Decades of earth’s annual renewal have come and gone since that magical moment when I stooped almost reverentially to admire my first wild turkey, and there have been untold thousands of daybreaks greeted amidst the greening-up wonder of spring. From that first morning a corner of my sporting soul was hopelessly lost to his majesty, the wild gobbler.

Thanks to a wise, far-sighted mentor named Parker Whedon—a true old master of the sport—I have a tangible, deeply meaningful way of looking back on the most significant of those special springtime moments.

Parker was with me when I killed that first turkey, and, truth be told, he did pretty much everything but aim the gun and squeeze the trigger. When a bird gobbled on the roost, he eased me into position alongside an old logging road, indicated the turkey’s likely travel route, and whispered, “When he passes that stump, he’ll be close enough to shoot.” Although time has proven to me that about the only thing predictable when it comes to hunting turkeys is that everything is unpredictable, on this particular occasion things unfolded precisely as he predicted. In less than a half hour we were admiring a fine gobbler with the first rays of morning sun flashing off its feathers.

As I relived the moments leading up to the shot (Parker had moved behind me 50 yards or so to call and did not see the moment of truth), Whedon offered a simple comment which has, over time, become most meaningful.

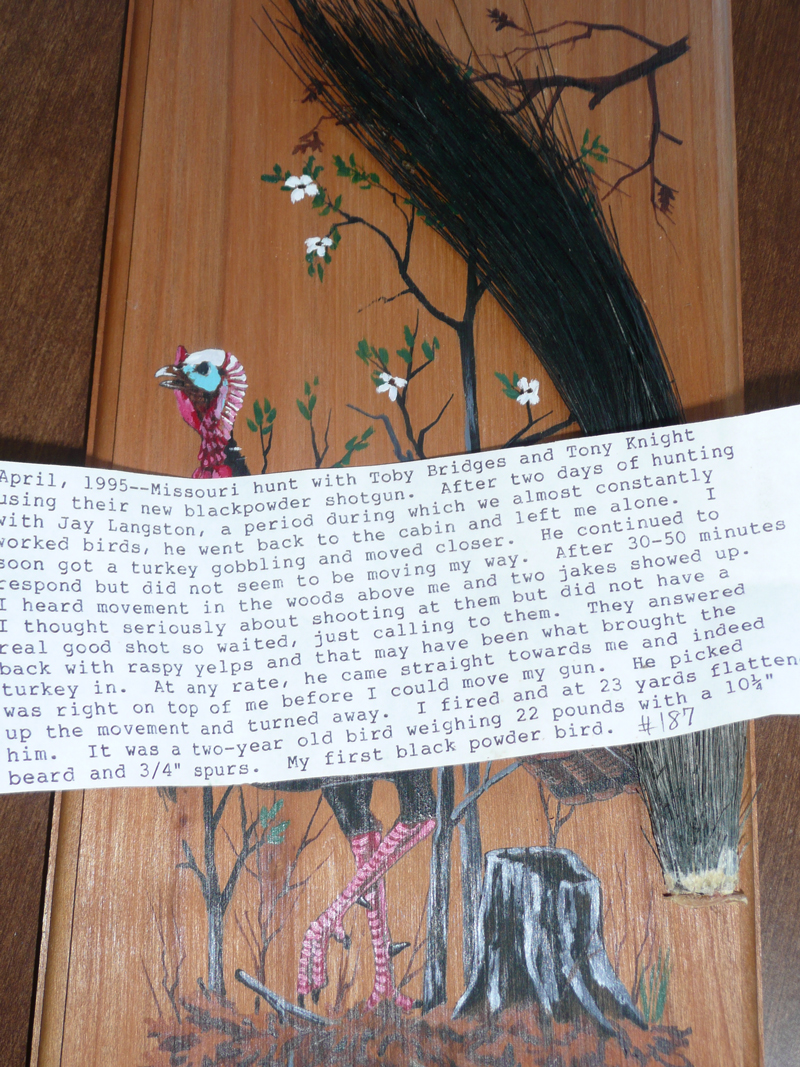

“Let’s go back to your set-up position and find the shotshell,” he said. “If you come to like turkey hunting as much as I think you will, there’ll come a time when you can’t remember every turkey you’ve killed. However, if you save the hull, write up a little story about the hunt, and insert that tale and the gobbler’s beard in the empty shell, you’ll have a memento of great value. All you’ll have to do is pull out the shell, unroll the little scroll describing the hunt, and suddenly you will experience a wonderful moment of travel back in time.”

I took his advice and, indeed, absorbed everything this icon of the turkey-hunting world offered me for many seasons to come. Mind you, Park was a tough taskmaster. Along with giving me the advice about preserving memories of the hunt, he had another pithy comment to offer on that initial outing.

“That’s how it’s done,” he said. “Now you are on your own.”

