Assigned to cover a draw high on Old Smokies’ spine, Kephart kindled a thin fire between roots of a mountain oak that wasn’t warm enough to thaw his fingers and toes. Rifle across his lap, he listened for the dogs to bay, announcing they’d caught a black bear’s trail. Down the courses of Desolation and Defeat, up around Devil’s Race-path, across the mountains’ highest ridge and back again, his neighbors, lean and wiry as the hounds they chased, sought to drive a black bear into their writer-friend’s sights.

He settled into his stand that frigid dawn, convinced that the dogs, part Plott and otherwise cur, would roust a bear yet to den even this late in November, and that someone would make a killing shot. Then as now, Plott hounds were reputed to be the tops among bear-dog breeds in the southern Appalachians. They should be; Henry Plott, who’d settled soon after the Revolutionary War about 50 miles from where Kephart shivered, had bred into them the abilities to bring black bears to bay no matter what it took.

Brindle-coated and with piercing voice, Plotts stand about two feet at the shoulder and weigh around 50 pounds. Kep’s friends thought they weren’t staunch enough and favored hounds that were half Plott and half a “big furrin” cur. The crossbreeding produced dogs with the stamina to run all day through trackless laurel and rhododendron hells. The Plott hound is North Carolina’s state dog, and they’re as revered across the country as they are by that state’s bear hunters.

