It was a modest bullet, for an elk load. Developed about 90 years ago, it was clocking about 2,000 fps when it struck the big quartering-to 6-point at 140 yards. The animal slumped, kicked once and was still. I levered another 180-grain Core-Lokt up the spout and steadied the reticle where the elk had fallen.

No bullet has given me better results on elk than that unassuming blunt softnose, though I’ve used many types in more than 35 chamberings. But every shot, every elk is different, and I’ve seen elk survive multiple strikes from bigger, faster, more expensive bullets. Sample size matters.

A pointed 300-grain bullet might make this .375 cartridge too long. A round nose works to 200 yards!

The Core-Lokt and, more generally, jacketed soft point bullets at modest speeds, comprise a pretty big sample. I’ve used them on game as tough as Cape buffalo to good effect. In reports from other hunters, they often trump racy long-range bullets—in part, at least, because long-range shots often bring poor hits.

Most hunting bullets are of lead, alloyed with antimony to make the lead harder. Jackets became a must in the 1890s, as smokeless powder hiked pressures and bullet velocities. The friction and torque imposed by rifled bores begged tough but malleable jacket metal. Like copper. Tin plating reduced copper fouling until tin “cold-soldered” to a few case mouths pushed pressures to rifle-rending levels. As a component of cupro-nickel, tin was benign. By 1922 Western Cartridge had its Lubaloy jacket of 90 percent copper, 8 percent zinc, 2 percent tin. This “gilding metal” evolved into the 95/5 copper/zinc jackets popular today.

Pointed bullets pre-date WW I when Germany swapped a 226-grain 7.9mm round-nose bullet at 2,090 fps for a 154-grain 8mm pointed “spitzer” at 2,880 fps. The U.S. Army took note, trading its 220-grain 30-caliber round-nose bullet at 2,300 fps for a 150-grain pointed missile at 2,700. These bullets had fully jacketed noses. Hunting bullets are jacketed from the heel to leave the nose open or the core exposed there to prompt upset, or expansion, in game, for destructive internal wounds that bring humane kills.

Big nose cavities and fragile jackets on hollowpoint bullets cause violent upset but increase drag. Smaller nose cavities on hollowpoint match bullets trim drag but behave less predictably in game.

Giving way to poly-tip bullets, traditional pointed softpoints still sell well. Not so much round-nose.

The idea of inserting a hard tip in an expanding bullet occurred to WW I-era wildcatter Charles Newton and got commercial traction as early as 1922 in the Copper Point Expanding bullet by Canadian Industries, Ltd. (CIL). In 1934 Peters introduced a Protected Point Expanding (PPE) bullet. A copper cap fitted over a copper tip extended under the jacket. Making a PPE bullet required more than 50 operations! Winchester followed with its similar Silvertip in 1939. Remington’s Bronze Point, also from the 1930s, had a conical bronze or brass tip.

In 1968 Robert Hutton reported that CIL’s Dominion ammunition was being loaded in Plattsburg, New York, and with its Sabretip bullet, “popular in big game loads [was sold under] the Imperial brand.” Hunters reported using Sabretips in the 1970s, as Norma was developing its round nose Plastic Point bullet.

Nosler brought poly-tip bullets mainstream with its Ballistic Tip (1984). Its tipped AccuBond followed.

Nosler’s Ballistic Tip, announced in 1984, brought the polymer tip mainstream. It was hawked as having “the accuracy of a hollowpoint match bullet, the ballistic coefficient of a sharp-pointed spitzer and the game-taking qualities of Nosler’s own Solid Base [bullet].” Its “polycarbonate” noses were colored to show bullet diameter at a glance: purple for 6mm, blue for .25, brown for 6.5mm, yellow for .270, red for 7mm, green for .30. Ballistic Tips soon became popular in ammunition from Nosler and other brands.

