Part I

Of Ice and Men

Just being in grizzly bear country gives one enough to stay awake about. Most dangerous of all North American game, the grizzly across a land that can present an equal peril. Western Alaska’s overwhelming of isolated hills and drainages — empty, wet — can be unpretty and less than forgiving.

“This country will consume you,” my friend David Hughes remarked to me. We were looking out over an enormous alder brush basin where we’d spent the last five hours, mostly in search of moose. It was a prescient comment.

On May 10, a bush plane dropped me on a frozen mountain fake 75 miles southeast of the village of Aniak. Waiting by the small dome tent that would be home for the 10-day bear hunt was my guide Niel Webster, president of the Alaska Professional Hunters Association. With over 25 years’ experience in the bush, Niel was capable and well-organized. A bearded, burly 260 pounds, he seemed right out of central casting for the role. To back me up, he carried a big .375 H&H which he shot extremely well. His friendliness and belligerent humor put me at ease, and I felt confident in his ability to keep us out of trouble.

We spent that first night complaining about the lousy freeze-dried food and filling each other in on our backgrounds. We were camped on an island of dry tundra, a circle about 20 yards across and the only bare ground in the lake basin. The sun had melted the snow from the southern slopes, but on the north faces it was quite deep and in avalanche condition in many areas.

During the night, the temperature dropped below freezing and the snow had hardened to what Niel referred to as white asphalt. It was easy walking, only an hour or so out to our glassing area at the north side of the basin. We didn’t see much that first day, only a wolverine and some ptarmigan. About 5:30 p.m., Niel suggested we begin the trip back which would take much longer. The sun had softened the snow and it was tough snowshoeing with our heavy packs and gear.

Camp was about a half-mile away when the long arctic dusk began. Abruptly, Niel sank in the snow to his waist. I had been trailing him. I moved up and helped him remove his rifle and pack. As I did, I slipped in up to my thigh. Figuring it was just soft snow or an air pocket, I leaned back and pulled free. When I looked up, the snow around Niel gave away and he dropped out of sight. He yelled something in a swirl of white, and his fall stopped momentarily, then resumed as he crashed through another layer, continuing 12 feet down into a narrow, water-filled chasm.

Horrified, I watched him splash into the icy water. When he was able to stand up, the water came up to his waist. That it wasn’t over his head was the only good luck we had.

“Get back,” Niel was yelling. “It’s rotten snow up there.”

Cursing, I stepped back.

“There’s a rope in my pack.”

“Where,” I screamed.

“In the side pocket. Already his voice was tight with the cold pain of the water coming on.

I tore the pack apart. I couldn’t find it.

“What pocket?”

“I don’t know. One of the sides.” His hip-boots were now completely full.

I watched my hands rifle the pockets. It was as though they belonged to someone else. I noticed the time on my watch. Ten minutes to eight. We had to work fast; he could easily freeze to death in that water. When I found the pack of nylon rope, I slit the plastic wrap off with my knife and doubled it before I lowered it down to Niel.

He wrapped it around his back and under his arms.

“Okay,” he said.

I moved a safe distance from the hole and dug the cleats of my snowshoes into the snow.

“Here goes,” I said, sidestepping. I brought Niel up a few feet but felt him catch on something.

“Let me back down,” he said and I eased him back to the freezing water.

Hands freezing, Niel remembered a pair of neoprene gloves in his pack and I threw them down. With the gloves, he was able to get his left snowshoe off and work it into the glacial ice at eye level. He then dug a narrow shelf near his waist to use as a step. It was difficult in the narrow space.

When Neil was ready, I side-stepped him up again, but he couldn’t get purchase on anything to hold himself while I could grab him. We tried several times.

“Niel, listen to me. This isn’t working. I’m going to run to camp and hit the ELT (emergency locator transmitter). We’ll get a helicopter in here with a hoist.

Niel shook his head.

“Nearest chopper’s two hours from here. I’m in severe hypothermia now. By the time you get back I won’t have the strength to move.”

“OK, man. OK. We’ll get you out of there.”

I stepped into the double rope, worked it over my shoulder and side-stepped his 260-pound frame until his head was almost out. But again, there was no way to hold him there. There were no trees or alder brush or anything to tie the rope to — nothing around us but snow.

“It’s no good,” he said. Reluctantly, I lowered him back down. I crawled to the hole to look at him. When I did, a bit of snow gave way and covered his head and shoulders. He’d been in the water more than 20 minutes.

“How do you feel?”

“I don’t have any feeling below the waist.”

I eased back from the weak snow at the lip.