I did not kill another turkey that season, although there were plenty of opportunities thanks to the hunt club to which I then belonged being eaten up with longbeards. Repeatedly over the following weeks I would call him in the evening with my latest story of miscues, mess-ups, misses (three of them), missteps, and general misery. He would listen patiently, chuckle a bit at my misfortune, and then quietly suggest a tactic or two I might have tried.

A story without a shell—the author’s first blackpowder gobbler.

Patience and persistence began to pay dividends the following season. I killed two birds (South Carolina regulations have long permitted this) and was in effect off and running. Over the ensuing years, and there have been a lot of them, I’ve hunted in somewhere between 30 and 40 states and two foreign countries, and two years ago I reached the 300-turkey mark in my career.

That shouldn’t suggest I’m a master hunter, because I’m not, but I’ve paid a great deal in the way of dues through boots on the ground, learned from some of my mistakes, although they still bedevil me as they do every serious turkey hunter, and have possibly reached what the great, old-time turkey man Archibald Rutledge called “the kindergarten stage.”

He used that description in a story entitled “My 337th Gobbler,” but I’m going to give myself some extra credit for having read a great deal on the sport (and its literature is far richer than was the case in his heyday). I’ve written three books and hundreds of articles on turkey hunting, remain a starry-eyed youngster as opening day approaches each year, and don’t mind admitting I’m hopelessly addicted to the grand quest.

The author with a fine North Carolina gobbler.

For all of that, I owe a lasting debt of gratitude to Parker Whedon, but of all the manifold gifts he presented me in terms of wisdom, elegantly crafted wingbone calls, plainspoken instruction, and pithy commentary on the natural world in general, nothing quite matches his advice on preserving my turkey memories. Seldom does a week pass when I don’t dig into one of several “beard boxes” holding these mementoes, dig out a shell at random, and read the story. As soon as I do so, my footsteps become a bit lighter and my outlook a whole lot brighter. However, if somehow all those marvelously misspent years in the turkey woods could be retrieved, and if the boundless energy which once seemed a given could be miraculously retrieved, I’d do one thing differently. Along the steps outlined above, I would take a photo of the bird to capture one more aspect of the overall experience.

But in turkey hunting, as in life, you can’t call back yesteryear.

