I suppose that there are other things that make a hunter uneasy, but of one thing I am very sure: that is, to locate and to begin to stalk a deer or a turkey, only to find that another hunter is doing precisely the same thing at the same time. The feeling I had was worse than uneasy.

It is, in fact, as inaccurate as if a man should say, after listening to a comrade swearing roundly, “Bill is expressing himself uneasily.”

To be frank, I was jealous; and all the more so because I knew that Dade Saunders was just as good a turkey-hunter as I am—and may be a good deal better. At any rate, both of us got after the same whopping gobbler. We knew this turkey and we knew each other; and I am positive that the wise old bird knew both of us far better than we knew him.

But we hunters have ways of improving our acquaintance with creatures that are over-wild and shy. Both Dade and I saw him, I suppose, a dozen times; and twice Dade shot at him. I had never fired at him, for I did not want to cripple, but to kill; and he never came within a hundred yards of me. Yet I felt that the gobbler ought to be mine; and for the simple reason that Dade Saunders was a shameless poacher and a hunter out-of-season.

I have in mind the day when I came upon him in the pinelands in mid-July, when he had in his wagon five bucks in the velvet, all killed that morning. Now, this isn’t a fiction story; this is fact. And after I have told you of those bucks, I think you’ll want me to beat Dade to the great American bird.

This wild turkey had the oddest range that you could imagine. You hear of turkeys ranging “original forest,” “timbered wilds” and the like. Make up your mind that if wild turkeys have a chance, they are going to come near civilization. The closer they are to man, the farther they are away from their other enemies. Near civilization they at least have (but for the likes of Dade Saunders) the protection of the law. But in the wilds what protection do they have from wildcats, from eagles, from weasels (I am thinking of young turkeys as well as old) and from all their other predatory persecutors?

Well, as I say, time and again I have known wild turkeys to come, and to seem to enjoy coming, close to houses. I have stood on the porch of my plantation home and have watched a wild flock feeding under the great live oaks there. I have repeatedly flushed wild turkeys in an autumn cornfield. I have shot them in rice-stubble.

Of course, they do not come for sentiment. They are after grain. And if there is any better wild game than a rice-field wild turkey, stuffed with peanuts, circled with browned sweet potatoes and fragrant with a rich gravy that plantation cooks know how to make, I’ll follow you to it.

The gobbler I was after was a haunter of the edges of civilization. He didn’t seem to like the wild woods. I think he got hungry there. But on the margins of fields that had been planted he could get all he wanted to eat of the things he most enjoyed. He particularly liked the edges of cultivated fields that bordered either on the pinewoods or else on the marshy rice-lands.

One day I spent three hours in the gaunt chimney of a burned rice-mill, watching this gobbler feeding on such edges. Although I was sure that sooner or later he would pass the mouth of the chimney, giving me a chance for a shot, he kept just that distance between us that makes a gun a vain thing in a man’s hands. But though he did not give me my chance, he let me watch him all I pleased. This I did through certain dusty crevices between the bricks of the old chimney.

If I had been taking a post-graduate course in Caution, this wise old bird would have been my teacher. Whatever he happened to be doing, his eyes and his ears were wide with vigilance. I saw him first standing beside a fallen pine log on the brow of a little hill where peanuts had been planted. I made the shelter of the chimney before he recognized me. But he must have seen the move I made.

I have hunted turkeys long enough to be thoroughly rid of the idea that a human being can make a motion that a wild turkey cannot see. One of my woodsman friends said to me: “Why, a gobbler can see anything…. He can see a jaybird turn a somersault on the verge of the horizon.” He was right.

