We sat and watched the buffalo in silence, as my 25-year fantasy slowly metamorphosed, solidifying into a memory I will carry until the day I die.

Sand and thorn bush and Cape buffalo go together like gin and tonic and lime. Leaving camp in the predawn chill with nothing in your stomach but some tea and the knowledge of going out to confront a mythical beast on his own turf. Jolting over the track in early-morning emptiness, your professional hunter looking smaller and younger, or else smaller, older and malarial, than he did the night before in the light of the campfire.

Sand and thorn bush and Cape buffalo go together like gin and tonic and lime. Leaving camp in the predawn chill with nothing in your stomach but some tea and the knowledge of going out to confront a mythical beast on his own turf. Jolting over the track in early-morning emptiness, your professional hunter looking smaller and younger, or else smaller, older and malarial, than he did the night before in the light of the campfire.

But you have to go. You can’t wait for sunshine and courage. The problem is, you see, that during the night, the buffalo come out into the open to waterholes to wallow and drink in the safety of darkness. At dawn, they head back to sanctuary. Your best (and sometimes your only) chance is to intercept them before they get back to the thorn thickets. Or, at least, to pick up their trail early and come up with them while they are still easy-going in their cool morning tranquility.

And so you venture out — reluctantly, hesitantly, shivering with cold and…

“The buffalo water over there on those flats,” Patrick murmured. “They generally cross the road just up ahead and go into the thorns.”

An urgent tapping told us the trackers had spotted hoofprints in the sandy road, and Patrick smoothly swung the Toyota off to the left and in under a canopy of trees growing out of a huge abandoned anthill.

“Ready?”

“I guess so.”

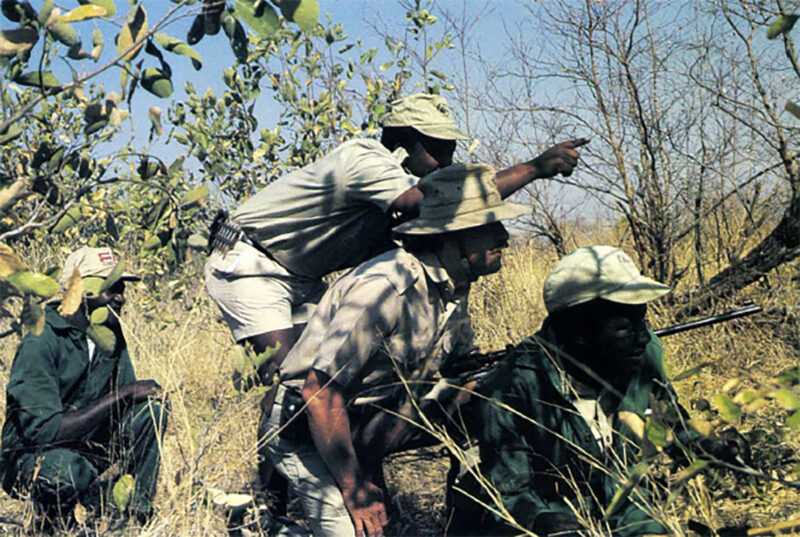

In the early morning grayness, we set out with the trackers coursing ahead like bird dogs, moving in a half-crouch among the rain trees, pausing often to search the brush ahead for the tell-tale horizontal black line of the buffaloes’ backs. As we moved, we hunched lower and lower until eventually we were on our hands and knees, finally crawling on our stomachs through the sand.

Selelo, the senior tracker, raised his hand a fraction of an inch and froze.

“Down,” Patrick whispered.

The buff were up ahead, and I caught glimpses of black through brushy openings. Occasionally a horn appeared. Painfully, we moved forward, an inch at a time. And then they stampeded. Without warning. We saw a dust cloud begin to rise, felt the earth shake and then heard the muffled rumble of hundreds of hooves — and only at the last did we see movement. They were gone, leaving us to climb to our feet and set out, once more, in pursuit.

The buff were up ahead, and I caught glimpses of black through brushy openings. Occasionally a horn appeared. Painfully, we moved forward, an inch at a time. And then they stampeded. Without warning. We saw a dust cloud begin to rise, felt the earth shake and then heard the muffled rumble of hundreds of hooves — and only at the last did we see movement. They were gone, leaving us to climb to our feet and set out, once more, in pursuit.

