Scene: A summer morning, Florida Keys, late July — but the events outlined here could have transpired in August, even September, just as well.

We load the cooler with gallons of Gatorade, water and ice, with the reasonable expectation that it will feel downright tropical on the flats. No higher mercury readings than May — well, maybe four or five degrees — but the gentler winds of summer boost the power of dehydration to wilt away human resolve. We’ll need, and take, whatever advantages we can muster, and count on adequate fluids to help sustain us. Then, sunscreen, with rods loaded and eyes polarized, we roar the skiff toward A Certain Place. Mangrove blossom wind buffets the hollows of our ears as we skim across water like tourmaline silk.

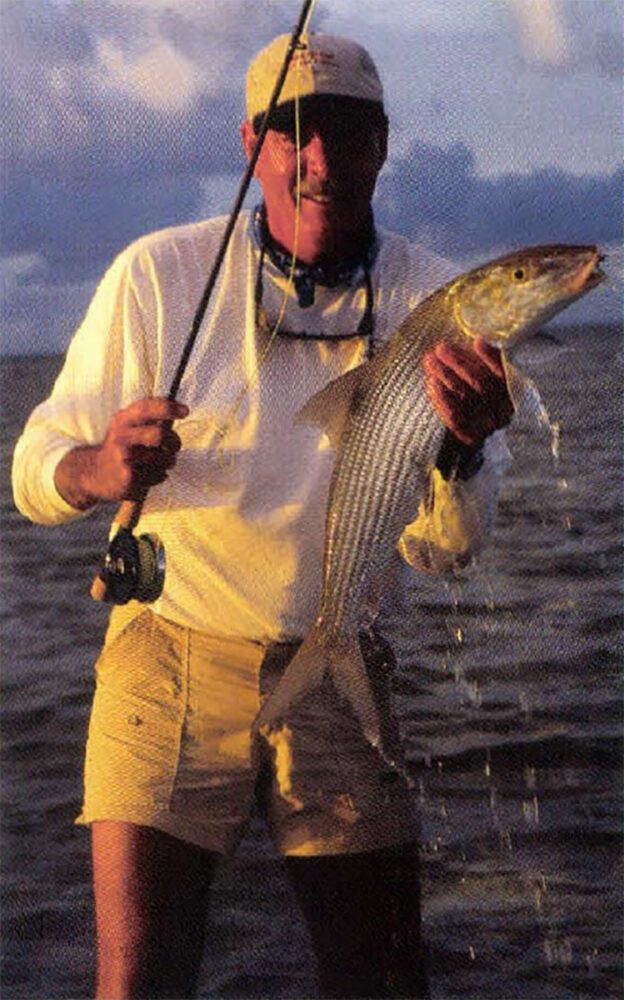

Bob with a big Keys bonefish.

As they always seem to do in their prescient way, the tarpon roll upon us before we get set: push pole halfway unhooked, rod just clearing the rack, camera still in its case. Silent, the fish arch through the shallow water en route to their secret procreation appointments. An occasional whoosh of air from their primitive lungs comes out softer than, but similar to, the puff of bottlenose dolphin. Our eyes go round and hearts hit pause. Possibilities swell.

“Here they come!” Our buddy Duane Baker blurts.

Bob strips out line, jerkily fast in his rush and eagerness. I snick the lens cap from the camera, find a vantage in the scramble, find focus.

Bob casts. Strips. Swears. He casts again. The tarpon slide away, out of our lives. Duane mutters. I feel tightness in my shoulders. Momentary disappointment floods across our thoughts. A brief minus tide. But morning sun still gilds the flat like hammered gold over cyan; plenty of time for other tarpon to advance, to entertain us.

Popping back into action, Bob gasps, “They’re coming back!” Again the tarpon have gone around tour expectations, done what they intended instead. Rather than continue along the coastline they have circled us, lazily. To see what these boat creatures are doing? To play, take another chance? Can they sense our excitement, share in it somehow?

“Take the shot!” Duane insists.

Bob fires one out. I hold the camera focus tight on the end of the flyline, hoping to capture the flash of silver as it boils upward, hooked and indignant, a sword of beauty and surprise.

From the corner of my eye I see Bob’s arm yank, yank, hear Duane whoop exultantly from the poling platform. I dare not breathe, or move. Then pow out of the water, straight up, as if a lateral direction would never state the case quite so defiantly, bolts the target of my lens. Snap, whirr. Splash, down, a crashing hole in the water forms eddys. And Bob’s reel sings out happiness and he laughs wildly and Duane yells, “All right!” And I, too, have begun odd burblings, and my eyes leak tears as I search for where the tarpon may erupt again.

“He’s coming up.” Snap, whirr.

Put the wood to him!”

And, finally, a breathless tussle later, “Can you grab the leader?”

Silver bullet.

