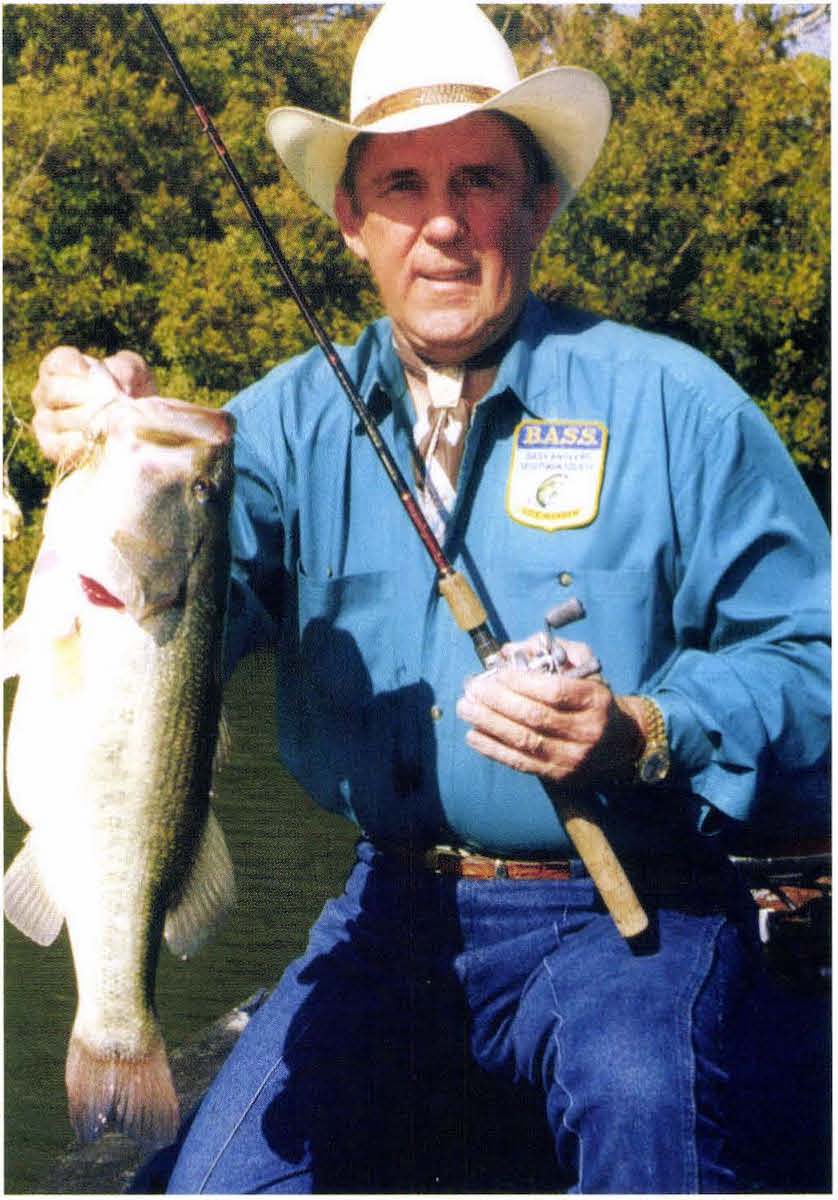

The man was Ray Scott, an outdoors entrepreneur who turned his love of bass fishing into a successful international enterprise. His primary tools in building his dream were simply imagination, enthusiasm and a pleasant way with people. As Robert Boyle wrote in Sports Illustrated in 1969, shortly after Scott established his Bass Anglers Sportsman Society (B.A.S.S.), “(Scott) has a silver tongue and a golden touch.”

There’s not a braggartly bone in his body. He just tells it like it is, with down home Alabama humility and the enthusiasm of a boy who just caught his first largemouth.

”I’ve been a bass fisherman since I was seven years old,” begins Scott, “and that was purely by accident. I was fishing for bluegills in a little pond and caught a huge bass… about seven or eight inches long. Well, that got me hooked and I never quite got over it.

“Fish are so interesting, and certainly the pursuit of fish is interesting. There’s really nothing boring about bass fishing, if you really pursue it with an open mind and determination.”

“Fish are so interesting, and certainly the pursuit of fish is interesting. There’s really nothing boring about bass fishing, if you really pursue it with an open mind and determination.”

Ray went into the insurance business after college, but kept fishing for bass whenever possible, carrying his tackle along wherever business took him.

“That was a great business to be in because if you didn’t want to work, you could go fishing.”

Ray did very well in the insurance business, traveling the four states of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Arkansas. On one particular trip to Mississippi, Scott was trying to wrap up his work week close to a good fishing hole.

“It was around Jackson on a Friday in 1967. I put my suitcase away in the hotel and a buddy and I went fishing. Had a lousy day. The weather was crazy … we just didn’t do well at all.

