevention—in the form of proper introduction to the gun—was worth a pound of cure.

One of the things he and I were in total agreement on was that the gun, from the beginning, should be associated exclusively with birds. Not only is this the best (and safest) way to accustom a dog to gunfire, it forges the all-important gunfire-equals-birds connection. Al took a very dim view of the oft-repeated advice that you should introduce the gun during feeding time, and he used a wonderful anecdote to prove his point:

“I was having a steak in a restaurant in Rock Island, Illinois, when a gunfight broke out in another part of the dining room. I’ve been gun-shy ever since!”

While curing gun-shys and other “problem” dogs—blinkers, bolters, etc.—was Al’s bread-and-butter, the thing that made him eager to roll out of bed every morning was starting puppies. While not as renowned in this respect among the sporting public at large, among knowledgeable bird dog people his reputation for developing young dogs was second-to-none.

While curing gun-shys and other “problem” dogs—blinkers, bolters, etc.—was Al’s bread-and-butter, the thing that made him eager to roll out of bed every morning was starting puppies. While not as renowned in this respect among the sporting public at large, among knowledgeable bird dog people his reputation for developing young dogs was second-to-none.

A few years before his death, Al sent me a multi-page, handwritten manuscript detailing his method for starting a puppy. It was festooned with gems.

“The most important thing to get across is that a puppy can do no wrong—even if he gets into your best laying chickens” was one; another was, “For class in bird dogs, you have to keep the going in them fiery.”

Because Al’s method has stood the test of time, I thought it’d be fun (also instructive and enlightening) to dust off Al’s manuscript and share its enduring wisdom. To wit:

- The more frequently you can get your puppy in the field, the better—but keep workouts short. Ten to 15 minutes is plenty for a young pup, especially if he’s fortunate enough to enjoy a bird contact.

“Don’t wear the pup out,” Al advised. “You want it to remember fun and excitement—nothing else—so that he can hardly wait until his next workout.”

- Choose fields that aren’t close to roads, livestock, or other potential dangers/temptations. You should avoid situations in which the pup can get himself into trouble— and that might force you to assume the role of disciplinarian. (I think Al would approve of my suggestion that you should also use this time to accustom the pup to wearing a GPS collar. A lost puppy is a tragedy waiting to happen.)

- Do your best to work your puppy into likely bird-holding cover: hedgerows, thickets, field edges, etc. “Once the pup has found a few birds,” Al wrote, “you’ll notice him starting to search out birdy places on his own. Then you can begin to hang back and allow him to hunt the cover.”

This point can’t be over-emphasized. You can accomplish a lot of with pigeons, but exposure to wild birds is the only thing that can teach a dog how and where to hunt.

- Try to walk in a zig-zag fashion when your pup’s in the field. It helps instill a natural quartering pattern, and it gets the pup in the habit of occasionally checking on your whereabouts. You can even use hand signals to indicate to the pup that you’re changing direction. It’s amazing how quickly they pick up on that—and it’ll pay incredibly dividends down the line.

- Don’t run your pup with a bracemate until, in Al’s words, “he’s begun to regularly find birds on his own and is starting to look a little businesslike in workouts.”

- Use the pup’s name often, especially at feeding time and when you’re petting him and generally “loving him up” (which you should do as often as you can). That way, he’ll always associate his name with pleasant sensations— and you’ll be ahead of the game when it comes time to begin serious yard training.

- Don’t push staunchness on point. If there’s one area in which it’s easy to be in too big of a hurry, this is it. “This is a time to build excitement,” Al stated. “Most pups will flash point, flush their birds, and chase them— exactly what you want them to do at this stage. But if your pup does go on point, don’t stroke him and fuss over him. Instead, run in, flush the birds, and encourage him to chase. It could be that the pup’s a little timid; if so, this will make him as bold as a lion.

“Then, when he’s chasing strongly, you can introduce the gun. There’ll be plenty of time later on to make him staunch.”

One additional note regarding your puppy’s early contacts with game: Whenever your pup gets into birds—points them, runs them over, busts and chases, whatever—give the two-note “bob-white!” whistle. The sound will soon come to mean birds here; later, you can use it to instruct your dog to hunt close or simply as a kind of stimulus to encourage him to ramp up his intensity. • Don’t experiment. “I’ve heard so many amateurs say, ‘I think I’m going to try something new.’” Al recalled. “Well, that’s just asking for trouble. It’s okay for us professionals, because we know that if we make a mistake, we can correct it. Often as not, when an amateur of my acquaintance thought he’d try something new, I took another $500 to the bank. Amateurs should go by the book.”

- Be patient, never hurry, and remember that each dog is an individual with quirks and foibles all his own. That’s all there is to it: a simple, straightforward, common-sense approach to starting a puppy in the field. No gimmicks, no shortcuts, nothing “revolutionary.” But then, nowhere does the adage “Everything old is new again” ring truer than in bird dog training.

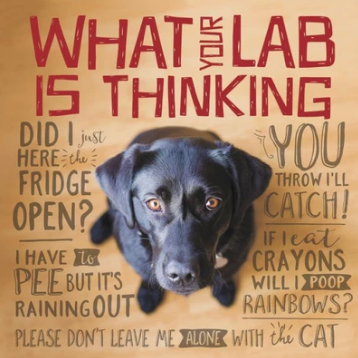

Labs are known for their furry snuggles, playful romping and soulful eyes; just think if they’re tongues were wagging instead of their tails! This playful little book is full of side-splitting inner monologues about a lab’s favorite things, the people they meet and places they go. The bold colors and lighthearted quips are paired with an array of adorable yellow, black and chocolate dogs and puppies, making this the perfect gift book for anyone who’s ever loved a lab. Buy Now

Labs are known for their furry snuggles, playful romping and soulful eyes; just think if they’re tongues were wagging instead of their tails! This playful little book is full of side-splitting inner monologues about a lab’s favorite things, the people they meet and places they go. The bold colors and lighthearted quips are paired with an array of adorable yellow, black and chocolate dogs and puppies, making this the perfect gift book for anyone who’s ever loved a lab. Buy Now