Peter Gray and Peter Stewart, two painters living in South Africa, inhabit different corners of the Cape region and chronologically are a generation apart. But each welcomes the direction that contemporary wildlife art is taking.

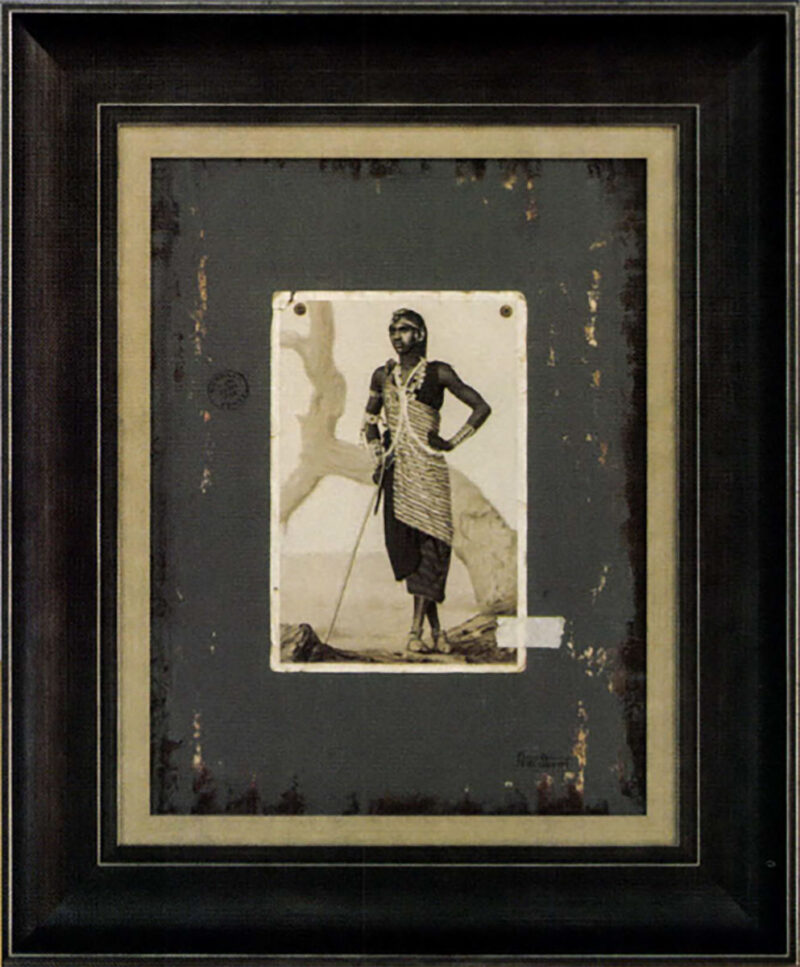

Vintage Maasai

In case you haven’t noticed, these are fascinating times to be an outdoors person and a collector of fine sporting art. The style of traditional painting that long excited our elders just doesn’t command the same level of appeal among younger people coming of age and possessing different sensibilities. Those who ignore this trend do so at their own peril. Peter Gray and Peter Stewart, two painters living in South Africa, inhabit different corners of the Cape region and chronologically are a generation apart. But each welcomes the direction that contemporary wildlife art is taking. To those who crave dramatic portrayals of African big game set inside of majestic landscapes, Gray and Stewart still deliver the goods. Their scenes of charging elephant scenes, portraits of leopards draped over baobab boughs and lions engaged in stalking prey will give you heart palpitations. Yet their other interpretations of the wild bushveld are pushing the envelope, showing that wildlife art in the 21st century need not be held hostage to the same kind of representation that preceded it.

”Young people aren’t growing up with the same kind of orientation many of us did-those of us in North America or Africa who either grew up in our versions of the bush or spent long periods of time out in it where it forged our identity,” says Zimbawean-American Ross Parker. “Peter and Peter are products of that, but their fine art aesthetic has wider appeal, especially among our growing urban audience.”

Zebra Panic

Parker who operates Call of Africa’s Native Visions Galleries in Jupiter and Naples, Florida, says Gray and Stewart are enjoying some of their strongest sales among collectors under 50 years old.

“I’m hearing two things,” he says. “The first is that older collectors have filled up their dens and trophy rooms with traditional portrayals of big game animals and their wives want something different on the walls of the living room.”

