The 1907 winner of the Nobel Prize in literature, Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) achieved fame as a poet and novelist. He is best remembered for poems such as “Gunga Din” and “Fuzzy Wuzzy,” books such as Kim, Captain Courageous and The Jungle Book, and for coining the phrase, “the white man’s burden.” Kipling’s love for fishing and his keen sense of humor become obvious in this bizarre encounter.

It must be clearly understood that I am not at all proud of this performance. In Florida, men sometimes hook and land, on rod and tackle a little finer than a steam-crane and chain, a mackerel-like fish called “tarpon,” which sometime run to 120 pounds. Those men stuff their captures and exhibit them in glass cases and become puffed up. On the Columbia River sturgeon of 150 pounds are taken with the line. When the sturgeon is hooked the line is fixed to the nearest pine tree or steamboat-wharf, and after some hours or days the sturgeon surrenders himself, if the pine or the line do not give way. The owner of the line then states on oath that he has caught a sturgeon, and he, too, becomes proud.

These things are mentioned to show how light a creel will fill the soul of a man with vanity. I am not proud. It is nothing to me that I have hooked and played 700 pounds weight of quarry. All my desire is to place the little affair on record before the mists of memory breed the miasma of exaggeration.

The minnow cost 18 pence. It was a beautiful quill minnow, and the tackle-maker said that it could be thrown as a fly. He guaranteed further in respect to the triangles – it glittered with triangles – that, if necessary, the minnow would hold a horse. A man who speaks too much truth is just as offensive as a man who speaks too little. None-the-less, owing to the defective condition of the present law of libel, the tackle-maker’s name must be withheld.

The minnow and I and a rod went down to a brook to attend to a small jack who lived between the clumps of flags in the most cramped swim that he could select. As a proof that my intentions were strictly honorable, I may mention that I was using a little split-cane rod – very dangerous if the line runs through weeds, but very satisfactory in clean water, inasmuch as it keeps a steady strain on the fish and prevents him from taking liberties. I had an old score against the jack. He owed me two live-bait already, and I had reason to suspect him of coming up-stream and interfering with a little bleak-pool under a horse-bridge, which lay entirely beyond his sphere of legitimate influence. Observe, therefore, that my tackle pointed clearly to jack, and jack alone; though I knew that there were monstrous perch in the brook.

The minnow was thrown as a fly several times and, owing to my peculiar and hitherto unpublished methods of fly throwing, nearly six pennyworth of the triangles came off, either in my coat-collar, or my thumb, or the back of my hand. Fly fishing is a very gory amusement.

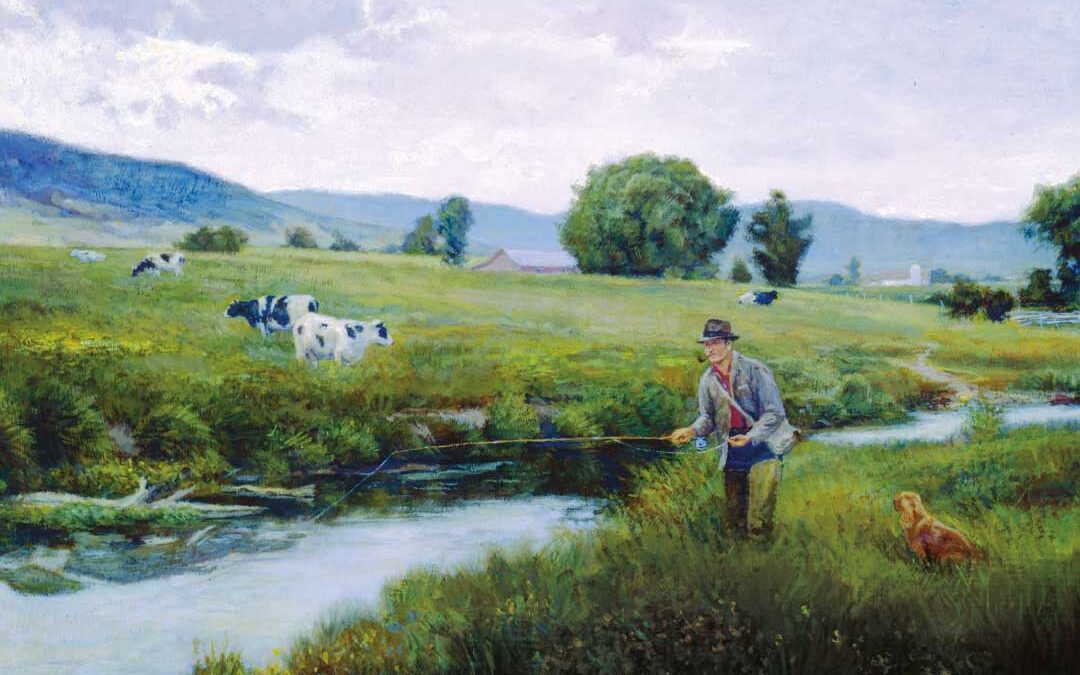

The jack was not interested in the minnow, but towards the twilight a boy opened a gate of the field and let in some 20 or 30 cows and half-a-dozen cart-horses, and they were all very much interested. The horses galloped up and down the field and shook the banks, but the cows walked solidly and breathed heavily, as people breathe who appreciate the Fine Arts.

