But the man he adored most in the world had offered only a brief touch of his hand to the old dog’s nose, a helpless attempt at a consoling word, and even though he had lingered a moment, the man had turned away to loose the pair of clamoring, younger dogs that kenneled alongside him. He knew now, as his kennelmates danced happily about and the man started away, that he was not to go again. He looked with longing eyes toward the familiar blue truck that waited at the kennel path. The tailgate was down, and the two racing dogs cleanly cleared it, hurling themselves up and neatly into the open box.

Once he could do that. Once it had been him who was never left behind.

Him. Who was the first-string dog in the run. To whom the man would come first. To hurry the gate open, turn him out, tease him with incitant greetings, and playful cuffs. Until his desire flamed like wind-driven wildfire and his heart nearly thumped out of him.

Him. Big and strong, as hard and chiseled as sculpted granite. Who was loosed to make the glad, mad dash, launching himself so fiercely he slammed against the back of the box – rocking the truck – kenneling up to go. To go do the thing he was born for, burned for, would die for.

Once it had been him, who shivered and slavered at the sight of the man, and the gun, and the blazing certainty of freedom. Freedom from the 6-by-12 run that had imprisoned four-fifths of his life. Freedom to hunt, to query the wind, to run and run until he was brought up tight against the slender, unmistakable waft of mercurial magic that sang “birds.” That took hold of him so abruptly and forcibly and perfectly that it was beyond his means to understand or control, slamming him into the promise and artistry of a rigid stand. So wonderfully mesmerized that he dared not move. Dared not blink. While he waited faithfully for the man, the sharp bark of the gun and the after-essence of feathers between his jaws.

And even though the taste of feathers was rich and good, most of all he had lived to be sent on, on-and-on, to find the magic again.

But that was long ago. So long ago, now, though still he begged, most of the hope was gone.

Slowly the old dog detached himself, lowering his tail and taking small, slow steps to his house, gathering himself momentarily and pushing himself stiffly up into its threshold. He settled there, fidgeting to rearrange his gaunt frame, so that he could lie more comfortably.

English Setter by Gustav Muss-Arnolt

He had lost much of the muscle mass that had once cushioned his bones. No matter how much he might run – were he free to – or how well he was fed, or how much he ate, he could never gain it back again. It could only be given once, and it had been wrestled away.

Time was a merciless master, and age was its servant.

He could never again be what he used to be.

He did not contemplate this or pity himself for it. That was God’s blessing to his kind. Though in body he suffered its limitations, his will would never concede.

For always, there had been the unquenchable fire within him, a white-hot ingot of longing so overwhelming it would never be quelled.

Always it had been undeniable, and always it had conquered all.

The old dog drooped, letting his head and muzzle settle across his paws. The shadows had risen in his eyes again. There was a milky cloudiness about them, and deeper within them an uncertain sadness. Day-by-day, he was failing, and perhaps he grasped it more than any man could know. His only separation from the daily, accelerating process of dying was to watch the sparrows that flitted about the run, gleaning bits of food. He had pointed them more than once when he was a puppy. And butterflies. Before he discovered the loftier and more evocative spoor of game.

That was long ago too, even though – in the laughing sunlight of summer – he still surrendered himself to point a monarch or a swallow-tail, should one light enticingly by. Would stand for ten minutes, entranced, rocking on his feet with the burning fatigue in his old legs – until almost he collapsed. Offering a sheepish glance at flush, should the man be watching.

Now it was winter and the butterflies were gone. He bunched and shivered. For his was to deal with the moment, and he had passed the disappointment of the one behind him, to cope with the one at fore.

The day was cloudy, damp and freezing, and absent the elation of the hunt or the normal insulation of body fat, there was nothing but to endure it. Aided by a mean north breeze, it numbed him through and through. It was that way now – especially the long, frigid nights – until often it hurt, despite the orchard grass that provided his bedding. It had not been so keen when he was sturdy, in his prime and absorbed with anticipation.

The old dog’s eyelids sagged. Still he shuddered and could not stop. He rose awkwardly and settled again, tucking more tightly. Burying his muzzle in the warm crevice between his flank and inner thigh, wrapping his tail closely around his tuck – like a scarf.

Dozing fitfully, he twitched and trembled for another eventless hour. Another barren hour, among ever too many others, in a life that was almost spent, and at best so briefly unfair. An hour more still and it seemed he was sleeping.

