I do not mean to sound bitter about this, for perhaps it is not the fault of the wet-eared young…

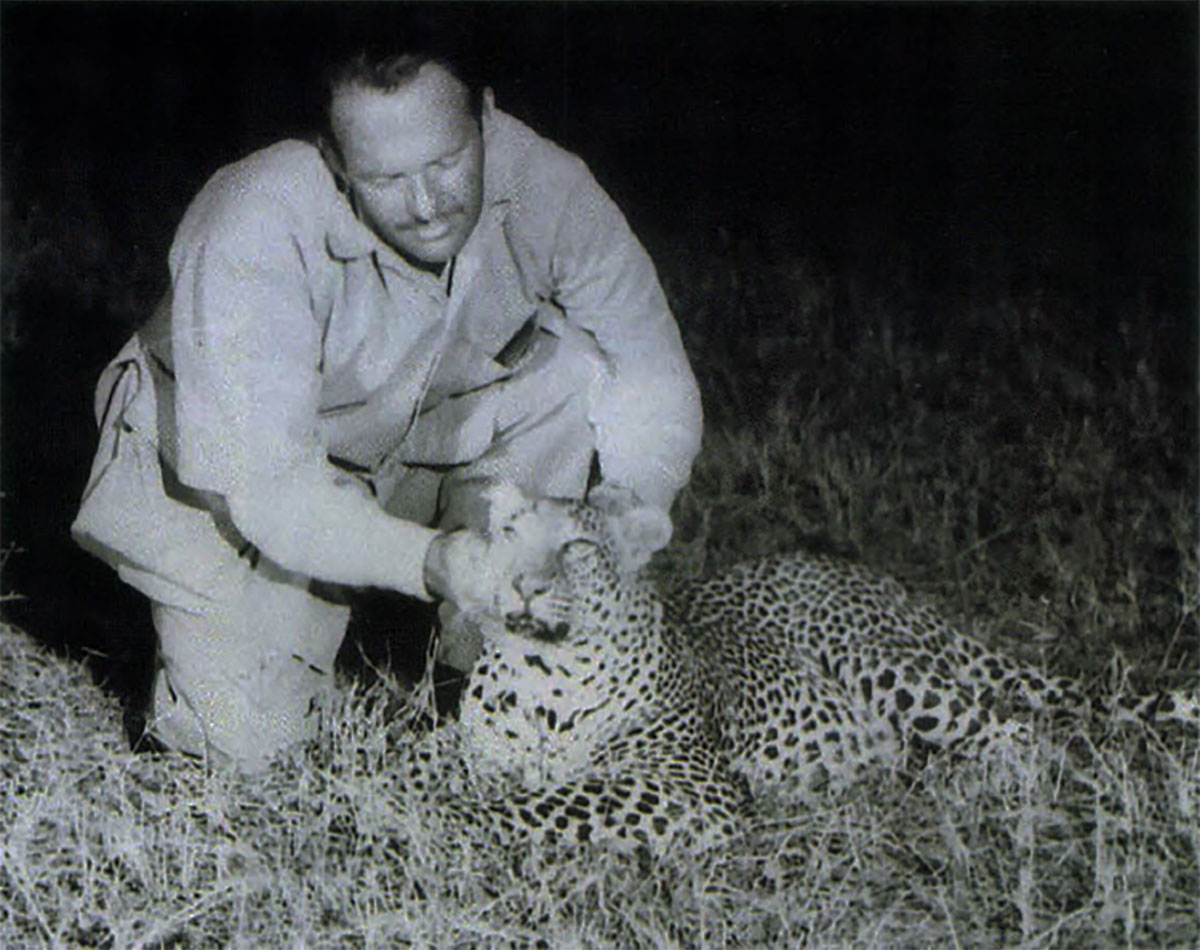

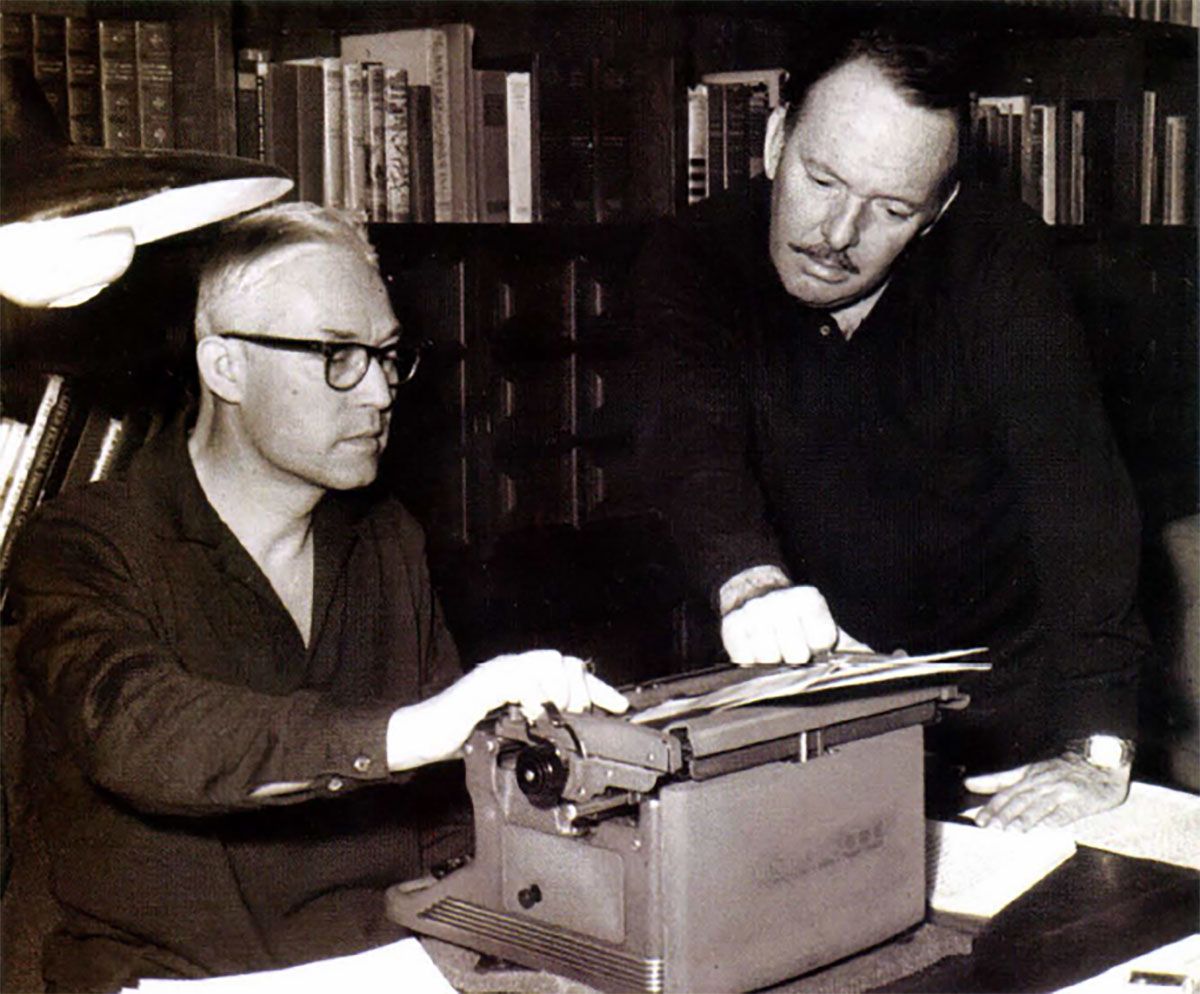

This piece is being written in a bug-ridden swamp on the banks of the sluggish yellow Tana River, in northeastern Kenya, where the big elephants bugle and the baboons swear at the hunting leopards, and the lean Northern Frontier lions rumble asthmatically just outside the camp. I have been watching, with mounting delight, the reactions of a couple of boys – middle-aged, white-haired boys — an editor friend from America and a reserved Londoner who never saw a hedgehog, let alone a lion, until recently. It has become almost a ritual with me in recent years to get back to Africa every couple of years with some newcomers to the scene, to watch the wonders through new eyes.