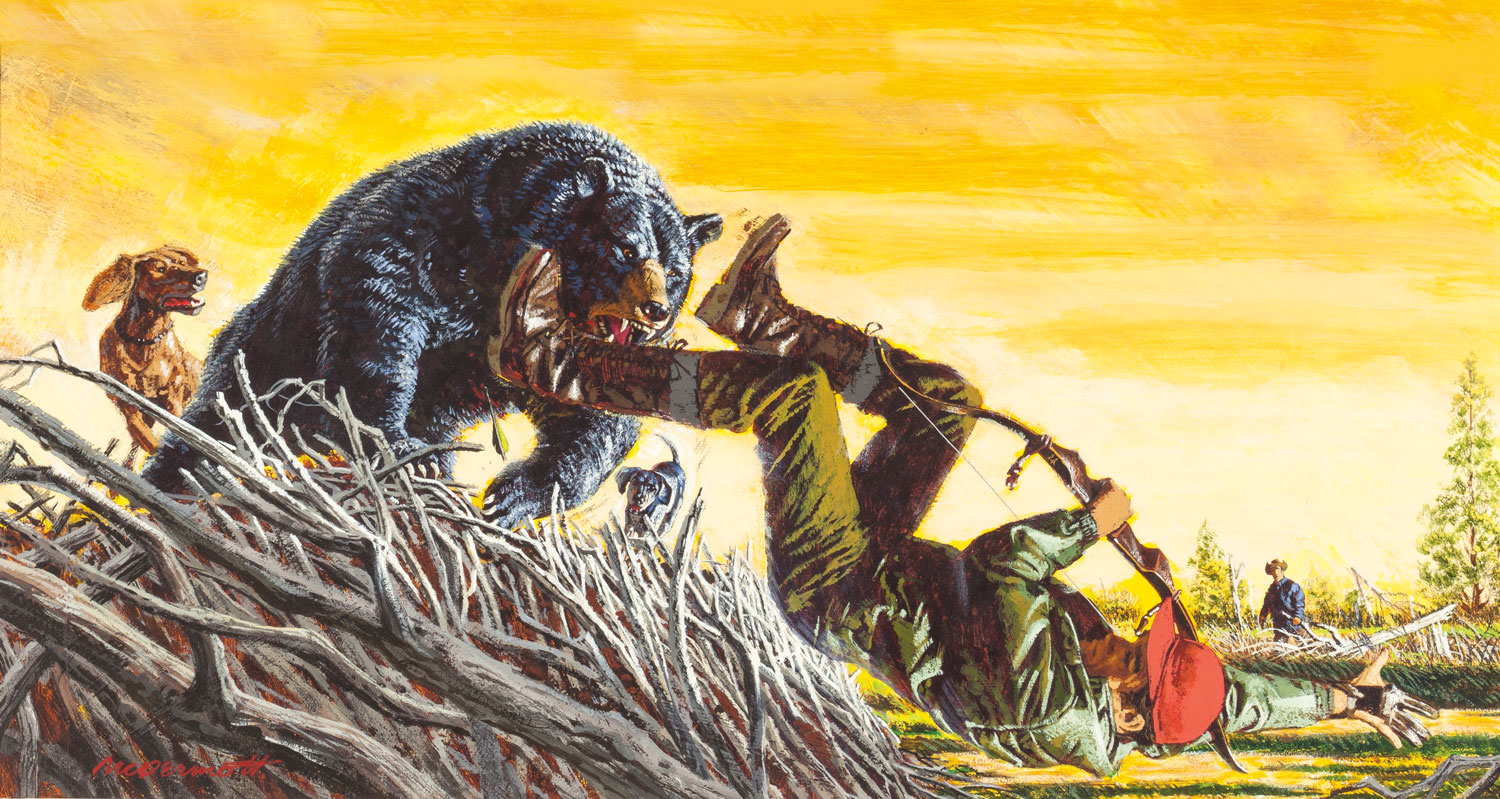

Bear Attack by John R. McDermott, Courtesy Heritage Auctions.

Anybody who’s walked Hazel Creek with fly rod at the ready has to admire every old gentleman who charged up steep, rocky slopes chasing their hounds. All those boys had to run on was a breakfast of fried fatback and cornmeal mush sweetened with a dollop of sorghum. They worked as hard as the dogs, something to keep in mind when hunting black bears in states where shooting over dogs is legal.

From one U.S. coast to the other and from Mexico into Alaska, black bears are found in all but a handful of states and most Canadian provinces. They rank among the most popular big-game species, and for good reason: Biologists estimate that 800,000 prowl the continent’s forests.

Denning up anywhere from early November to late December, depending on the severity of winter’s onset, sows give birth every two years in late January or early February and nurse their cubs—usually twins, sometimes triplets, and rarely as many as five. At birth, cubs weigh less than a pound; when they leave their dens in April, they’ll weigh four or five pounds, but occasionally twice that. They’ll continue to be nursed as they teethe and transition to solid foods. Usually they’ll return to hibernation with their mother before separating from her the following spring.

A 1920s’ hunter totes out a black bear he killed with his trusty Winchester. It wasn’t until the 1950s that the states began establishing hunting seasons for black bears.

Adult black bears are omnivorous to the umpteenth degree. Upon leaving their dens they focus on the tender buds of wild berries and other green shoots. The remainder of the year they feed on acorns and other mast, and come autumn, oats and corn before farmers have a chance to harvest them. As for meat, black bears prey on newborn livestock, fawns, and rodents, and will not pass up a chance to dine on carrion. Orchards attract bears just as they do deer. That local wineries and adjacent vineyards are springing up like weeds across the country must delight bears to no end.

Folks who live in bear country and leave garbage cans outside overnight are tendering an open invitation to a black bear, which, when habituated to human food, may bust through the kitchen screen door to steal dinner. Though it’s funny to see cubs lying on their back sucking nectar out of hummingbird feeders, humor flees when momma bear clamps down on that cute little family Fido barking in valiant but vain territorial defense.

