Had a man once who said, “The older the boy, the younger the man.” Strikes me he was right. No matter how old you are, you got to hang on to him—the boy—never let him go.

Hardly back from Chile and Patagonia, languishing in a chair before the fire—even as the wheelstones of your mind still mill the bespeckled brown and rainbow grist of thrills that could for most folks satisfy the longing of a lifetime—how is it possible to feel that somewhere at the tap root of your soul something remains unfulfilled?

Or perhaps from battles with the acrobatic, chromium aerialists of the Caribbean? Or the silver kings of the Alaskan Bays? Or the multi-splendored sails of the Panamanian Pacific? And yet somehow down really deep, where the well springs, to still feel a little sunfish beckoning from long ago that yearns to be complete?

Maybe it’s just me. I guess it takes a tortured and beleaguered man. One that’s lived past 50 maybe and crossed the horizon into the second half of his century. Seen the landscape on the far side and wishes some days he could know a place again like the one once he left.

Can’t help but wonder if you ever feel the same way? If you want some days more’n’ anything—at least once a year—to find the way back home, and consider if you still can? I mean, really home. Find again the way you felt, near where you started? Before all the miles and years, and continents and cravings? Back when you could be content the day long with a nickel in your pocket, a hank of waxed thread, a linament bottle corkstopper and a bent pin?

Well, like I said, maybe it’s just me.

Besides, it’s early in the year to be quite home. Some time yet before the beckoning will grow stronger. There’s still the dogs, and bird season to see through. Redbud and dogwood blossoms. Turkey time to suffer and hopefully survive, right down to the last 3 a.m. and pre-dawn gobble, just to fool close the man that made it. Before, if you persevere, spring ripens, all balmy, sun-spackled and green. There’s the shad run on the river, partridge a-drummin’ in the hills, bass in the sun-warmed shallows, apples blossoming, that fair, sweet air on tender breezes that smells like the warm, setting sun on Mary Ann Richards’ neck at the junior prom, so you know again the bream are on the beds.

From every roadside puddle, the peepers are still going strong, joined now at twilight by the yeee-annks of the toads, the fever-pitched sawing of the cicadas and the eerie flutter of lovelorn screech owls.

April sprinkles past, explosively gay and green, and then the Earth is pregnant with May, all heady with the buzz of bees, a fresh mayfly hatch, the first spotted fawns in the meadows, molly-pops in the pastures and the love song of a distant bobwhite in the fence corner, the one that still borders the gardens of your memory.

It’s right about then that the longing really begins to swell. So that you ain’t really caring you’re not off helicoptering to some rush of water you can’t readily pronounce in Russian, or gone quite yet to some place halfway around the world called Zanzibar, rich with rosary pea and marlin. They can wait a bit. It’s not the train headed north anymore, but right then the train smoking south you want to tag onto.

“Do you he-a-r-r that lon’-som’ whip-p-’r-will . . .” Sing it, Hank.

Homeward bound. Down home. If just the once in a year…really home. So, no matter where you may keep them stuck away in the 21st C, I’ll bet you still have some, and in your head it’s the same as going to the chimney corner of the old home place long ago, where the bees bored holes in the mud between the stones and left you a hide for your Indian money.

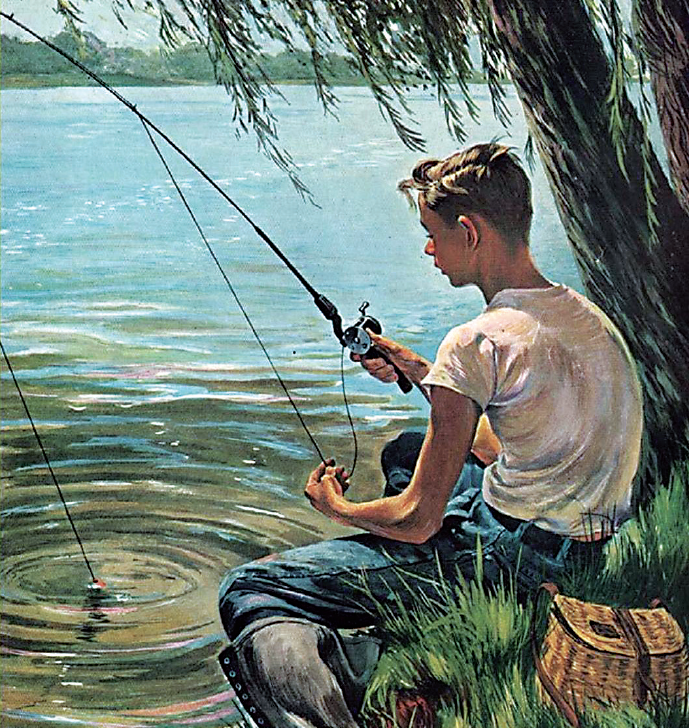

Though more importantly, created the nook where the cane poles always stood. Rigged and ready. Before you make an imaginary stop by the chicken lot, to scratch out a few worms to carry in the gummy black dirt of an old tin can. Which ain’t altogether that easy to come by anymore, coffee-size. It just ain’t too romantic that you had to buy ’em in a plastic cup from the bait shop, and much more convenient to the purpose to just forget.