And I have been thinking, as I watched the response of my two old friends, that I have lived through the end of an era, and it’s a sad thought. The pure delight of these two men in the friendliness of the lions and the surly majesty of the buffaloes and the awesome bulk of the elephants was the delight of a child of my own generation, of my father’s and my grandfather’s generations. It was simple, unaffected glee, mingled with a disbelief that they were lucky enough to be in Africa at all. This could not be happening to them — one a Londoner born and bred, the other a product of the frontier state of Oklahoma when it was really woolly.

I doubt very much if the children of these men would, as the phrase has it, dig it. I am reasonably certain that many of the younger fry would scoff at us as a bunch of aging Boy Scouts for our simple pleasure in sleeping intents, being bitten by bugs, tortured by the transport and occasionally threatened by the wildlife. We have no TV. We have no moon shots or orbit efforts or no roads for hotrods. We must be corny, because we are happy with our primitive toilet facilities and the spine-cracking progress of our vehicles. To us, in our 40s and 50s, the trip to Africa — on actual safari — is the end of a boy’s dream.

The dream might have begun for one when he was a King’s Scout (the British equivalent of Eagle Scout) and for the other when he was shooting rabbits on his father’s farm in Oklahoma. For me, certainly, it started with the Old Man and a succession of dogs and guns and boats in Carolina. People like us never grow up, even when we graduate to elephants from a timid start on rabbits. We don’t grow up chiefly because we don’t want to.

Unfortunately, the day is past in America when you could walk five hundred yards from the town’s only stoplight and put up a covey of quail, or shoot ducks so close to the trolley line that you rattled shot on the cars. The old days of drawing up beside a cornfield in a Model T and having a polite word with the farmer involving casual shooting on his place are gone, oral most gone.

We have not, in recent years — certainly not in the post-World War II years — been able to build that kind of broad outdoor background into many young lives. Perhaps today’s boys will never care for the woods the way we did.

I have been tempted in the past to introduce a few younger sprouts to the fascination of safari. But having checked them out on less exotic fare, such as simple hunting and fishing expeditions, I feel disinclined to take the risk of boring them with lions or subjecting them to the torture of being bug-chewed and motionless in a leopard blind. I really would not want them to do me any favors by coming along, for a safari costs a lot of money that could possibly be better spent on hotrods or ski resorts where all the girls are.

I have lately seen a couple of instances of adult heartbreak when huntin’-fishin’ fathers tried to indoctrinate their juniors in rather lavish approaches to sea and field. The eight-year-old son of one would rather play canasta with adults, and the brood seemed consciously to be conferring a favor on the old man by coming on the boat for a couple of weeks ‘ fishing. In another instance, a friend gave his son a safari as a 21st birthday present. (What I would not have given, including my soul, for an African safari in my 21st year!) The young man remained mostly in his sack, eating and reading. He sent the professional out to kill his trophies, so that Father would not be disappointed, and all he gain ed from the adventure was 20 pounds, which he accrued while gobbling sandwiches and drinking beer in his tent.

These may be extreme cases, but the dismaying thing I run into with the younger generation these days is their cool approach to guns and shooting. I have a houseful of trophies that some of my own age-group acquaintances seem to find fascinating — a sable bull from Tabors, lions from Ikoma, big elephant teeth from the Seralippe.

But I feel apologetic when a young son turns on me and demands a justification of my right to slay God’s beautiful creatures, or some younger daughter fixes me with an eye that would make Bluebeard feel sheepish about his collection of beheaded wives. I find myself mumbling. “Well, I don’t actually shoot much anymore — I just like to look at the animals and maybe shoot a few birds once in a while.” Then the bird lovers clobber me: “And what have you got against birds?” Nothing, I just like to see them, and shoot them, and eat them. I see no difference between a fried chicken that has been butcher-killed and jointed and a breast of pheasant that has been hand-slain in the sparkling autumn woods.

I do not mean to sound bitter about this, for perhaps it is not the fault of the wet-eared young that they grew up in a world of private eyes and Jackie Gleason, or that Dagmar rather than Tarzan’s Jane was their first sex symbol. I cannot help it myself if guns and dogs and plentiful free birds and rabbits are no-longer available to the tads. There are times when I am sad over the retreat of American game and the sport derived from the hunting and shooting of it; there are times when I could weep over the certain knowledge that the vast game herds and exotic dangerous animals of Africa and India are rapidly dying off.

