Similarly, he was in frequent contact with Henry Edwards Davis, author of The American Wild Turkey, a work many consider the finest ever written on the subject. Davis even sought Whedon’s advice on a publisher for his sporting memoirs (in 2010 those finally saw the printed light of day as A Southern Sportsman: The Hunting Memoirs of Henry Edwards Davis, with Ben Moise as editor and the present writer contributing an Introduction). Indeed, Parker talked or corresponded with every old timer he could find, and right up until his final months eagerly researched matters connected with call development and the history of turkey hunting.

If one examines the whole of Whedon’s career, which saw him hunt turkeys for a full six decades, he must be considered one of the sport’s grand masters in his own right. Or, as a friend put it when he learned of his death: “He was a genuine old-time turkey man. With his passing we may have seen the last of them.”

There is much truth to that comment. Whedon commenced his long run as a turkey hunter while a student in the University of North Carolina’s law school. One of the first turkeys he killed was in nearby Willow Oak Swamp, and anyone who has read John Terres’ story, “The Black Gobbler of Willow Oak Swamp” in From Laurel Hill to Siler’s Bog, will be interested to learn that Parker’s gobbler was the running mate of this hermit turkey.

Parker was largely self-taught, although he made a point of learning everything possible from personal contact with experts and through correspondence. He read everything that had been written on the sport, closely followed the activities of state wildlife departments in the early stages of restoration efforts and hunted at every opportunity in both fall and spring. Such was his devotion to the wild turkey that throughout fifty years of practicing law he was never part of a law firm or involved with partners. Parker preferred a one-man practice. When I once asked him about that, his reply was classic Whedon, “I have always wanted to be my own boss because any other situation would have had the potential to interfere with my turkey hunting.”

Parker’s obsession with the sport encompassed all aspects of the turkey’s world—shrewd observation and appreciation of natural history, solid grounding in the art of callmaking, serious study of turkey hunting literature, devotion to training dogs for fall hunting, and a studied willingness to share his accumulated wisdom (by the time I got to know him it was vast) with a select few. He had to consider you worthy, and determination of one’s merits came through close observation in the field, a shrewd appreciation of what he considered the proper mindset for a turkey hunter, and eagerness to learn. Perhaps sharing a few anecdotes from my many days afield with him will afford insight into his approach to and thinking on the sport.

We were first introduced by a mutual friend, Charlotte, NC, lawyer and bird hunter Dave Henderson, the author of a number of fine books on his adventures with quail, bird dogs and related topics. When Parker learned I belonged to a hunting club that controlled land where there were lots of turkeys, and when I mentioned I had no idea how to hunt them, he said, “Come spring, let’s check it out and we’ll decide whether you really want to become a turkey hunter.”

We did just that, and on our first hunt he called a bird in from the roost that I killed. Mine was the quintessential “trigger man” role, because all I did was set up where instructed, keep still and shoot the bird when it strutted up an old logging road exactly as Parker had predicted.