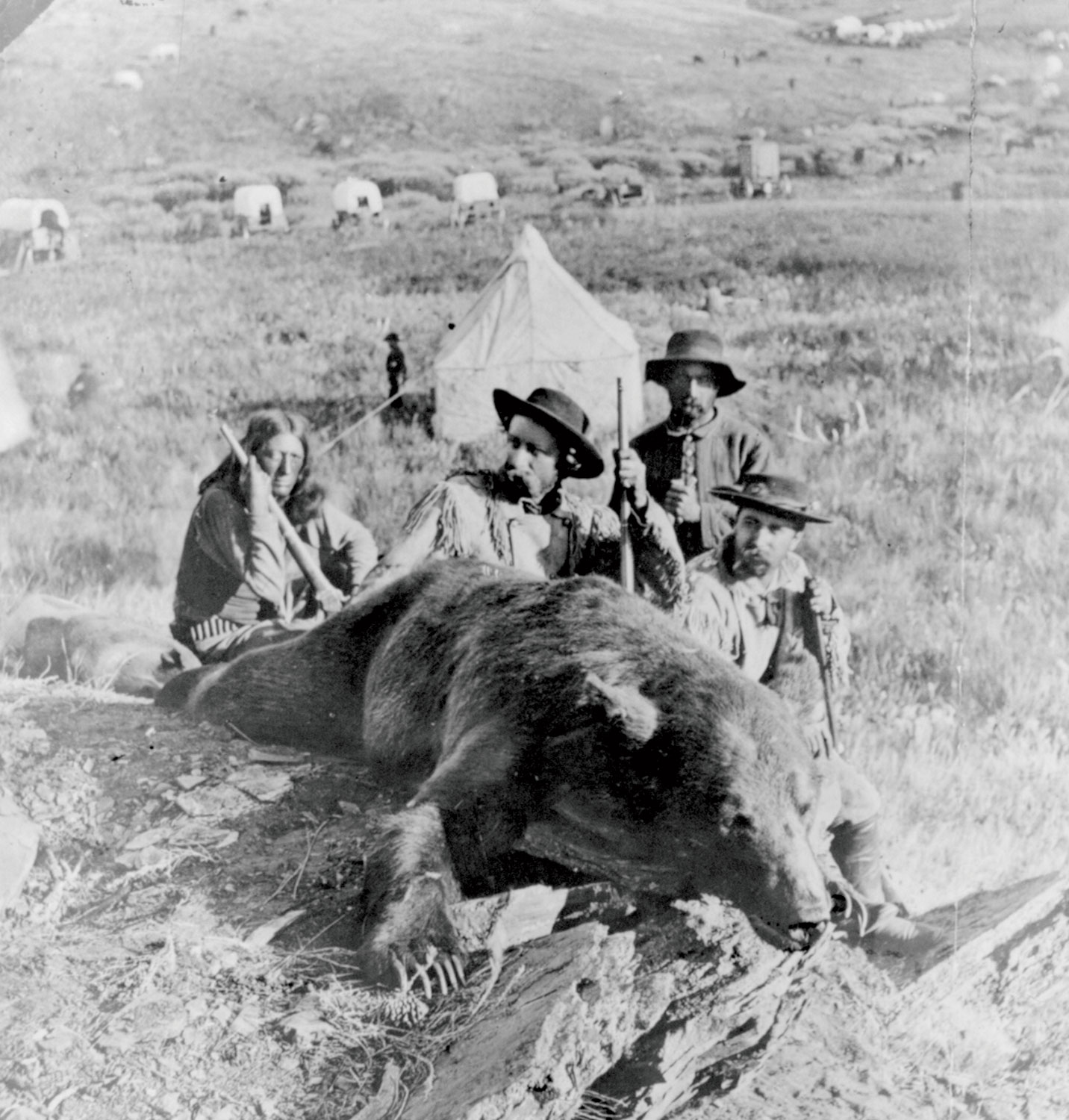

George Armstrong Custer poses with a black bear he killed in 1874 while on a hunting expedition in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

From the moment they came ashore, America’s pilgrims feared wild animals that fed on flesh. Perceived to threaten children, bears, wolves, and panthers ate livestock and pillaged crops. For nearly 200 years bears were considered predatory vermin that should be killed anywhere and anytime, and often for a bounty. Demand fed a thriving market for bearskin coats and rugs. During the same period the nation’s thirst for lumber and furniture stripped many forests, such as where Kephart sat, of mature trees and eliminated habitat essential for black bear survival.

By the early 1900s black bears were in trouble. With bears nearly extirpated in all states but those with the densest forests, conservationists began efforts to preserve them both. Black bears are icons for American wilderness. Naturally curious but wary of humans, they’re thought by many folks to be ferocious when cornered or when a sow with cubs is surprised. For this reason, campaigns were initiated to limit conflict between bears and humans.

Hunting was seen then, as now, as a viable tool for aligning bear populations with ecosystems that could sustain them. In the early 1950s bears began to be considered “big game,” and the first licenses to hunt them were subsequently issued. Today more than half of the states have established bear-hunting seasons.

When the federal government began acquiring the logged-over terrain that today constitutes the core of our national forests, it was mainly land that nobody wanted. The first forest reserves were created in 1891, an initiative that has grown into the U.S. Forest Service, which stewards 193 million acres of woodlands and grasslands. Much of that has regrown into prime habitat for bears, particularly in eastern states, where the big predators may live in relatively close proximity to major population centers.

Mike Pelton, the University of Tennessee professor emeritus who studied black bears in Great Smoky Mountain National Park for 32 years, believes that their population reached a “pivot point” in the late 1980s. Too many bears, he says, have resulted in more conflicts with humans.