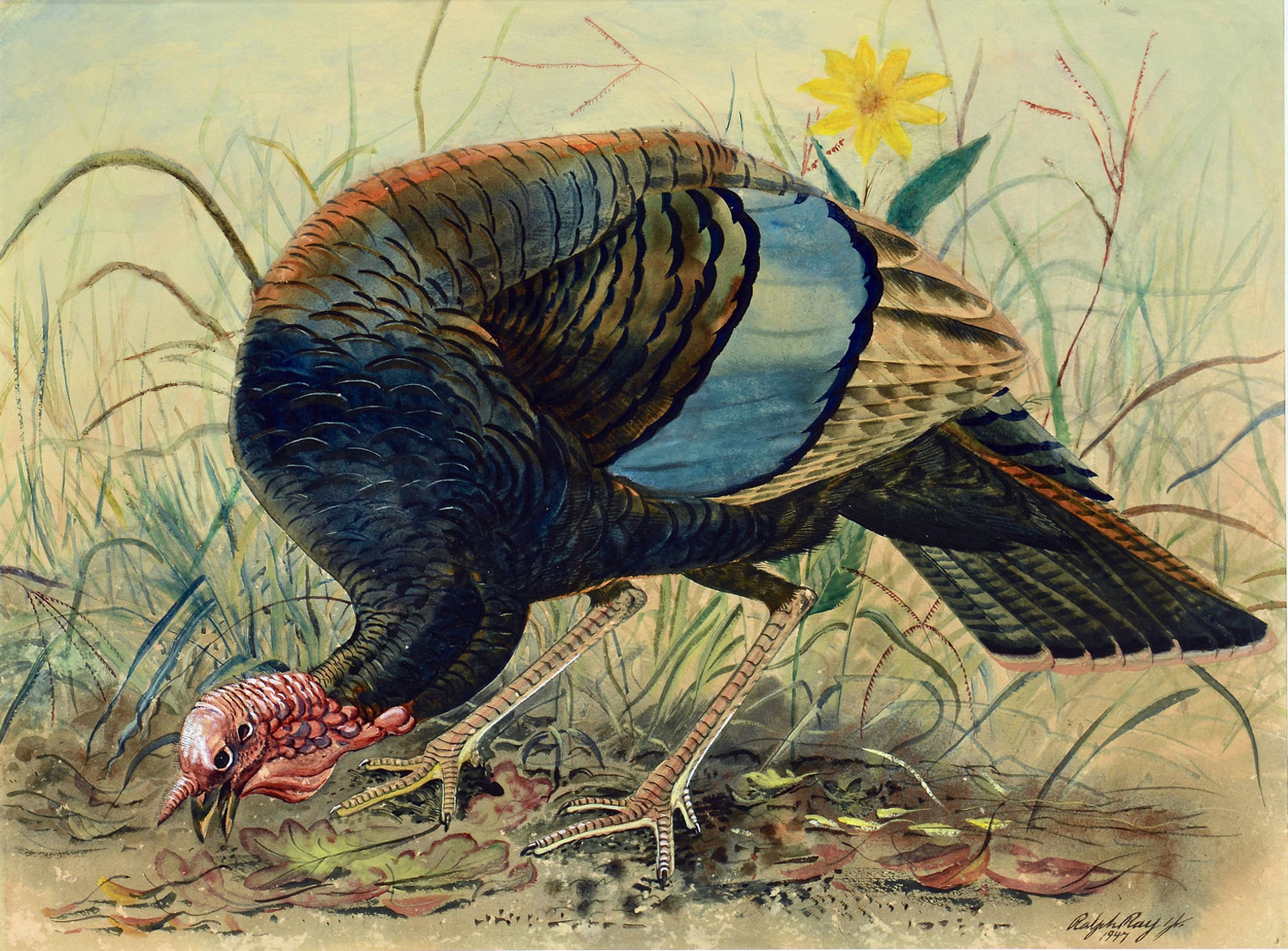

Turkey, 1947, by Ralph Ray Jr. (American, 1920-1952), watercolor, 11 1/4 x 15 1/4 inches.

Watching from my cover I saw this gobbler scratching for peanuts. He was very deliberate about this. Often he would draw back one huge handful (or footful) of viney soil, only to leave it there while he looked and listened. I have seen a turkey do the same thing while scratching in leaves. Now, a buck while feeding will alternately keep his head up and down; but a turkey gobbler keeps his down very little. That bright, black eye of his, set in that sharp, bluish head, is keeping its vision on every object on the landscape.