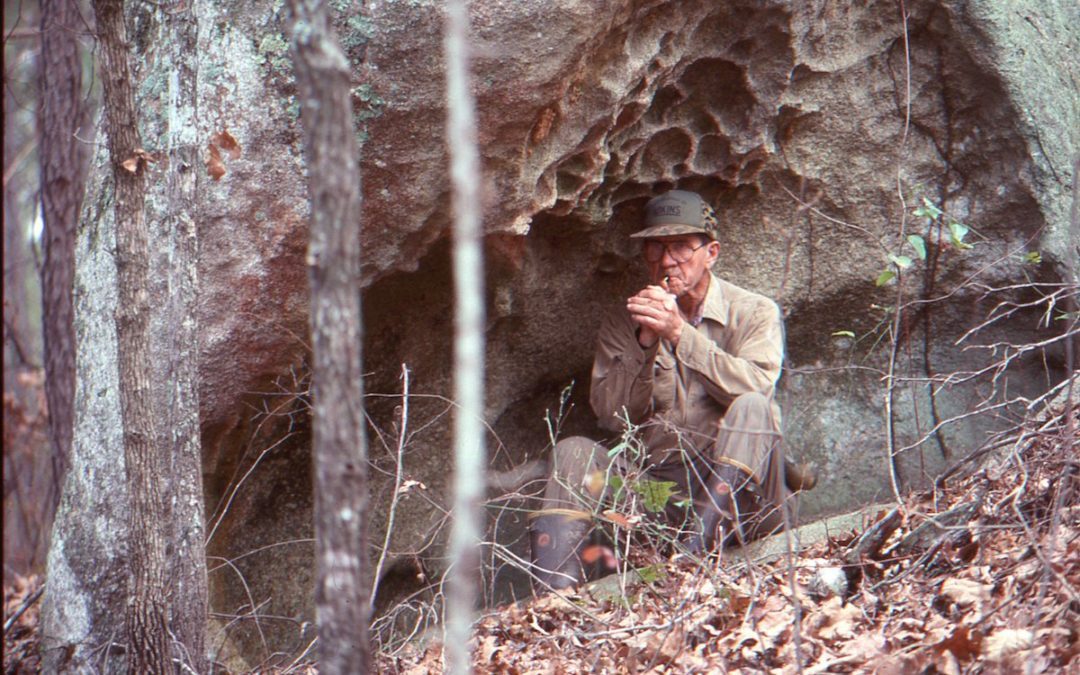

Even when feeble and able to walk only a short distance, Parker persevered in his passion.

As we stood admiring the turkey, three things happened. First of all, he said, “That’s how it’s done; now you are on your own.”

He pretty much meant it, and I spent the remaining 30 days of that season hunting every morning and most afternoons, missing three birds, probably spooking a dozen and generally messing up with the glorious abandon known only to the rankest of novices. There were lots of mournful evening phone calls asking what I had done wrong. Each time Parker patiently listened, suggested what I might have done, and said, “Sleep on it and try them again tomorrow morning.”

The second thing growing out of killing that first turkey was one of an untold number of great tips he offered me over the years.

“Let’s go find your spent hull,” he said. “When you get home, write up a little description of this hunt and stick that slip of paper, along with the bird’s beard, in the shell. If you like turkey hunting as much as I think you will, there’ll come a time when you can’t recall the details of every hunt. But all you will have to do to make the past come alive is to go to the place you store the shell, story and beard and your memory will make a wonderful journey of time travel.” I followed his advice, and today I own some three hundred shells preserving pieces of the past.

Finally, he was struck by the way I kneeled, reverently and smoothed the feathers of the gobbler while commenting on its beauty.

“You are exactly right,” Parker said, noting how the early morning sun reflected off the breast feathers, and then added that his former wife always reckoned “there’s nothing uglier than a dead turkey.” He chuckled. “Maybe that’s why we are no longer married.”

Whedon was my mentor, as was the case with perhaps a score of other dedicated turkey hunters, and his patient tutelage and willingness to share his vast experience may well rank as his greatest legacies. Yet his ability to share the sport he loved with a select few—and believe me, he was selective when it came to understudies—was but one aspect of his multi-faceted contributions to turkey-hunting posterity.

In 1984, in company with two other departed giants of the sport, Larry Hearn and noted wild turkey biologist and writer Lovett E. Williams, he founded Old Masters Publishing. That resulted in three of the most important (and rarest) books from the early annals of turkey hunting, Edward A. McIlhenny’s The Wild Turkey and Its Hunting, Simon Everitt’s Tales of Wild Turkey Hunting, and Henry Edwards Davis’s The American Wild Turkey being reprinted.