As the sun rose into the cloudless sky over the Okavango Delta, so did the temperature. Dust from repeated stampedes hung in the air and mixed with the sweat on our faces. The old barnyard smell of buffalo surrounded us as we pursued the herd, moving ever deeper into the thorns. Alerted now, they were increasingly skittish, running away seemingly at nothing, until by 11:00 o’clock it was obvious there was no hope.

We turned back for the car, trudging through the heat of the day with the sun nailed to our backs and the car, with its precious water tank, a good six miles away through the soft, sucking sand. The sparse trees gave no shade, and I was soon trapped in a private cocoon of heat, thirst and nausea. Even the sight of a pair of lions, uncaged and 40 yards away, aroused from their siesta by our approach, caused only a brief flutter of interest. Water. It was all I could think of.

“So that’s buffalo hunting,” I croaked, leaning up against the Toyota while Selelo unlimbered the water jug.

“That’s it,” Patrick said.

Taking our cue from the lions, we drank long and slow, ate cold impala chops and pickles from the lunch hamper, drank some more, and then rested as the sun scorched its way across the sky. Around three, we resurrected ourselves and cruised through the late afternoon, searching for buffalo. By 4:30, shooting time had run out, at least for buffalo. You don’t want start something you won’t have time to finish.

Patrick called back to Sell, and he handed tow chilly cans of Castle Lager down into the cab, and we drove slowly home in the gathering darkness.

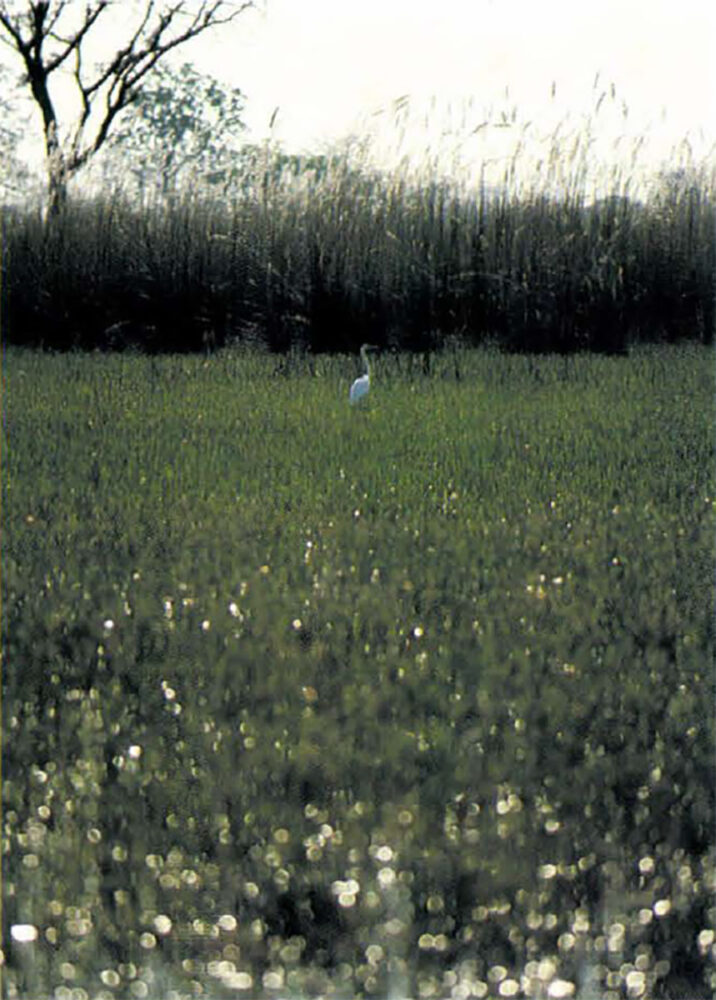

Camp was a permanent cluster of tents grouped along an expanse of marsh, and we could see the friendly, flickering firelight across the water as the road skirted the swamp.

It is called the Kaporota Camp for the sausage trees that grow around it. Towering ebonies, more than a yard thick, shade it throughout the day and we could sit in front of our tents and look out across the marsh where herds of red lechwe and tsessebe waded and browsed. Usually there were sable and impala as well. I had the impression of sitting in a theatre box, while a play was staged for our private benefit.