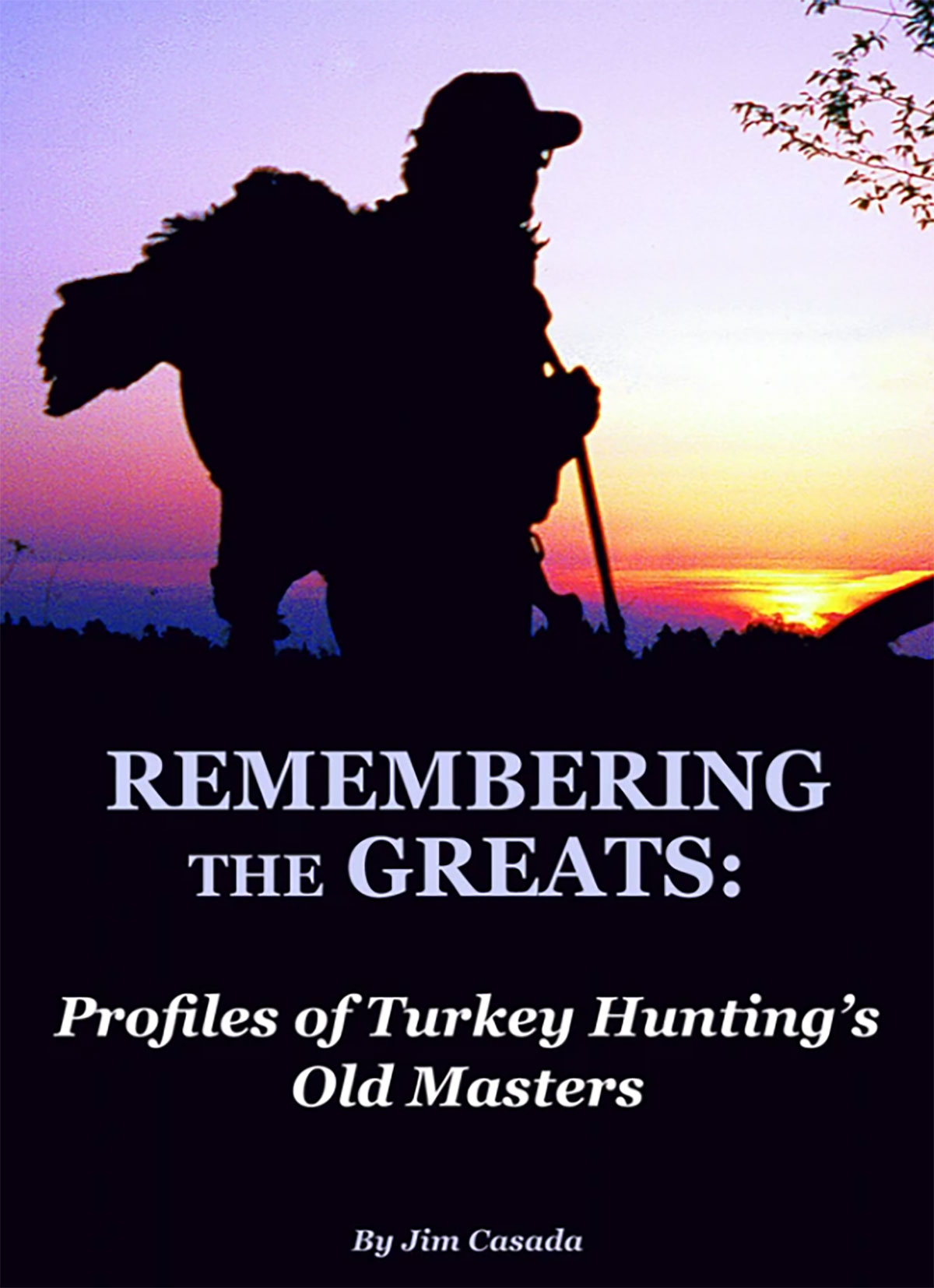

Jim Casada, Sporting Classics’ longtime editor-at-large, has written extensively on turkey hunting. His efforts include: Remembering the Greats: Profiles of Turkey Hunting’s Old Masters, The Literature of Turkey Hunting (a limited-edition, numbered, and slipcased volume) and more.

Remembering the Greats

In Remembering the Greats, a 317-page hardbound book, Jim Casada brings his training as an historian, his decades of studying the grand masters of the sport, his avid collecting of the literature, and his personal hunting experiences to bear in a detailed examination of the careers of 27 icons from turkey hunting’s past. Collectively they epitomize the essence of what old timers sometimes refer to as true “turkey men.”