She was high-strung to a degree. When she first barked, the sound of her own voice almost scared her to death. One day she retrieved an old tin can and brought it up the front steps, and the noise it made when it got away from her made her tremble. Most pointers have a very businesslike temperament, but Patsy was as gentle as a setter. You know, some dogs are ladies and gentlemen; and some just aren’t.

While she was still so young that weeds would throw her down and briers was impassable barriers, I used to teach her to trail by shooting a starling and dragging it around the yard, turning her loose on the scent. At seven weeks of age she was broken to my .410 gun, was trailing and was pointing staunchly.

Study of Foxhound in Red, Black, and White Chalk with Blue Ink by Joseph H. Sulkowski

Her behavior with rabbits puzzled and amused me not a little. Apparently, she considered them legitimate playmates; and when one fled at her approach, she would stand and gaze after it with a most woebegone expression, as if she felt that her little comrade had deserted her. On the scent of birds of all kinds she displayed a stern demeanor, as if she had discovered her mission in life. But she wanted to romp with rabbits, and they wouldn’t play the game.

It has never seemed to me necessary to take a bird dog into the wilds to train him. Most of the work can be done right at home; and the sooner it is started, the better. Of all qualities in a bird-dog pup, give me nose. By careful and intelligent handling, almost anything can be done with a young bird dog that has a good nose. Affection and gentleness on the part of the trainer count far more than any harsh measures yet devised. If your pup has an indifferent nose, he will never amount to much in the field, even with blood, looks and pedigree in his favor.

Establishing oneself in a dog’s confidence is the foundation of training. For example, if a man ever lures a dog to him affectionately and then beats him, that dog’s trust will be shaken forever. I never whipped Patsy for anything. It took a little patience to teach her that stockings, old shoes and rugs are not meant to be lugged into obscure corners of the house and there chewed up, but I knew she was only a baby, and she learned quickly.

No man would knock the block off his year-old baby for pouring a cup of milk on the living room floor, but many a man will nearly kill a puppy for some little infraction of domestic manners. Start them very young and treat them gently and fairly. They like square shooters just as well as men do. A bird dog is just like a boy; let him run wild for the first part of his life, and you establish chances against his ever settling down to reliable behavior.

Patsy was two months old when the season for upland game opened in Pennsylvania. Now, you know how hot it is when you possess a puppy of that age at such a time. You think: “He can’t possibly give me any sport this year. This child could never take it. Perhaps later I may take him out a few times, and next year he will be a real dog. I may send him to a trainer, or to some friend in the South, where the season lasts until March. It’s hardly right to take this babe into the woods.”

Such thoughts might have been mine had Patsy not been so different. As the first day approached, and my activity with guns, shells, alarm clock and hints of what things a hunter likes for lunch apprised my wife of the coming of the Great Day, I made my revolutionary decision. I would not only take Patsy out, but I would take her into the big mountains, after the prince of American game birds — none other than the ruffed grouse, the mountain pheasant, the partridge of New England Bonasa umbellus himself.