“So my buddy dropped me off back at the Ramada Inn and said he’d be back later to get something to eat. I took a hot shower and then settled back on the bed with the TV on.

“It was basketball season – nothing else on. I was just lying there watching it, and thinking, when it occurred to me – I don ‘t know why but I’m going to blame it on God – something said to me, ‘ I need to have a tournament. A bass-fishing tournament. Get people to come in and pay all entry fee and find out who’s good! ‘

“This all happened in a matter of seconds and I remember standing up on the bed and my head was about six inches from the ceiling. I was snapping my fingers and saying, ‘By golly, I’m going to make this thing work! ‘”

Scott firmly believed there were enough avid bass fisherman out there to support tournaments. By the time his buddy came to take him to dinner, Scott has already decided he’d hold the first tournament at Beaver Lake in northwest Arkansas. His buddy later told friends Scott had ‘gone nuts.’

Scott left Mississippi the following Sunday and headed up to Little Rock. Determined to find the stronghold of decision-makers for the goings-on at Beaver Lake, he located the state wildlife office and was told that most landings, bait shops and such were divided between two municipalities – Rodgers and Springdale.

“I called the Rodgers Chamber first and asked to speak to the bossman. I said ‘my name is Ray Scott, I’m the head man of the All-American Invitational Bass Tournament.’ I just made up that name.

“So she puts me on with the boss of the chamber there and he proceeds to tell me that he’s about to quit his job and won’t be getting involved with me.”

Scott then called Springdale and was connected with the director of their chamber, Lee Zachary.

“Yes sir, Mr. Scott,” Zachary said, “I’ve heard of you and your fine organization.” Scott laughs as his recalls this conversation. He drove up to Springdale that evening, met with Zachary and a few of the lakeside business owners, and a few hours later his first bass tournament , was born.

“That June fifth, sixth and seventh, I had a hundred-and-six men show up, paying a hundred-dollar entry fee, which was a lot of money back in 1967. It was a success and I committed to doing a second tournament there. The rest is history.”

Along with the tournament, Scott was in the process of forming the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society, or B.A.S.S. After the first year’s effort, Scott’s organization had more than 2,000 members; the following year, membership soared to nearly 25,000.

In 1969, haunted by the memory of the contaminated waste that seeped unchecked into the Alabama River near his childhood home, Scott harnessed the resources of B.A.S.S. to sue several companies responsible for the pollution. His litigation was successful in most cases and the river was rescued. During the next two years, B.A.S.S. filed more than 200 lawsuits in Alabama, Texas and Tennessee, establishing itself as an active, take-no-prisoners member of the environmental movement.

“Teaching fishing and preaching anti-pollution” is the way Scott describes the organization’s early mission. Along the way, more than 3,000 local clubs were created.

Several years ago, Scott introduced another pro-conservation effort that was as foreign to bass fishermen as trolling with squid.

“I believe it was 1969 when I got a call from a man named Al Ellis who asked if I would speak at a meeting of the Federation of Fly Fishermen in Colorado. He said they’d get me a room, food and take me fishing.

“They called it a river, but you could throw a rock across it. Six or seven of us were lined up with our fly rods and nothing happened for about an hour. All of a sudden on the far end down there, this fella made a sound I’d never heard. A ‘fly fisherman’ sound I suppose. (Chuckle) ‘Yeehah! ‘ or something like that.

“Everybody dropped their poles to go watch him fight this fish. After a minute he pulled his net off the back of his waders and scooped this fish up. I promise you, that fish might have been ten, eleven inches long. Looked like a big cigar. I’d never seen such a ceremony in all my life. He took some little pliers from his vest and removed the fly. And all these guys are standing around watching him.

“Then he took the trout and put it back in the water, and it swam out of his hand like a flash. I saw six grown men having absolute fits when he released that fish. High fives the whole deal. I’m thinking to myself, ‘Lord God, if they have such a thrill out of that tiny little trout, I wonder what they’d do with a five- or ten-pound bass. That was the moment I had the idea to go back home and find a way to start saving all these fish we’d been killing.”

Later that year, at a tournament at Table Rock Lake in Arkansas, Scott addressed 130 or so members of the bass fishing tournament trail.

“Boys, I want y’all to listen to me. During these tournaments we are killing too many fish. At our next tournament this coming March, I want y’all to make an effort to keep these fish alive.”

There were no built-in “live wells,” so a fisherman had to use his imagination – usually a big cooler and a coffee can to continually refresh it with oxygenated water.

“After the tournament, I wrote them all a letter thanking them for their efforts,” Scott recalls. “I told them that at the next tournament, for every fish that lives and can swim off, I would give them a one-ounce credit on their score. Well, you’d think I’d given them a hundred-dollar bill. It really caught on and the whole catch-and-release tournament really was born. Heck, we have people fishing in tournaments now who’ve never killed a bass.”

