The comeback story of one of the most unique antelope in the world

Mention Ethiopia to a westerner and images of drought and famine come to mind, an impoverished land wrapped in tragedy and sadness where pity is a leading export. Thus, imagine my surprise as I land in Addis Ababa to a bustling metropolis where the streets are full of vendors selling all manner of fruits, vegetables and knock-off Chinese goods. Thanks to sustained and massive United Nations investments in Ethiopia—including locating the headquarters of the UN’s Economic Commission for Africa in Addis—the country is turning the corner to a new reality if not prosperity.

As surprisingly impressive as Addis strikes me, I did not travel across the globe to spend time in an African city. Instead, my destination is the 9,000-foot highland cloud forest south of the city and one of the rarest and most singularly spectacular animals in the world—the 500-pound mountain nyala with its blue-gray spotted coat and white chevron markings. I’m here researching a book about sustainable conservation models being employed across the globe, and the tale of the mountain nyala is an especially intriguing one.

They occupy a very limited range and these forests with their tentacled hardwoods and abundance of game are prized for their food and fiber by an ever-expanding human population that is continually encroaching, making mountain nyala conservation an ongoing tug of war between human and animal interests. It is the money paid by mountain nyala hunters—a single hunt surpasses the cost of many Americans’ first homes—that provides the leverage to fend off development in this stretch of the country. The Ethiopian government allows hunters to take fewer than 20 of the animals each year as part of what is a highly regulated conservation plan. Without the revenue generated by the sale of these hunts, however, there would be little economic reason to protect the habitat the mountain nyala—and scores of other species—depend on for their very survival.

The stunningly beautiful mountain nyala and its habitat have been protected thanks in large part to the efforts of the Roussos family with support from hunters across the globe. Photo courtesy of Jason Roussos.

No one understands the universal conservation axiom, “wildlife that pays, stays,” better than the Roussos family. Nassos Roussos, a 74-year-old son of Greek immigrants, founded a hunting company called Ethiopian Rift Valley Safaris in 1981 and became an unofficial ambassador of sorts for the mountain nyala and its specialized habitat. He is the nyala’s Lorax, the Dr. Seuss character who speaks for the trees. In this case, he talks for both the trees and nyala.

“Wildlife in Africa is viewed by locals the same way a rancher sees a steer,” says Roussos. “Once the last nyala, forest hog and bushbuck is snared from the forest, the land will be surrendered to the ax and plow, never to exist as wildlife habitat again.”

After decades of fighting to protect nyala habitat, the elder Roussos passed the conservation torch to his son, Jason. He’s a 40-year-old Colorado State University trained biologist—class of 2000—who is a kind of bush baby who grew up in the wilds of Ethiopia learning the ways of the forest like a modern Tarzan. Hear him mimic the sounds of the colobus monkey or leopard and you quickly know he’s a product of his wild environment.

As both a hunter and biologist, he possesses a unique understanding of the interconnected relationships of plant and animal species and provides a sense of place at a level unmatched in my 40-plus forays into the African wilds producing television documentaries. I had known about Jason’s unique background having spoken to him in advance of my journey to Ethiopia in our mutual home state of Colorado—he being a seasonal resident and me full time.

As my charter plane lands on a crop duster strip surrounded by a mosaic of waist-high wheat fields interspersed between small villages, Jason and his Land Cruiser are waiting. It is a journey into the pages of National Geographic as scenes of horse-drawn carts, herders tending cattle, sheep and goats in and around villages of mud huts with thatched roofs surround us. The thorn-lined fields seem to have gone unchanged for centuries, as if the industrial revolution is a mere rumor here. As pieces of the planet go, the Highland Cloud Forest of Ethiopia’s Bale Mountains is as inviting as they come—a stunningly beautiful rain forest jungle. Driving from the lowland agricultural fields into the highlands and exchanging crops for hardwood forests is akin to leaving the Clovis while entering the Neolithic.

A colobus monkey leaps from branch to branch as the film crew arrives at Roussos’ highland camp. Photo courtesy of John Macgillivray, Dorsey Pictures.

As we enter the forest there are herders emerging from the trees with goats and mules, some loaded with fallen branches collected as a concession to the nearby village, a way to provide them needed fuel without cutting more trees. Deeper into the forest, we arrive at Jason’s camp, our base of operations from where we’ll launch forays farther into the forest to film the reclusive nyala.

We start early the next morning, loading up a Land Cruiser with several scouts armed with radios. About 20 minutes into our drive down a dirt track cut into the forest, Jason drops off a couple of the scouts who walk to an overlook where they’ll sit this morning. Meanwhile, we continue to our own perch on the edge of a sweeping valley. The idea is to wait with binoculars and cameras for the gray form of a mountain nyala to emerge from the green sea of the forest.

Cinematographer John MacGillivray (foreground) and Jason Roussos await the arrival of a mountain nyala amid the lush forest vegetation of Ethiopia’s Bale Mountains. Photo courtesy of John Macgillivray, Dorsey Pictures.

About two hours into our sit, Jason receives a faint radio call informing him that the scouts the next valley over have spotted an old bull. What ensues is a scramble to get there before the nyala disappears as they so often do like a puff of smoke. Heart pounding and legs burning from the mountain sprint, we crest the hill above the valley where the nyala had been spotted to witness the magnificent beast browsing amid the bushes some 200 yards away. Its unique hourglass horns and massive body make it seem as though it’s a relative of the unicorn, one of the rarest antelope in the world.

Witnessing one of the great beasts is nothing short of mesmerizing, an affirmation of the years spent by the Roussos family protecting these enchanted forests. With an ever-growing human population, however, Jason knows the fight is never over.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow Sporting Classics TV host Chris Dorsey at Forbes.

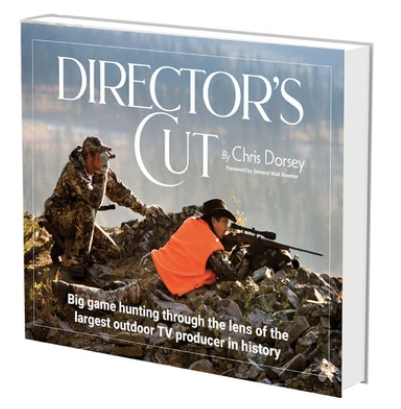

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

Dorsey has spent the past 25 years investigating and chronicling the animals, people and unforgettable places home to remarkable big game hunts while producing nearly 60 outdoor adventure television series. In the process, his teams amassed a library of more than 100,000 hours of HD footage and nearly 150,000 photographs, making Director’s Cut (the book and DVD) an unmatched celebration of the world of big game hunting. Buy Now