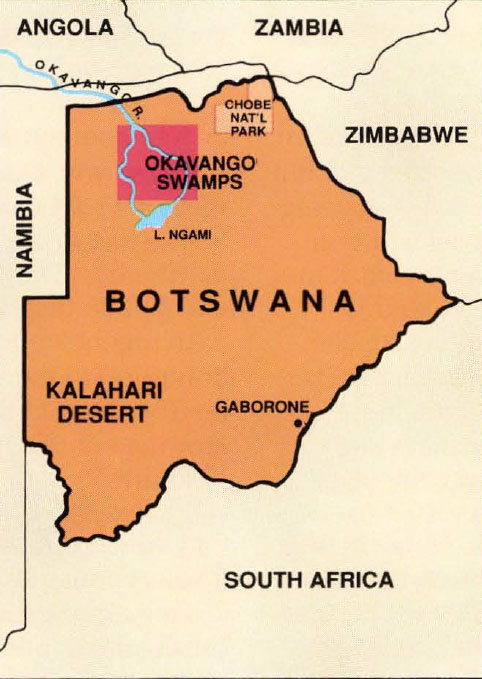

This is Tony Henley’s special camp, the one he and his protégé, Patrick Mmalane, normally hunt from. It is 25 miles of twin ruts in the sand, though swamp and bush. After an hour-long flight from Man to an airstrip on the Okavango, and then half-an-hour by motorboat through the papyrus-lined channels to Mecom, and then an hour of jolting in the back of a safari car Kaporota looked like home and mother. Since it was to be our home for the next week, that was only appropriate.

We arrived in the heat of the day and promptly sat down to lunch in the open, in front of the mess tent.

We arrived in the heat of the day and promptly sat down to lunch in the open, in front of the mess tent.

Tony contemplated the offering of cold ham and corned beef with a jaundiced eye. The fact that it was served by a steward in a mess jacket did not make it any more appealing.

“I should warn you chaps, there’s no meat in camp. Unless one of you shoots something this afternoon, this is what we’ll be eating.”

He looked at us pointedly as he said it, and responsibility settled heavily on our shoulders.

