“I live in cities now and travel the world but I keep coming back to this prairie because I know this is where I belong.”

Even at his busiest sitting at the anchor’s desk of NBC News for more than 20 years—longer than Walter Cronkite at CBS—Tom Brokaw managed annual pilgrimages to South Dakota to remind his Labs why he was feeding them in his Manhattan studio the other 11 months a year. The state draws him back most autumns for what he describes as a religious holiday in these parts, a pastime most who grew up here celebrate come October. Welcome to pheasant hunting central, a bird and a state whose brands have become synonymous.

Much of South Dakota is a pheasant pasture owing to an ideal mix of grasslands, food crops and shelter belts that sustain and protect the birds throughout the state’s seasonal weather extremes. There are, however, a handful of places where the bird transcends the wingshooting lifestyle. One such destination is the 5,000-acre Paul Nelson Farm, an understated phone book name for a retreat that was created on a passion for pheasant hunting. This isn’t one of those quaint lodges for six or eight guns at time, but rather is closer to the Taj Mahal of featherdom.

The sprawling lodge compound at the Paul Nelson Farm. The venue, if the Orvis-endorsed lodge awards are any indication, is widely regarded as one of the world’s best bird hunting destinations.

Throughout the expansive, two-story campus, there are cigar lounges, private bars, poker tables and giant television screens that make the place one enormous and opulent man cave. Everywhere you look there are reminders of the birds—mounts, paintings and photographs—along with all manner of South Dakota artifacts from bison skulls to ancient native tools. A nearby jet strip makes it easy for the corporate set to arrive, do deals while toting a shotgun through thousands of acres of idyllic pheasant cover and return easily to their home ports. During the Bush-Cheney years, the Vice President was a frequent visitor, famously shutting down the air space around the capital of Pierre as Air Force Two arrived for the pheasant opener, the unofficial New Year on the Dakota calendar.

This scene is repeated more than a million times across South Dakota each autumn as more than 100,000 pheasant hunters take to the fields to pursue the Chinese imports.

Pheasants have effectively become a form of currency in South Dakota, luring more than 100,000 non-resident hunters from across the globe each autumn to don blaze and march lock-step through the cornfields, grasslands and shelter belts. The birds are now such a part of the fabric of the state that it’s hard to imagine this landscape without them. The first successful introduction of pheasants in the United States dates back to the late 1800s in the Willamette Valley of Oregon. Thanks to the efforts of the conservation group Pheasants Forever and others, the birds are now flourishing across much of the Midwest and beyond. Pheasant hunters now contribute nearly $300 million annually to South Dakota’s economy as they harvest some 1.2 million of the state’s estimated 9 million pheasants.

As we begin to hike a long row of millet, a rooster erupts from Brokaw’s right, quartering to the left. He folds the bird in what amounts to a reflex, just like countless others he’s taken since his youth in the state. He pumps his fist and smiles in celebration, an affirmation that while the years may have taken a step or two, there’s still plenty of punch left in the South Dakota kid.

“When I come out here and do this I feel like I’m 15 years old again,” he says. “I’m connected to this prairie in a way that I didn’t anticipate I would be when I left 50 years ago. I live in cities now and travel the world but I keep coming back here because I know this is where I belong.”

Being on the front lines of history for much of his adult life, he covered—sometimes lived—every major global story for more than two decades, including famously being the only anchor in Berlin for the fall of the wall and, ostensibly, the collapse of the Soviet empire. Before the proliferation and noise of cable news, there were only three broadcast networks. With that came large audiences and the gravity of being invited into many of America’s living rooms each night to sometimes deliver news that he knew would change the world forever. In times of war and peace, crisis and tragedy, he was the man to whom millions of Americans turned to hear it straight—good or bad.

