The intriguing survival story of a deer species discovered in China more than 150 years ago.

When I was a small boy I started digging a hole in the backyard. My dad came out and asked me what I was doing.

“Digging a hole,” I answered.

He smiled broadly. “If you keep going, you might go all the way to China,” he said jokingly.

From that time on I was fascinated with this boyhood fantasy, and I always wondered what would happen if I actually succeeded.

Now I know. Had I been able to dig a hole all the way to China, I probably would have ended up in Beijing’s Imperial Hunting Park. To those of us who are deer hunting aficionados, we’ve all heard incredible tales about the amazing tenacity of whitetails and their unbelievable endurance. One term seems to fit our native whitetails to a ‘T’. They are survivors. Perhaps this is why the story behind a distant cousin of the whitetail that comes to us from China is so intriguing.

The roots of this story go back many centuries, and it involves the survival of a species of deer that is alive and well today because of one factor: controlled hunting. Centuries ago, had it not been due to the desire of the Emperor of China (and later others) to hunt this deer, the species would have become as extinct as a T-Rex. It’s just one more example of how properly managed hunting has helped save a wild species.

Believed to have been native only to northeastern and east-central China, this unusual deer was originally named by the Chinese as sze pu shiang (sì bú xiàng). A rough translation means “none of the four.” Possibly dating as far back as 200 A.D., this unique deer was described as “having the neck of a camel, the tail of a donkey, the hooves of a cow and the antlers of a deer.” Its antlers somewhat resemble those of elk or red stags more than they do those of whitetails. But unlike most other members of the deer family, this animal sports a much longer tail.

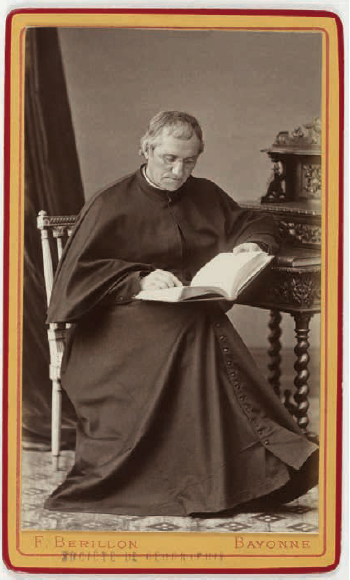

Père David’s deer is named after Père Armand David, a French missionary and Jesuit priest who viewed a herd of the animals in China’s Imperial Hunting Park and later smuggled a skin back to the Museum of d’Histoire Naturelle of Paris.

Later on, a shorter name was given to this deer by the Chinese: milu; by the 1800s it was known in other parts of the world as Père David’s deer.

During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), a small herd of milu were kept by the Chinese Emperor in the Imperial Hunting Park just outside the city then known as Peking (now Beijing). The heavily guarded park was completely isolated from the outside world. In addition to being revered by hunters, these animals became a symbol of good fortune for Chinese royalty. Eating the meat of the milu was believed to enhance the prospects for everlasting life.

In 1865, the year the Civil War ended in America, Père Armand David, a French missionary and Jesuit priest, traveled to Peking on a missionary assignment. Having a deep interest in science and nature, as well as religion, Father David discovered a small herd of very unusual deer thriving in the Imperial Hunting Park (Nan Hai-tsu Park) just outside the city. The park was surrounded by a high wall some 45 miles long, and the small herd of deer was closely guarded by the Emperor’s soldiers.

The outside world knew nothing of this strange deer’s existence until Father David reportedly bribed a guard to let him peak over the wall. Greatly intrigued by the herd of 150 animals, he later acquired the skin of a milu (probably through more bribes) and smuggled it back to France.

A short time later the renowned French zoologist Henry Milne-Edwards wrote a paper about the newly discovered deer species and named it P. davidianus, or “Père David’s deer,” after Father David.

As word of this unusual deer circulated through the scientific community, the Chinese were coaxed into gifting about a dozen specimens to zoos in Paris, London and Berlin. However, none of the deer survived except in one place—England.

