Part II

Of Ice and Men

I helped him get to his feet and got him moving toward camp. He walked like a crippled man. I quickly pulled the cord attached to my pack and it came up full of water. I turned it upside down and jammed the frame into the snow. I left the rifles and another gear where it lay and trotted after Niel. He stopped several times and looked back to see how I was doing. I yelled at him to keep moving. Though his hip boots were still filled with water, the walk to camp raised Niel’s core temperature enough to get much of his feeling back. I helped him get his boots off and the rest of his wet clothes. Luckily, Niel had a new Cocoon sleeping bag. A special survival bag, it inflates both top and bottom to provide maximum heat retention in extreme conditions. Once dry and inside the bag, Niel’s body temperature moved back to normal. As first-aid for his hypothermia, he refused any hot food for quite a while, explaining that the digestive process took blood away from one’s extremities.

The next day dawned bright and blue. We rested in camp, allowing both of us to recover and our stuff to dry. He told me matter-of-factly that he probably had another 15 minutes to go before total paralysis set in. We talked it over most of the day. I confessed that I never would have been able to live with watching him die. My final plan was to go in myself and hope he still had the strength to climb out on my shoulders and then pull me out. I was lighter, it may or may not have worked and I was thankful we didn’t have to try it.

Niel had fallen into a submerged stream that ran off the lake. For some reason, probably beavers, the stream had been diverted uphill toward the base of the ridge where we had walked. The snow had been hard enough to hold us in the morning but not in the afternoon. What had happened to Niel and nearly to me was a freak thing that would have happened to anyone traversing that route regardless of wisdom or experience as Niel’s was second to none. He asked me, if under the circumstances, I wanted to end the hunt. No, I told him. I’d been planning this for two years. Let’s just take it real slow and be careful. He was glad for that, that I chose to continue, but in the days ahead neither of us ever really trusted the ground we walked.

As time passed, we were able to put the incident behind us. We climbed the long hills on either side of camp and glassed the mountains lying beyond them. We began seeing bears. One large boar walked along the top of the ridge above us. It was over 500 yards and I missed him twice. We found his tracks later that day and Niel assessed him to square nine feet.

On May 16, Niel spotted a large bear on a distant mountain. Even at a mile and a half, Niel felt the bear was bigger than any we had seen. Too late in the afternoon for a stalk, we watched the grizzly for the rest of the day. Before long, a smaller sow appeared next to him. A good sign. Niel knew that since the boar was with a sow and most certainly breeding her, he would likely stay there. We planned a stalk for early the next day.

The weather in the morning was good. We left camp at 5:30 a.m. with the sun still below eastern mountains. It took several hours to snowshoe the low ridges and frozen ravines. At each high point we stopped and found the bears a little farther up the mountain. We dropped the nonessential gear from our packs and moved on. The going became difficult.

Once at the mountain’s base, we learned our problem would be the wind. Using the most direct route up a stepped razorback, the bears would not be able to see us but would have our scent. Angling up to them was impossible — the slopes off each side of the razorback were full of deep, potentially avalanche snow. Our only possibility was to climb the high western ridge which lay mostly free of snow, but was very steep and presented a much longer climb — a huge clockwise circle of almost a mile — to get above and downwind of the bears.

Niel and I soon dropped our packs and modified the strategy. I would try to get above the bears and he would wait part-way up, near the edge of the snow-covered ridge. If the bears moved down off the top, Niel would attempt to spook them back up toward me.

I left everything, emptying my pockets of all but my cartridges. It was a steep climb, and much of the time I slung my rifle and went on all fours. Halfway up, I spotted the bears on the ridge 800 yards above me. They looked down in my direction, but I couldn’t tell if they actually saw me or not. There was nothing to do but keep going.

I moved farther across the face of the slope, out of the bears’ sight-line, and continued to climb. In another half-hour I was glassing the animals from above, but still too far for a shot. There was ankle-deep snow at the top. I crept across the weak crust, one hand in it, making noise at every step. I worked to a small rockpile that offered an excellent rest, but the range was still about 300 yards. There was another small rock pile downslope about 70 yards closer to the bears. I moved toward it, soon hitting loose scree that I sent clattering with every step. Too close to afford any noise, I hugged my rifle lengthwise to my chest and slowly rolled the last 50 yards down the scree.

When I made it to the rock pile, I was about 225 yards from the bears. In the clear mountain air it seemed I could almost touch them. They stood together milling around, too close to each other for me to take a proper shot. I waited, watching them. It was then I noticed the smaller bear nose around behind the larger, dark one. The small bear was the boar! I was suddenly sure of it. The sow was well over nine feet, and a legal trophy by anyone’s measure.