Then there were Parker’s activities in the fields of call collecting and callmaking. As a callmaker, he was the essence of practicality melded with a keen eye for beauty. With Larry Hearn he developed and patented the Crown trumpet, an expandable suction yelper of great versatility. However, Parker’s real genius shined most brightly in wingbone calls and Jordan yelpers. His two-piece Spirit yelpers, adorned in the later stages of his life by scrimshaw work from the hands of a Catawba Indian, combined form and function in a perfect marriage. Similarly, he experimented with a variety of materials for the trumpet end of yelpers or as useful appurtenances to them. Among them were use of 28-gauge brass shell tops for mouth stops, black cane in Jordan yelpers (The Jordan II and The Jordan III models), .410 hulls as a trumpet end (The Poult call), rifle brass as call joints, and more.

In a remarkable feat of research and experimentation, Parker figured out the “formula” Simon Everitt used to make his collapsible Roanoke River calls and thus was reborn the Simon Everitt Roanoke River yelper. With this breakthrough rediscovery Parker literally rolled back the pages of history.

Parker at the peak of his career.

Parker was never an especially prolific producer of calls, thanks in no small part to his insistence on perfection, and as a result, anything he crafted is already highly collectible and certain to become more so. As John McDaniel stated in his chapter “Call Makers” in The American Wild Turkey, calls such as those Parker made are “like a Ward brothers decoy . . . a work of art that is also functional. It will remain an important part of the American story. . . . We as turkey hunters should not be satisfied until the recognition the great turkey-call makers receive is comparable to that of the artists who produced the finest decoys.”

Fortunately, as he did with his hunting wisdom, Parker gladly shared his thoughts and knowledge on callmaking with those whom he felt worthy of carrying on a proud tradition, so his contribution to the story of callmaking and turkey hunting in this country will continue. Gene Gardner served dual apprenticeships—as a hunter and a callmaker—under him and today carries on the latter as Parker’s heir in their joint venture in producing calls. Also, Parker took a liking to Ralph Permar, a well-known figure in today’s custom callmaking world, and gave him the go ahead to make Roanoke River yelpers after the Simon Everitt model.

Right to the end of his life Whedon experimented with calls. The next to last time I visited him, when he was weak, bedridden in a nursing home and only periodically in full possession of his once astounding mental faculties, he had taken a pen apart, had the ink-holding tube out, and was studying its possible use as the suction end of a yelper that would produce keen, high-pitched yelps of a young hen.

When it came to calls made by others, Parker was never a die-hard collector as such. Nonetheless, because of his interest in the work of great callmaker/hunters, he came into the possession of an incredible array of rare and valuable calls.

He owned Henry Edwards Davis’s favorite box call for decades, eventually selling it for the highest amount ever paid for a turkey call—just over $55,000 dollars. He also had a call that had been used by Simon Everitt and bore the man’s name, a prototype of one of Turpin’s most important efforts, and dozens of other calls of the type that collectors cherish. Wisely, he sold virtually all of those as his health declined and he reached a point where he could no longer venture afield. In this context it should also be noted that he helped Howard Harlan a great deal with research on his seminal work, Turkey Calls: An Enduring American Folk Art.

One other aspect of the turkey hunting portion of Whedon’s career must be mentioned. He was an avid devotee of the traditional way of turkey hunting, in the fall and winter with a dog. He was instrumental in founding the American Wild Turkey Hunting Dog Association, and his contribution to a little book by Jon L. Freis, Wild Turkey Dogs: Choosing, Training and Hunting, is invaluable. Simply entitled “Training a Turkey Dog,” it is a succinct masterpiece with a typical Parkerism at the outset stating that except for obedience commands “the dog trains you.” Parker owned a number of fine turkey dogs over the years, and for anyone interested in a canine companion this is must read material.

Along with being a truly great figure in the world of turkey hunting, Parker was a man of Renaissance-like qualities that saw his ever-questing mind and powerful intellect reach out in many directions. His frequent letters to the editor of the Charlotte Observer were pointed, razor-sharp and often punctured balloons floated out by what I once heard him characterize as “pompous jackasses.”

