Two men wandered into the Ontario Central Airways (OCA) office one afternoon while I was manning the front desk. How strange it was that I could instantly tell that they were used to being in charge. They wore short brown leather jackets and the standard issue khaki shirts and trousers of local pilots and guides but, somehow, did so more fashionably. They had the chiseled facial features of my heroes in the Western movies shown in Saturday afternoon matinees at the local cinema, but more Gregory Peck than John Wayne.

“Can I help you gentlemen?” I asked in my coolest tone, trying to hide the unexplained abashedness I was experiencing in their presence.

“You can if you know of any good fishing available locally for muskies. We have a week off and have driven up from Minneapolis. We’ve caught a lot of medium sized northerns at fishing camps along the highway from Fort Frances, but we want to catch a muskie. A really good sized one.

“We heard about Vermilion Bay but when we got there all the cabins were booked and so we took a chance, a flyer, on driving up Highway 105, the dusty way to the end of the road, sure enough. To nowhere, someone told us.

“We reckoned a place this remote would have some less known muskie fishing close by, as Eagle Lake is jammed with tourists. A Twin-City newspaperman caught a 40-pounder in it a month ago and wrote a column, so the word spread like wildfire throughout Minnesota and the rest, as they say, is history. You can’t rent a boat or cabin or hire a guide for love or money in Vermilion Bay or thereabouts.”