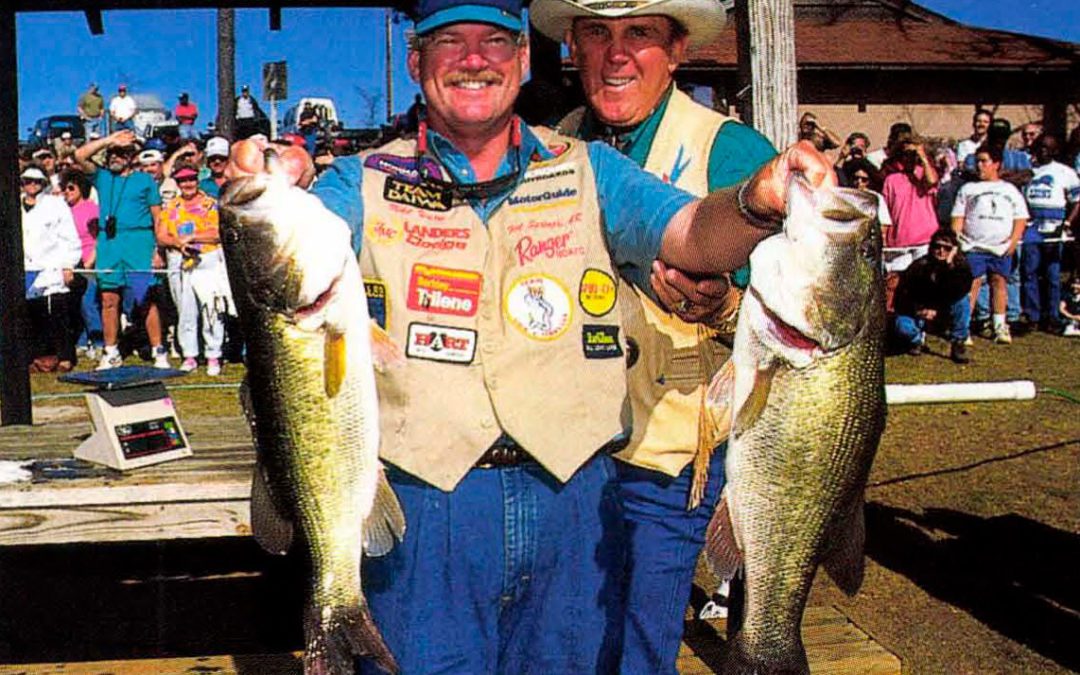

Shortly after catch-and-release took hold, Scott got together with the Ranger Boat Company to create the first built-in live wells. Today, Scott estimates that the tournaments are releasing well over 95 percent of the bass caught.

“And what’s really nice is that a fisherman – you know, Joe Blow who works a lot, but slips off in his boat now and then – he catches a nice two and one-half-pound bass. Well, he looks at the fish, and it’s his fish. He can take it home, or fillet it, whatever he wants to do. But because of the influence he’s felt over the years, he leans over, nobody in the boat with him, and he releases that fish, and it swims off into the darkness.”

Scott is justifiably proud of what he’s accomplished, saving bass and protecting the waters they inhabit being his most lasting achievements.

Ray Scott has received dozens of awards recognizing his entrepreneurial spirit and devotion to conservation. Here are just a few:

- 1979 Public Service Commendation, U.S. Coast Guard. For furthering Coast Guard aims and boating safety.

- 1987 National Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame.

- 1988 Sport Fisherman of the Year. Sport Fishing Institute.

- 1994 International Game Fish Association Conservation Award. The first Conservation Award presented by IGFA.

- 1995 Field & Stream’s “Twenty Who Made A Difference.” Named as one of the 20 individuals who have done the most to influence the outdoor sports in the past century.

- 2002 Inducted into National Boating Safety Hall of Fame

- 2003 First Alabamian inductee into the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans.

- 2004 Inducted into International Game Fish Association Hall of Fame

- 2005 Field & Stream’s “Legends of Fishing.” Entered into Field & Stream’s “fishing hall of fame” as one of the 50 all-time great fishermen who have made a major impact on the sport of angling.

- 2006 Budweiser Conservationist of the Year – named one of the 20 greatest outdoor Americans of the 20th century.

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish.

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish.

Read on as some of the sport’s most talented writers recount their personal memories of catching bass, trout, bluefish marlin, tuna, and more. Explore the Pacific with Zane Grey, as he fights a 1,000-pound blue marlin, or listen as A.J. McClane explains just what it really means to be an angler. Take a step back in time when you read Ernie Schwiebert’s tale of fishing a remote lake in Michigan, when he was still only a young boy. Each of these stories, selected because of its intrinsic literary worth, reinforces the unique personal connection that fishing creates between people and nature. Buy Now