I left long before daylight, alone but not lonely. Sunday-morning stillness filled the big city. It was so quiet that I heard the whistle of duck wings as I unlocked the car door. There would be ducks leaving Lake Michigan. A fine sound, that, early of a morning. Wild ducks flying above the tall apartments and the sprawling factories in the dark, and below them people still asleep, who knew not that these wild kindred were up and about early for their breakfast.

The wingbeats I chose to accept as a good omen. And why not? Three weeks of doing what I wished to do lay before me. It was the best time, the beginning of the last week in October. In the partridge woods I would pluck at the sleeve of reluctant Indian summer, and from a duck blind 400 miles to the north I would watch winter make its first dash south on a northwest wind.

I drove through sleeping Milwaukee. I thought how fine it would be if, throughout the year, the season would hang on dead center, as it often does in Wisconsin in late October and early November. Then one may expect a little of everything – a bit of summer, a time of falling leaves, and finally that initial climatic threat of winter to quicken the heart of a duck hunter, namely me.

To be sure, these are mere hunter’s dreams of perpetual paradise. But we all do it. And, anyway, isn’t it fine to go on that early start, the car carefully packed, the day all to yourself to do with as you choose?

Lunch Time by J.C. Lyendecker – Courtesy The Remington Collection.

On the highway I had eyes for my own brethren of the varnished stock, the dead-grass skiff, the far-going boots. Cars with hunting-capped men and cars with dimly outlined retrievers in backseats flashed by me. I had agreed with myself not to go fast. The day was too fine to mar with haste. Every minute of it was to be tasted and enjoyed, and remembered for another, duller day. Twenty miles out of the big city a hunter with two beagles set off across a field toward a wood. For the next ten miles I was with him in the cover beyond the farmhouse and up the hill.

Most of that still, sunny Sunday I went past farms and through cities, and over the hills and down into the valleys, and when I hit the fire-lane road out of Loretta-Draper I was getting along on my way. This is superb country for deer and partridge, but I did not see many of the latter; this was a year of the few, not the many. Where one of the branches of the surging Chippewa crosses the road I stopped and flushed mallards out of tall grass. On Clam Lake, at the end of the fire lane, there was an appropriate knot of bluebills.

The sun was selling nothing but pure gold when I rolled up and down the hills of the Namakagon Lake country. Thence up the blacktop from Cable to the turnoff at Drummond, and from there straight west through those tremendous stands of jackpine. Then I broke the rule of the day. I hurried a little. I wanted to use the daylight. I turned in at the mailboxes and went along the back road to the nameless turn-in – so crooked and therefore charming.

Old Sun was still shining on the top logs of the cabin. The yard was afloat with scrub oak leaves, for a wind to blow them off into the lake must be a good one. Usually it just skims the ridgepole and goes its way. Inside the cabin was the familiar smell of native Wisconsin white cedar logs. I lit the fireplace and then unloaded the car. It was near dark when all the gear was in, and I pondered the virtues of broiled ham steak and baking powder biscuits to go with it.

I was home, all right. I have another home, said to be much nicer. But this is the talk of persons who like cities and, in some cases, actually fear the woods.

There is no feeling like that first wave of affection which sweeps in when a man comes to a house and knows it is home. The logs, the beams, the popple kindling snapping under the maple logs in the fireplace. It was after dark when I had eaten the ham and the hot biscuits, these last dunked in maple syrup from a grove just three miles across the lake as the crow flies and ten miles by road.

When a man is alone, he gets things done. So many men alone in the brush get along with themselves because it takes most of their time to do for themselves. No dallying over division of labor, no hesitancy at tackling a job.

There is much to be said in behalf of the solitary way of fishing and hunting. It lets people get acquainted with themselves. Do not feel sorry for the man on his own. If he is one who plunges into all sorts of work, if he does not dawdle, if he does not dwell upon his aloneness, he will get many things done and have a fine time doing them.

After the dishes I put in some licks at puttering. Fifty very-well-cared-for decoys for diving ducks and mallards came out of their brown sacks and stood for anchor-cord inspection. They had been made decent with touchup paint months before. A couple of 12-gauge guns got a pat or two with an oily rag. The contents of two shell boxes were sorted and segregated. Isn’t it curious how shells get mixed up? I use nothing but 12-gauge shells. Riding herd on more than one gauge would, I fear, baffle me completely.