In the late 1800s Herbrand Russell, the 11th Duke of Bedford, obtained a dozen Père David’s deer for his private game preserve in Bedfordshire (about 50 miles north of London), where he established a small breeding population in his Woburn Abbey Preserve. While the captive herd thrived in England, things were rapidly changing in China.

In 1894 the Imperial Hunting Park was destroyed by flooding of the Yongding River. Some of the deer drowned, but most escaped to suffer an even worse fate. They were soon killed for food by hungry peasants. Only a few dozen animals survived in the park.

Then in 1900 the handful of deer that had survived the devastating flood were finished off and eaten by starving Chinese countrymen during the Boxer Rebellion. As a result, the entire herd of Père David’s deer that had been so closely protected in the Imperial Hunting Park for some 17 centuries was gone.

Realizing his small herd of Père David’s deer comprised the only remaining members of their species in the world, the Duke made a concentrated effort to protect and increase his precious herd. Despite his concern for problems caused by inbreeding among the deer, the small herd not only survived but proliferated.

The main beam of milu antlers, averaging about 25 to 30 inches in length on a mature male, forks about eight inches above the head and sweeps back in a gentle curve. Unlike most other deer, the tines growing off the main beams point downward and backward instead of upward and forward. (Père David’s deer photography courtesy of Algar Safaris)

During World War II the deer were relocated by the Duke’s heirs out of fear of being bombed into oblivion by German warplanes and rockets. Much like the emperor’s animals at the Imperial Hunting Park in Peking, the surviving deer at Woburn Abbey Preserve were managed during the second half of the 20th century through controlled hunting.

Père David’s deer are typically found in wetlands, where they feed on grasses and aquatic plants, often wading up to their shoulders in deep water. With their large, splayed hooves, the deer are good swimmers.

The average weight of an adult stag is about 470 pounds, while females weigh about 20 pounds less. The coat is reddish tan in the summer; in winter it becomes thicker and changes to a dull grey. A short mane is found on the neck and throat, and a distinct, darker-colored stripe runs along the shoulders and down the spine. The long tail has a dark tuft at the end.

Rutting dates seem to vary in different parts of the world. In most areas, the rut occurs during mid-summer. Females gather in large groups as a dominant male attempts to keep other males away from his harem. Like most deer, the stags suffer substantial weight loss during the rut.

Their antlers are particularly strange. According to renowned deer photographer and naturalist Dr. Leonard Lee Rue III, “The antlers appear to have been put on the stag’s head backwards.” The main beam, averaging about 25 to 30 inches in length on a mature male, forks about eight inches above the head and sweeps back in a gentle curve. Unlike most other deer, the tines growing off the main beams point downward and backward instead of upward and forward.

It has been reported that stags occasionally grow two sets of antlers per year. The summer antlers, which are the largest, are dropped in November after the June-August rutting season. The second set, if it appears at all, will be fully grown by January and dropped a few weeks later.

Because of their history and their relatively low numbers, Père David’s deer are still listed as critically endangered in the wild by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). (Père David’s deer photography courtesy of Algar Safaris)

Thanks to the Duke of Bedford’s descendants, Père David’s deer once again thrive in several sites in China. In 1985 a small number of deer were reintroduced in China’s Beijing Milu Park. In 1986 another small group was stocked in Dafeng Milu Natural Reserve just north of Shanghai. Several thousand more Père David’s deer are now found in captive deer herds and zoos around the world. Many of these herds are managed through controlled hunting, particularly in Argentina, England and on a number of ranches in South Texas.

Because of their history and their relatively low numbers, Père David’s deer are still listed as critically endangered in the wild by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Because the entire world’s population is descended from only a handful of animals, the lack of genetic diversity could create problems for their future survival. However, since breeding populations are now found in so many isolated areas, this worldwide distribution seems to be working in their favor.

