As someone who spends a lot of time working to preserve late 19th century and early 20th century double guns, I have thought a lot about why some high quality and once very expensive shotguns have been well preserved and others have not.

The formula for the preservation of antique and vintage shotguns is the same as for other complex machines:

1. Recognition of value, tangible or intangible

2. Periodic, if not regular, use

3. Routine operator-level maintenance

4. Scheduled preventive maintenance services.

The last condition is, in my opinion, the most significant in preserving vintage and antique double guns that have made it this far but are now at risk.

Our double guns are many things to us, but at their core they are fine machines made of steel and wood. At some reasonable interval all fine machines, if they are to function properly over long periods of time, need to be taken apart, cleaned, inspected, fully serviced and major elements repaired or replaced before they fail completely.

A majority of the vintage shotguns that people bring to me for servicing or reconditioning are their father’s or grandfather’s guns that they want to pass to the next generation. Or they come from people who have more recently acquired an antique shotgun because they want to preserve a piece of our shooting heritage. Many of these shotguns appear never to have been fully serviced, or at least not in a very long time. As with all fine machines, 100 years is simply to long between scheduled maintenance services.

Most of these double guns can be brought back to be functional and beautiful. The case-hardened steel of the receivers can withstand a lot of punishment or neglect without major damage, as can the high-carbon tool steel used to make key parts of the locks and actions. The Damascus-steel and fluid-steel barrels of this period are robust and can almost always be saved if there is enough wall thickness. The wood is the most vulnerable.

In my experience, the greatest single threat to the preservation of 19th and early 20th century shotguns is petroleum-based oil that has accumulated in stocks and forearms. Ironically, owners, in their efforts to provide good operator maintenance, can contribute to the problem by heavily oiling barrels and receivers and then storing guns with the butt down. Gravity carries the damaging oil into the stock. Also, when owners do not thoroughly wash their hands after cleaning the barrels of double guns before putting them back together, they transfer cleaning solvents and gun oil directly to the checkering on the wrist and forearm. These are two of the most damage-prone areas. Also, a generation ago it was also not uncommon for owners to apply cleaning solvent and other petroleum-based products directly to the wood to make it shiny.

Petroleum-based oil causes the wood to discolor, soften and lose strength. The effects, in the order of their occurrence and severity if left untreated, are:

1. Concealment of the natural beauty of the wood

2. Loss of checkering, excessive dents and deep gouges

3. Structural damage in the stock head and wrist.

In the first column, pictures 1 and 3 show portions of the stocks before reconditioning of an L.C. Smith Baker-Patent 3-Barrel, Quality-3, 10×10/44-40 gun and a Parker Brothers Quality-2 Top-Action 10-gauge hammergun. In both stocks the nice figure is obscured, the wood looks dirty, the surface is scratched and the checkering has become smooth. In the column at right pictures 2 and 4 are of these stocks after reconditioning.

This dramatic difference is primarily the result of a process that can be thought of as an oil change, with linseed and other natural plant oils replacing the contaminating petroleum-based oils. This change is accomplished by taking off the old finish, drawing out petroleum-based oils by soaking in acetone, steaming and other techniques, removing the oil-damaged wood, sanding out dents and gouges as much as possible without changing the nature of the gun, making necessary repairs to the wood and restoring natural oils by applying a hand-rubbed stock-oil finish. If the wood containing the checkering is not too damaged, it can be cleaned and deepened, otherwise the checkering must be sanded completely off to get down to healthy wood and new checkering cut.

I am a gun rescuer at heart and will occasionally buy an antique gun simply because it is at risk. The Nichols & Lefever, shown in pictures 5 and 6 before reconditioning, is such a gun. The grain of the wood in the stock body is obscured. The wood in the wrist is discolored and what is left of the checkering is basically being held together by the finish. The stock head is almost black with petroleum-based oil.