I am sad for myself and for those my age and older who love the outdoors and find its discomforts pleasant, who love its birds and fish and who do not feel guilty about shooting reasonably for sport and meat and relaxation. I am sad for the hunters and the fishermen who obey game laws and attempt to practice conservation. But I am not so sad for tomorrow’s generations. Perhaps they do not care if all the elephants are poached and all the rhinos slain.

I think it is a pity that super-sophistication has combined with modern pace to cheat our younger people of the sort of fun my set enjoyed as kids. I regret a kind of thinking that regards hunting as shameful, if not sinful. I do not admire a concerted attempt to sell the idea that the killing of game is a cruel sport, because no game dies a natural death, and preys as naturally upon itself as man upon man. And above all I deplore a substitution, via movies and television, of the bloody deaths of cops and gangsters and Western bad men as high adventure, notably heroic in the mind. We may have slain innocent rabbits, but we were not taught by sponsors to applaud the wholesale slaughter of people in order to peddle merchandise.

The mosquitoes here were fearful last night, and I have just plucked a tick from a tender portion of my anatomy, and for the las t day no gun has fired. Also, it has been raining. But my two middle-aged chums and I are happy here on the Tana, surrounded by wild animals and a lot of simple savages who have not yet heard of the boons of modern civilization. Perhaps my friends and I, like the elephant and the rhino, are a dying breed, but it was fun while it lasted.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appear in an issue of Field & Stream from 1963. It was later republished in the 2003 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

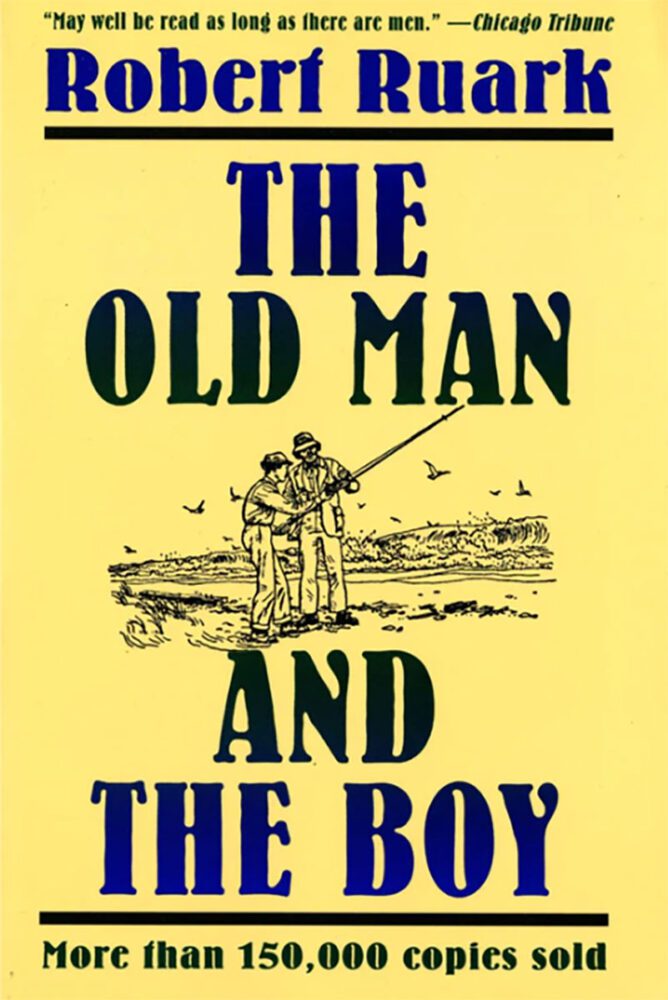

This timeless classic, originally published in 1957 and never out of print, tells the story of a remarkable friendship between a young boy and his grandfather. The Old Man and the boy hunt the woods and fields of North Carolina together; they fish the lakes, ponds, and sea. All the while the Old Man acts as teacher and guide, passing on his wisdom and life experiences to his grandson, who listens in rapt fascination. Buy Now

This timeless classic, originally published in 1957 and never out of print, tells the story of a remarkable friendship between a young boy and his grandfather. The Old Man and the boy hunt the woods and fields of North Carolina together; they fish the lakes, ponds, and sea. All the while the Old Man acts as teacher and guide, passing on his wisdom and life experiences to his grandson, who listens in rapt fascination. Buy Now