Black magic, junk pistols and lessons learned thereby.

Pappy was county coroner 36 years; an elected position. It didn’t pay much, but he got to keep all the murder and suicide guns, and he was the only man who could arrest the sheriff, which he did when the new sheriff went crazy in court and slapped hell out of the jury foreman, a retired Marine brigadier.

I ain’t making this up, here on the Carolina coast where truth beats fiction every damn time. Folks all said voodoo drove the new sheriff crazy, that old black magic come over on the slave ships.

Two sheriffs, the old and the new.

The new sheriff was a highway patrolman, put up for election by the Baptist elders who could not stomach the old sheriff, who turned to voodoo to make himself bulletproof. He got shot at numerous times, but no suspect was ever charged for the offense.

He stood up in court and bellered, “No murder was attempted because no murder was possible. It was just like he shot at me from a mile away.”

But pride, the Good Book says, cometh before the fall.

I liked both men well enough. The old sheriff let me hunt quail on his place, and the new sheriff called me “Billy Goat,” as I was sweet on his daughter. Besides, I was too young to vote. It was a long and vitriolic campaign with an unprecedented three recounts.

The old sheriff did not take well to defeat, and the new sheriff’s troubles were continuous and manifold, the slap-up being the final straw. The new sheriff retreated to his house, pulled the phone out of the wall, lay his big service revolver on the kitchen table, and sat down to see what would happen next.

Folks all said voodoo drove the new sheriff crazy, that old black magic come over on the slave ships.

The County Commission sent Pappy in with a warrant and a dated but unsigned letter of resignation. Pappy came out ten minutes later, leading the new sheriff by the hand, the signed letter and the sheriff’s big pistol hanging out of his back pocket.

The governor appointed Pappy to fill out the remainder of the term. As both coroner and sheriff, Pappy was briefly immune from arrest, one of only two men in the United States. The other was the president, Richard Milhous Nixon.

Lesson one: Don’t mess with a voodoo man.

The murder and suicide weapons, bushels and bushels of them over the years, was a motley collection ranging from a fine Smith & Wesson Highway Patrol model and a lovely flattop Ruger .44 to a great and derelict assortment of .32s and .38s. There were Spanish copies of Colts; Harrington & Richardsons; Iver Johnson Owls Head five shots, rusted all to hell, chrome plating peeling, friction tape grips, actions loose as a spavined mule. A God’s wonder any of them ever fired.

I soon learned Pappy’s value system: If it was a gun and it fired, it was good. If it didn’t fire, it was still good. He took me to the range, an event much appreciated and anticipated, a dirt pile with pallets and beer cans to ventilate.

“Be careful with this gun, Son. The last time it was fired, it killed a man.”

“Yes, Pappy.”

Lesson two: A bullet ain’t got no eyes.

When Mammy took to mumbling over the clutter of pistols in the corners, the whale skull, the cast nets, foghorns, bilge pumps and assorted truck Pappy fetched home over the years, Pappy was obliged to take inventory. He gathered up a dozen or so more hopeful pistols from the prospects, then pointed to the rest.

“Your momma is fixing to give me fits. Take these damn things to Savannah and trade ’em for something. But if one ever shows up in this county as evidence again, you gonna get your butt whupped.”

“Yes, Pappy.”

I didn’t want to get my butt whupped, so I took them clean to Jacksonville, where I swapped 60-some pounds of pistols for a single 2-pound, 8-ounce 1911 Government .45, loose as some of the pistols I swapped for it. I was driving by then, a 1957 Chevy, four-door, six-cylinder, two-speed slush-box automatic transmission with mud-grip recapped tires. They howled and hammered at 60, so I kept her below 55—easy enough in those days.

“You did good, Sonny. Mighty good.”

They were his junk pistols, so now it was his .45. He wrapped it in an oily rag and put it in his dresser drawer along with his socks and his great-grandpappy’s medals from the Mexican War. Mammy was mighty gratified.

Lesson three: Don’t get your butt whupped.

Mexican War? Yep. Company F of the Palmetto Regiment, uphill 250 miles from Veracruz to Mexico City, the Mexican cavalry swarming them the whole way, more men dead from disease than bullets. But 120 years later I was failing Spanish 101. Maybe not failing. I couldn’t count to 100, but I could order a beer and talk pistolero, not immediately transferable into high school credits. It didn’t sit well. Pappy scowled and cussed over my D+.

