We had just turned the horses into the wind when I noticed Beck, one of Jeff’s A-Team setters, getting birdy. Was it another bunch of meadowlarks or something better? Then, 50 yards in front of us, Beck locked down tight and Bandit, his canine partner from the A-Team, froze in honor of his point. Jon and I reigned in the horses and slid to the ground, quickly pulling our shotguns from their scabbards. As we approached the dogs, I hoped we were about to find the prairie chickens we had come so far to hunt and not more of the pheasants and sharptails we’d already flushed.

The storied grouse of the Great Plains had been on my bucket list for several decades. A friend in Kansas with whom I hunted pheasants in the early ’80s invited me to come back for a try at prairie grouse. I fully intended to make the trip, but the years slipped by with me busy hunting in 69 other countries and writing several books. The farmers were also busy in my friend’s part of Kansas, turning native grasslands into agricultural crops, which resulted in a precipitous decline in grouse numbers.

Prairie chicken, or pinnated grouse painted by Alexander Wilson in 1811.

The prairie chicken was once as iconic an American gamebird as the bobwhite quail is to hunters in the Deep South. The grouse evolved along with the bison on the mixed-grass prairies of the Great Plains. The buffalo kept the grass short and their droppings provided an array of insects for the chickens.

Before market hunting was outlawed in 1918, millions of prairie chickens were shipped to the markets back east. The birds were able to rebound, but the rapid spread of agriculture along with over-grazing dealt the chickens a serious blow.

Prairie chickens feed on berries, grasses and insects and will readily fly to adjacent grainfields, but always return to the grasslands where they can rest, breed and nest.

The birds rely on their keen eyesight to escape hawks and coyotes, their primary predators, and the short-grass prairie is ideal for this defense mechanism.

At one time, North America had four subspecies of prairie chickens or pinnated grouse (Tympanuchus cupido). Now there are only three.

The heath hen, or eastern pinnated grouse, has been extinct since 1932. It ranged along the East Coast from Massachusetts to Maryland and west to Tennessee. The last of their kind lived on Martha’s Vineyard. Legendary bird artist Alexander Wilson published a painting of the pinnated grouse in 1811. It was probably the heath hen, though they all look alike.

The Attwater prairie chicken lives along the coast of Texas and inland to Colorado. It is endangered and is protected.

The lesser prairie chicken can be found in the arid grasslands from southeastern Colorado to Kansas, Oklahoma and eastern New Mexico.

The last subspecies is the greater prairie chicken, which has disappeared from much of its former range in Missouri, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois. Although the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, IUCN, lists the grouse as “vulnerable,” there are still healthy and huntable populations in South Dakota, Nebraska and Kansas where altogether they number 465,000 birds.

At age 77, I also consider myself a vulnerable specimen. So it was past time for me to experience this iconic hunting adventure on the Great Plains of the Old West.

Jeff Gillaspie loads a horse on the trailer as the hunters get ready to move to another location on the sprawling South Dakota prairie.

I called Chuck Wechsler, my long-time friend at Sporting Classics, and he recommended Bob Tinker of Tinker Kennels of Pierre, South Dakota. Turns out Tinker Kennels had just been bought out by Jeff and Teresa Gillaspie. Jeff worked for Tinker for several years and wanted to keep the outfit going.

After my first phone conservation with Jeff, I knew that I wanted to hunt with him because of his easy-going demeanor and love for the birds and gundogs. My only surprise was that we would be hunting on horseback. I had spent much of my youth on the back of a horse so the idea didn’t bother me much, though it had been many years since I’d been in the saddle.

I was preparing for an early October duck hunt on the flats of Lake St. Claire as a guest of my good friend, Jon Deeter who with Gary Guyette, owns the oldest decoy auction firm in the country. As reciprocal payback, I invited Jon to meet me in Pierre and he quickly accepted.

The hunters remount their horses after a successful point.

South Dakota’s hunting season for chickens and sharpies opens the third weekend in September and runs into the first week of January. Jeff had the third week in October open so we settled on a three-day period, which is the typical time frame for Jeff’s hunts.

Jeff put us up in the Hitching Horse Inn, a 1907 colonial that had been completely restored. It was a great lodge, complete with large bedrooms and private baths, and a hearty breakfast each morning. Located in the center of Pierre, it was convenient to the airport and everything in town.

Jeff leases more than 50,000 acres of grasslands that are only 15 minutes to an hour out of Pierre. Each morning he would pick us up after breakfast and we would proceed to a new hunting area.

So there we were, hoping to make our first debut with a covey flush of chickens. But first blood it was not to be. Seven of the sharp-eyed grouse saw us coming and flushed before we reached shooting range. The birds caught the ever-present wind and rocketed away over a distant ridge. In some of the countryside where we hunted, there were cottonwood trees embracing streambeds, but in most places, there was nothing but magnificent grasslands as far as the eye could see. The topography was gently rolling hills with occasional series of breaks, which the horses handled well. The grouse were widely scattered and we covered around 12 to 15 miles a day. This is why the horses are a necessary part of the hunt.

The author approaches a covey of grouse behind two frozen English setters.