Along with the wane of his eyes, the old dog’s hearing was greatly diminished, and though he could not sense it, this was much the reason he was no longer allowed to go. For the last time he had gone, he was unable to maintain contact with the man – as he had all the years – by his ears and eyes alone. Was lost from him in his forever reach for birds, could not hear him calling, and had to thrice find him with his nose. Each time there had accrued a growing and frightening absence. Until the man worried that he would be lost and never return. Bringing an unfathomable sadness.

Yet, through his fitful slumber, the old dog heard somehow the tiny telltale brush of the back door, as it opened against the sill. So that suddenly his head lifted, and he listened keenly for a moment, then piled quickly out of his house – along with the rest of the kennel – to greet the advancing woman.

His old eyes had brightened anew and his tail was beating, for always she brought good things to eat and happiness with her. She approached upwind, and he could smell her before he could see her. She smelled differently from the man. Softer and sweeter.

All his life they had been special friends. He was beside himself, wriggling and grinning, quivering with joy . . . when she came first to his run and held out a hand with a fat slab of turkey between her fingers. Taking it gingerly, he thanked her, then gulped it down.

The sounds she made were always gentle and caring. She asked him “Back,” opened the gate and stepped inside. With level eyes, he waited for her touch. Lifting a cupped hand, she cradled his graying muzzle, knelt and spoke to him in tones of empathy and understanding. He could not perceive the words or know her tears, but he knew the kindness of her body language and the soothing tenor of her tone . . . oh, so very, very well.

He melted against her and begged for more, his tail beating a steady tattoo against her leg. Begged her to stay. To please never leave.

After a time she did, and he watched her away, until he could see her no more. Then followed her with his nose until she had closed the back door again, and the sweetness of her scent was gone.

The old dog reared at the gate, thrusting his nose high in the air, trying to recover it. But it was gone. Then, as he teetered on two straining legs, the balance of his body tilted, and the full measure of his weight shifted onto the gate.

He had not expected it to give.

But the latches rattled momentarily and sprang open, because with the very gentleness of everything the woman did – in the detachment of her concern for him – she had failed to completely seat them. She had let the gate come to rest, but had not nudged it firmly into place. One in a thousand times, but it had happened, and she had departed . . . unaware.

Suddenly the old dog was falling.

In his younger years he would have caught himself and landed on his feet. Now his aging equilibrium failed, and he slammed brutally against the ground, splayed half in-and-out of the run. The momentum of the returning gate struck him meanly in the ribs, and he yelped against the cutting pain. Wallowing and struggling, he managed to gather his frail old legs under him and climb to his feet.

He shook himself violently, almost falling again, throwing aside the disorientation of the fall. For a few moments he stood uneasily, taking stock of himself. As his wits recovered, so did his composure and slowly his tail started beating. For he had found himself again, and in the same gladdening instant realized he was free!

For a moment he was held between two worlds. But comfort, without hope, could not salve his soul.

May Doo by Gustav Muss-Arnolt (1858-1927) Courtesy: Copley Fine Art Auctions

Deep inside him, the old fire flamed. His banked old spirit flared. Like a shower of sparks, fanned by a sudden swirl of the wind. He could feel his blood rising, the power of it surging through his veins.

He started clumsily, in a shuffle. Then lifted himself to a trot. Unsurely, at first, then more certainly. In a few seconds more he had recovered the lifelong rhythm of his gait. His carriage had from birth been exceptionally fluid, and as he had matured, it had evolved into a kinetic expression of supreme athleticism and consummate desire that was poetic. It did not flow with the seamless beauty or bounce that once it had, but it was yet compelling; had the man been watching, it would have been abetted the lovelier by the poignancy of his years.

He covered the half-frozen ground with growing speed, his tail swinging happily over his back with each beat of his stride.

The old dog could feel his strength swelling back, fueled by the intensity of freedom, and the fury of his desire. . . could feel his will ascending. . . the iron-driven, never-die determination to find birds. Reaching inside himself, he pledged his all to the hunt, and his gait evened almost to a glide.

He crossed the creek in two bounds and a splash, heaving himself up the off bank, and then swiftly through a wedge of woods. Across a broad, open pasture, and then through a larger block of timber . . . before finding the path that led to the sprawling beanfields he remembered as perfectly as if it were yesterday, though he had not set foot on them in more than three years.