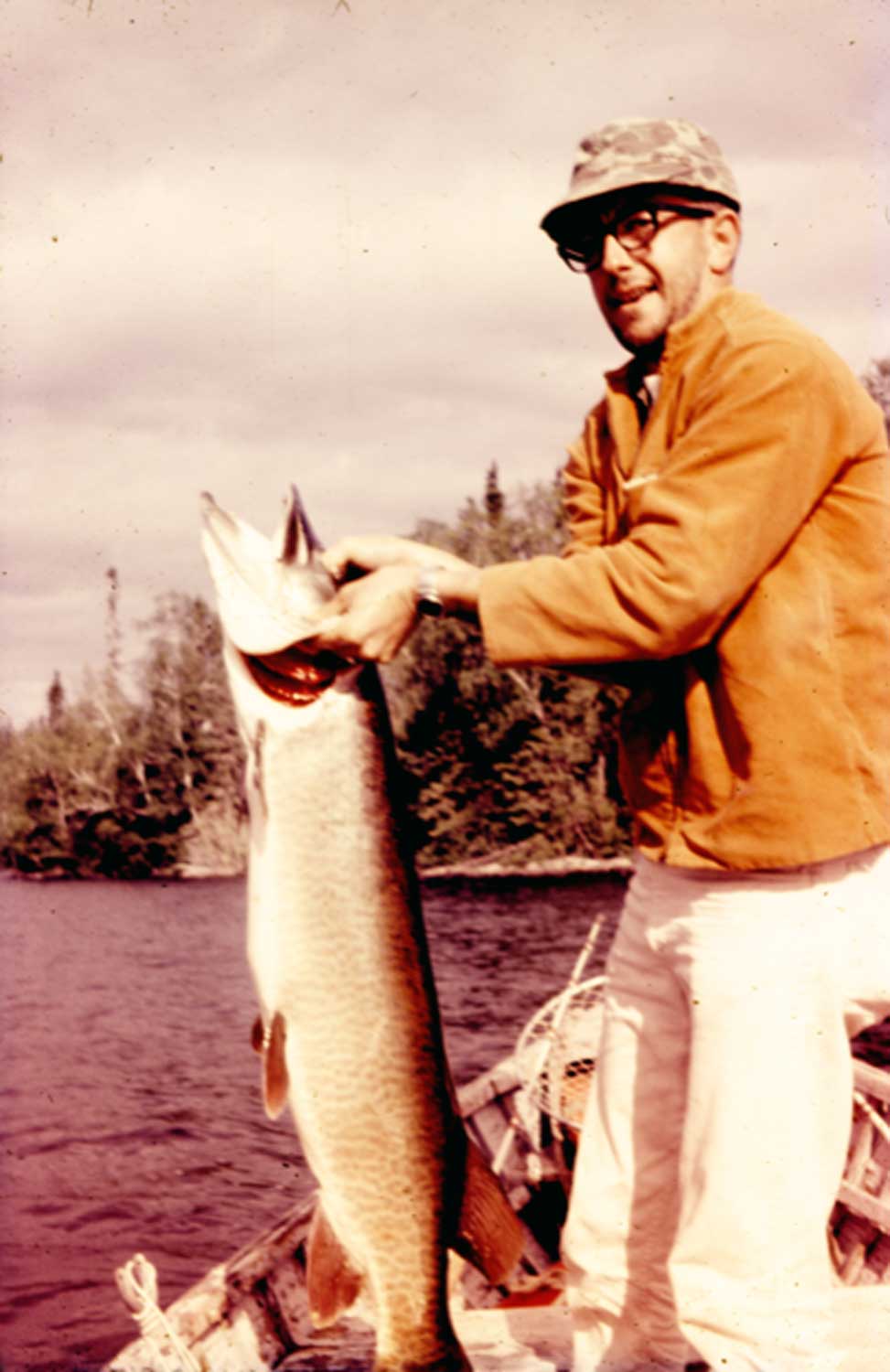

Roger Mueller hoists a 45-pound muskie.

I was very familiar with fishing in Rat Lake and its connecting waters but had only heard heart-pounding rumors about Flat Lake near where my dad worked in the mine. Stories of giant muskellunge the size of alligators had filtered back to OCA from an ebullient, allegedly somewhat bull-slinging local character, Elmer Roth, whom I had overheard describe landing a 30-pounder to the gathered bush pilots in the OCA waiting room. My problem was neither my dad nor I owned a car to get to either lake.

“I know of one lake where a guy recently landed a huge muskie but there is no camp there and only a few locals have boats on the dock. Almost nobody fishes it. Everyone around here is after walleyes.”

“That sounds perfect,” exclaimed the more outgoing of the two, now smiling and squinting like Clint Eastwood in “The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.”

“Are there any local guides we can hire? Boats?”

“I’m afraid not, but I know someone who has a boat there I might be able to make arrangements for, and I have done a bit of guiding locally,” neglecting to add that I had only fished for pike and walleye, never even having seen a muskie.

“Great! Our lucky day!” They high fived one another, something I had seen only in U.S. sporting magazines and in the sports newsreels shown before the main features in the local theater.

We agreed to meet the following morning at the OCA office. Elmer very kindly agreed to let me use the boat and kicker (outboard motor) that were stashed in an old boathouse at the lake. The next problem was I didn’t have muskie gear, only the closed-faced reel I had been gifted by the Californian golden boy, adequate for smaller fish but not for the monsters I had heard about and since read about in the U.S. Fishing Annual I perused while sitting on the floor of the Winnipeg Supply Store.

Oh well, I would have to be strictly a guide for the day.

The next morning, I hurried downtown in a rainstorm with a lunch pail of sandwiches, apple pie and hot coffee Mom had put together. Good thing too, it was chilly. The more voluble American, who had introduced himself as Trevor, was waiting for me looking a little dubious about the rain, but keen to go.

“My buddy is from Florida. Doesn’t fish in cold, wet weather,” he explained. “He’s curling up with a good book, but I’m a Minnesota boy. I’m used to miserable fishing conditions. Let’s hit the road.”

I noticed he had two rods equipped with Swedish Ambassadeur 5000 level-wind reels I had read so much about but could only dream of owning. They cost more than $50—a fortune.

Sure enough, my instincts were right on. Both Trevor and his friend were senior airline pilots for TWA and had been bomber pilots in World War II. Trevor loosened up a little while he drove and I, as usual, asked a thousand questions about the war, the States, flying huge aircraft and so on. He chuckled commenting on my inquisitiveness but seemed to enjoy relating his exploits.

The surest way to corrupt a youth is to instruct him to hold in higher esteem those who think alike than those who think differently.

—Friederich Nietzsche

We arrived at the lake and found the boat turned bottom up with the motor under it. It was an old, tired clinker of a dinghy. We managed to launch it in the wind. I pulled the starter cord, the venerable Johnson engine coughed, caught, and we knifed through the waves. I didn’t know the lake but headed straight to a point around which we anchored out of the wind, even as the rain hammered at us.