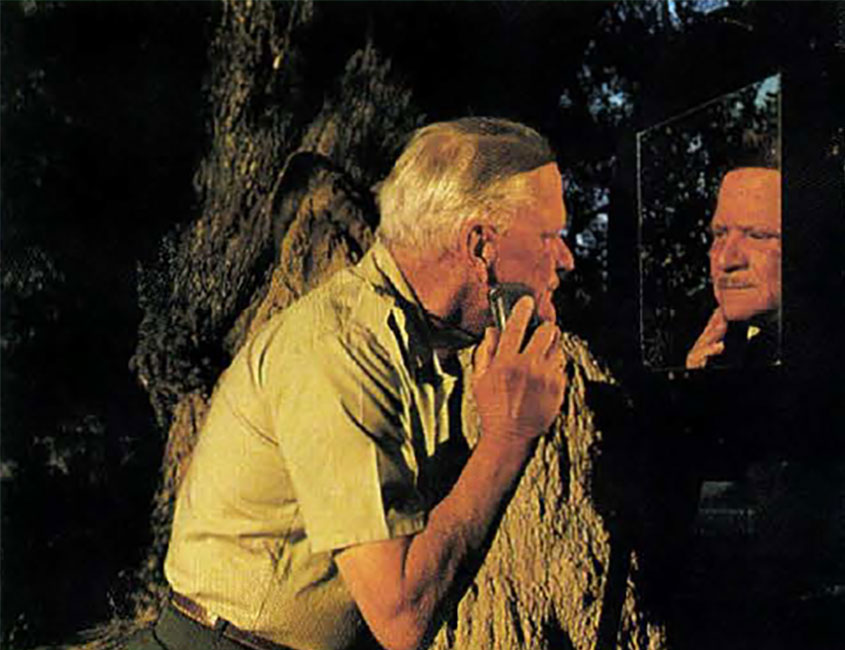

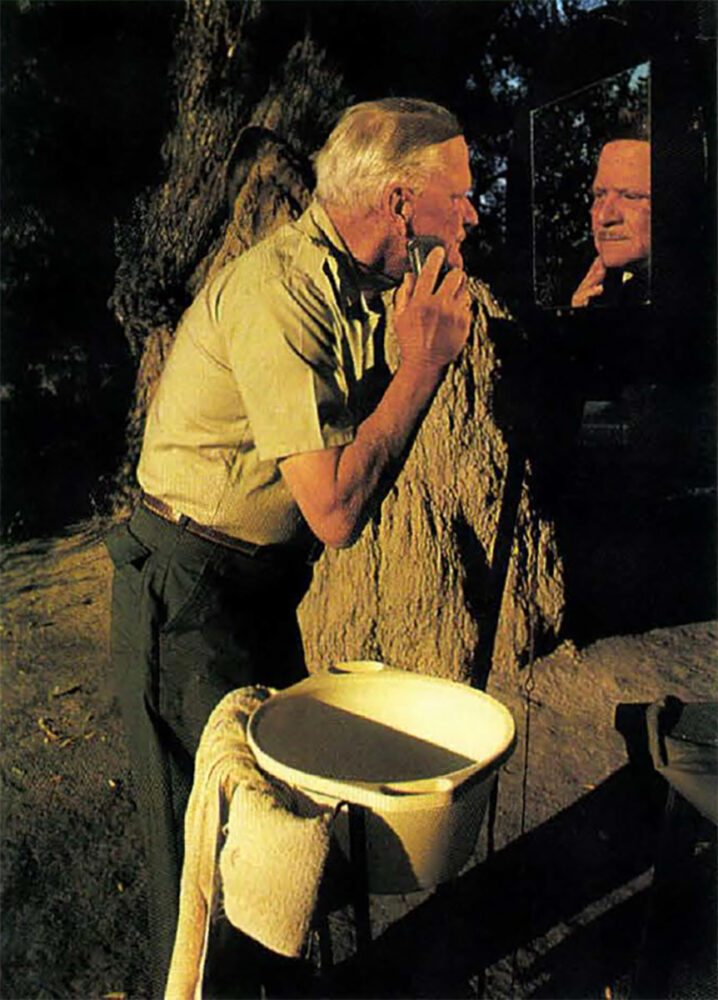

Tony Henley is one of the genuine characters of the safari world. He’s been hunting professionally for 40 years, the last 30 with Safari South in Botswana. Before that, he was variously a hunter and game warden in Kenya and Uganda; a contemporary and long-time friend of the legendary Harry Selby, the two are now colleagues in Safari South. Aside from being a ‘brilliant hunter'(Robin Hurt’s description), Henley is renowned for two things: he is an accomplished ornithologist and keeper of the flame of the professional hunter as a professional, a hunter and a gentleman. Imagining an unshaven Tony Henley is like imagining the King of England in cut-off jeans.

One of Henley’s pet hates is being referred to as a ‘guide.’

“A guide is an unshaven, denim-clad horse wrangler,” he snorts. Were it not for the relentless twinkle in his eye, you might even think him stuffy.

Henley is not just old school; in the case of his young Tswana protege, Patrick Mmalane, he is the school.

Patrick Mmalane is a graduate of Sandhurst, the Royal Military College in England which is itself no slouch when it comes to teaching correctness. After a stint as a professional soldier with the Botswana Defense Force, Captain Mmalane retired to become Safari South’s first black African PH under the unforgiving eye of the impeccable Mr. Henley.

Mmalane has been a fully qualified and licensed PH for several years now, with all the rights and privileges that entails, including his own string of trackers and retainers. Still, he and Henley are good friends and often hunt together. Like now.

With lunch finished, we sorted ourselves out. Jack Carter, Finn Aagaard and Henley, old friends all, elected to hunt together; Patrick and I headed off in a different direction. As we pulled out of camp, I realized that I had finally fulfilled an enduring dream: to be on my own in Africa, with just my PH and our trackers, off in pursuit of a dozen fantasies.

With lunch finished, we sorted ourselves out. Jack Carter, Finn Aagaard and Henley, old friends all, elected to hunt together; Patrick and I headed off in a different direction. As we pulled out of camp, I realized that I had finally fulfilled an enduring dream: to be on my own in Africa, with just my PH and our trackers, off in pursuit of a dozen fantasies.