My gobbler (I called him mine from the first time I saw him) found many peanuts, and he relished them. From that feast he walked over into a patch of autumn-dried crabgrass. The long, pendulous heads of this grass, full of seeds, he stripped skillfully. When satisfied with this food he dusted himself beside an old stump. It was interesting to watch this; and while he was doing it, I wondered if it was not my chance to leave the chimney, make a detour, and come up behind the stump. But of course, just as I decided to do this, he got up, shook a small cloud of dust from his feathers, stepped off into the open and there began to preen himself.

A short while thereafter, he went down to a marshy edge, there finding a warm, sandy hole on the sunny side of a briar patch, where he continued his dusting and loafing. I believe that he knew the stump, which shut off his view of what was behind it, was no place to choose for a midday rest.

All this time I waited patiently; interested, to be sure, but I should have been vastly more so if the lordly old fellow had turned my way. This I expected him to do when he got tired of loafing. Instead, he deliberately walked into the tall ranks of the marsh, which extended riverward for half a mile. At that maneuver of his I hurried forward, hoping to flush him on the margin; but he had vanished for that day. But though he had escaped me, the sight of him had made me keen to follow him even to that last hour when he should be obliged to accompany me home.

Just as I was turning away from the marsh, I heard a turkey-call from the shelter of a big live oak beside the old chimney. My heart told me that the caller was Dade Saunders and that he was after my turkey. I walked over to where he was making his box-call plead musically. Dade expressed no surprise upon seeing me. We greeted each other as two hunters who, being not over-friendly, greet when they find themselves after the same game.

“I seen the tracks of his number 9’s,” said Dade. “I believe he limps in the one foot since I shot him last Sunday will be a week.”

“He must be a big bird,” was my comment. “You were lucky to have a shot.”

Dade’s eyes became hungrily bright. The great gobbler was even then in his mind’s vision.

“He’s the biggest in all this country, and I’m a-going to get him yet. You jest watch me.”

“I suppose you will, Dade. You are certainly the best turkey-hunter of these parts.”

My hope was to make him over-confident; and praise is a fearful corrupter of mankind. It is not unlikely to make a hunter miss a shot. I remember a sportsman friend of mine once laughingly said: “If a man tells me I am a good shot, I will miss my next chance, as sure as guns; but if he cusses me and tells me that I am not worth a darn, then watch me shoot!”

For the time Dade Saunders and I parted. I walked off toward the marsh, whistling an old song. The sound of this tune was to make the old gobbler put a little more distance between himself and the poacher. Besides, I could feel that it was right of me to do this; for while I was on my own land my visitor was trespassing. I hung around the marsh-edges and the scrub oak thickets for a while; but no gun spoke out. The silence indicated that the old gobbler’s intelligence plus my whistling game had “foiled the relentless” Dade. It was the week later when the three of us met again.

Not far from the peanut-field there is a plantation corner. Now, most plantation corners are graveyards; that is, cemeteries of the old days where slaves were buried. Occasionally now someone is buried, but through the jungle-like growths pathways have to be cut to enable the cortège to enter. Such a place is the wildest wilderness. Here grow towering pines, mournful and moss-draped. Here are great hollies, canopied with the running vines of the yellow jasmine; here are thickets of myrtle, sweet gum, young pines and sparkleberries. If a covey of quail goes into such a place, you might just as well whistle off your dog, for both you and he may get lost in there while trying to find the birds.

Here, because in such a place they can hide from the heat and from the gauze-winged flies, deer love to come in the summer. In the winter, such a place on a plantation is a haunt for woodcock, an excellent range for wild turkeys (since here great live oaks shower down their sweet acorns) and a harbor for foxes and for other creatures of the general varmint type. Here in the great pines and oaks turkeys love to roost; such a place seems solitary, remote and detached from the life of the world. If the sun approaches setting, no man will be found near a graveyard of this mournful type. It was on the borders of just such a place that I roosted the splendid gobbler.