I had read that muskies were the fish of 10,000 casts, so did not expect much success. Nevertheless, I enjoyed watching Trevor expertly cast a large lure without a single backlash and retrieve it sputtering through the waves. Soon the rain started to seep through my patched rain jacket, one discarded by my brother-in-law. Trevor seemed to know where muskies lay and cast his large crank bait into the weeds just off a rocky shore.

Half an hour later, we were about to call it a day. We were soaked to the skin and the rain showed no signs of abating. To our wonderment, as his last cast hit the water, the crankbait vanished in a crashing swirl. I could hardly believe my eyes as the biggest, most beautiful fish I had ever seen vaulted out of the gray waves. It was a green- and gold-striped apparition with its evil sneering mouth gripping the lure.

Trevor, too, was taken aback and struck hard. The line came shooting back at him. The muskie had severed the leader—which I now know should have been woven steel, not merely thick monofilament— as muskies have razor-sharp teeth.

Trevor groaned and slumped over in disappointment and then unexpectedly yahooed for joy! In the past two years he had fished many days without ever hooking a muskie in Minnesota. We toasted the mighty fish with sweet creamy coffee in plastic cups Mom had provided, and he now babbled with excitement while I became the strong silent one. Then we headed for shore. Standing there was a tall dusky figure waiting to catch our boat at the dock, his dark eyes winkling twin beacons. It was Basil Philips, an old trapper and World War I marksman who would become a mentor to me.

“I’ve seen better looking drowned rats,” he chuckled. “Come on into my house. Katy has some soup on.” Katy, a handsome woman in her 50s, greeted us with a smile and bowls of homemade chicken soup—almost as good as my mom’s—that probably saved us from catching colds or worse.

The cabin, though a simple smoke-seasoned log structure, was well lit and cozy with a wood fire humming in the cast iron stove. Later, driving to Rat Lake, Trevor and I agreed that there wasn’t any place we would rather have been at that moment.

As we arrived at Rat Lake, Trevor asked how much I wanted to be paid for the day’s guiding, but I demurred arguing that it had been a very brief day. “And yet the best muskie fishing of my life,” said Trevor. “I notice you were eyeing the Ambassadeur reels. How ’bout you take one for your yeoman’s service today? You deserve it for leading me to my first muskie.”

I was stunned. From that moment on I began to believe that if I truly desired something and did something positive to get it, that it would come to pass. “I can’t do that,” I weakly objected, but Trevor brushed my objections aside and thrust the reel, now nicely ensconced in a beautiful leather case, into my hands. I have it to this day.

We said our goodbyes and he vowed to return the next summer to fish with me for muskies in “your secret lake.” He never did—another life lesson. Basil, on the other hand, became a longtime friend and catching muskellunge an obsession.

Basil was a natural storyteller and loved my questions and interest in his life. He had been raised in New Brunswick, joined the Canadian army as a teenager during the first world war, and went off to the see the world. He described the devastation and horror of fighting in the trenches in France but was able to escape the trenches because it became clear that he was an exceptional sharpshooter. From then on, he divided his time between serving as a sniper in the army targeting German officers and competing in military shooting contests, most notably the Bisley Army Operational Shooting Competition for the Queen’s Medal. I was in awe and never asked how he did in competition. It didn’t really matter. To me he was now a god among men.

The author’s father and grandfather fishing in Canada.

Basil got along very well with my folks and would often drop in on his way home whereupon my mom would ply him with homemade borscht—a delicious beet soup—some of which he would take home to Katy. He would regale us with war stories and others of his working for the forest service in British Columbia, especially as a fire tower warden high up in the mountains where he would watch myriad deer, moose, mountain lions and bighorn sheep pass by. To me it sounded like the perfect job, and he held a similar one for the local forest service where we would visit him on occasion.

But what really captured the fancy of my dad and me was his story of living as a trapper in a series of tiny cabins in the Royd Lake area due west of Rat Lake near the Manitoba border. During those winter sojourns on the trapline, he said he really missed Katy.

“One spring I was so happy to see her that the second thing I did was take off my snowshoes,” he quipped.