I love to tinker with gear. It’s almost as much fun as using it. Shipshape is the phrase. And it has got to be done continuously, otherwise order will be replaced by disorder, and possibly mild-to-acute chaos.

There is a school which holds that the hunting man with the rickety gun and the out-at-elbows jacket gets the game. Those who say this are fools or mountebanks. One missing top button on a hunting jacket can make a man miserable on a cold, windy day. The only use for a rickety shotgun is to blow somebody to hell and gone.

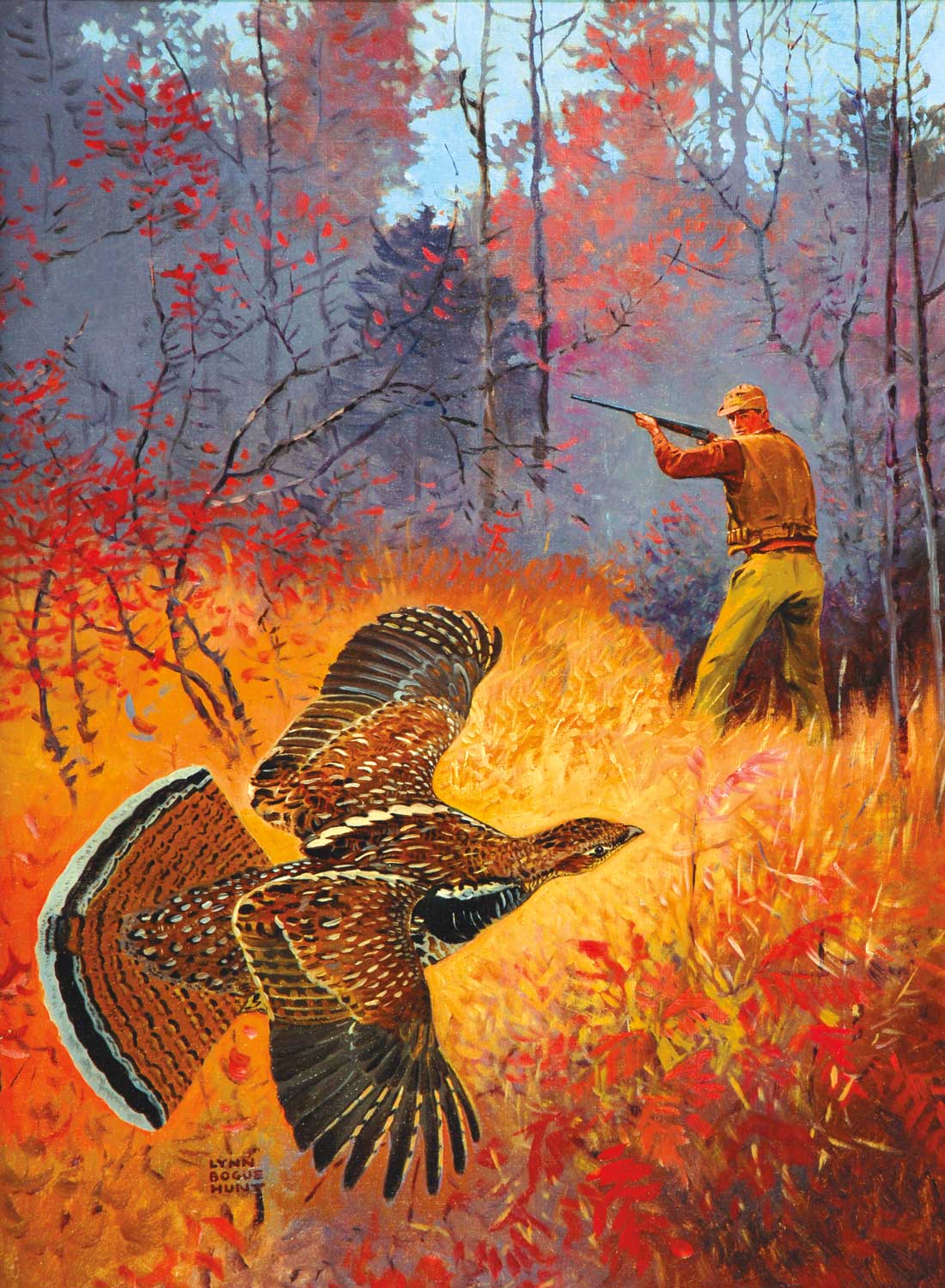

Lynn Bogue Hunt – Courtesy Copley Fine Art Auctions.