We revel a moment in that ocean herbal freshness tarpon give off, of mullet breath and seaweed sauce. Then we release him and quench our parched throats. A distant sailboat takes its triangle slowly along the horizon. On this flat, as far as we can see up and down the coast, we float alone with the egg yolk sun and the white, cheeping terns and all these fish.

Guess you’d better catch a permit now,” Duane says.

“You take a turn,” Bob smiles back. On “play” days (which actually constitute research and continuing education) with two guides on the skiff, shots at fish and pushpole duty are traded off.

“Naw, it’s early. You could Slam.” His emphasis reveals the reverence flats fishers have for the feat of catching a tarpon, bonefish and permit all in the same day.

We shift the position of the skiff slightly, to a different edge. Shift our focus as well, to discriminate between illusion and reality. Like when watching football, it helps to know what you’re looking at. More than just a change of perceptual set, to see a permit, or just to try, presents a real challenge to the limits of human vision.

“What’s that?” Bob x-rays into a point of sea.

“Fish,” Duane quips, in no way facetious. From a distance, permit have the remarkable ability to appear like bonefish, tarpon, barracuda, even sharks. This talent has me convinced these moon discs affect more than that which meets the eye, to exercise a shopworn term, because what meets the eye often looks just like, well, something Else.

“Permit?” Bob rhetorically asks the world in general, assured that we share his bafflement.

“Maybe. Maybe more tarpon.”

“No! No! I saw a flash!”

My heartbeat achieves close to the same rate as when pumping my bike against the force of a 20-knot wind. Passive aerobics, permit style. I stretch and peer at the water, hoping for a photograph, a memento, a keepsake of charisma. Which I rarely obtain until one of the pouty fish is tugged close to the boat.

Bob casts, a long one, with a body-english grunt.

I fidget, no way to influence the outcome here, and consider images, both photographic and captured by the optic nerve. The plain magic of a pinhole camera; how the shapes that appear before us are touching us in away — via photons, I suppose. At the risk of sounding as if I’ve been sleeping under the microwave too long, it peels layers off what might blithely be referred to as sanity to think how these fish, these Permit, somehow manage to project, reflect, display, contours they don’t possess.

“Unnnhhh!” Bob informs.

“Hey! You got him!”

I revert to attention, watching the brave and the determined attempt to out-pull each other. Silver, sideways, roles reversing, the finale a satin-coated treasure in the hammock of Bob’s forearms. Snap, whirr.

“You’re gonna do it, man!” Duane says, confident now that the two harder fish of the Big Three (in the estimation of many anglers) have come to the boat. “Let’s get after the bonefish!”

Hooking a tarpon on a fly is one thing; landing one of these silver rockets is quite another.

Bob’s face glows, caught up in the thrill. Oh sure, he has landed each of these glitterati of the saltwater flats individually, and loves the rush, always. But seldom does he enjoy the opportunity to bag all three on the same outing. Other times when this possibility becomes likely, he’s pushing his clients into the light position so they can score.

“I’ve got another shot or two left, I think.” I’ve blown film on that Holy Grail of those left: holding the camera — the often futile guest for the perfect shot of a jumping tarpon. But a frame or two remains. I hope to fill it with at least a bonefish “grin and grab.”

Duane pushes across acres of flat. The tide has left it barely damp, and bonefish wakes lead us wobbling after them, tails here, trails there. Bob casts to a pair of bones, their caudal fins twinkling in the slant of afternoon light. The fly sets down nicely and I think, “that deserves a fish,” but the bones, bless their unpredictable precious metal hearts, think otherwise. They scoot.

“I suck!” Bob moans.

“No man, that was perfect. Here’s some more, 2 o’clock, out pretty far.”

Bob tangles his line for a moment, succumbing to the same buck fever that plagues all who love the sport. “Look at this,” he laughs and curses and de-webs himself, “I’m choking like a rookie.”

Then he remembers to relax, that these are just bonefish, after all, and he’s caught them by the hundreds, so why should today be any different? Well, Herr Tarpon and Senor Permit have added a dollop of intensity, of course. The quarry at hand toodles along in the turtle grass, pretending or maybe actually oblivious to our combined beam of attention riveted to their every movement. They sparkle their tails out again, rooting happily. Bob plants his feet and drops the little Clouser minnow near them. Taunts, hops, hopes.

I’ve quit breathing again, just in case respiration might affect the outcome or the bones might hear me exhale. I’m afraid to hope, like when you desire something but fear if you want it too much you’ll jinx yourself. And if I feel this superstitious, no wonder Bob’s getting tweaky. I suppose, a hundred years down the road it won’t matter whether or not he gets this Grand Slam. Maybe it’s good now and then to step back into perspective land, just to keep all this meaning and mystery in balance. But then if nothing matters, why doit, and you can philosophize yourself light into a near-nihilist corner of apathy going too far that way. Right now, it matters a whole hell of a lot. Why, the future of the whole planet may depend on the touch of this bonefish.