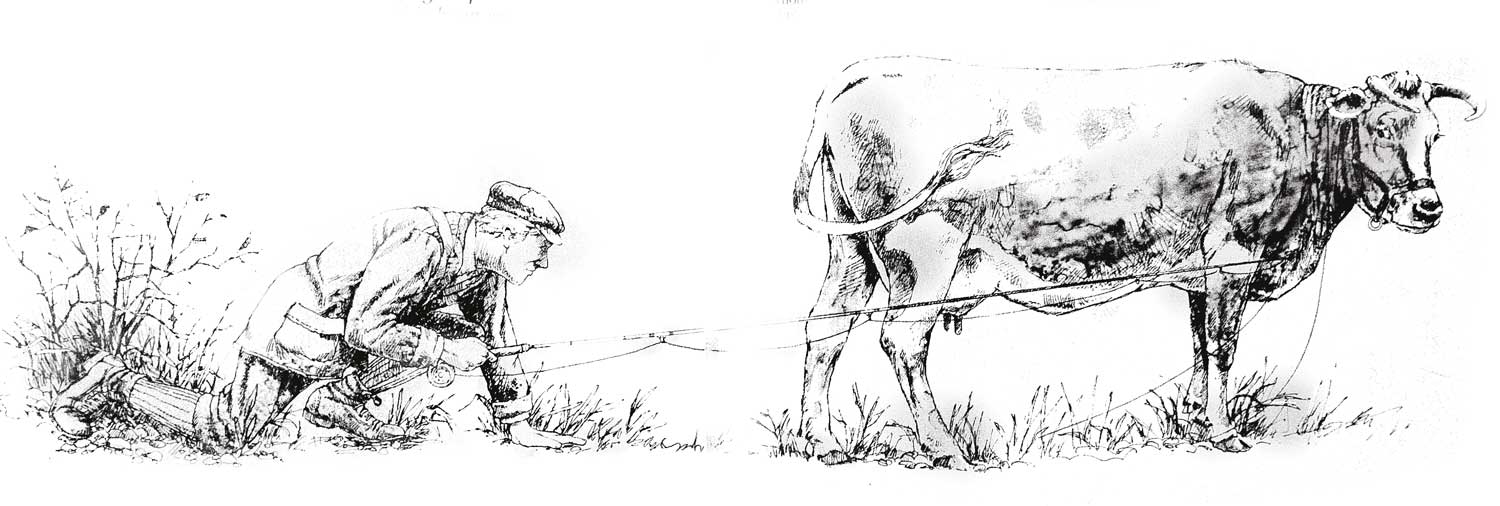

By this time I had given up all hope of catching my jack fairly, but I wanted the live-bait and bleak-account settled before I went away, even if I tore up the bottom of the brook. Just before I had quite made up my mind to borrow a tin of chloride of lime from the farmhouse – another triangle had fixed itself in my fingers – I made a cast, which for pure skill, exact judgment of distance and perfect coincidence of hand and eye and brain, would have taken every prize at a bait-casting tournament. That was the first half of the cast. The second was postponed because the quill minnow would not return to its proper place, which was under the lobe of my left ear. It had done thus before, and I was supposed it was in collision with a grass tuft, till I turned round and saw a large red and white bald-faced cow trying to rub what would be withers in a horse with her nose.

She looked at me reproachfully, and her look said as plainly as words: “The season is too far advanced for gadflies. What is this strange disease?”

I replied, “Madam, I must apologize for an unwarrantable liberty on the part of my minnow, but if you will have the goodness to keep still until I can reel in, we will adjust this little difficulty.”

I reeled in very swiftly and cautiously, but she would not wait. She put her tail in the air and ran away. It was a purely involuntary motion on my part: I struck. Other anglers may contradict me, but I firmly believe that if a man had foul-hooked his best friend through the nose, and that friend ran, the man would strike by instinct. I struck, therefore, and the reel began to sing just as merrily as though I had caught my jack. But had it been a jack, the minnow would have come away, I told the tackle-maker this much afterwards and he laughed and made allusions to the guarantee about holding a horse.

Because it was a fat innocent she-cow that had done me no harm the minnow held – held like an anchor-fluke in coral moorings – and I was forced to dance up and down an interminable field very largely used by cattle. It was like salmon fishing in a nightmare. I took gigantic strides, and every stride found me up to my knees in marsh. But the cow seemed to skate along the squashy green by the brook, to skim over the miry backwaters and to float like a mist through the patches of rush that squirted black filth over my face.

Sometimes we whirled through a mob of her friends – there were no friends to help me – and they look scandalized; and sometimes a young and frivolous cart-horse would join in the chase for a few miles, and kick solid pieces of mud into my eyes; and through all the mud, the milky smell of kine, the rush and the smother, I was aware of my own voice crying: “Pussy, pussy, pussy! Pretty pussy! Come along then, puss-cat!”