New polymers, better bullets:

While color jazzes up bullets, uniformity makes them accurate. Polymer tips can be made more uniform than noses of hollowpoint bullets. Pointed polymer sets up less drag than lead and won’t deform as easily. In 1998 Hornady fielded the polymer-tip SST bullet. Remington gave it a different color on its AccuTip. Swift’s tipped, bonded Scirocco appeared the following year.

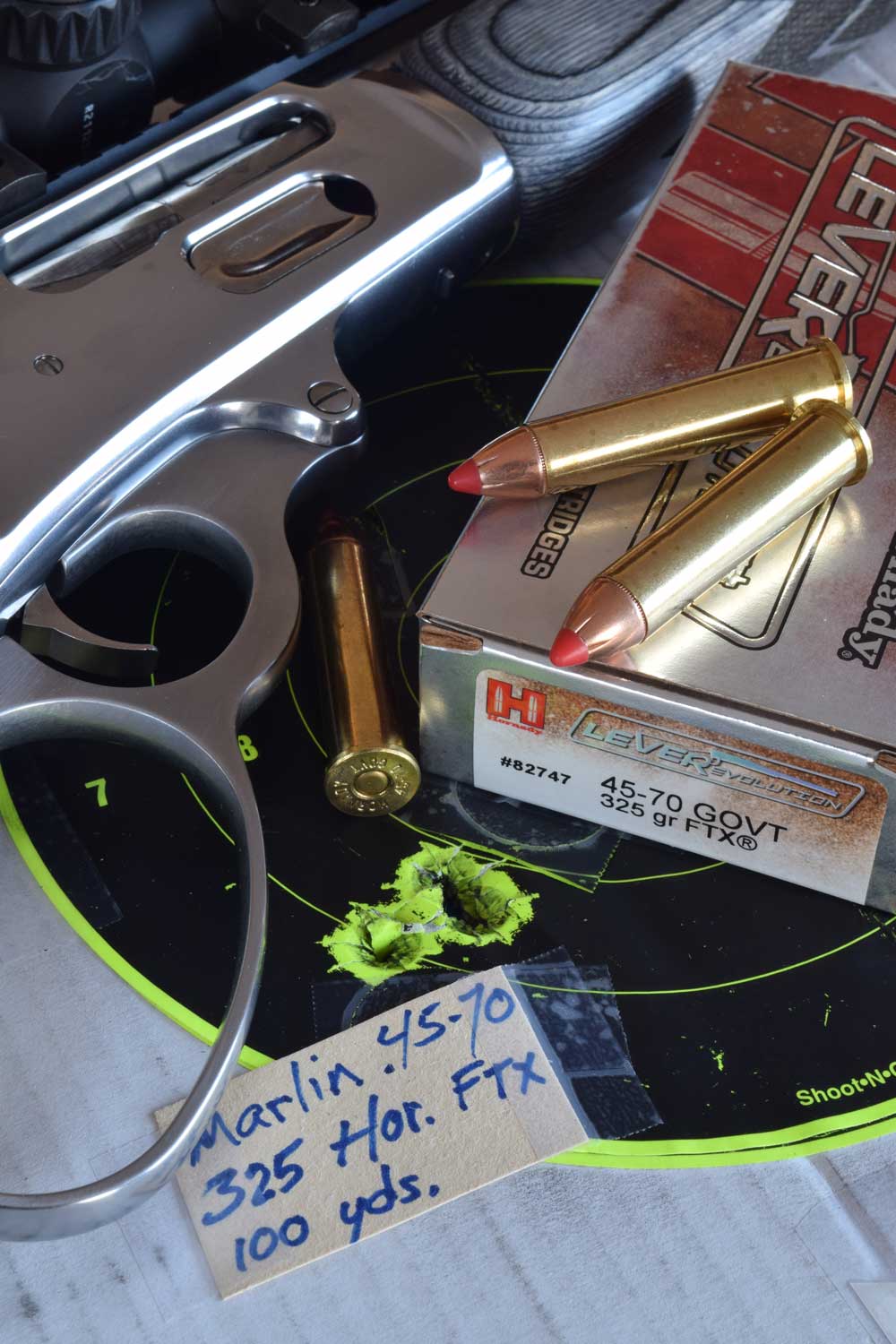

LeverEvolution loads with FTX bullets, first for traditional deer cartridges, serve new numbers too.