There he had run as a yearling, flown like he had wings, and there he had found and pointed and held his first covey of wild quail, until the man had come up, and he could stand it no longer. His instincts to spring had burst like a boiler against a bottle-cap, and he had taken the birds out, barking gleefully at their departure. And the man had laughed with him.

Two years later, when he was three, he had stood along those edges again, this time leaning into the scent, tall and proud . . . the progeny of destiny. Had swelled the higher, when the man had put the birds up, and scarce the liberty of an inch, he had stood on his toes to mark them away. Until the man walked back to him and sent him happily to serve the gun, to deliver to hand the two that were left behind.

From there had followed an extruded season of understanding and trust between the dog and the man, as no other on earth. Together, they had traveled broadly, and he had stood many times, in many places, on many birds. Always, they had gone together. From Georgia to the Dakotas, to the hills of Oregon and Idaho, and on, to the vast plains of Montana and Alberta. To the painted autumn forests of New England and the farmland peninsula of Quebec, where there he had held birds as well.

And always, he had proven big as the country.

The old dog had not understood why it had ended, why, together, they did not go any more. When so desperately there remained his need.

Without a stutter, the old dog crossed the great, muddy Mississippi beanfield – though already he had traveled more than two miles – to gain the advantage of the incoming breeze from its off-side edge. When he had the wind he turned, grabbing the weedy edge, undeterred by the huge, unknown distance to its end.

It did not matter. It never had. It was only there to conquer, as he had all the years. There was no surrender.

The old dog settled into his gait, reading the breeze, searching for the tiny trace of mystery that for his entire being had remained evergreen. Pushing faster and faster, as fast as he could go, to catch the next few yards, the next 300, the next half-mile . . .

His breathing was coarse, for he was less than he had been, and he was soft and unconditioned.

That did not matter either.

What mattered was the moment. What mattered was now. What mattered was the same thing that had mattered since he had taken the first breath of his life.

On he pushed, searching and searching. Driving . . . the harder still, though he could not know the birds were no longer there in the numbers once they had been. Another half-mile fell away. Then another.

The old dog had reached the end of the first long field, was hunting the hedgerow between it and the next . . . when like the snap of a checkcord he was spun sideways and struck motionless. As if the moment itself had been arrested, and he was bound within it.

Slowly he lifted fully back to his feet, leaning heavily against the incoming wind. His head and tail were not the parenthetical equinox once they had been, but his stand was taut and attractive. Most of all, it was true. The birds were caught superbly, captive in the anxious suspension between flight and fear.

Minutes dragged by. The old dog held until he tottered, waiting for the man. Finally, his legs gave, and he surrendered himself to sit. Something he had never done, in all his years.

When, at last he knew the man would not come . . . and the scent had faded . . . he stood again. The nervous covey had hoofed a getaway. It took him a minute or so to master the relocation. Now he had them again. Once more the electric, hypnotic spell of them rendered him to a trance.

This time the birds were tittery and restless, would not stay, and blew up and away in a splutter and boil. The old dog swelled high as he could, on shaky legs, watching them off. Shivering with the bluster of their flush.

The incense of the find was, to his liberated spirit, as gas on an inferno. Away he raced, on and away. Driving himself the more furiously. Catching the downwind edge of the next great field and promising himself to the horizon.

He found again in the next hour, yet again after that. Blazing, still . . . ever still . . . with the quest for more.

Relentlessly, he fought on. Though rapidly he was pressuring his limits.

On, until his gait was breaking and periodically he stumbled. On, until his heart pounded and his breath came in raking, raspy gasps. On, until he plodded slower and slower.

But on. Ever on. Until he staggered. Until in his eyes a sudden darkness grew . . . though around him day was not done, and the sun still set the bays to glimmer.

Abruptly, his heart burst. His feet failed and he slid headlong into the dirt. He lay on his side, heaving, his withered old legs paddling helplessly for purchase . . . as the blood from the ruptured vessel flooded his chest, leaking his life away.

In a few more moments, his time had passed. Fifteen years from the turn of the earth that had brought him into this old world, he was gone.