He was a first-rate bass fisherman and once the spring turkey season had come and gone, Parker loved to float area rivers in a canoe. He owned a little cabin nestled on a beautiful hill overlooking the Uwharrie River, and his retreats to that spot gave him great pleasure over the years. A voracious reader, he was well versed in a remarkably wide range of fields of literature and history. While I never saw him perform in court, I gather he was a formidable legal adversary in such a setting. For me though, he was just a staunch friend and grand mentor, and every time I think of him it is with fondness and realization that I should have pried and probed in his vast storehouse of turkey wisdom even more than I did.

Parker in his den demonstrating use of a wingbone yelper.

From spring hunting to the enduring tradition of fall dog hunting, from the secrets of mastering the wingbone call to a myriad of insights into turkey lore, Parker Whedon gave me a gift beyond compare. He set me striding down the unending road of becoming a turkey hunter. For that, for a hundred dawns with the dulcet tones of awakening spring in my ears and him at my side, for the joys of seeing his dog, Luke, scatter a flock like thistle seeds caught in a dust devil, and for the simple privilege of being befriended by a turkey man of the old school, I will be eternally grateful. In closing, it seems appropriate to share two additional tidbits, one focusing on the graveside service when he was buried and the second a listing of some of his pithy thoughts I came to consider “Parkerisms.”

As my wife and I got out of my truck at the graveside service honoring Parker, I slipped the lanyard holding the first wingbone call he made for me around my neck. Crafted with bones from my first gobbler and first fall hen, it features his special design of a brass cartridge enclosing the joint between the bones and surgical tubing affixed internally for air tightness.

“At some point in the service,” I told my spouse, “there will be an opportunity to offer some soft yelps and clucks to honor his memory.”

Sure enough, during one of a series of eulogies provided by friends from his remarkably diverse set of acquaintances, an artist who shared Parker’s passion for protecting the Catawba River mentioned having been given a Spirit yelper as a thank you for his exquisite painting “The Great Falls of the Catawba” commissioned to raise funds for the Catawba River Conservancy.

As the artist spoke, he displayed the yelper and said, “I wish I could use it.” That was opening enough. I immediately put my wingbone to my mouth and produced some clucks followed by a series of yelps. Another individual for whom Parker had served as a turkey mentor did the same. After the service I introduced myself to the artist and, as we chatted, he said that Parker had once commented to him, “I hope someone will call a turkey at my funeral service.” To be present and able to yelp him home was a comfort and a joy. He now roams a place where flock scatters are always good, where woods always ring with gobbles, and where, as Parker might have put it, a man may hunt His Majesty in incomparably beautiful surroundings.

“PARKERISMS”

As might be expected from a trial lawyer, Parker Whedon had a rare way with words. Eloquent, gifted with a truly impressive vocabulary, and about as widely read as anyone I’ve ever known, he was a flowing fount of turkey wisdom. Here’s a sampling of “Parkerisms.”

“Get his (a gobbler’s) attention and lay a heavy dose of silence on him.”

“The only absolute in turkey hunting is that there are no absolutes.”

“There’s never been a turkey that needed a second opinion on danger or, for that matter, anything else.”

“Sometimes I could swear that the ground just swallows up turkeys.”

“Almost everyone reaches the point at a fairly early stage in his career where he thinks he’s a turkey-killing machine. Usually that attitude is dispelled with a turkey administering an object lesson in disappointment.”

“There are liars, there are sporting liars and then there are turkey liars. The latter are a rare and special breed.”

“Most of these modern Johnny Jump-ups on the turkey scene call too loud, too long and too often.”

“Woodsmanship is the most important and least understood aspect of being an accomplished turkey hunter.”

Jim Casada, in what he describes as “an enduring labor of love,” provides an in-depth look at 27 giants of the turkey-hunting world, men who have made their mark and shaped turkey-hunting history dating back to its recorded beginnings. This is a book sure to appeal to anyone who rejoices in the sport and its rich, enchanting past. Buy Now