The Okavango is a land given to fantasy. To call it a swamp is to grossly misrepresent it. After the rains, when the water is high and the grass is lush, it is the largest inland delta in the world. Cool, clear rivers flow through papyrus marshes, feeding huge swamps and sheltering everything from hippos to sitatunga. Palm trees sway on luxurious islands where elephants roam. The rivers lap on sandy shores, which, 100 yards inland, become classic sand-and thornbush Cape buffalo country.

Whatever your fantasy, the Okavango can accommodate you. In my case, it was Cape buffalo a big, black, heavy-horned, mean, vindictive old mbogo with sore feet and the disposition of your ex-wife’s lawyer.

Of course, it was too late that afternoon to start out after buffalo, so with Tony’s plaintive plea for meat ringing in our ears, Patrick and I setoff with our two trackers, Selelo Sedirilwe and Kelorang Lorato. We collected a nice but not spectacular impala (liver for breakfast and chops for lunch), and the next day managed a good warthog and a craggy old tsessebe. We took the afternoon off to sit in front of the mess tent, quaff a few ales, watch the wildlife parade in the swamp in front and plan the Cape buffalo campaign.

But by the second morning of hunting buffalo, frisky enthusiasm had been replaced by unsmiling determination and a new appreciation of exactly what it entailed. Sand and thorn bush, romantic as it sounds, is rough stuff. We were soon down on our stomachs, worming through the sand and raintree leaves that crumbled like corn flakes, with thorns digging into our elbows, listening to the buffalo munching and moving just yards away and straining for a glimpse of them. Drops of sweat from our foreheads evaporated as they hit the scorching sand.

Overhead, we could see giraffes moving through the bush like clippers before a lazy wind, and the pancake prints of elephants traversed the sand with tiny raintree flowers scattered across them like amethyst teardrops.

All very romantic. All very picturesque. All very well, but where was my big buffalo? Just before noon, we gave it up and did our five-mile sweating slog back to the car to have lunch under a leopard-orchid tree and doze into the afternoon, watching the red lechwe cavorting near the road.

“Pretty, aren’t they?”

“I think I have to get me one of those, one of these days.”

“You’ll have to come back.”

“You’ll have to come back.”

“Just what I need – another fantasy.”

Patrick is not optimistic about hunting Cape buffalo late in the day. Even if you connect, it is more luck than strategy. But we had nothing better to do, and Selelo, our senior tracker, was insistent that we try and… well, a wise hunter listens to his trackers. And at least we wouldn’t be walking. We eased the truck down the road and started to meander through the bush in thes tillness of a hot Okavango afternoon.

At precisely 2:35, there came an urgent tap on the cab and a few whispered words in Setswana.

“Out. Load.” Patrick said tightly He was not smiling.

I eased a round into the chamber of the .416 Weatherby, and we slunk into the tangle of brush and trees uprooted by elephants. Beyond an anthill were black patches visible through the branches. Cape buffalo.

Patrick took one look and set up the shooting sticks. There was only one set of horns visible. Low. Facing us. Unmoving. Good horns. Very good horns. I tried to settle the bouncing crosshairs, jerked the trigger and the herd stampeded, melting into the bush, leaving nothing but a cloud of fine dust in the air and the sound of receding hooves.

We ran to where he’d been. Blood. With Selelo leading, we followed after the herd. There was no bull. But there had definitely been blood. We walked, pausing, scrutinizing each bush.

“It’s no use:’ Patrick said. “Let’s get the car and cruise around. We have a couple of hours. We should be able to pick him up. He ran right into the center of the herd.”

And then suddenly, there was the blood trail. Broad bright splashes in the sand, leading off at an angle. Off into the bush, alone. Patrick and the trackers conferred in low tones, not looking at me. Selelo absently peeled the bark from a long, thin branch. For the umpteenth time I checked the cartridge in the chamber, the spares in the pouch, the feel of the safety.

And then suddenly, there was the blood trail. Broad bright splashes in the sand, leading off at an angle. Off into the bush, alone. Patrick and the trackers conferred in low tones, not looking at me. Selelo absently peeled the bark from a long, thin branch. For the umpteenth time I checked the cartridge in the chamber, the spares in the pouch, the feel of the safety.

“Selelo first, then Kelorang, then me, then you,” Patrick said. “You watch the sides.”

They turned away, and it struck me what a glorious afternoon it really was, with the sun dappling the sand through the trees and creating golden halos from the dust that hung in the air and the silence of the absolute stillness drowning out the buzzing of tsetse flies and the broad splotches of blood turning brown and crystalline on the baking sand.