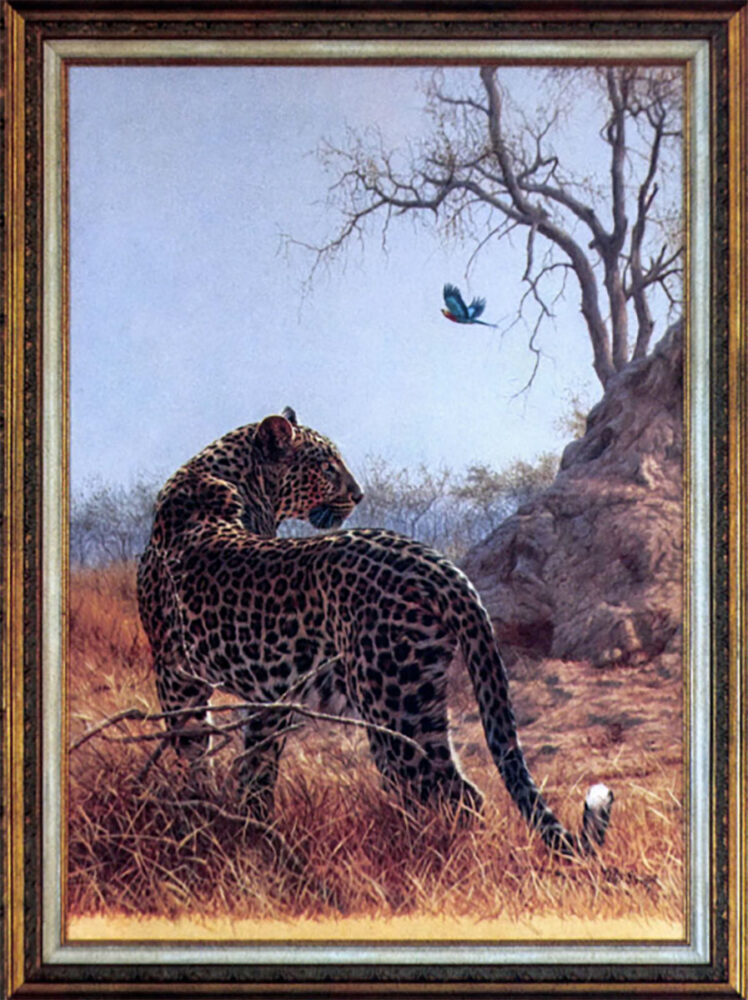

Poised Reflections

Secondly, Parker notes, the grown children of aging collectors aren’t interested in decorating their homes and offices with their parents’ tastes. Couples, typically involving one spouse who hunts and another who doesn’t, want to build contemporary collections together.

I became aware of Gray and Stewart nearly a decade ago during a visit to Gray’s studio in Noordhoek east of Cape Town. Later, while spending a day at painter Kim Donaldson’s home outside of Durban, I was introduced to Stewart. Donaldson, a boundary-pushing painter in his own right, has served as Stewart’s mentor.

Born in 1950, Gray has steadily built a loyal following of collectors in North America, the UK, and Europe. His provocative images, in which he combines species not typically associated with one another in the wild, have been a delight of clitics. Moreover, his elegant avian portraits of waterfowl and marsh birds have routinely been juried into the annual Birds in Art Show at Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wisconsin. They have also been selected for the museum’s prestigious traveling exhibitions.