You could tell that Elvis, a gray, and Maverick, a brown and white paint, had done this gig many times. They followed along step-by-step with Bo, Jeff’s stylish, high-stepping Tennessee Walker. My ride proved very relaxing, like sitting in a rocking chair. Within five minutes of the first day in the saddle, one is completely at peace with the horse and the prairie. Mesmerized by the silent beauty of the centuries-old grassland, my first thought was: Why did I wait so long to experience this?

Jeff said that he has quite a few couples who come for the hunt, even though the spouse may not shoot. The non-hunters come just for the experience of riding across the vast prairie and being with a companion who enjoys the sport. He also has many repeat clients each year, which speaks well for the experience.

And let us not forget the most important ingredient to prairie grouse hunting: the dogs. Jeff typically carried eight to ten dogs in his long horse trailer, which had individual kennels built into a front compartment.

His English setters were probably the best I’ve ever seen. One can always recognize the love between a man and his dogs, and it was evident here. He spoke to them calmly, yet they would respond instantly. Just a word from Jeff could turn the dogs and head them in a different direction.

Most of the grass stood six to eight inches high, but occasionally we’d find a stretch of tall grass where the birds would hold better. We would swing the horses around and approach this taller grass into the wind. The dogs, meanwhile, would cast a hundred yards off to the left side and then swing back to cover the right side.

It was quite warm, the temperature climbing to 70 degrees by mid-afternoon. The dogs would come to Jeff when they needed water and jump up on the side of the horse where they drank from a gallon jug.

An exuberant Jon Deeter with a fine brace of chickens.

If the dogs approached too close to a field of corn or sunflowers, Jeff would call them back. There could be chickens in the field, but more likely a bunch of ringnecks and we didn’t want to waste time climbing down on pointed pheasants.

The pheasant season was opening the Saturday we were leaving and the entire city of Pierre was booked with out-of-town hunters. Jeff also offers combination hunts—horseback for prairie grouse in the morning and walking for pheasants in the afternoon.

Jeff would usually park his horse trailer in the center of the hunting area. We would cover a portion of the ground by mid-morning, then return for a drink and a change of dogs. We would return to the trailer again for lunch, which was always a hot meal cooked by Jeff on a gas grill.

After lunch, we mounted up and worked our way across the grasslands to some old alfalfa fields. Close to the corner of the field, setters Duke and Bell froze at the same time in a picture point. Jon and I dismounted, quickly giving the reins to Jeff and proceeded forward to the dogs. We had yet to fire a shot at chickens and I hoped this would be the moment of truth.

Duke began inching forward and I was afraid the birds were running. Jeff shouted for us to move ahead quickly and we hurried past the dogs. Suddenly a prairie chicken exploded 20 yards in front of Jon and he dropped it in a cloud of feathers. We were both walking to where the bird fell when another flushed 30 yards in front. We fired simultaneously, grounding it easily.

At our shots, four more chickens flushed out of range and were last seen gliding over a distant ridge. Prairie grouse can fly as fast as ruffed grouse, though they typically go straight away, giving the shooter enough time to get on it and shoot.

We were very excited now as we had our first chickens so we took some time to admire the birds. Both sexes are medium-size grouse, stocky with round wings. They have short tails and the adult males have orange comb-like feathers over their eyes. They have a circular, un-feathered orange neck patch, which they inflate when displaying on their breeding grounds in the spring. The breasts of both birds were laced with rows of black-and-white bars.

As I sat there admiring this iconic gamebird of the Great Plains, I thought about that Alexander Wilson painting hanging in my library back home in Georgia. I’d enjoyed the watercolor for at least 40 years before I finally held the real bird in my hand. I was excited and appreciative for the opportunity.

A grouse hunt with Jeff’s Tinker Kennels is about the whole experience: the dogs, the horses, the beautiful prairie stretching to the horizon and, of course, these wonderful gamebirds. Today, this part of the Dakota prairie looks much as it did 180 years ago when the buffalo and prairie chicken existed side-by-side on these great American grasslands.

But enough of this daydreaming. We had their number now. The pressure was off and there were fresh dogs to release. We had two days left and plenty of shells. Even Elvis looked at me and shook his bridle as if to say, “Let’s go boss.”

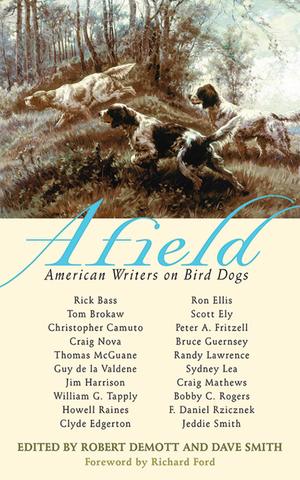

This marvelous collection features stories from some of America’s finest and most respected writers about every outdoorsman’s favorite and most loyal hunting partner: his dog. For the first time, the stories of acclaimed writers such as Richard Ford, Tom Brokaw, Howell Raines, Rick Bass, Sydney Lea, Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Phil Caputo, and Chris Camuto, come together in one collection. Shop Now

This marvelous collection features stories from some of America’s finest and most respected writers about every outdoorsman’s favorite and most loyal hunting partner: his dog. For the first time, the stories of acclaimed writers such as Richard Ford, Tom Brokaw, Howell Raines, Rick Bass, Sydney Lea, Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Phil Caputo, and Chris Camuto, come together in one collection. Shop Now