“Under no circumstances can I fall in,” I said. “If I do, we’re both dead.”

“I know it,” Niel’s voice came flatly. “I just don’t know what I can do to get out.”

I felt myself going into a kind of shock then, a strange state of being. It was a feeling of utter helplessness, of being unable to keep a man alive who was only 12 feet away.

We were losing light. I frantically searched the dimness for fallen trees, tangles of brush, any possible thing that I could shove down the hole for Niel to climb on. But the hillsides and the basin were barren. From inside, a voice that knew me well admonished me.

Think, boy. There’s no time left. You better make something happen.

I looked at the gear scattered in the snow. I grabbed Niel’s.375, unloaded it and held it over the hole, thinking laid flat, Niel could use it to hold onto. No good, the snow was too rotten around the rim. I ran back to the gear looking at each article of spare clothing that I might be able to tie together or something, but couldn’t come up with anything useful.

If there’s an answer it has to be right in front of you. In the gear. Something you can do with the gear. My pack!

I ran to my pack and emptied it in the snow. Using a piece of cord, I lowered it to Niel.

“Try to lean the pack against the bottom and the side. Use the frame like a step ladder. Try that.”

Niel looked up at me as the pack went down. The sight of him down there in the dark with no way out was awful. I watched him position the pack. His mobility was almost gone. His motions were slow and stiff. I talked to him, lying really, telling him we’d get him out this time with no problem. He only told me to be careful walking on either side of the hole as the fissure ran in both directions as far as he could see. Trapped in a claustrophobic ice tomb, Niel was still concerned with my continued safety. He exhibited no fear or hopelessness, a true professional. In the half-hour he’d been in the water, the temperature had dropped and the snow around me was beginning to freeze again.

Wearily, he told me that the rope had dug in the snow at the lip each time I had raised him. I glanced at the snowshoe he’d thrown out. I seized it and began digging a 45-degree slope into the lip of the hole. I hoped it would give me a more direct pull. I dug carefully. If I went in, they wouldn’t find either of us until spring. As I dug, much snow dropped down on Niel. He grimaced, but stood calmly. When I had dug as far as I dared, I passed the snowshoe to him and he lethargically dug until the slope reached him. He then passed the snowshoe back to me.

Every second counted now. To be able to use his arms more effectively, this time Niel ran the rope under his butt. I stepped back into the rope, draped it over my shoulder and began to side-step. We both knew this was our last chance.

I hauled as Niel stepped up on the pack frame. He told me to stop. He found the shelf he’d made with his left knee. I started him up again and simultaneously he worked his elbow onto the wedged-in snowshoe. He allowed me to raise him, carefully maneuvering the snowshoe he still wore on his right foot so that it wouldn’t hang up. I hauled and his head came up, then his shoulders. I didn’t know it then, but his other knee had made it onto the wedged in snowshoe.

I hauled as Niel stepped up on the pack frame. He told me to stop. He found the shelf he’d made with his left knee. I started him up again and simultaneously he worked his elbow onto the wedged-in snowshoe. He allowed me to raise him, carefully maneuvering the snowshoe he still wore on his right foot so that it wouldn’t hang up. I hauled and his head came up, then his shoulders. I didn’t know it then, but his other knee had made it onto the wedged in snowshoe.

For the first time in 30 minutes, he spoke to me above the snow. “Grab me,” he said. “I’m holding myself.”

I gently released tension on the rope and moved toward him. I had his wrist, and he took hold of mine. Then I pulled him up and across the frozen snow.

“I’m clear.”

“Thank God,” I said.

End of Part I

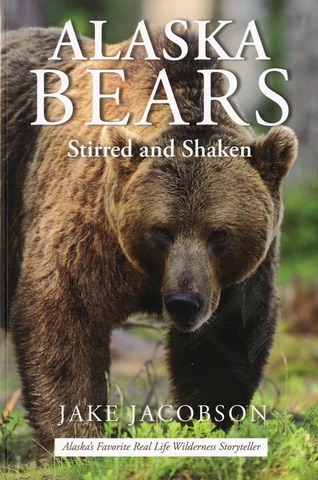

A collection of 24 stories describing Jake Jacobson’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska.

A collection of 24 stories describing Jake Jacobson’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska.

Jake came to Alaska in 1967 and among other things, he holds Alaska Master Guide license #54, a commercial Pilot license, a 100Ton Mariner’s license, is a Benefactor Life member of the NRA and has operated from his eighty acre private land located 155 miles north of the Arctic Circle since 1969. Buy Now