As the light turned to dark, a male leopard cautiously followed a well-worn path in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro. The cat had been here before, perhaps as recently as the previous night. As he slipped in and out of the long grass, the leopard passed the dimly glowing lights from a nearby manyatta (village), then continued on his seemingly purposeful mission, stopping frequently to sniff tracks and check out his surroundings with his superb nighttime vision.

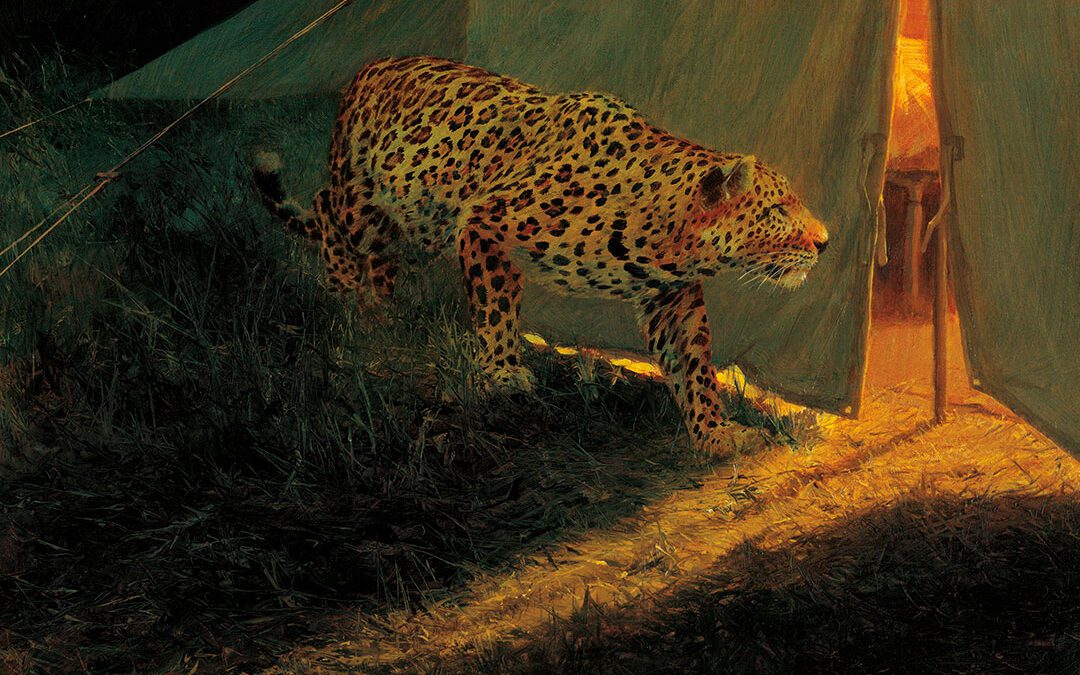

Native voices, possibly herdsmen, faded away as the leopard crept along, now closer to the ground. It stopped and crouched even lower, peering through the grass to watch the comings and goings of people in a tented camp. The big cat waited patiently until the strange voices were silent. Then, beneath a bright, cold Africa moon it started to sneak toward the camp.

The leopard approached one tent and circled it silently before its attention was drawn to another. Still creeping low and undeterred by the flickering light of the campfires, it picked up its pace and, with the brazen audacity common only to leopards, it rushed through the open flap of the tent and in a flash, stole away with its chosen prey.

The year was 1903; the place was German East Africa (later Tanganyika, now Tanzania). The camp was that of two hunters: Kalman Kittenberger, a young Austro-Hungarian sporting gentleman, and an old African military man, a corporal at the Moshi Garrison.

The men, who had pitched their tents about 100 yards apart, had arrived to hunt elephants in the area, which was soon to be a protected reserve. Their tents were pitched adjacent to two separate trails that each hunter would scout separately the next day.

That night Kalman had visited the old African’s tent and had drank and talked well into the wee hours. The old African owned a bulldog named Simba, perhaps for its tenacity, but a strange choice of dog in this climate. The breed’s short nose and breathing passage makes it hard for the dogs to stay cool, and it would probably have had suffered much discomfort in the days to come. The bulldog is also prone to suffering from heatstroke. But the old African loved his dog and it went everywhere with him, usually sleeping under his bed. On this night, however, his loyal companion was snatched from beneath him with unbelievable speed by the marauding leopard.

The African wasted no time in grabbing his 7mm Mauser and firing at the fleeing cat. The commotion brought his colleague rushing from his tent and the two hunters fired in the general direction of the escaping leopard.

Everything was silent as the hunters followed the predator into the inky blackness. Unlike lions, leopards have a habit of doubling back and attacking their pursuers at incredible speed. Knowing this, the two men proceeded with extreme caution, their eyes gradually adjusting to the dark. Intermittent clouds obscured the moonlight, making their task even more difficult. Listening for the leopard’s distinctive cough or the dog to whimper, the two men moved silently through the long grass. The only sound was from their pounding hearts.

After a short time the hunters stumbled across the dog’s body. Their shots had apparently missed, but at least they forced the cat to drop poor Simba. Like a ghost, the leopard had escaped to live and maraud another day.

There were many stories of man-eaters prior to World War I in East Africa, but lions weren’t always to blame. Leopards were, in fact, the bigger culprits, and stories such as this were not uncommon. Cattle and other livestock were in particular danger, but unbeknownst to most Europeans at the time, leopards also accounted for many human injuries and deaths. But their favorite prey was the dog. They snatched them from camps and villages, sometimes in broad daylight right in front of their masters. One has to realize that leopards were far more common than lions; indeed, they could be found almost everywhere on the African continent, but because of their secretiveness, they were seldom seen.