Mike and I grew up in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the 1950s. If we wanted to see a bear, all we had to do was head for the Smokies 40 miles away. Almost any time we drove the sole transmountain highway from Gatlinburg to Cherokee, we’d see a black bear’s rump sticking out of a trash can. Foolish tourists would roll down their windows and feed them from their cars. Bears became fond of such curb service and would occasionally try to climb into vehicles, not, however, to say, “Thanks.”

In Knoxville these days you don’t have to drive to the mountains to see a bear. Like the sow and her three cubs spotted in East Knoxville last June, bears are entering cities searching for food. In Asheville, North Carolina, where I live, black bears amble through backyards; no bird feeder is safe. Researchers running the North Carolina Urban/Suburban Black Bear Study have set dozens of culvert traps in the city and its neighborhoods to better pattern bear behavior. Conflicts between bears and humans occur more than occasionally. Capturing and removing the bruins isn’t the answer. We’re surrounded by Pisgah National Forest, and a bear that’s been relocated will find its way back to town in a matter of days, so easy are the pickings in garbage cans and bird feeders.

Throughout New England, black bear populations are rebounding dramatically. In Massachusetts, for example, they’ve grown from 500 in 1985 to 4,500 in 2015. Even in Rhode Island, where black bears were thought to be extirpated, bear sightings are not all that unusual, and last year one was captured in Providence, the state capital.

Whether to legalize bear hunting or not is a thorny issue for states east of the Mississippi, but none more so than Florida. Since the 1970s the bear population in the Sunshine State has grown from a few hundred to an estimated 4,350 in 2016. In the past few years, the Florida Wildlife Commission (FWC) fielded roughly 21,000 calls concerning the bruins and handled 700 conflicts. After decades of on-again, off-again legal hunts, mostly on a county-by-county basis, all bear hunting was stopped in 1994.