He described giant lake trout in Royd—a deep, mysterious, crystal-clear lake surrounded by dark spruce and white birch forests with spongy floors of fluorescent green moss that you could walk through carrying a canoe while herds of woodland caribou nervously melted into the woods to avoid you. It sounded like paradise to us and so on every occasion when we could afford it until his untimely death, Dad and I would get a fellow with a Cessna 180 on floats that my dad built parts for to take us to the lake. It was a sanctuary away from the cares of the world where we always caught fish and healed any wounds suffered in the real world.

I can still envision my dad puffing on his pipe in the misty morning as we trolled for fish, holding up the brown- and gold-red-spotted trout caught on the spoons that I had designed and Dad made in the machine shop, and him cleaning the fish by the water. It was a time when he was perfectly happy, as was I.

My dentist brother-in-law, Alex, had bought a station wagon and Basil was more than willing to let us borrow his boat and wouldn’t take any money for its rental. Two years later Basil told me Alex worked on his teeth for hours, to the point that Basil worried about how to pay for it all. Alex refused to take a penny.

I read everything I could lay my hands on about muskellunge. I learned that muskies were ravenous hunters, gorging themselves like pythons on the largest prey they can kill and consume, and then lie semi-dormant digesting for days, hence their “moodiness.” They had a reputation for being almost impossible to catch, but some rare days they could go on a rampage and every muskie in a lake would take any bait or lure. Unfortunately, that was a very rare phenomenon.

Preparing a shore lunch circa 1967.

Muskies were a mystery, and I loved mysteries, especially if conscientious, constant work led to their solution. I would give muskie seminars to Alex and Dad on what I had learned. Alex got the bug, but Dad was slightly dubious about catching a fish we had no interest in eating so he insisted we try cooking one should we get lucky.

I came to love the whole ritual: organizing my gear, especially the crankbaits with their propellers and the “Muskie Killers” with their treble trailing hooks covered in bucktail and feathers; checking the reels and especially the lines to make sure no twists turned to backlashes when we cast; and examining the leaders that we had learned to our dismay had to be steel, otherwise be sliced in two with a single snap of a mouth bristling with Wilkinson Sword-like razors.

The boat was old and much patched but made the low, comforting sounds when oars were set in place that only wooden boats can. It was usually evenings after work during the long and soft northern summer when we set out. We used the kicker only initially to get near a likely spot on the lake, spots such as “The Nursery,” an inner bay full of young fish; “The Reef,” which looked barren but held some giants in the waters around it; and “The Island” where one could also run into walleyes and was hence my dad’s favorite spot. Then we would get out the oars and the rower would troll while the two others cast ahead and to the sides of the boat. Sometimes we would see muskies, both large and small, following our lures to the boat. The hair would stand on the backs of our necks in anticipation of a strike that never happened.

Not for a whole year did any of us get a strike. But we persisted after muskies interspersed with fishing the high-yielding walleye lakes and, in the spring, the mystical Royd. Flat Lake also became a muskie-filled dream, though unfulfilled as I fantasized about monsters attacking my lure, turning that dream into a welcome nightmare.

More has been written about fishing than any topic other than mathematics—a fact librarians are fond of bringing up in cocktail conversation. And, probably because of its secretiveness and unwillingness, unlike its shamefully eager lesser cousin the northern pike who is so keen to take any lure or any bait, more has been told and written in North America about muskies than about any of the other glamorous fish of the world such as Atlantic salmon and steelhead. Men have devoted their adult lives to catching that one giant specimen, often just a lurking, cruising shadow they have on occasion spotted that haunts their dreams.

Basil passed along a great deal of local knowledge such as where large fish had been spotted and what lures worked when someone gleefully babbled upon returning to the dock about the fish he had hooked. He also kept a record of what weather prevailed when the fishing was good. Turns out cool, breezy days in the fall were best.

We received a call from Basil one September evening who said that the lake was going to be choppy and the weather nippy, but that the muskies seemed on the prowl. We sprang into action preparing lures, rods, lines, food and drink for the next day.

It didn’t disappoint.