She was old but still fertile and would probably be able to produce cubs for years yet. It was for that reason I chose to kill the boar. Though smaller, his pelt was stunning, a rich blonde that the Eskimos called Toklat. It was day seven with the snow conditions deteriorating and probably my last chance. The wind rushed over me as I lay flat, and the same voice started.

Push an extra one in the chamber so you got four. Lay four more out in easy reach. This could be perfect if you do it right or Custer’s Last Stand if you blow it.

Suddenly, the bears broke apart and rushed toward me. My heart hammered and I pushed the safety off. Just as suddenly they were walking again, some ursine ritual playing out, and I collected myself.

Good, good, that last little romp bought you forty yards. Hold on the boar and wait til he walks clear. There he goes, there he goes, turn now, I need to see your shoulder.

At the shot the bears scrambled. The male froze, arguing with the unexplained collision against his side. I heard the shot echo off the next mountain and cycled the bolt, looking for the sow, I found her at nine-power, rage in her enormous face, indignation.

There she is, coming for me. Don’t do it, big girl. Save yourself.

At 90 yards, the gargantuan ripple of the sow veered off and ran over the ridge.

That a girl, don’t come back. I ain’t worth it. You must go eight hundred pounds.

Then it’s the boar, shrugging off the shot, snapping and snarling up the ridge at the thing that hit him. Hair up, growing in the scope, there is no fear in the boar’s face, none at all.

Come on, son. Come at me, I knew you would, It’s just you and me up here, you beautiful bastard.

At seventy yards the boar turns and follows the sow. He gives me his shoulder, the barrel swinging and drops at the shot.

Don’t move. Stay on that boar, he may get up, Watch that ridgeline every few seconds in case the sow comes back. No, no sign of her. Just wait, just wait. No, she’s not coming back and the boar’s not moving.

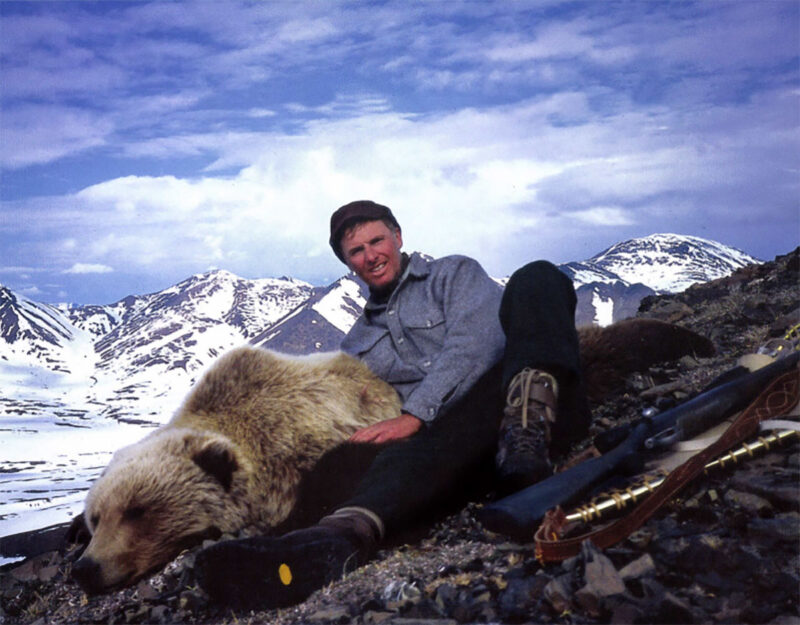

Load two and work down to the bear. Don’t take your eyes off him. Here comes Niel, on his way up, he saw the whole thing through the glasses. Don’t relax, that sow could still come. Put one more in the boar on the way down. You did it. The sow got away clean. You got it made. Go down now and sit with your bear . . .

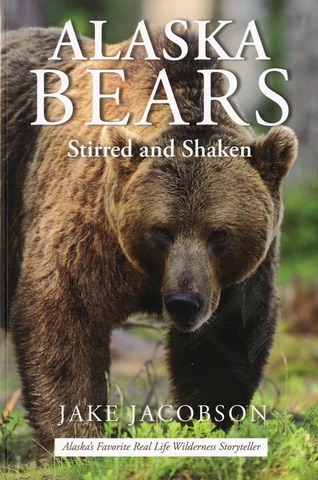

A collection of 24 stories describing Jake Jacobson’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska.

A collection of 24 stories describing Jake Jacobson’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska.

Jake came to Alaska in 1967 and among other things, he holds Alaska Master Guide license #54, a commercial Pilot license, a 100Ton Mariner’s license, is a Benefactor Life member of the NRA and has operated from his eighty acre private land located 155 miles north of the Arctic Circle since 1969. Buy Now