Hornady looked beyond cosmetics to design a tipped bullet for use in lever-action rifles with tube magazines. Its FTX bullet appeared in LeverEvolution ammunition in 2005. Instead of Delrin, common in polymer tips, Hornady developed a softer, more resilient material, so neither spring pressure nor the jar of recoil would set off primers resting on bullet tips. The tips would “squish” slightly, then resume pointed form. With peppy charges of new powders, LeverEvolution loads for traditional deer cartridges sent FTX bullets faster, flatter and more accurately than flat- and round-nose soft points. Legions of hunters brought Grandpa’s rifle from the closet. Resurging interest in lever-action rifles is partly due to LeverEvolution loads! They’ve given me minute-of-angle groups, plus clean kills on pronghorn, deer and elk to 160 yards.

Success with the FTX put Hornady ballisticians on another task: explaining changes in ballistic coefficient (BC) during bullet flight. These shifts appeared on instruments tracking bullets with Doppler radar. Like laser rangefinders, Doppler finds an object’s position with the bounce of a beam or a wave. Reading hundreds of data points per shot in a blink, the instrument yields data on velocity, distance and time. In 2011 Hornady’s project leader, Dave Emary, told me the company’s new Doppler unit read bullet location “at intervals of less than 2 feet.”

Many companies have loaded Hornady bullets. This Black Hills ammo sends 140-grain poly-tip SSTs.

When the graph for drag showed bumps in the paths of SST and other poly-tip bullets, Emary and his colleague, Joe Thielen, suspected tip melt was the culprit. “Time in flight, plus the friction imposed by sustained speeds near Mach 3 bring tip temperatures past 800 degrees,” said Thielen. “Air turbulence over the irregular surface of a melted tip boosts drag and destabilizes the bullet. Steeper arcs and diminished accuracy result.”

To keep noses smooth, Hornady developed a Heat Shield Tip with a different material. “Its glass transition temperature (at which polymer turns rubbery) is 475 degrees F, eight times higher than that of other tips,” Emary said. “Its melt temperature of 700 degrees is twice as high. While the noses of very fast bullets reach 700 degrees over 1,000 yards, no bullet gets that hot quickly or stays that hot for long. Poly-tip distortion occurs only when high-BC bullets endure magnum speeds for at least half a second.”

But how would a new ELD-X (Extra Low Drag, Expanding) bullet with a Heat Shield Tip behave in game? Striking gelatin at “150-yard speeds,” it tore wide temporal cavities up to 11 inches long in 23-inch channels. Cavities were predictably smaller at “800-yard speeds” but still impressive. Penetration? Up to 24 inches. Hits on more than 70 game animals showed the ELD-X lethal across a range of impact speeds. Said engineer Jayden Quinlan: “Tip and cavity were refined together to yield the desired rate and extent of expansion. The ELD-X upsets reliably at speeds down to 1,600 fps and resists fragmenting to 2,900.”

That’s a broader range than expected from most softnose and poly-tip bullets, many of which do not expand dependably below 1,800 fps. Hornady notes that solid copper bullets typically require impact speed of 2,000 fps to expand reliably. At low speeds far away, ELD-X bullets reportedly deliver “80 to 90 percent weight retention [with] 20 to 24 inches of penetration.” High-velocity impact can shred the thin nose jacket that prompts expansion, reducing weight retention to “50 to 60 percent,” with wound channels still 24 inches deep. A high InterLock ring retards upset at the shank.