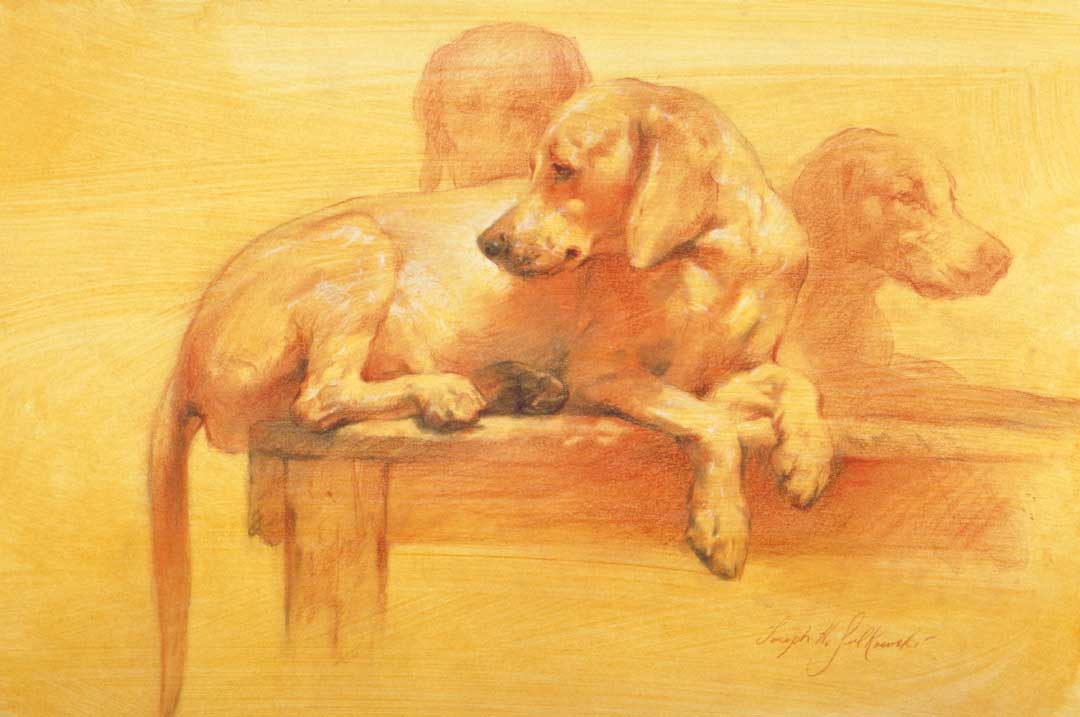

A Time to Relax by Joseph H. Sulkowski

On this first of November I arose at my usual heathenish hour. I carried Patsy downstairs to the kitchen. It was to be her first early start! I laid her in a corner, and then busied myself with getting breakfast. Soon I saw that she had gone fast asleep again! With night still huge and ominous outside, Patsy looked pathetically innocent and little, and I felt somewhat like a brute over this matter of risking her in the wilderness. But my heart was hardened, and I took her with me.

On the 15-mile drive up Path Valley, she lay fast asleep beside me, content to go anywhere if she could be with me. To a dog, a man is either a god or a devil. I have a notion that if we’d act more like gods toward our dogs, we’d get a lot further with them. I am no authority on gods and have no personal interviews to report, but my understanding is that they are kindly and tolerant, especially toward their inferiors; whereas devils are full of anger, hatred, malice and all other kinds of rascality. Certainly every puppy begins by conceiving his master to be a god; it is that master’s business never to do anything to make that dog change his mind.

I stopped my car in a lane leading from the highway into the mountains. Patsy snored contentedly. Under the circumstances I felt like the Dutchman who, seeing his beagle hound running a skunk across an open field, exclaimed, “What chanst for me to get sport today already yet?”

The day promised to be mild and still. A filmy haze lay over mountain and valley. I heard a red fox give his rasping bark. A horned owl weirdly intoned his eerie notes. Over the mountains, day came all pink and pearly. It was time to start.

I took a drink of hot tea, then gave Patsy a snifter of the same, and we started; this is, I started up the lane, carrying my grouse dog under my arm. By the time we got into the brush on the lower benches of the mountain, there was light enough to shoot. I set my puppy down, and together we began the invasion of some of my old grouse haunts — pine thickets, old orchards , laurel glens, deserted pastures where smothers of grapevine cover stone walls, abandoned mountain fields where grow the sumac and the wild rose and the green briers, on the fruits of all of which grouse delight to feed.

Anticipation by Joseph H. Sulkowski

As my preliminary training of Patsy had included encouraging her to range out, in the twilight of the dawn I was happy to see her keeping about 30 yards ahead of me, a white fairy in those dusky solitudes. A light frost was beginning to melt, making conditions ideal for Patsy to pick up a trail.

After some 15 minutes we came to a gentle slope, on the incline of which was a pile of dead pine brush. While 30 yards away from this my little princess hesitated; then she drew to a dead point. A damp air was breathing from the pine-tops toward her. What did she have? There are plenty of quail in these coverts, but my mind told me that she had a grouse; and it was the first one she had ever winded. If she had hunted grouse for 10 years, she could not have acted more perfectly.

Easing around until I got behind her, and scanning the country ahead to calculate just where his lordly majesty would go when flushed, I walked in carefully. When I came to Patsy, she did not break point, but she did look up at me, as if saying “I’ve got something; I only hope it’s what you want.”

Passing her, I walked slowly up toward the brush-pile. Three grouse hurtled out, each choosing a different direction. I have always found it a most difficult thing to make a double on grouse when several get up together. When I try it, I usually miss all of them. One of these was perceptibly larger than the other two; an old cock he was, and when he thundered up he headed for his mountain home. As he bore to the left, I had to lead him; I also shot above him.

By good chance, this old cock got in the way of my shot, closed his wings and pitched downward with great velocity. I called Patsy. But at the sound of the gun she did not break point! No sir; there she was planted. Walking back, I patted and praised her; then I picked her up and carried her to where her first grouse lay. She tried to retrieve him for me, but he was too big. Stumblingly she dragged him toward me.

All this called for some special demonstration on my part; so I sat down, took my baby in my lap, stroked her sensitive head, and otherwise gave her to understand that she was behaving like a champion. She kept sniffling delightedly at the big bird, and I knew that from that day forth I was to have a grouse-minded dog.