The sunset of a mid-December day glowed warmly. I had left the plantation house an hour before in order to stroll the roads through the shrubberies of the home tract, counting (as I always do) the number of deer and turkey tracks that have recently been made in the soft, damp sand. Coming at last near the dense corner I sat with my back against the bole of a monster pine. Aside from the pleasure of being a hunter there is a delight in being a mere watcher in the wild woods.

About 200 yards away, on a gentle rise in the pine lands, there was a little sunny hill grown to scrub oaks. Their standing sparsely enabled me clearly to see what I now beheld. Into my vision, with the long, level rays of the sinking sun gleaming softly on the bronze of his neck and shoulders, the great gobbler stepped with superb beauty. Though he deigned to scratch once or twice in the leaves, and peck indifferently at what he thus uncovered, I well knew that he was bent on going to roost; for not only was it nearly his bedtime, but he appeared to be examining, with critical appraisal, every tall tree in his neighborhood.

In my sight he remained 10 minutes; then he stepped into a patch of gallberries. I sat where I was, in silence and in motionlessness, trying earnestly to imitate those lying in the ancient graves behind me. For five minutes the big bronzed bird of the pinelands kept me in suspense. Then he suddenly shot his great bulk into the air, beating his ponderous but graceful way into the huge pine that seemed to sentry that whole wild tract of woodland.

Marking with strained eyes every inch of his flight, I saw him when he came to the limb he had selected. He sailed up to it and alighted with much scraping of bark with his big and clumsy shoes. So there, outlined against the warm colors of that winter sunset sky, was my gobbler. It was hard, indeed, to take my sight from him; but I did so in order to get my bearings in relation to his position. His flight had brought him somewhat nearer to me than he had been while on the ground. But he was still far out of gun range.

To see how I was going to maneuver to approach him, there was no use for me to look into the graveyard; for therein a man can hardly set a foot, and certainly in such thickets he cannot move without rivaling, by the conspicuous noise he makes, a wild bull of Bashan. Down the dim pineland road I therefore glanced. A moving object along its edge attracted my attention. It skulked. Like a ghostly thing it seemed to flit down from pine to pine. But despite my proximity to a cemetery, I knew that I was looking at no “hant.” It was Dade Saunders.

He, as well as I, had roosted the old gobbler, and he was trying to get up to him. Moreover, he was at least 50 yards closer to him than I was. Instinct told me to shout to him to get off my land; but then a better idea came. Quickly my turkey-call was brought into use.

As was intended, the first note was natural and good. An old hen-turkey was querulous. But then there came some heart-stilling squeaks and shrills. In the pinewood dusk two things were noticed: Dade’s making a furious gesture was one; the other was the old gobbler’s launching himself out from the pine, winging a lordly way far over the graveyard thicket and the lone wood beyond. I walked down slowly and peeringly to meet Dade.

“Your call’s broke,” he announced.

“What makes you think so?” I asked.

“Sounds awful funny to me,” he said; “more than likely it might scare a turkey. Seen him lately?” he asked.

“You are better at seeing that old bird than I am, Dade.”

Thus I put him off; and shortly thereafter we parted. He was sure that I had not seen the gobbler; and that suited me all right.

Then came the day of days. I was up at dawn, and when certain red lights between the stems of the pines announced daybreak I was at the far southern end of the plantation, on a road on either side of which were good turkey woods. I just had a notion that my gobbler might be found here, as he had of late taken to roosting in a tupelo swamp near the river and adjacent to these woodlands.

Where some lumbermen had cut away the big timber, sawing the huge short-leaf pines close to the ground, I took my stand (or my seat) on one of these big stumps. Before me was a tangle of undergrowth; but it was not very thick or high. It gave me the screen I wanted; but if my turkey came out through it, I could see to shoot.