Indicators of the amount of petroleum-based oil that was in the wood before reconditioning are captured in pictures 7 and 8. The tray in picture 7 shows the acetone after the wood was soaked in it. The 2-ounce bottle in the back-center of picture 8 contains the petroleum-based oil residue that remained after the acetone fully evaporated. A significant amount of oil was also removed through the repetitive process of steaming and sanding. In the left-foreground of picture 8 are particles from sanding oil-damaged walnut and in the right-foreground particles from sanding undamaged walnut.

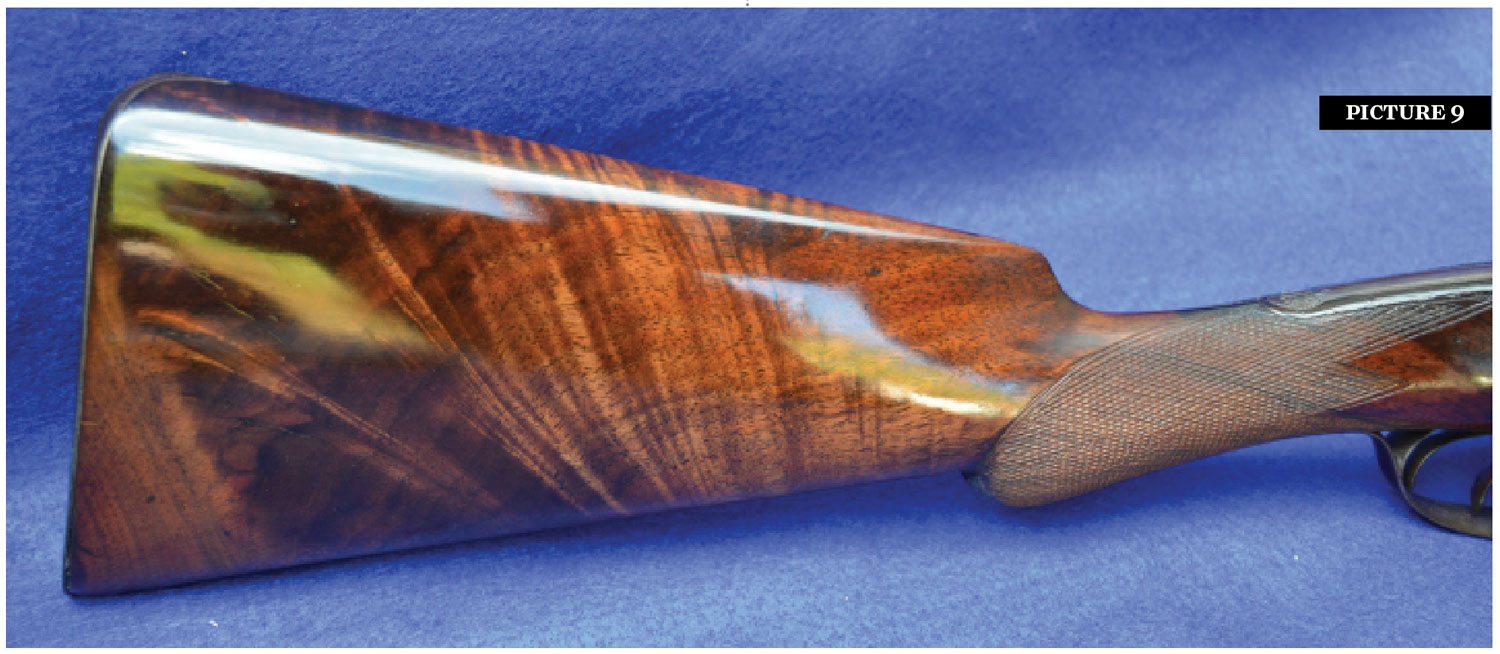

The stock as reconditioned is shown above in picture 9. If left untreated, another decade in the closet or half a dozen boxes of 10-gauge shells on the range could have resulted in major structural damage. This would have been a real loss, as it is the second oldest Nichols & Lefever I know to have survived.