Ballistic coefficient, simply:

A sharp conical nose and long ogive, with a tapered heel and high sectional density (SD, the ratio of a bullet’s weight in pounds to the square of its diameter in inches) yield a high BC number, a measure of the bullet’s ability to cleave air or overcome drag. The ELD-X is a high-BC bullet. So too the Nosler AccuBond LR, Federal’s Terminal Ascent and similar bullets from Berger and other brands.

But what does that number mean?

Hornady engineer Jayden Quinlan clarifies: “BC is relative. It compares the drag of a given bullet with that of a standard bullet.” The shape of a G1 standard bullet resembles that of a WW I artillery shell. The G7 standard, with tapered heel and long 10-caliber ogive (radius of the bullet’s nose between tip and shank) better matches the profile of modern hunting bullets.

Every bullet has a G1 BC and a G7 BC, just as bullet diameter can be expressed in inches and in millimeters. The G1 number is higher because the bullet compares more favorably against the G1 standard than against the sleeker G7.

BC and bullet features that affect it are velocity dependent. At high speeds, a long ogive matters more than a tapered heel in limiting drag. Below 1,600 fps or so, the tapered heel has greater effect.

The most important benefit of a high BC: At long range it flattens a bullet’s arc and helps it retain both speed and energy. Even a small advantage in BC has a visible, if not always substantive, effect.