“Yessssss.”

I’m not sure if Bob’s voice or his sibilant reel pulls my eyes up to the fly line, disappearing along with the retreating bonefish — its tiny organic motorboat of awake, Duane’s nervous chuckle, my stiff neck.

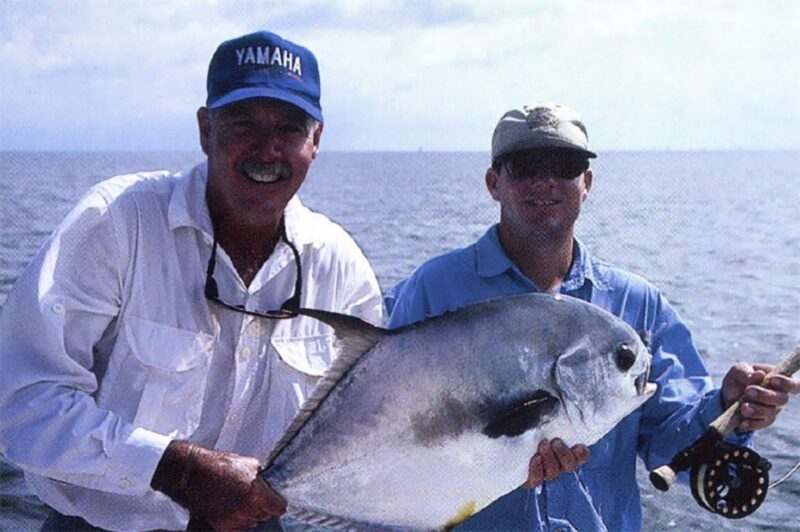

Bob displays a permit caught with the help of fellow guide Capt. Duane Baker.

Bonefishing is a matter of inches, Bob always insists, meaning the finesse required in the delivery of the fly to the target, but reeling in a bonefish is a matter of yards. Often, hundreds of them. And while I wait for the fish to be winched closer for a portrait, the reel cranks, then zings, then cranks, and Bob mutters things like, “Come on fish, don’t wear yourself out.”

Finally, the bone fish makes his argent appearance, and we gloat and laugh and carefully hold him for his moment of fame before releasing him to safety.

With afternoon light this rich, the sun mango yellow, the sky hosting puffy bolls of vapor, some bruised with wetness, it’ll be a great shot, I think. Click, whirr, beep, beep, beep. Last frame, out of film. Did it take? We decide not to care. The essence of this moment is part of us now. That’s enough.

Though late fall and winter in the Keys qualify as soft duty compared to the rigors of the North, cold fronts swoop and droop across Florida’s peninsula occasionally. Gets into the 60s (imagine!) at times, which definitely causes the bonefish to hold their pectorals tight to their sides. That’s when U.S. 1, our only road, clogs with the out-of-state license plates of sunseekers and cabin-fevered fly-fishermen eager to try their luck on the flats.

Spring continues the busy season. Even though the snowbirds return home, rabid tarpon fishermen take their place. The flats teem with skiffs and guides and anglers and those admirable, man-sized fish. It’s an event, a spectacle. And when you hook up to one of the regal Megalops atlanticus, all external distractions fade into the uphill battle you’ve initiated.

Ah, but Summer. Comes July and most of the tarpon fishermen head off for spring creeks and mountain lakes. Hotel rates drop. The guides get their chance to stretch, fishing virtually deserted flats for The Big Three. Just because you tear off the calendar page labeled June doesn’t mean the fish go away.

Tarpon Crab, tied by Bob Rodgers.

The adult tarpon continue to migrate through the waters of the Keys through August, and junior tarpon roil the waters of Florida Bay all fall until cold fronts spoil their party. The slick calm days are perfect for spotting permit on the flats, and bonefish can always be found. I admit to sizable qualms about revealing the intoxicating solitude of our flats, July through October. Those months restore a sense of yesteryear, how it must have felt before many of us arrived. So while Homer and Marge, along with most everyone else east of the Mississippi, stand in endless lines at Disney World, some lucky anglers are visiting the Keys to work on their Grand Slams. And a few earn them.

Oh yeah, that last shot, of the bonefish? Half a frame.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2004 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

In Fly-Fishing Knots and Connections, legendary fly fisherman Lefty Kreh tells anglers everything they need to know about what may be the most crucial aspect of successful angling-the connections between the reel, backing, fly line, leader, and tippet. Lefty’s years of painstaking research and testing pay off with hard and fast rules. Buy Now

In Fly-Fishing Knots and Connections, legendary fly fisherman Lefty Kreh tells anglers everything they need to know about what may be the most crucial aspect of successful angling-the connections between the reel, backing, fly line, leader, and tippet. Lefty’s years of painstaking research and testing pay off with hard and fast rules. Buy Now