The likelihood of oil-induced structural damage is visually estimated in many cases. Excessively dark wood in the wrist and stock head, especially if accompanied by chips or gouges, are red flags. If signs of old repairs covered by a heavy lacquer finish are present, the prognosis becomes really bad.

The stock of the Parker Quality 2 Top-Action 12-gauge hammergun shown above in picture 10 is one such example. Once the old lacquer finish was removed, a significant crack became visible but the full extent of the damage was only revealed after acetone dissolved the epoxy temporarily holding the wood together. This stock could not be saved. Because Parker sold a large number of this model in 12 gauge, it was possible to find for the owner a structurally-sound replacement stock from a similar gun at a reasonable cost. For sub-caliber or higher-grade guns, however, replacement stocks can be hard to find and expensive.

Sometimes oil-induced structural damage is well hidden. The strength and cohesion of the wood in the wrist of the Greener hammergun in picture 11 were incrementally destroyed over decades from the inside out. It snapped while being shot. This is the most revealing example I have seen of the power of petroleum-based oil to destroy the tensile strength of wood fiber.

In this case, the principle cause of the break was a very old repair of a partial crack on the underside of the wrist that had been epoxied but not pinned. At some point, recoil and other stresses accompanying normal use opened a gap, which allowed oil to flow from the tang and trigger plate into the center of the wrist via the rear tang screw. This gun was obviously valued by the owner and well cared for. But incremental damage of this type is not visible externally. If it is to be discovered and repaired before catastrophic failure, it will be through the complete disassembly and inspection that is part of periodic servicing. When a high-quality gun has to be restocked, it is costly and the nature of the gun changes somewhat.

Stocks with severe structural damage can sometimes be saved, but the repairs can be expensive. Petroleum-based oil destroyed the stock head of the Colt Model 1878 hammergun despicted in pictures 12 and 13. It also caused a deep crack running horizontally through the wrist. The owner wanted to retain as much of the original stock as possible, despite the high cost of doing so. The stock was repaired by removing the entire head stock and half of the wrist, grafting on new walnut, shaping the new wood and inletting for all the metal, refinishing the entire stock and cutting new checkering.

The best outcomes result from catching the oil damage early, when it still can be repaired at low cost. This is where periodic servicing comes in. From the outside, the stock head of the L.C. Smith Model F hammergun shown below in picture 14 does not look too bad. The extent of the petroleum-based oil damage was only uncovered as the result of servicing the gun. Had the damage not been identified and addressed, major structural failure would have been inevitable. However, at this stage, the repairs, which involved removing the damaged wood between the top and bottom prongs and grafting in a new piece of walnut, were not expensive.

In conclusion, antique and vintage shotguns, like other fine machines, need periodic servicing if they are to function properly over long periods of time. The alternative to preventive maintenance is breakdown maintenance, which is more suited to things we use up and replace than to things we value and want to preserve. The interval between periodic services is certainly open to debate, but common sense suggests that if a late 19th or early 20th century gun has not been serviced in a generation, or if there are signs of trouble, the gun is probably due.

The threat to antique and vintage guns from accumulated petroleum-based oil in their wood is real. Recognize the symptoms of this malady, the likely results of not treating it and ways it can be treated. Reconditioning stocks is not part of routine servicing. When a stock should be reconditioned or replaced is complicated. It is best decided by the owner with advice from his or her gunsmith after a gun has been disassembled, cleaned and inspected. Pictures along with written results of the technical inspection help to ensure that the owner’s decision is well-informed.

My general recommendation to owners is to do what is necessary to prevent additional damage, to ensure safe use and to preserve the gun for another generation. But there can also be good reasons to go beyond this, especially if the gun is a reminder of someone or some event. Paraphrasing a comment by one owner about his grandfather’s gun, “something that triggers good memories should be as nice as the memories themselves.”