One year in Saskatchewan an early October snowstorm interrupted the grain harvest. I was hunting waterfowl with outfitter Bentley Coben, who stages out of Tessier, when more than a foot of wet October snow interrupted our plans.

The birds were desperate to feed, and we were desperate to get to them. Back roads, tractor trails, fields, heck, even the farm yards, were all clogged by snow—a wet snow that built up on tires, caked on the bottoms of trucks and decoy trailers, fell and melted on the decoys and made them glisten.

Plans change, and Bentley had to make some rapid adjustments to his: how to get five hunters, a guide, himself, gear, blinds, and decoys into fields that the birds were using; how to find fields that we could reach; how to get the equipment into the fields without leaving deep ruts in the very wet soil; how not to offend his worried farmers with those ruts; even how to get out of his driveway to scout. Lots to think about. We were in good hands.

I come from New Hampshire, so I was prepared for all sorts of weather—waterproof clothing for both hot and cold temps, waterproof boots, heavy and light socks, a waterproof knit hat as well as my usual bill hat. This was my tenth time hunting in Saskatchewan, and I’d encountered all temperatures and conditions before. Also, being from New Hampshire mountain country, I am suspicious of October weather, especially weather several hundred miles north and 1,500 miles west of me.

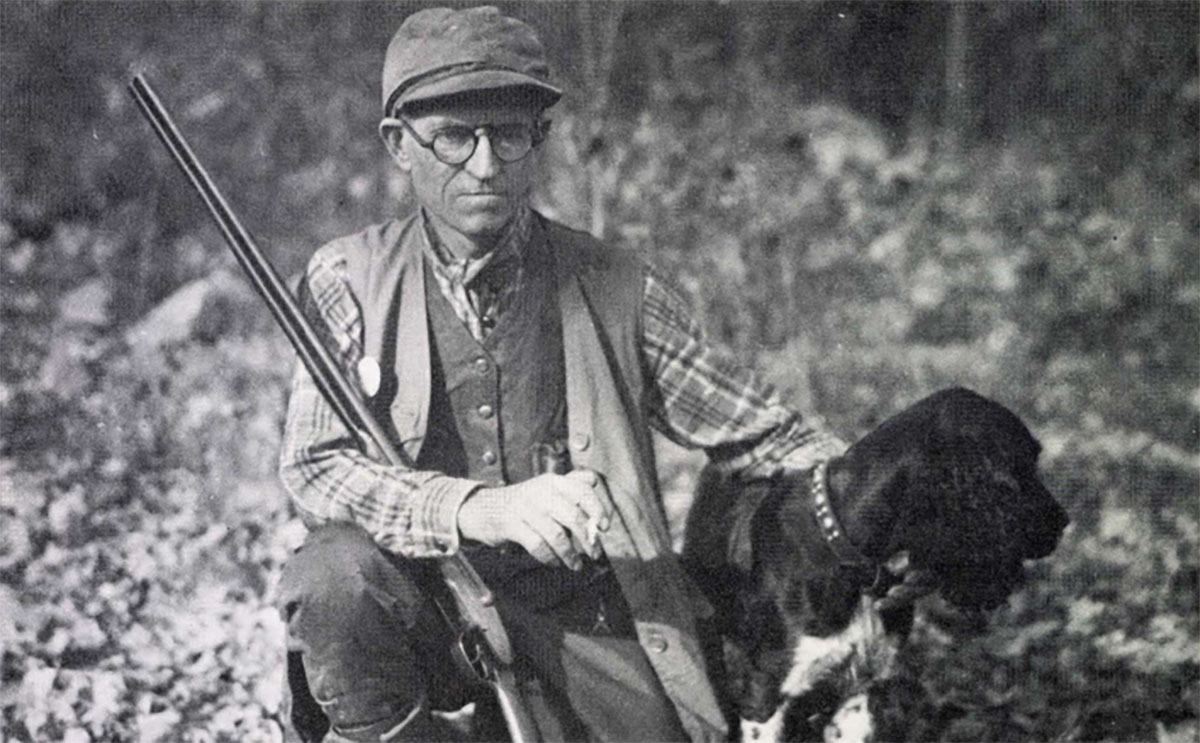

Ready to roll some birds.