We moved off quickly-slowly, Selelo on the blood trail with his peeled white wand flicking to each splotch and smear and track in turn; Kelorang, the junior tracker, stayed close, peering ahead over Selelo’s head; Patrick followed, scanning ahead and to the sides. Holding my .416 like a grouse gun, I concentrated on keeping up, trying to watch both sides at once. For half-an-hour we followed the trail. Once we found where he had stumbled over a downed log, scattering blood on the sand.

“He’s weakening,” Patrick said. And off we went again. We could see about 20 yards at best through the thorns. Then they closed in, shutting off visibility except for the odd avenue which had been kept open, the odd inexplicable tunnel we could peer down 50 yards or more. It was down one of these tunnels that Selelo spotted our bull, standing motionless, facing away from us. His hand shot up, and we froze. Patrick reached back and propelled me ahead of him, up behind Selelo.

“Shoot quickly,” he breathed. There was no time for shooting sticks, no time to look for a rest, no time to breathe, no time to think. There was just time to settle the crosshairs at the base of his tail and shoot. The shot anchored him squarely, and his back end dropped as if a rug had been pulled out. Bellowing, he tossed from side to side as if his haunches were nailed to the ground.

“Shoot again!”

I shot again. And again. Reload. Jam. Curse. Clear. Reload. Aim. Shoot. Move up. Shoot again. Reload again. Another jam. Curse. Clear. Shoot. The bull, mercifully anchored by the perfect spine shot at the base of the tail, was now soaking up one 400-grain bullet after another in unbelievable Cape buffalo vitality and refusing to die or give in or accept the inevitable.

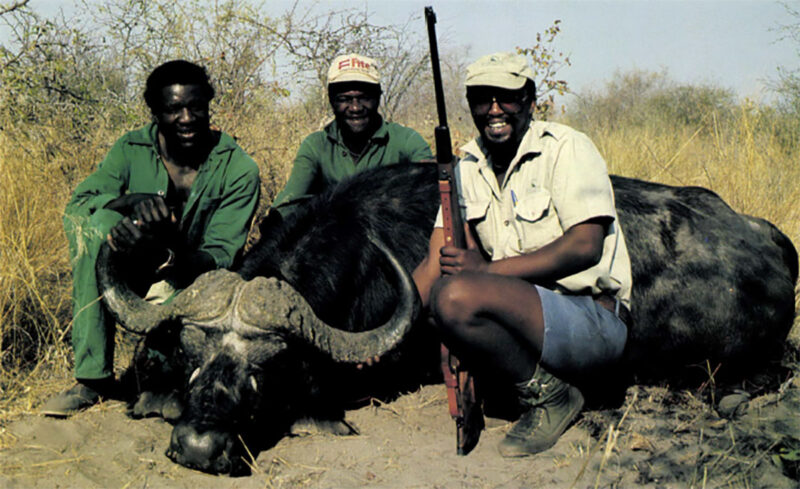

Until, finally, with me out to his side barely 20 yards away, he lunged one last time and I fired a seventh shot into his shoulder and he died staring straight at me, unblinking, a big old Cape buffalo bull in the sand and the thorns and the heat of a late Okavango afternoon.

Patrick came up behind me and put his hand on my shoulder, and we sat and watched the buffalo in silence, as my 25-year fantasy slowly metamorphosed, solidifying into a memory I will carry until the day I die.

More than just a thrilling safari story, this book is a must-have resource for anyone dreaming of their own African adventure. Donarski shares expert information on not only tracking and harvesting South Africa’s most popular trophy species, but also selecting rifles and ammunition, getting in shape, negotiating the reams of necessary paperwork, dressing properly, and many other essential details.

More than just a thrilling safari story, this book is a must-have resource for anyone dreaming of their own African adventure. Donarski shares expert information on not only tracking and harvesting South Africa’s most popular trophy species, but also selecting rifles and ammunition, getting in shape, negotiating the reams of necessary paperwork, dressing properly, and many other essential details.

“Too many people believe that Africa is gone, particularly South Africa,” writes Donarski, “It is not.” And through his words and photos, he shows today’s South Africa, a breathtakingly beautiful land of rugged mountains, wildlife rich plains, and quaint villages filled with friendly natives. Buy Now