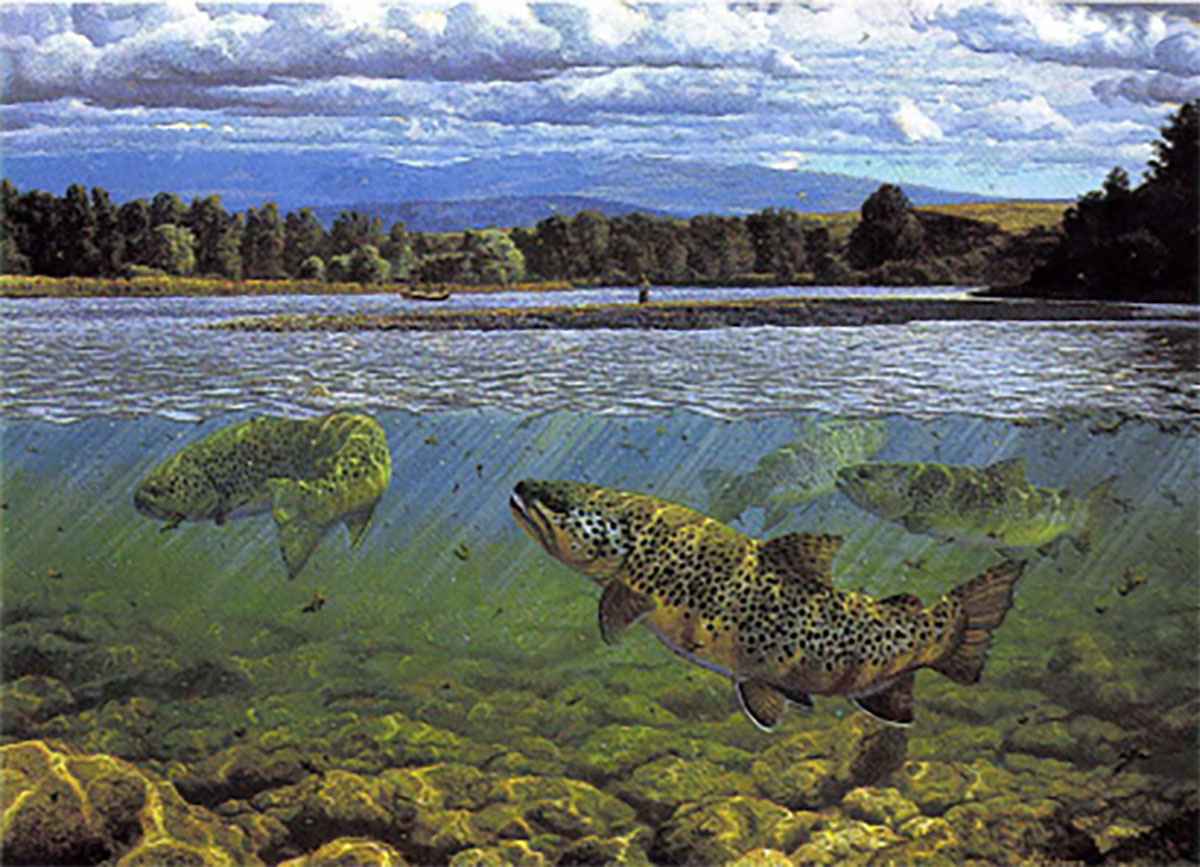

Classical Capture

Kathy Foley, the Woodson’s director, told me a few years ago that Gray’s painterly approach to realism is more kindred to the late Andrew Wyeth than art one would find at a Ducks Unlimited banquet.

As a boy raised in an old colonial farmhouse in the middle of the African bush, Gray says the aesthetics of nature were imprinted on him; so, too, was an archetypal relationship with wildlife.

The Grays lived close to Hwange and Matobo national parks. “Wild animals would regularly come into our garden to eat our vegetables and occasionally my dad would go out to protect the family from some dangerous creature, armed with just a dustbin lid as a shield and broomsticks. That Africa is gone.”

Turned In (bat-eared fox)

Gray knows firsthand about the trauma of disruption_ After attending art school in South Africa, Gray and his wife, Ann, raised their family in Bulawayo where he worked as a fine art jeweler and artist whose forte was landscapes and portraits. During his 20s, his work was already selling at galleries in London.

But following the trouble that began in Zimbabwe with social unrest and corruption that devastated the business climate as well as wildlife preserves, the Grays had to abruptly leave the country. They resettled in a small community just outside of Cape Town. Ironically, it was then that Gray’s reputation as a painter of wildlife started to soar.

“Peter was ahead of the curve, in being true to himself and challenging convention,” Parker notes. “He produced art that was a genuine expression of his own vision that contrasted sharply with the paint-every-feather kind of art that today is out of fashion. He certainly didn’t paint for the market; collectors who were looking for something other than formulaic composition of Africa found him.”

Peter Gray painted this weaver bird clinging to its nest, a common sight to anyone familiar with the African bush.

Gray draws from the entire spectrum of art history, though he is quick to single out a trio of painters.

“From an artistic perspective, I can level it down to three key artists — Francisco Goya, Francis Bacon and Ray Harris-Ching — who have influenced me,” he says, noting that he met Bacon as a young man in London and watched him paint.

”You may not be able to put Goya, Bacon and Ching together in tile same category, but the energy and power that emanates from their work is the same.”

Gray, like his contemporary Donaldson, believes it isn’t enough to be an African artist and not interpret the myriad forces at play threatening the survival of wildlife. He finds fertile ground indeed in the juxtaposition of human culture and values, the clash between untamed landscapes and development, and the relationship between people and nature.

Neighbourhood Watch

For more than a decade, Gray has produced pieces arranged around the ongoing theme, ‘The Nature of the Game.” It is more than a play on words. It has been a platform for exploring the meaning of change, adaptation and survival.

“I liken the art process to that of a pathway leading not necessarily to any particular destination but offering mean other opportunity to explore and experience the life-force that drives and supports all things,” Gray says, noting that his most powerful emotion is humility before the unknown. It’s a pathos that every African, white or black, urban or rural, must learn, for there are no certainties except that in order to endure, one must be aware.