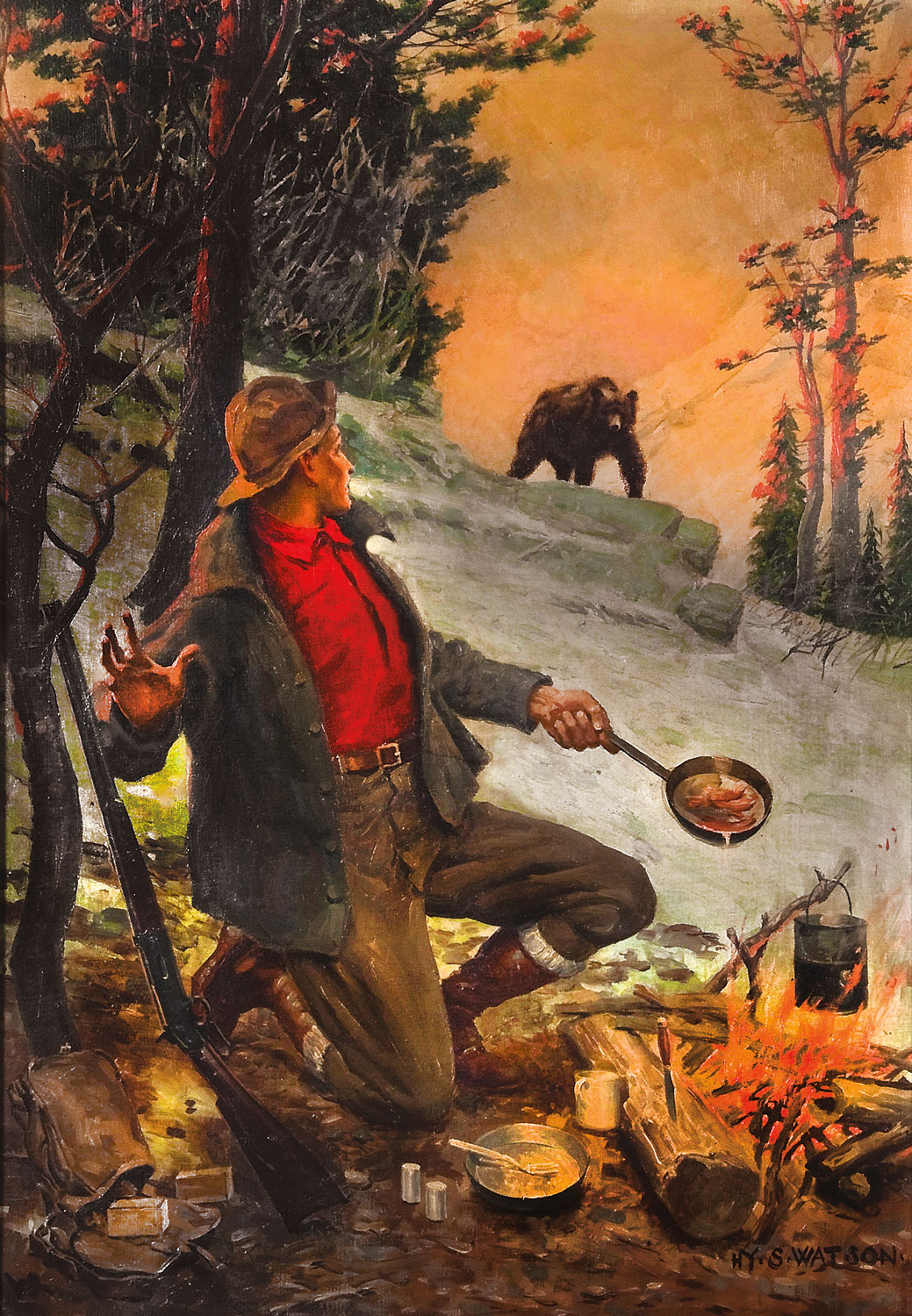

Oil painting by Henry Sumner Watson.

A full 20 years of study brought the state to the position of creating seven bear-management districts and, in 2015, holding a seven-day season in four of them. The season opened on October 24 and was shut down a day later in districts covering the panhandle and central parts of the state because harvest goals had been greatly exceeded. The following day the two remaining districts were closed. When FWC opened the season, it projected that roughly 10 percent of the estimated 3,150 bears would be taken. Three days into the season, 304 bears had been tagged. Florida then cancelled its proposed season for 2016, and whether a hunt will be held this year is in doubt.

Reacting to critics of the Florida hunt, Richard Corbett, former head of FWC, was quoted in the Washington Post as saying, “Those people don’t know what they’re talking about. Most of those people have never been in the woods. They think we’re talking about teddy bears: ‘Oh Lord, don’t hurt my little teddy bear!’ Well, these bears are dangerous.”

“As our population becomes more urbanized, Americans will lose their cultural memory of bears as wild predators,” says Jerry Apker of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources. Citizen-education campaigns are flourishing in Colorado and other western states, and across Canada, where bear hunting is deeply ingrained in the culture.

Black bear hunts are among the least-expensive of big-game hunts. Jim McCarthy of McCarthy Adventures offers hunts in the Canadian maritime provinces that cost less than $2,000. Most are over bait.

When I was writing a guide to North America’s greatest big-game lodges with Jay Cassell, then of Sports Afield, I was concerned about the ethics of shooting bears freshly emerged from hibernation that were bellying up to barrels of stale donuts, so I decided to book a spring hunt in central Quebec on Reservoir Gouin. The flight to the outfitter from Montreal crossed miles and miles of managed forest. Some plots were clearcut and covered with low brush. Others were studded with ten-foot trees, while orderly rows of trees appeared ready to harvest on some.

The outfitter told me he had exclusive rights to take ten percent of the bears in his district. He wanted me to shoot a young bear, which he would have mounted and take to outdoor shows in the East where he recruited clients.

On my first morning I sat leaning back against a spruce watching the bait. After a couple hours a small bear sauntered in and stretched up to the top of the barrel. He was just what the outfitter had ordered. One shot from my .30-06 killed it. Shooting groundhogs at 200 yards was exponentially more challenging. Hunting bears over bait was not my cup of tea.

In camp, though, were a husband and wife. A few years earlier, while hunting with this outfitter, he had taken a lovely 400-pounder. His wife wanted one just like it. Day after sometimes drizzly day they sat and watched a bait and fought blackflies. Finally she shot her trophy. I’ve never seen two happier hunters. Hunting over bait may be the surest way to nail the black bear of your dreams. It certainly results in fewer wounded bruins.

Red Flannel Swing by Walter Martin Baumhofer.

As I look back on that hunt, I remember thinking about what I’d do if a hungry bear approached the bait from behind me. Was I more appealing than a stale donut? From where I sat, could I whirl around quickly enough to deliver that fast first shot necessary to put the bear down? I didn’t know . . . and still don’t.