You see it is so hard to speak to a cow properly, and she would not listen – no, she would not listen.

Then she dropped, and the moon got up behind the pollards to tell the cows to lie down; but they were all on their feet, and they came trooping to see. And she said, “I haven’t had my supper, and I want to go to bed, and please don’t worry me.”

And I said, “The matter has passed beyond any apology. There are three courses open to you, my dear lady. If you’ll have the common sense to walk up to my creel, I’ll get my knife and you shall have all the minnow. Or, again, if you’ll let me move across to your near side, instead of keeping me so coldly on your off side, the thing will come away in one tweak. I can’t pull it out over your withers. Better still, go to a post and rub it out, dear. It won’t hurt much, but if you think I’m going to lose my rod to please you, you are mistaken.”

And she said, “I don’t understand what you are saying. I am very, very unhappy.”

And I said, “It’s all your fault for trying to fish. Do go to the nearest gate-post, you nice fat thing, and rub it out.”

For a moment I fancied she was taking my advice. She ran away and I followed. But all the other cows came with us in a bunch, and I thought of Phaeton trying to drive the Chariot of the Sun, and Texan cowboys killed by stampeding cattle, and “Green Grow the Rushes, O!” and Solomon and Job, and “loosing the bands of Orion,” and hooking Behemoth, and Wordsworth who talks about whirling round with stones and rocks and trees, and “Here we go round the Mulberry Bush,” and “Pippin Hill,” and “Hey Diddle Diddle,” and most especially the top joint of my rod.

For a moment I fancied she was taking my advice. She ran away and I followed. But all the other cows came with us in a bunch, and I thought of Phaeton trying to drive the Chariot of the Sun, and Texan cowboys killed by stampeding cattle, and “Green Grow the Rushes, O!” and Solomon and Job, and “loosing the bands of Orion,” and hooking Behemoth, and Wordsworth who talks about whirling round with stones and rocks and trees, and “Here we go round the Mulberry Bush,” and “Pippin Hill,” and “Hey Diddle Diddle,” and most especially the top joint of my rod.

Again she stopped – but nowhere in the neighborhood of my knife – and her sisters stood moonfaced round her. It seemed that she might, now, run towards me, and I looked for a tree, because cows are very different from salmon who only jump against the line, and never molest the fisherman. What followed was worse than any direct attack. She began to buck-jump, to stand on her head and her tail alternately, to leap into the sky, all four feet together, and to dance on her hind legs. It was so violent and improper, so desperately unladylike, that I was inclined to blush, as one would blush at the sight of a prominent statesman sliding down a fire escape, or a duchess chasing her cook with a skillet. That flopsome abandon might go on all night in the lonely meadow among the mists, and if it went on all night – this was pure inspiration – I might be able to worry through the fishing line with my teeth.

Those who desire an entirely new sensation should chew with all their teeth, and against time, through a best waterproofed silk line, one end of which belongs to a mad cow dancing fairy rings in the moonlight; at the same time keeps one eye on the cow and the other on the top joint of a split-cane rod. She buck-jumped and I bit on the slack just in front of the reel; and I am in a position to state that that line was cored with steel wire throughout the particular section which I attacked. This has been formally denied by the tackle-maker, who is not to be believed.

The wheep of the broken line running through the rings told me that henceforth the cow and I might be strangers. I had already bidden goodbye to some tooth or teeth; but no price is too great for freedom of the soul.

“Madam,” I said, “the minnow and twenty feet of very superior line are your alimony without reservation. For the wrong I have unwittingly done to you I express my sincere regret. At the same time, may I hope that Nature, the kindest of nurses, will in due season – “

She or one of her companies must have stepped on her spare end of the line in the dark, for she bellowed wildly and ran away, followed by all the cows. I hoped the minnow was disengaged at last, and before I went away looked at my watch; fearing to find it nearly midnight. My last cast for the jack was made at 6:23 p.m. There lacked still three and a half minutes of the half-hour; and I would have sworn that the moon was paling before the dawn.

“Simminly someone were chasing they cows down to bottom o’ Ten Acre,” said the farmer that evening. “Twasn’t you, sir?”

“Now under what earthly circumstances do you suppose I should chase your cows? I wasn’t fishing for them, was I?”

Then all the farmer’s family gave themselves up to jam-smeared laughter for the rest of the evening, because that was a rare and precious jest, and it was repeated for months, and the fame of it spread from that farm to another, and yet another at least three miles away, and it will be used again for the benefits of visitors when the freshets come down to spring.

But to the greater establishment of my honor and glory, I submit in print this bald statement of fact, that I may not, through forgetfulness, be tempted later to tell how I hooked a bull on a Marlow Buzz, how he ran up a tree and took to water, and how I played him along the London-road for 30 miles, and gaffed him at Smithfield. Errors of this kind may creep in with the lapse of years, and it is my ambition ever to be a worthy member of that fraternity who pride themselves on never deviating by one hair’s breadth from the absolute and literal truth.