Wandering a little higher into the hills, we came to a rivulet gushing along among mossy rocks. Here were kalmias and great thickets of greenbriers under the oaks and hemlocks. Patsy, who had now traveled about a mile, was showing signs of getting tired. Several times I stopped for a few minutes to rest her. Coming to a dense patch of laurel, I sent Patsy in for a scout. I could see the open woods on all sides of this thicket, and kept watching for my dog to come out. But no dog.

“It must be a point,” thought I, sidling ahead through the dense greenery.

All was silence. I didn’t want to call for fear of flushing something out of range. I had a sudden apprehension about a rattlesnake. This is bad country for snakes, though they are rarely abroad after the first frosts. Besides, if a snake strikes a dog, the dog always gives notice by a sharp yelp. No sound had come from Patsy. I was puzzled, and was greatly relieved when I saw her standing with both forepaws on an old dead chestnut log. She was almost hidden by the over-arching laurels.

At first I thought she had come to the log and, finding it too much for her, was waiting for me to help her over. But then I caught in her eyes that dreamy look dear to every lover of a bird dog: she was fast on point. I walked in carefully. When I got to Patsy, I stopped to stroke her head and stepped over the log. Nothing happened. Well, I thought, an old dog is often fooled; what can you expect from a youngster?

A little circling among the bushes brought me no results. I returned to Patsy. “Lady,” I said, ‘scuse me, but you’re a liar.”

Still the elf held her stand. “Now, ain’t that sumpin’?” I muttered, and began to glance around for a land turtle, the scent of which will sometimes mislead even a champion bird dog. But nary a turtle. I picked Patsy up, and to my surprise she was as stiff as a little statue! Her whole body seemed to resent my interfering with her business. The dream-light never left her eyes. I set her down, and she continued to point, only this time she took two steps to the left: and she seemed intent upon the log.

Just then I heard a slight movement in the dry leaves in the shelter of the old chestnut log. In another second, two grouse tore away from the side of the log, where they had been all along, as Patsy had so faithfully been trying to tell me. They went down the mountain. At 50 yards, as they hurtled into a smother of hemlocks, I shot rather blindly, and could see no result except a single small feather drifting idly downward.

“If I had done half as well as you did,” I told Patsy, “we’d have all we are allowed in Pennsylvania in one day.”

With no faith that I had done anything, I came to the place where my dead grouse should have lain. As I expected, there was no sign of it. Here was a perfect shambles of logs and limbs, the debris of a lumbering operation. I had a hard time getting along, and it was much worse for Patsy. Just as I was on the point of carrying her out of this hopeless thicket, she came to a stand. As she was under a deep tangle, I laid down my gun and literally had to crawl to get to her. Two feet in front of her nose, wedged under a log, was my grouse! When he had struck the ground, he had had life enough left to dash to hiding, but he was now dead. I retrieved him and my baby champion.

“It’s the limit,” I said, meaning both kinds, and, picking up my gun, started back for the car. Patsy is but one of many bird dog puppies that I have started very early. If this can be done normally and gently, it’s the thing to do. Of course, I have been fortunate in living on the outskirts of a village, and quail nest right by my house. But many fundamentals can be taught a puppy without actual access to live game birds. Most of the books about training bird dogs have a good deal to do with reclaiming vagabonds and reforming criminals. But if you will get a puppy of patrician blood, make him love you, and start him on his career while he is still toddling, most of the difficulties that come with the breaking of a year-old, senseless, half-wild dog will never appear.

A bird dog has a real mission in life. Make this clear to him during the first three or four months of his life, and the chances are that, instead of having to show him further how to hunt, from then on he will be teaching you the finer points of the game.

First published in the September 1935 issue of Field & Stream, this is one of Archibald Rutledge’s best-known stories of bird dogs and bird hunting.

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski.

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski.

Acclaimed as one of America’s premier dog and sporting artists, Sulkowski shares his personal conversation with the outdoor life in a style of Poetic Realism. Influenced and guided by the hands of the Old Masters, he creates fluid brushstrokes that imbue his canvases with a compelling blend of light, atmosphere, and spatial effects that bring his passion for the sporting life into vivid focus for the viewer.

Whether it’s still-lifes, dog paintings or scenes of hunters and anglers, Joseph Sulkowski derives his inspiration from personal contact with the natural world. He carries out his visions through a lifelong discipline to his craft in which hand-ground paints, carefully prepared oils and varnishes, and handcrafted linen canvases and gessoed panels play a vital role in the quality of each work of art.

All this and more about the immensely gifted artist is detailed by author Brooke Chilvers, one of the foremost experiets on wildlife and sporting art. Altogether, the large-format, 240 pages book features more than 180 paintings and dozens of sketches.