The odds of being killed by a black bear are even less than being struck by lightning. But bear attacks have occurred, some with deadly outcomes.

Darsh Patel, a 22-year-old Rutgers student, was hiking with four friends in Apshawa Preserve in New Jersey’s north-central highlands when they were warned by a couple coming down the trail that they’d seen a bear. The five continued on, encountered the bear, and attempted to retreat slowly back down the path. When it ambled after them, they began to run. Fleeing, Patel lost a shoe and climbed a boulder, where the bear caught and ate him.

Lessons: Though they can seem as curious as black Lab puppies at times, bears are wild, eat meat, and had best be given a wide berth. Second: Never, ever run from a black bear. That may trigger an assault, and they can run twice as fast as we can. Third, Lynn Rogers of the North American Bear Center, who has spent 50 years studying black bears in northern Minnesota, recommends carrying Halt, a liquid repellant for vicious dogs. One squirt in a bear’s eyes sends it fleeing, with no risk that the spray will blow back in your face. Fourth, pack food in bear-proof containers. Toiletries such as toothpaste should be stored with food, not kept in your tent.

As I sat in those woods in Quebec overlooking that tub of far-past-their-prime pastries, I had no idea whether the bear that came to breakfast was male or female. My ignorance was my fault; I simply hadn’t given the matter any thought. I should have. The bear I killed was small, just what the outfitter wanted to stuff for his booth at outdoor shows. The average weight of a sow in Refuge Pageau in western Quebec is about 165 pounds, while boars easily exceed 300 pounds. The bear I shot weighed about 150 pounds. In retrospect, it’s highly likely that it was a sow, and that her cubs, freshly out of the den, were nearby. Only now am I aware, thanks to Rogers’ research, of the fate that awaited her offspring: certain death.

Collateral cub mortality is taken into consideration when bear biologists recommend spring hunting seasons. In a similar vein, it’s also a factor in decisions to legalize training bear hounds in the spring. When they chase lactating sows, they separate them from their cubs, with which they may not reunite.

In many ways, sitting on Old Smokies’ top like Kephart did listening to hounds course a bear is closely akin to the joy inherent in following any dog that’s working game. It’s certainly the most exciting way to hunt black bears.

For a while, when clearcutting was rampant on Victoria Island in British Columbia, outfitter Jim Shockey, host of the Outdoor Channel’s TV show that carries his name, could hike clients up a high ridge, glass newly harvested forests thick with salal and other spring berries, spot a record-book-worthy black bear, and stalk it. Alas, the days of clearcut timber harvesting are largely past, and the areas where Shockey hunted are now blanketed with adolescent trees.

Still-hunting, that is, sitting and overlooking a small plot from which timber was cut a year or two ago and where berries flourish, is probably the most effective way of bagging a trophy black bear. One Minnesota hunter I know has been very successful at killing bears feeding in oat fields.

Perhaps the ultimate black-bear-hunting challenge can be found not in besting Boone & Crockett’s current world record—skull measurement of 2211/16 inches, taken by Duane Helland in Chippewa County, Wisconsin, in 2003—but in collecting a “grand slam.”

Alhough black bears are typically black east of the Mississippi, fully 80 percent of the black bears in Colorado sport coats colored blond, bluish-grey, brown, or cinnamon. Smaller populations of color-phase bears roam western states and Alaska. There’s even a population of white bears, which are illegal to hunt. Known as Kermode, or “spirit bears,” they’re found on islands off the coast of British Columbia.

Time may be running out to harvest a bear with a coat of silver-tipped guard hairs that appears bluish-grey. Found in southwestern Alaska, these bears—Ursus americanus emmonsii—inhabit pockets isolated by intermontane ice sheets, hence their common name: “glacier bears.” Melting of the glaciers is allowing these unique bruins to range more widely and mate with other bears with dominant genes that produce black coats. The era of glacier bears may well be closing.

No matter which color phase it comes in, meat from black bears should not be struck from the menu. Rolled in a dry rub and grilled over charcoal, the backstrap from my young bear tasted as good as any pork tenderloin. Many hunters have their bear meat made into sausage or bologna. Recipes for bear stew abound. Decant a bottle of Shiraz with stout heart, serve, and enjoy.

ALASKA BEARS: Stirred and Shaken is a collection of 24 stories describing Jake’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska.