No fish had ever exerted a greater influence on the thoughts, the imagination, the manners or the moral character of his pursuers.

Uncle Eb was a born lover of fun. But he had a solemn way of fishing that was no credit to a cheerful man. It was the same when he played the bass viol, but that was also a kind of fishing at which he tried his luck in a roaring torrent of sound. Both forms of dissipation gave him a serious look and manner, that came near severity. They brought on his face only the light of hope and anticipation or the shadow of disappointment.

We had finished our stent early the day of which I am writing. When we had dug our worms and were on our way to the brook with pole and line, a squint of elation on Uncle Eb’s face. Long wrinkles deepened as he looked into the sky for a sign of the weather, and then relaxed a bit as he turned his eyes upon the smooth sward. It was no time for idle talk. We tiptoed over the leafy carpet of the woods.

Soon as I spoke he lifted his hand with a warming “Sh-h! ”

The murmur of the stream was in our ears. Kneeling on a mossy knoll we baited the hooks; then Uncle Eb beckoned to me.

I came to him on tiptoe.

“See thet there foam ‘long side o’ the big log?” he whispered, pointing with his finger.

I nodded.

“Cre-e-ep up jest as ca-a-areful as ye can,” he went on whispering. “Drop in a leetle above an’ let’er float down.”

Then he went on, below me, lifting his feet in slow and stealthy strides.

He halted by a bit of driftwood and cautiously threw in, his arm extended, his finger alert. The squint on his face took a firmer grip. Suddenly his pole gave a leap, the water splashed, his line sang in the air and the fish went up like a rocket. As we were looking into the tree-tops, it thumped the shore beside him, quivered a moment and flopped down the bank. He scrambled after it and went to his knees in the brook coming up empty handed. The water was slopping out of his boot legs.

“Whew!” said he, panting with excitement as I came over to him. “Reg’lar ol’ he one,” he added, looking down at his boots. “Got away from me – consarn him! Hed a leetle too much power in the arm.”

He emptied his boots, baited up and went back to his fishing. As I looked up at him, he stood leaning over the stream jiggling his hook. In a moment I saw a tug at the line. The end of his pole went underwater like a flash. It bent double as Uncle Eb gave it a lift. The fish began to dive and rush. The line cut the water in a broad semi-circle and then went far and near with long, quick slashes.

The pole nodded and writhed like a thing of life. Then Uncle Eb had a look on him that is one of the treasures of my memory. In a moment the fish went away with such a violent rush, to save him, he had to throw his pole into the water.

The pole nodded and writhed like a thing of life. Then Uncle Eb had a look on him that is one of the treasures of my memory. In a moment the fish went away with such a violent rush, to save him, he had to throw his pole into the water.

“Heavens an’ airth!” he shouted, “the ol’ settler!” The pole turned quickly and went lengthwise into the rapids. He ran down the bank and I after him. The pole was speeding through the swift water. We scrambled over logs and through bushes, but the pole went faster than we. Presently it stopped and swung around.

Uncle Eb went splashing into the brook. Almost within reach of the pole he dashed his foot upon a stone and fell headlong in the current. I was close upon his heels and gave him a hand. He rose hatless, dripping from head to foot and pressed on. He lifted his pole. The line clung to a snag and then gave way; the tackle was missing. He looked at it silently, tilting his head. We walked slowly to the shore. Neither spoke for a moment.

“Must have been a big fish,” I remarked.

“Powerful! ” said he, chewing vigorously on his quid of tobacco as he shook his head and I looked down at his wet clothing. “In a desp’rit fix ain’t I?”

“Too bad!” I exclaimed. “Seldom ever hed sech a disapp’ intment,” he said.

“Rather counted on ketchin’ thet fish – he was s’ well hooked! ” He looked longingly at the water a moment. “If I don’t go hum,” said he, “an’ keep my mouth shet, I’ll say sumthin’ I’ll be sorry fer.”

He was never quite the same after that. He told often of his struggle with this unseen, mysterious fish, and I imagined he was a bit more given to reflection. He had had hold of the “ol’ settler of Deep Hole,” – a fish of great influence and renown there in Faraway. Most of the local fishermen had felt him tug at the line one time or another. No man had ever seen him for the water was black in Deep Hole. No fish had ever exerted a greater influence on the thought, the imagination, the manners or the moral character of his contemporaries.

Tip Taylor always took off his hat and sighed when he spoke of the “ol’ settler.” Ransom ‘Walker said he had once seen his top fin and thought it longer than a razor.

Ransom took to idleness and chewing tobacco immediately after his encounter with the big fish, and both vices stuck to him as long as he lived.

Everyone had his theory of the “ol’ settler.” Most agreed he was a very heavy trout. Tip Taylor used to say that in his opinion “‘Twas nuthin’ more’n a plain, overgrown, common sucker,” but Tip came from the Sucker Brook country where suckers lived in colder water and were more entitled to respect.

Mose Tupper had never had his hook in the “ol’ settler” and would believe none of the many stories of adventure at Deep Hole that had thrilled the township.

“Thet fish hes made s’ many liars ’round here ye dunno who t’ b’lieve,” he had said at the corners one day, after Uncle Eb had told his story of the big fish. “Somebody ‘t knows how t’ fish hed oughter go ‘n ketch him fer the good o’ the town – thet’s what I think.”

Now Mr. Tupper was an excellent man but his incredulity was always too bluntly put. It had even led to some ill feeling.

He came in at our place one evening with a big hook and line from ” down east” – the kind of tackle used in salt water.

“What ye goin’ t’ dew with it?” Uncle Eb inquired.

“Ketch thet fish ye talk s’ much about – goin’ t’ put him out o’ the way.”

“Taint fair,” said Uncle Eb, “it’s reedic’lous. Like leading a pup with a log chain.”

“Don’t care,” said Mose, ”I’m goin’ t’ go fishin’ t’morrer. If there reely is any sech fish – which I don’t believe there is – I’m gain’ t’ rassle with him an’ mebbe tek him out o’ the river. Thet fish is sp’ilin’ the moral character o’ this town. He oughter be rode on a rail – thet fish hed.”

How he would punish a trout in that manner Mr. Tupper failed to explain, but his metaphor was always a worse fit than his trousers and that was bad enough.

It was just before haying, and there being little to do, we had also planned to try our luck in the morning. Whe, at sun rise, we were walking down the cow path to the woods, I saw Uncle Eb had a coil of bed cord on his shoulder.

“What’s that for?” I asked.

“Wall,” said he, “gain’ t’ hev fun anyway. If we can’t ketch one thing, we’ll try another.”

We had great luck that morning and when our basket was near full we came to Deep Hole and made ready for a swim in the water above it. Uncle Eb had looped an end of the bed cord and tied a few pebbles on it with bits of string.

“Now,” said he presently, “I want t’ sink this loop t’ the bottom an’ pass the end o’ the cord under the drift wood so t’ we can fetch it ‘crost under water.”

There was a big stump, just opposite, with roots running down the bank into the stream. I shoved the line under the drift with a pole and then hauled it across where Uncle Eb drew it up the bank under the stumproots.

“In ’bout half an hour I cal’late Mose Tupper ‘ll be ‘long,” he whispered. “Wisht ye’d put on yer clo’s an’ lay here back o’ the stump an’ hold on t’ the cord. When ye feel a bite give a yank er two an’ haul in like Sam Hill – fifteen feet er more guicker’n scat. Snatch his pole right away from him. Then lay still.”

Uncle Eb left me, shortly, going upstream. It was near an hour before I heard them coming. Uncle Eb was talking in a low tone as they came down the other bank.

“Drop right in there,” he was saying, “an’ let her drag down, through the deep water, deliberate like. Git clus t’ the bottom.”

Peering through a screen of bushes I could see an eager look on the unlovely face of Moses. He stood leaning toward the water and jiggling his hook along the bottom. Suddenly I saw Mose jerk and felt the cord move. I gave it a double twitch and began to pull. He held hard for a jiffy and then stumbled and let go, yelling like mad. The pole hit the water with a splash and went out of sight like a diving frog. I thought it well under the foam and driftwood. Deep Hole resumed its calm, unruffled aspect. Mose went running toward Uncle Eb.

”’S a whale!” he shouted. “Ripped the pole away quicker’n lightnin’.”

“Where is it?” Uncle Eb asked.

“Tuk it away f’m me,” said Moses. “Crabbed it jes’ like thet,” he added with a violent jerk of his hand.

“What d’ he dew with it?” Uncle Eb inquired.

Mose looked thoughtfully at the water and scratched his head, his features all a-tremble.

“Dunno,” said he. “Swallered it mebbe.”

“Mean t’ say ye lost hook, line, sinker ‘n pole?”

“Hook, line, sinker ‘n pole,” he answered mournfully. “Come nigh haulin’ me in tew.”

“‘Taint possible,” said Uncle Eb.

Mose expectorated, his hands upon his hips, looking down at the water.

“Wouldn’t eggzac’ly say ’twas possible,” he drawled, “but ’twas a fact.”

“Yer mistaken,” said Uncle Eb.

“No I haint,” was the answer, “I tell ye I see it.”

“Then if ye see it, the nex’ thing ye orter see ‘s a doctor. There’s sumthin’ wrong with you sumwheres.”