Ellies and Zebra Waterhole

Born in 1966, Peter Stewart grew up in Durban where he developed a deep bond with wild areas in KwaZulu-Natal. His passion for wildlife led him to become a graphic designer for parks in the Natal province, a region famous for rescuing its rhino populations in the 1960s. Those populations have since been devastated by black market poaching.

“It’s not only wildlife that conjures up a nostalgic imagery and iconography of Africa, but also the many tribes, different settlers, legendary explorers, and big game hunters,” Stewart says. “Many of us who have traveled around Africa tend to relate to these early adventurers and their captivating stories.”

Stewart’s foundation is built upon studying the techniques of European masters and artists ranging from Wilhelm Kuhnert to Bob Kuhn, David Shepherd, Paul Bosman, Dino Paravano, Shirley Greene, the late Simon Combes, and others who were traditional in their approaches. Yet it was Donaldson’s mentorship and his multimedia approaches to his subject matter that convinced Stewart to be daring.

All Ablaze

Ivan Carter, the Zimbabwe-born conservationist, professional hunter, and TV show host who spends 200 days a year in the wilderness, is a collector of Stewart’s work.

“The ability to accurately portray wildlife moments is a very rare talent,” says Carter. “Peter’s passion for wildlife shines through in the moods and lighting he conveys.”

Stewart is working on a new series that he calls “Legends of Africa,” in which he portrays people such as explorers David Livingstone, Henry Stanly and Frederick Selous.”

Cool Reflections

Each painting concept begins by creating a background of textured paint, manipulated and stressed to look like an old weathered surface onto which I paint what appears to be a real photograph,” he explains. “I sometimes use old frames, pieces of tape, old nails, postal stamps, studs — all to create an authentic feel that matches the painted ‘sepia’ image.”

The paintings morph and develop the deeper that he progresses into them, and collectors love them because they are so different, so provocative; they command attention on the wall. When pressed to describe them, Stewart says, “I guess you could call them contemporary realism.”

On principal, that is the goal — that the paintings become something more as you study them. That’s the contemporary realist reach.

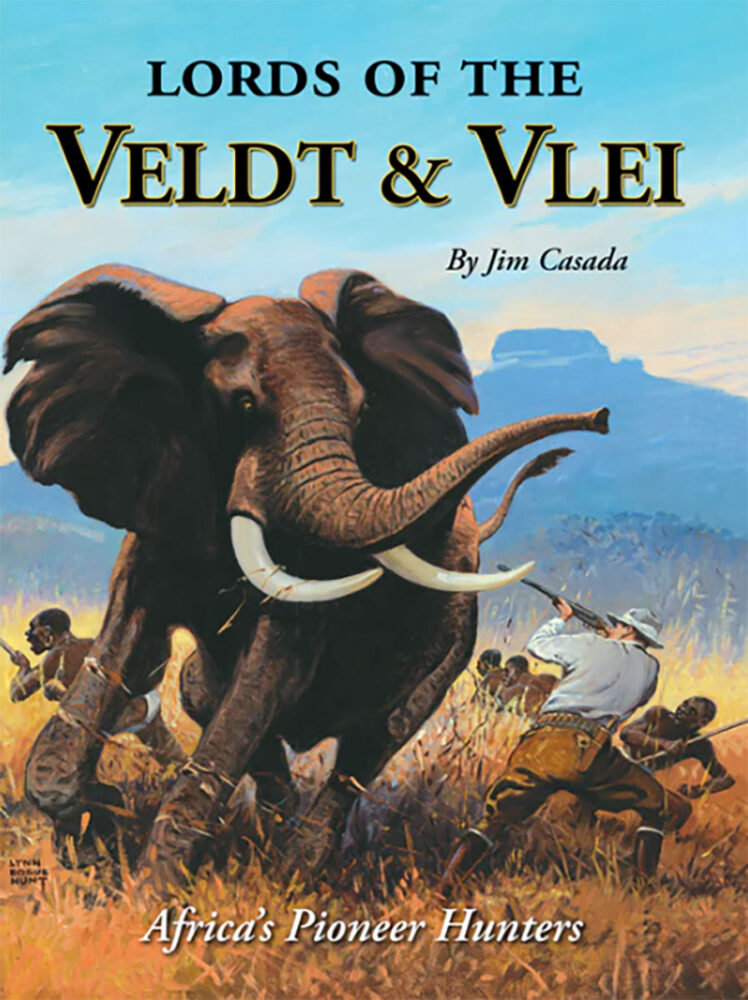

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now