I dragged a skiff down the hill to the beach, screwed the motor to it, loaded the decoys and did not forget to toss in an ax for making a blind and an old shell box for a seat. I also inspected the light and found it good. It was not duck weather, but out there in the dark an occasional bluebill skirled.

I went back up the hill and brought in fireplace wood. I was glad it was not cold enough to start the space heater. Some of those maple chunks from my woodpile came from the same sugar bush across the lake that supplied the hot biscuit syrup. It’s nice to feel at home in such a country.

How would you like to hole up in a country where you could choose, as you fell asleep, between duck hunting and partridge hunting, between smallmouths on a good river like the St. Croix or trout on another good one like the Brule, or between muskie fishing on the Chippewa flowage or cisco dipping in the dark for the fun of it? Or, if the mood came over you, just a spell of tramping around on deer trails with a hand ax and a gunnysack, knocking highly flammable pine knots out of trees that have lain on the ground for 70 years? I’ve had good times in this country doing nothing more adventurous than filling a pail with blueberries or a couple of pails with wild cranberries.

If you have read thus far and have gathered that this fellow MacQuarrie is a pretty cozy fellow for himself in the bush, you are positively correct. Before I left on this trip the boss, himself a product of this same part of Wisconsin and jealous as hell of my three-week hunting debauch, allowed, “Nothing to do for three weeks, eh?” Him I know good. He’d have given quite a bit to be going along.

Nothing to do for three weeks! He knows better. He’s been there, and busier than a one-armed paperhanger.

Around bedtime I found a seam rip in a favorite pair of thick doeskin gloves. Sewing it up, I felt like Robinson Crusoe, but Rob never had it that good. In the Old Duck Hunters we have a philosophy: When you go to the bush, you go there to smooth it, and not to rough it.

And so to bed under the watchful presence of the little alarm clock that has run faithfully for 20 years, but only when it is laid on its face. One red blanket was enough. There was an owl hooting, maybe two wrangling. You can never be sure where an owl is, or how far away, or how many. The fireplace wheezed and made settling noises. Almost asleep, I made up my mind to omit the ducks until some weather got made up. Tomorrow I’d hit the tote roads for partridge. Those partridge took some doing. In the low years they never disappear completely, but they require some tall walking, and singles are the common thing.

No hunting jacket on that clear, warm day. Not even a sleeveless game carrier. Just shells in the pockets, a fat ham sandwich and Bailey Sweet apples stuck into odd corners. My game carrier was a cord with which to tie birds to my belt. The best way to do it is to forget the cord is there until it is needed; otherwise the Almighty may see you with that cord in your greediness and decide you are tempting Providence and show you nary a feather all the day long.

Bluebills by Lynn Bogue Hunt – Courtesy The Remington Collection.

By early afternoon I had walked up seven birds and killed two, pretty good for me. Walking back to the cabin, I sort of uncoiled. You can sure get wound up walking up partridge. I uncoiled some more out on the lake that afternoon building three blinds, in just the right places for expected winds.

This first day was also the time of the great pine-knot strike. I came upon them not far from a thoroughfare emptying the lake, beside rotted logs of lumbering days. Those logs had been left there by rearing crews after the lake level had been dropped to fill the river. It often happens. Then the rivermen don’t bother to roll stranded logs into the water when it’s hard work.

You cannot shoot a pine knot, or eat it, but it is a lovely thing and makes a fire that will burn the bottom out of a stove if you are not careful. Burning pine knots smell as fine as the South’s pungent literwood. Once I gave an artist a sack of pine knots and he refused to burn them and rubbed and polished them into wondrous, birdlike forms, and many called them art. Me, I just pick them up and burn them.

Until you have your woodshed awash with pine knots, you have not ever been really rich. By that evening I had made seven, two-mile round trips with the boat and I estimated I had almost two tons of pine knots. In even the very best pine-knot country, such as this was, this is a tremendous haul for one day; in fact, I felt vulgarly rich. To top it off, I dug up two husky boom chains, discovered only because a link or two appeared above ground. They are mementos of the logging days. One of those chains was partly buried in the roots of a white birch some 50 years old.