What is it like to hunt one of the world’s rarest and most historic species of deer? Bryan Anderson of Fresco, Texas, had an opportunity to find out. An active member of the Houston Safari Club, Bryan purchased a ram hunt at a Safari Club International auction from Algar Safaris in Argentina in 2015. While researching the Algar website, Bryan discovered the outfitter offered hunts for free-ranging Père David’s deer, as well as red stag and numerous other species in southern Patagonia.

Avid Texas sportsman Bryan Anderson had long dreamed of hunting Père David’s deer. After purchasing a father-son wingshooting trip to Argentina at a Houston Safari Club banquet in 2015, he learned that the outfitter, Algar Safaris in Patagonia, maintained one of the largest herds of free-ranging Père David’s deer in the world. Bryan rearranged his trip to include a hunt for one of these rare animals, and this beautiful dream-come-true stag is the result.

“I had been reading about Père David’s deer for nearly thirty years, and they had always fascinated me,” Bryan said. “As soon as I found out that Algar Safaris had one of the largest free-ranging herds of Père David’s in the world, I decided to book a hunt for a stag. This was literally a dream come true for me, because there are very few places left in the world with quality herds. So my son and I set off on a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Bryan’s hunt took place in June 2015, and he was not disappointed. Of course, being in the Southern Hemisphere, it was early winter in Patagonia. Bryan shot a beautiful Père David’s stag, and his son shot an outstanding red stag.

“We both had the time of our lives,” Bryan said.

Since Père Davids’ deer are now hunted in several countries around the world, SCI has a category for these unique deer. Bryan’s stag scored 215 points, for which he was awarded Safari Club’s Gold Medal Trophy. In his very informative book The Encyclopedia of Deer, Dr. Leonard Lee Rue III wrote: “It was humans who brought Père David’s deer to the brink of extinction and humans who brought them back.”

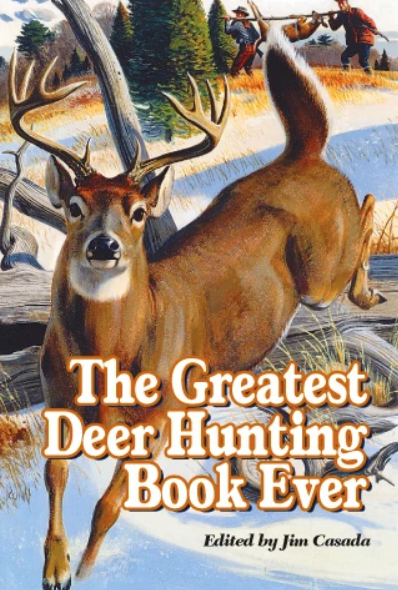

There’s something about the deer-hunting experience, indefinable yet undeniable, which lends itself to the telling of exciting tales. This book offers abundant examples of the manner in which the quest for whitetails extends beyond the field to the comfort of the fireside. It includes more than 40 sagas which stir the soul, tickle the funny bone, or transport the reader to scenes of grandeur and moments of glory.

There’s something about the deer-hunting experience, indefinable yet undeniable, which lends itself to the telling of exciting tales. This book offers abundant examples of the manner in which the quest for whitetails extends beyond the field to the comfort of the fireside. It includes more than 40 sagas which stir the soul, tickle the funny bone, or transport the reader to scenes of grandeur and moments of glory.

On these pages is a stellar lineup featuring some of the greatest names in American sporting letters. There’s Nobel and Pulitzer prize-winning William Faulkner, the incomparable Robert Ruark in company with his “Old Man,” Archibald Rutledge, perhaps our most prolific teller of whitetail tales, genial Gene Hill, legendary Jack O’Connor,Gordon MacQuarrie and many others.

Altogether, these carefully chosen selections from the finest writings of a panoply of sporting scribes open wide the door to reading wonder. As you read their works you’ll chuckle, feel a catch in your throat or a tear in your eye, and venture vicariously afield with men and women who instinctively know how to take readers to the setting of their story.

This is an anthology to sample and savor, perhaps one story at a time or in an extended session of armchair adventure. That’s a choice for each individual reader, but rest assured that on these 465 pages, there’s an abundance of opportunity to be enlightened and entertained. Buy Now