Also joining us on this hunt are some guys named John Thune and Jeff Crane. That would be U.S. Senator Thune, the pride of Murdo, South Dakota, population 482. Crane runs the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, a hunting-fishing advocacy group that works on the Hill as well as at state houses nationwide. Thune looks like he’s out of central casting, tall, handsome and well mannered. He’s the type of polite and kind soul that the good people of South Dakota produce. He is, in a word, representative. Spend time talking with him, however, and it’s hard to picture his gentle demeanor enduring the swamps of Washington, but like others before him, he’s learned to separate reality from Washington.

Of all the states where ringnecks thrive, only South Dakota has embraced pheasants and pheasant hunting in such a way to own the undisputed label of pheasant capital. Great lodges are scattered throughout the state, each offering their own take on the pheasant hunting experience which has reinforced South Dakota as the pheasant hunter’s destination of choice.

What you often get in South Dakota that you don’t see with the same regularity in other states with ringnecks is the spectacle of hundreds of birds airborne at once. As a line of guns pushes through cover, the theater of an avalanche of birds cascading out of habitat with a cacophony of pheasant cackles is the kind of take-your-breath-away embarrassment of riches that reminds you that the Dakota prairie is where any bird hunter wants to be come October.

“Get ready, Red’s got one here,” says Brokaw as his Lab works pheasant scent. As the Senator and I ease up, Brokaw advances and flushes one rooster which initiates a chain reaction of perhaps a dozen more birds flushing from nearby cover, launching randomly like feathered missiles. We make the most of the opportunities, sending enough roosters to earth to keep Red and the other Labs in the group busy for several minutes.

As we return to the lodge, I ask Brokaw about life as a hunter in Gotham, “My New York friends sometimes ask me if I hunt,” he says with a wry smile. “I tell them that I do and I love it. We eat what we kill and it’s been a part of my life and has been a part of this country for a long time. It’s great for the economy and for conservation. It’s a win-win.”

Combine world class wingshooting with fine dining – including prime rib night – and you have the Paul Nelson Farm near Gettysburg, South Dakota. The lodge has become a favorite among executives looking for a board room escape while still conducting business.

After our day of pheasant chasing we have worked up an appetite and, as luck would have it, prime rib is on the menu, which means it’s time to loosen the belts and prepare to founder. Erik and Paul tend to the carving station to slice a slab of beef the size of a small calf, whatever temperature that suits your taste. In the corner of the dining room is Paul’s wife, Cheryl, strumming a harp. It all begs the questions, where am I and how do I make sure that I never have to leave?

If there’s anything that Brokaw has failed at in his life it’s retirement. Not even a multiple myeloma diagnosis, a form of incurable but treatable bone cancer, could slow him down. While that news altered the course of his life, it led him to write a book about his health experiences which, in turn, helped others going through similar challenges. Now, thanks to advancements in the treatment of that cancer, there isn’t much interruption in the life of Tom Brokaw. He continues to add to a resume that has no more room, currently working on a book about his father, while making sure his new Lab, Doc, is just as spoiled as his predecessors.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow Sporting Classics TV host Chris Dorsey at Forbes.

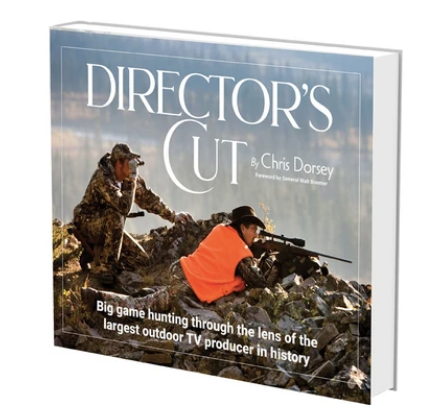

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

Dorsey has spent the past 25 years investigating and chronicling the animals, people and unforgettable places home to remarkable big game hunts while producing nearly 60 outdoor adventure television series. In the process, his teams amassed a library of more than 100,000 hours of HD footage and nearly 150,000 photographs, making Director’s Cut (the book and DVD) an unmatched celebration of the world of big game hunting. Pre-Order Now