I was ready, but my hunting companions, all from the Carolinas, were not. They were waterproof, but they were not cold-proof. They needed warm hats, layers of clothing, warm socks and boots. Bentley dug into his storeroom—the one I swear goes into another dimension—and equipped them all. And at 5 a.m., just before we left for the hunt, no less! It was a wild 15 minutes—fitting and trading clothing, boots and hats, filling the thermos with hot coffee, grabbing snacks and putting on white pants, jackets or overalls, all from the storeroom.

Then to the trucks and four-wheelers for a convoy to the area Bentley had scouted yesterday. Slosh, mud, ice, wet snow, water—we slid through them all for 20 miles. Those Saskatchewan boys can drive! An all-terrain vehicle came off its perch and carefully hauled the decoy trailer into the field, leaving next to no ruts. The trucks stayed off the field. We hunters walked in, carrying shotguns and blind bags, slipping in the mud and slosh, at times kicking through 12 inches or more of snow.

A wet snow was still falling, but getting home was a problem for later in the day. We were here with guns, blinds and decoys, and there were already birds in the air.

We set up fast. Seven knowledgeable people make short work of decoy spreads, even large ones. Lots of goose decoys and two robo-ducks; figure out the wind; set up with the wind at our backs and get ready. Bentley had barely left the field with the ATV and trailer when a small group of pintails tried to settle in. Colin called the shot at 15 yards, and the five of us wiped out a flock of seven sprigs. This was in-your-face shooting. Those birds were hungry and anxious to feed.

Here’s a thought: Birds in the air keep you warm.

That morning we were sitting in chairs. Dressed in white and blending into the mist and snow, we watched flocks of hungry geese and ducks come into our rig, waited for the call, and shot seated above the snow and slush. Canadas, specks, a few snows, mallards, and pintails came in five- to ten-minute intervals for two hours. After the first 40 minutes we rotated hunters, shooting two at a time. One took the left side, the other the right—fun to see birds fall and know that you hit them (or missed), and know that two hunters were not shooting the same bird. Colin sat behind us and called the rotation and the shot. He grinned a lot that morning. So did we.

It wasn’t long before the sky was dark with birds instead of clouds.

The snow stopped. The day cleared. The birds stopped flying. Hungry and happy, we went home for breakfast: eggs, pancakes, bacon, and coffee, followed by a nap.

Late that afternoon we went back to the same area. The mist had cleared and the sun was out. The melt had started. More slosh and a wet cold that cut through all your layers. Visibility was too good to set up in chairs in the open, so we used blinds. The birds were still hungry and came out to feed, this time more cautiously—we had educated the early flocks. We had many passing and flaring shots. If the birds came too close, they’d look right down at us. I swear one suzie winked at me.

We huddled as close to the camo as we could, listened to Colin’s description of what was happening, fought the need to look, and waited for the call. Colin is good; when the call came we knew the birds were in range. Towards dark two big flocks of mixed pintails and mallards came into the decoys. The light was fading, so they could not pick us out, but they were skylined. Colin made the call, and birds fell out of the sky—a great ending to an unusual October day.

When it comes to actually shooting ducks and geese over water, the action is on the small places – the inland lakes, the ponds and potholes, the floodings and creeks and backwaters. Day in and day out, that’s where the ducks are, and that’s where Chris Smith takes you.

When it comes to actually shooting ducks and geese over water, the action is on the small places – the inland lakes, the ponds and potholes, the floodings and creeks and backwaters. Day in and day out, that’s where the ducks are, and that’s where Chris Smith takes you.

However, each of these places requires a separate technique, alternate decoys spreads and calling concepts, and different gear to use. He tells you how to approach each type of hunting for the weather and conditions. He knows when and when not to call. He describes the skills a good waterfowl dog needs to know for each place, things he’s taught his succession of Labrador retrievers over the years. Buy Now