’Cause it’s off and away now—can’t wait no longer— down through the lush June-green grass of the hillside pasture, where Maggie, Granny’s Jersey cow, once bucolically grazed, through splashes of goldenrod and spikes of purple thistle, past Methuselah, the rambling old scuppernong vine a double-century along, wobbling atop splayed cedar legs, to the “fishin’ hole,” that you couldn’t see the bottom of, below the old rock dam on Taylor’s Creek.

I did early last summer, you know. Drove anxious hours to get there one day, when the urge got so strong I couldn’t stand it anymore, got there ’bout noon and gained permission from a man to seek out the farm. It was grown up some, with blackberry vines, ragweed, sedge and honeysuckle. We don’t own it anymore. Our family of then gone now, all…farming Elysian fields:

I did early last summer, you know. Drove anxious hours to get there one day, when the urge got so strong I couldn’t stand it anymore, got there ’bout noon and gained permission from a man to seek out the farm. It was grown up some, with blackberry vines, ragweed, sedge and honeysuckle. We don’t own it anymore. Our family of then gone now, all…farming Elysian fields:

Grandpa, Grandma, Daddy and Mama and Uncle Wade, Aunt Rachel and Aunt Martha, and Uncle Sidney and Aunt Louise, Uncle Manly and Aunt May and Uncle Billy, and the kith-and-kin of us kids that came with the package, to grow up and be educated in the woods and on the creeks of Cedar Grove.

But the remains of the old house place were still there. That day, them too. Even in one corner of the old, broken-down porch, the weathered and splintered wooden tub and rusted hand-crank still, of the old ice-cream freezer that turned many a cold and delightful, sugary gallon of Granny’s peach ice-cream on sweltery summer afternoons, every family Sunday.

The sun was warm and kind, doves cooed a welcome from the pines, and honeysuckle, yellow jasmine and lilac were on the air. I took off my shirt, shoes and socks, tossed them in the truck, rolled up my pants legs and went blissfully foot-naked. Crossed the old, gray, broken rail fence in the weeds, pole and worm can in hand, and headed off down through the pasture. The green grass still felt old-timey soft and cool under my feet, and I stomped a Devil’s powder-puff to watch the purple dust fly, and slapped a foot on something imaginary Maggie would have left behind, felt it squish up between my toes warm and mushy—yes, Mama, I’m still at it—gave thanks for the big yellow swallowtails on the butterfly weed, and skip-hopped between the thistle. Whistled a happy tune.

The old fishing hole was a little smaller than I remembered, but just as black and deep that you couldn’t see the bottom of it. Joyfully, the old gum tree was still there, hanging out over the water with a gentle crook in it, so you could repose suitably while you dangled your feet over each side, cocked back and watched your pole. I didn’t fit quite as well as once I did, but it still worked tolerably.

I unlimbered my pole, unwound the line and undid the little sproat hook from the corkstopper—not a cork from a medicine bottle, but the wooden one Daddy bought me one Saturday at Watson’s Store when I was seven—all green, red and yellow, with a stobber through it, so you could peg the line up or down. Dug around in the worm can until I found one and my hand came out worm slimy and caked with black dirt all under my fingernails, threaded ’im on the hook with my tongue consciously sticking past pursed lips, left a little of mister worm on the end to wiggle an invitation. Was purtey-near seven all over again.

Swung the pole and lobbed my hopes out ker-plunk into the shadow of the old gum trunk. While the bees worked the dandy-lyns in happy undertones, and the dragonflies hovered around with those big ol’ goggle eyes. Until one of the smaller ones lit on the stobber of my corkstopper, and I could hear Grandma again, in an Andy Griffith swagger, “good luck, Boy…g-o-o-d l-uu-c-k!”

It was along about then, I think, with the buzzards cutting lazy circles in the mares’ tails of a June-blue sky overhead, the lilting notes of the warblers in the tree-tops, and the long-ago melody of a meadowlark singin’ his heart out on an old fencepost nearby, that I found it again.

Home.

They say you can’t go back again. Well, that ain’t entirely true.

And there’s something ’bout lazing back, not wantin’ to be anywhere else, and watching a corkstopper that’s kinda like having somebody good sketching your likeness out with a pencil on a pad. You get that way-down, mesmerizing, mellow-yellow feeling that holds you pleasantly captive right to the soul…and won’t let go. That just then feels so right you don’t never want it to.

Until, all of a sudden it bobs sharply ’bout twice, ripplin’ the pool, then lays to the water and starts trailin’ off, ’fore it’s jerked clean under, and you rare back on the pole and the line goes tight, the tip all bent and twitchin’, ’fore you haul out a robin redbreast about six ounces, wet and shiny and prettier than an Easter egg. ’Cept it might be a yellow-belly, or a flier, a chubsucker or maybe even a butter-cat.

I stayed until the sun plumb died over the Hopewell Church bridge that afternoon, and walked back up the gentle pasture hillside at dusk, stopped by Methuselah and considered the generations of old shoes under the vine for a time, paused by the remnants of the old home place for a moment or so, before I reluctantly climbed back into the truck to leave for another year…and, yes…there was some sadness in it. But not so much you could tell.

Mostly, I’d found myself again, and I knew I’d be off to Timbuktu sometime again before long. But I’d know from whence I left, and never forget who I was when I was gone.

Had a man once who said, “The older the boy, the younger the man.”

Strikes me he was right. No matter how old you are, you got to hang on to him—the boy—never let him go.

That maybe the day you do, regardless of the latter-dates on a tombstone, is the day the man in you dies too.