“Only one thing the matter o’ me,” said Mose with a little twinge of remorse. ”I’m jest a natural born perfec’ dum fool. Never c’u’d b’lieve there was any sech fish.”

“Nobody ever said there was any sech fish,” said Uncle Eb. “He’s done more t’ you ‘n he ever done t’ me. Never served me no sech trick as thet. If I was you, I’d never ask nobody t’ b’lieve it. ‘S a little tew much.”

Mose went slowly and picked up his hat. Then he returned to the bank and looked regretfully at the water.

“Never see the beat o’ thet,” he went on. “Never see sech power ‘n a fish. Knocks the spots off any fish I ever hearn of.”

“Ye riled him with that big tackle o’yourn,” said Uncle Eb. “He wouldn’t stan’ it.”

“Feel jest as if I’d hed holt uv a wil’ cat,” said Mose.

“Tuk the hull thing – pole an’ all- quicker ‘n lightnin’. Nice a bit 0 ‘ hickory as a man ever see. Gol’ durned if I ever heern o’ the like o’ that, ever.”

He sat down a moment on the bank.

“Got t’ rest a minute,” he remarked. “Feel kind o’ wopsy after thet squabble.”

They soon went away. And when Mose told the story of “the swallered pole,” he got the same sort of reputation he had given to others. Only it was real and large and lasting.

“What d’ ye think uv it?” he asked, when he had finished.

“Wall,” said Ransom Walker, “wouldn’t want t’ say right out plain t’ yer face.”

“‘Twouldn’t be p’ lite,” said Uncle Eb soberly.

“Sound a leetle ha’sh,” Tip Taylor added.

“Thet fish has jerked the fear o’ god out o’ ye – thet’s the way it looks t’ me,” said Carlyle Barber.

“Yer up ‘n the air, Mose,” said another. “Need a sinker on ye.”

They bullied him – they talked him down, demurring mildly, but firmly.

“Tell ye what I’ll do,” said Mose sheepishly. I’ll b’lieve you fellers if you’ll b’lieve me.”

“What, swop even? Not much!” said one, with emphasis.

“‘Twouldn’t be fair, Ye’ve ast us t’ b’lieve a genuwine out ‘n out impossibility.”

Mose lifted his hat and scratched his head thoughtfully. There was a look of embarrassment in his face.

“Might a ben dream in’,” said he slowly. “I swear it’s gittin’ so here ‘n this town a feller can’t hardly b’lieve himself.”

“Fur’s my experience goes,” said Ransom Walker, “be’d be a fool ‘ f he did.”

“‘Minds me o’ the time I went fishin’ with Ab Thomas,” said Uncle Eb. “He ketehed an ol’ socker the fust thing. I went off by myself ‘n got a good-sized fish, but ‘twant s’ big’s hisn. So I tuk ‘n opened his mouth ‘n poured in a lot o’ fine shot. When I come back, Ab he looked at my fish ‘n begun t’ brag. When we weighed ’em, mine was leetle heavier.”

“‘What!’ says he. “‘Taint possible thet leetle cus uv a trout’s heavier ‘n mine.”

“‘Tis sartin,” I said.

“‘Dummed deceivin’ business,” said he as he hefted ’em both. ‘Gittin’ so ye can’t hardly b’lieve the stillyurds.”

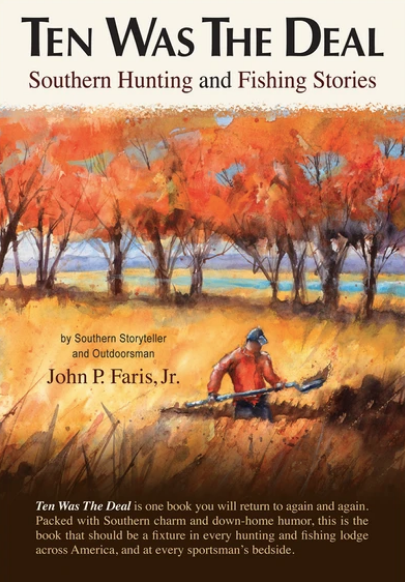

Ten Was The Deal is more than a book of stories about hunting and fishing, it offers all of the enchantment of yarns spun while sitting on the tailgate of a pickup truck; all of the lore of tales told around a campfire. Ten Was The Deal is definitely a keeper.

Ten Was The Deal is more than a book of stories about hunting and fishing, it offers all of the enchantment of yarns spun while sitting on the tailgate of a pickup truck; all of the lore of tales told around a campfire. Ten Was The Deal is definitely a keeper.

John’s stories are set in pinewoods, along Piedmont streams, in Lowcountry fields, or along the coast of the Carolinas. This volume reveals a boy’s journey to manhood: turkey hunting with a grandfather, duck hunting with a dad, and sharing his first kiss with a fishing buddy. Buy Now