The lake was too rough for us to anchor so, leaving behind the entrance to The Nursery, we trolled to The Reef. Suddenly, amazingly, all three of our rods dipped and, after a whole season of nothing, we had on a triple header. The fish fought hard and deep, like demons occasionally breaking the surface but mostly running unlike any pike we had ever hooked. The muskies were not big, ranging from 5 to 10 pounds, but we were beside ourselves with joy. We had actually hooked muskies, and every pass around The Reef brought one or two savage strikes. It was a bonanza and we chortled with joy landing more than a dozen before calling it a day in the late afternoon. Dad killed one muskie for Mom’s fish head soup. Unfortunately, it was delicious, but Dad said he would kill no more and I breathed a sigh of relief. We all agreed muskies were too valuable to be used only once.

One time while working for the forestry park service I brought a Wisconsin muskie fisherman whom I had befriended to Flat Lake, but only after he was sworn to secrecy. Roger Mueller, a wiry, tanned fellow who hailed from Oshkosh, was usually laconic but couldn’t hide his elation describing how he had finally caught a 20-pound muskie and had it mounted. I was appropriately impressed and told him I had never caught one more than 10 pounds but had seen some behemoths in my secret lake. His eyes lit up. After all, he had journeyed so far from home just to experience fishing that did not exist south of the true north.

It was a languid August evening, warm and welcoming with a very soft breeze riffling the water only slightly. We greeted Basil, launched his boat and headed out into the lake. As we pulled up to the entrance to The Nursery, the sun ignited a golden shimmering cast on the water and a loon let out its plaintive cry—almost a cliché in its apropos welcome for my guest. Moreover, I had seen a bulge about 50 feet off the bow.

“Cast there, Roger,” I said pointing to a lily pad where the bulge had since disappeared.

“No, Moishe, this is your lake. Show me how it’s done first.”

I didn’t hesitate, firing my giant Rapala floating balsawood sucker lure right over the entranceway to The Nursery. It landed with a noisy plop, and I started retrieving. We both gasped as a huge bow wave followed the lure and struck viciously, not grabbing it but merely sending it flying through the air toward me. We sat there for a moment in silence, gathering our thoughts. “Cast again,” said Roger in a hushed voice. And I did, again and again. Nothing.

“Your turn, Roger,” I said in a calm and unemotional voice disguising my disappointment. He had on a Musky Killer spin lure. It landed with a large splash, and he began retrieving. After not long, an explosion erupted, and a mighty fish breeched—the largest fish I had ever seen.

The fish ran then leapt again, then thrashed as Roger fought to recover line. From then on it was a slugfest. The fight lasted a half hour and, finally, a muskie as long as a paddle was alongside the boat. I couldn’t believe its size. I had no gaff, so I reached down and grabbed the lure with my pliers in one hand and the fish by the tail with the other and somehow swung it aboard. All hell broke loose, but I managed to pin it to the floorboards without harming it.

Roger managed a broad smile as he gasped at its enormous length and girth. It measured 49 inches and weighed at least 38 pounds we guessed. To my relief he agreed to let it go because he already had a trophy fish mounted. We watched in awe as it ambled casually back to its weed bed upon its release, probably cursing us for the inconvenience.

That fish seemingly broke the ice. I thereafter seldom went out on Flat Lake without hooking a muskie or at least getting some heart-stopping monsters to follow, but I never caught one the size of Roger Mueller’s. The lesson for me was that persistence pays off in knowledge and ultimately meaningful success. Knowledge and wisdom that you gain along the way never occur with instant success. Wisdom is the greatest reward—any one fish is not, regardless of its size.

This story is adapted from one of many in the book Blood Moon Over Rat Lake by Ehor Boyanowsky. In the book, Moishe, a young boy with a strange name grows up in the rough and ready environment of a northern mining town. As Moishe struggles to make sense of things, he finds comforting solace in the woods and lakes and develops a growing fascination with fishing and hunting. Along the way he becomes a committed reader and athlete. Life becomes a series of moral tests. His failure to help other outsiders troubles him and he vows to do better. He forms a close relationship with Jamey, a charismatic, strong and kind young man who grew up on a reservation and becomes a legendary bush pilot. Blood Moon Over Rat Lake is available online at sportingclassicsstore.com.