“Son, you bring that up to a B and I’ll give you that .45 you brought back from Florida.”

Yes, Pappy.

There were Spanish copies of Colts; Harrington & Richardsons; Iver Johnson Owls Head five shots, rusted all to hell, chrome plating peeling, friction tape grips, actions loose as a spavined mule. A God’s wonder any of them ever fired.

And when I came home with an A-, he sweetened the deal with a thousand rounds of surplus ammunition he got from the new sheriff six months before he had to arrest him.

If you’ve ever shot a 1911, you’ll know it makes an ungodly racket. Lord knows it’s loud enough, but that ain’t the worst of it. A man might stand a .38 Special, a .357, a .44 Special, even a .44 Magnum, but a 1911? There’s a high-pitched, metallic, ear-drum-busting clang from the workings of John Browning’s genius, steel moving faster than you can see right there in your hand? Yep. Ear protection was a mere curiosity in those days, an intellectual consideration at best, and ringing ears at midnight was just a testimony of a good day slinging lead. I can still speak tolerable Spanish, exercised in Costa Rica and Argentina, but I have trouble hearing the replies.

Lesson four: Learn your Spanish and plug your ears.

Time came to leave home. I wrote a story about not shooting a doe on a deer drive, and it won me a full ride to the University of Iowa, where I aimed to take up writing as a trade. Pappy didn’t like the notion.

“And just what are you planning to do, Son, with a Master of Fine Arts in English?”

“I don’t know, Pappy. Maybe come home and run a shrimp boat.”

If I told you his response, it would not be printed here. Last time Pappy left home was in ’44, when he ended up in the jungles of Saipan on the receiving end of the war’s last great Banzai charge. He had to move the machine guns three times to be able to see over the bodies, and he didn’t cotton much to travel after that. He crossed the county line only when absolutely necessary.

I did good about my writing, but Pappy didn’t get to see much of it, only the first two or three books. His initial skepticism turned to considerable pride. Mammy was baffled.

“He used to look at you like you had three heads. Now you’re his alter-ego.”

After I started making a little money, I bought Pappy pistols—a couple of large-frame Smiths in velvet-lined presentation cases, a Colt single-action .22, and a lovely commercial 1911 with adjustable sights and rosewood grips. I made the funeral but skipped the wake. When I didn’t show, the relatives swooped in and made off with all of them.

Didn’t matter as much as you might suspect.

Lesson five: Pay your debts, double if those debts are of the heart.

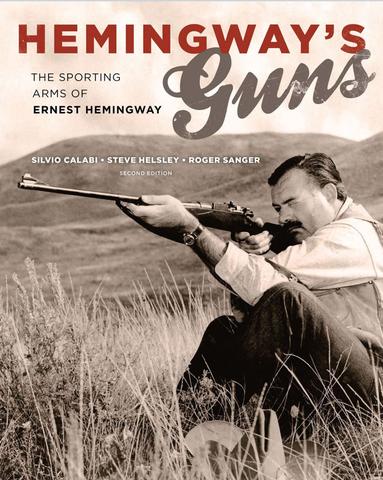

Ernest Hemingway’s friend A.E. Hotchner once described a “yellowed four-by-five picture of Ernest,” shown him by Hemingway, “aged five or six, holding a small rifle. Written on the back in his mother’s hand was the notation, ‘Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when 2½ and when 4 could handle a pistol.’”

Ernest Hemingway’s friend A.E. Hotchner once described a “yellowed four-by-five picture of Ernest,” shown him by Hemingway, “aged five or six, holding a small rifle. Written on the back in his mother’s hand was the notation, ‘Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when 2½ and when 4 could handle a pistol.’”

Firearms and shooting infused Hemingway’s existence and thus his writing. He was a member of his high-school gun club and went to war when he was eighteen. He hunted elk, deer, and bear in the American west and went on two extended African safaris, which figured hugely in his writing and changed his life. To the day of his death, Hemingway remained an avid hunter, first-class wingshot, and capable rifleman.

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Buy Now