It was just before sunrise when I began to call. It was a little early in the year to lure a solitary gobbler by a call; but otherwise the chance looked good. And I am vain enough to say that my willow box was not broken that morning. Yet it was not I but two Cooper’s hawks that got the old wily rascal excited.

They were circling high and crying shrilly over a certain stretch of deep woodland; and the gobbler, undoubtedly irritated by the sounds, or at least not to be outdone by two mere marauders on a domain that he felt to be his own, would gobble fiercely every time one of the hawks would cry. The hawks had their eyes on a building site; wherefore their excited maneuvering and shrilling continued; and as long as they kept up their screaming so long did the wild gobbler answer in rivalry or provoked superiority, until his wattles must have been fiery red and near to bursting.

I had an idea that the hawks were directing some of their crying at the turkey, in which case the performance was a genuine scolding match of the wilderness. And before it was over several gray squirrels had added to the already raucous debate their impatient, coughing barks. This business lasted nearly an hour, until the sun had begun to make the thickets “smoke off” their shining burden of morning dew.

I had let up on my calling for a while; but when the hawks had at last been silenced by distance, I began once more to plead. Had I had a gobbler call, the now enraged turkey would have come to me as straight as a surveyor runs a line. But I did my best with the one I had. I was answered by one short gobble, then by silence.

I laid down my call on the stump and took up my gun. It was in such a position that I could shoot quickly without much further motion. It is a genuine feat to shoot a turkey on the ground after he has made you out. I felt that a great moment was coming.

But you know how hunter’s luck sometimes turns. Just as I thought it was about time for him to be in the pine thicket ahead of me, when, indeed, I thought I had heard his heavy but cautious step, from across the road, where lay the companion tract of turkey woods to the one I was in, came a delicately pleading call from a hen-turkey. The thing was irresistible to the gobbler; but I knew it to be Dade Saunders. What should I do?

At such a time a man has to use all the head work he has. And in hunting I had long since learned that that often means not to do a darn thing but to sit tight. All I did was to put my gun to my face. If the gobbler was going to Dade, he might pass me. I had started him coming; if Dade kept him going, he might run within hailing distance. Dade was farther back in the woods than I was. I waited.

No step was heard. No twig was snapped. But suddenly, 50 yards ahead of me, the great bird emerged from the thicket of pines. For an instant the sun gleamed on his royal plumage. My gun was on him, but the glint of the sun along the barrel dazzled me. I stayed my finger on the trigger. At that instant he made me out. What he did was smart. He made himself so small that I believed it to be a second turkey. Then he ran crouching through the vines and huckleberry bushes.

Four times I thought I had my gun on him, but his dodging was that of an expert. He was getting away. Moreover, he was making straight for Dade. There was a small gap in the bushes 60 yards from me off to my left. He had not yet crossed that. I threw my gun in the opening. In a moment he flashed into it running like a racehorse. I let him have it. And I saw him go down.

Five minutes later, when I had hung him on a scrub oak and was admiring the entire beauty of him, a knowing, catlike step sounded behind me.

“Well, sir,” said Dade, a generous admiration for the beauty of the great bird overcoming other less kindly emotions, “so you beat me to him.”

There was nothing for me to do but to agree. I then asked Dade to walk home with me so that we might weigh him. He carried the scales well down at the 25-pound mark. An extraordinary feature of his manly equipment was the presence of three separate beards, one beneath the other, no two connected. And his spurs were respectable rapiers.

“Dade,” I said, “what am I going to do with this gobbler? I am alone here on the plantation.”

The pine-land poacher did not solve my problem for me.

“I tell you,” said I, trying to forget the matter of the five velveted bucks, “some of the boys from down the river are going to come up on Sunday to see how he tastes. Will you join us?”

You know Dade Saunders’s answer; for when a hunter refuses an invitation to help eat a wild turkey, he can be sold to a circus.

This story originally appeared in the 1921 edition of Plantation Game Trails.