For weeks, amid sleepless nights and troubled days, the man had searched for him. Until he was so totally exhausted he couldn’t any more. Thinking the worst, praying for the best, regretting more deeply than ever he had imagined that he had not had gone with the old dog in his waning days. While the woman sobbed, her eyes red and swollen, with the guilt that she had been the instrument of his departure.

A month passed. Then another. More and more, they found themselves in disrepair. Much as the old dog himself.

The hope was gone.

He had been the mightiest of their years. Tough as nails. As savvy on birds as a fox on cottontails. As determined and independent as a flash flood to find them. As wondrously thrilling when he did, as the drama in a stormy sky.

The man had loved him for his courage; the woman, for his care. Never could they have wanted the way he would leave.

Together, they constructed a small cairn by their doorstep. Atop it, the man placed a weathered copper plaque.

Upon it he engraved the old dog’s name.

So that everyday, as they passed, they would see it. And be reminded that he had lived.

Three years afterward and eleven miles removed – on a greening April morning – a farmer climbed off his tractor to adjust his harrow so it would cut more deeply into the warming soil.

Picking up a handful of the freshly disturbed loam, he turned it in his doubled palms, measuring the make of it. He was pleased. The earth was breathing again.

He looked about. The immense field sprawled away, dwarfing him.

Ahead, a limb lay at its edge, impeding his work. He stepped to remove it. As he did, he noticed a shard of bone.

He prodded it with the toe of his boot and it did not move. So he stubbed at it harder, and when it was unearthed, stooped and picked it up.

It was the moldering, gray-green skull of a dog. Likened to any other. Maybe a shepherd, a setter or a hound.

Casually, he dropped it back to the dirt.

For a small moment the man wondered . . . how it got there.

It did not matter. It had never mattered. What mattered was the same thing that had mattered since the old dog had taken the first breath of his life.

What mattered, had mattered even more than love.

In time, the circumstances of his life had grown hopeless. But the old dog’s death was his own.

Note: This article originally appeared in the 2012 May/June issue of Sporting Classics magazine.

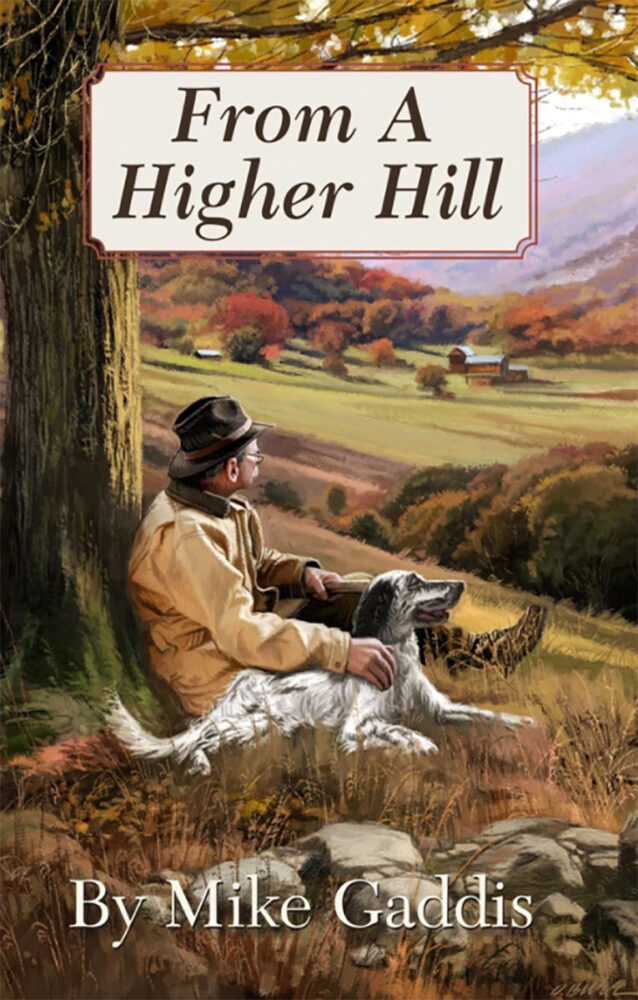

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come.

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come.

Upon this lofty precipice, one of the most celebrated and insightful sporting authors of our time again reaches beyond himself, this time retrieving sixty-five more episodic explorations of the sporting life, the whole of which transcend contemporary perspective, and ascend to rare and unexcelled poignancy. Buy Now