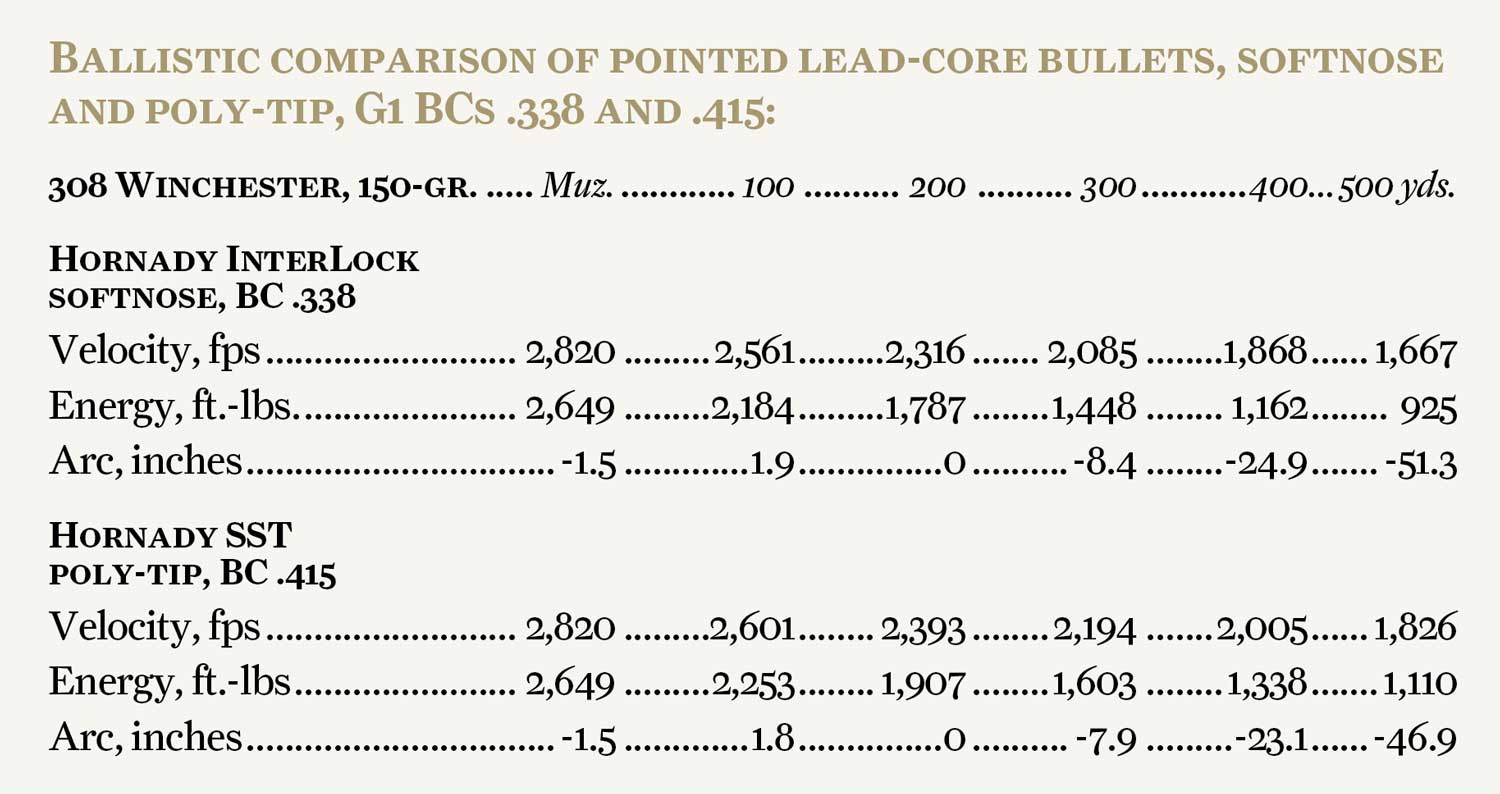

At right is an example of how a softnose bullet compares with a poly-tip of similar form but slightly higher BC when both are launched at the same velocity.

To 300 yards, these bullets strike within half a vertical inch of each other, though at that range the poly-tip bullet has a 109-fps edge in velocity. Differences in speed and energy become more significant farther out; but most big game is killed well inside 300 steps.

A high-BC bullet started slower than a bullet with a blunt nose or one that is short for its diameter (has low sectional density) will eventually pass that bullet as drag applies brakes to both.

Is BC oversold?

Response to Hornady’s ELD-X,with G1 BCs as lofty as .757, inspired competitive polymer-tip bullets with high BCs, long-range accuracy and reliable killing action. Caveats: Seated to yield standard overall length, long bullets intrude deep in the case, reducing powder capacity and affecting pressures. Seated out, they can make the cartridge too long for the magazine or the barrel’s throat. Also, the length of high-BC bullets can call for rifling twist that’s sharper than normal for the cartridge—perhaps 1:9 inches or even 8 1/2, for example, instead of a standard 1:10 when using the longest 7mm bullets. A rate of spin that doesn’t adequately stabilize the bullet will impair accuracy.

Inadequate spin showed up in loads for a rifle I once had. It was bored to 338 Norma, a hunk of a cartridge. My 250-grain handloads shot well, but 285-grain TSXs “key-holed,” turning sideways or end-over-end in flight and losing all sense of direction. Of solid copper, the TSX is longer than jacketed lead-core soft points of the same weight. In fact, 300-grain Sierras didn’t keyhole. Length was the problem, not bullet weight or design. Key-holing can also happen with long lead-core bullets given marginal spin.

Hornady’s FTX bullets have soft, resilient poly tips for tube magazines. They fly flat, print tight groups.

Long, sharp-nosed bullets with colorful polymer tips are fetching. The advantages of high BC are clear: less drop and deflection and harder hits at distance—and often better accuracy. But most big game fairly hunted is killed inside 200 yards, where such bullets have no discernible edge over traditional lead-core soft points—even those with round noses.

Just back from hunting plains game in southern Africa, I shot only four animals. All were within 160 yards. In three safaris before that, open sights kept my shots inside 140 yards. Shooting at dangerous game is almost always much closer. If memory serves, it has been several years since I’ve fired at North American game beyond the 250-yard point-blank range of a 30-06 zeroed at 200 yards. While sweet on FTX bullets in LeverEvolution loads for Marlin and Winchester carbines, I’ve considered high-BC bullets in bolt rifles “long reach in reserve.”

Of course, when next you see a Boone and Crockett buck or bull, it may be pausing for a last look at cover’s edge far, far away. That’s why engineers keep working on bullet tips.