No one had to sing lullabies to me that second night. The next day I drove 18 miles to the quaggy edge of the Totogatic flowage and killed four woodcock. Nobody up there hunts them much. Some people living right on the flowage asked me what they were.

An evening rite each day was to listen to weather reports on the radio. I was impatient for the duck blind, but this was Indian summer and I used it up, every bit of it. I used every day for what it was best suited. Can anyone do better?

The third day I drove 35 miles to the lower Douglas County Brule and tried for one big rainbow, with, of course, salmon eggs and a Colorado spinner. I never got a strike, but I love that river. That night, on Island Lake eight miles from my place, Louis Eschrich and I dip-netted some eating ciscoes near the shore, where they had moved in at dark to spawn among roots of drowned jackpines.

There is immense satisfaction in being busy. Around the cabin there were incessant chores that please the hands and rest the brain. Idiot work, my wife calls it. I cannot get enough of it. Perhaps I should have been a day laborer. I split maple and Norway pine chunks for the fireplace and kitchen range. This is work fit for any king. You see the piles grow, and indeed the man who splits his own wood warms himself twice.

On Thursday along came Tony Burmek, Hayward guide. The big crappies were biting in deep water on the Chippewa flowage. There’d be nothing to it. No, we wouldn’t bother fishing muskies, just get 25 of those crappies apiece. Nary a crappie touched our minnows, and after several hours I gave up, but not Tony. He put me on an island where I tossed out half-a-dozen black-duck decoys and shot three mallards.

When I scooted back northward that night, the roadside trees were tossing. First good wind of the week. Instead of going down with the sun, Old Wind had risen, and it was from the right quarter, northwest. The radio confirmed it, said there’d be snow flurries. Going to bed that windy night, I detected another dividend of doing nothing – some slack in the waistline of my pants. You ever get that fit feeling as your belly shrinks and your hands get callused?

By rising time of Friday morning the weatherman was a merchant of proven mendacity. The upper pines were lashing and roaring. This was the day! In that northwest blast the best blind was a mile run with the outboard. Only after I had left the protecting high hill did I realize the full strength of the wind. Following waves came over the transom.

Before full light I had 40 bluebill and canvasback decoys tossing off a stubby point and 11 black duck blocks anchored in the lee of the point. I had lost the 12th black duck booster somewhere, and a good thing. We of the Old Duck Hunters have a superstition that any decoy spread should add up to an odd number.

Plenty of ducks moved. I had the entire lake to myself, but that is not unusual in the Far North. Hours passed and nothing moved in. I remained long after I knew they were not going to decoy. All they had in mind was sheltered water.

Next time you get into a big blow like that, watch them head for the lee shore. This morning many of them were flying north, facing the wind. I think they can spot lee shores easier that way, and certainly they can land in such waters easily. In the early afternoon when I picked up, the north shore of my lake – seldom used by ducks because it lacks food – held hundreds of divers.

Sure, I could have redeployed those blocks and got some shooting. But it wasn’t that urgent. The morning had told me that they were in, and there was a day called tomorrow to be savored. No use to live it up all at once.

Because I had become a pine-knot millionaire, I did not start the big space heater that night. It’s really living when you can afford to heat a 20-by-30-foot living room, a kitchen and a bedroom with a fireplace full of pine knots.

The wind died in the night and by morning it was smitten-cold. What wind persisted was still northwest. I shoved off the loaded boat. Maybe by now those newcomers had rested. Maybe they’d move to feed. Same blind, same old familiar tactics, but this time it took twice as long to make the spread because the decoy cords were frozen.

A band of bluebills came slashing toward me. How fine and brave they are, flying in their tight little formations! They skirted the edge of the decoys, swung off, came back again and circled in back of me, then skidded in, landing gear down. It was so simple to take two. A single drake mallard investigated the big, black, cork duck decoys and found out what they were. A little color in the bag looks nice.

I was watching a dozen divers, redheads maybe, when a slower flight movement caught my eye. Coming dead in were 11 geese, blues, I knew at once. I don’t know whatever became of those redheads. Geese are an extra dividend on this lake. Blues fly over it by the thousands, but it is not goose-hunting country. I like to think those 11 big black cork decoys caught their fancy this time. At 25 yards the No. 6s were more than enough. Two of the geese made a fine weight in the hand, and geese are always big guys when one has had his eyes geared for ducks.

The cold water stung my hands as I picked up. Why does a numb, cold finger seem to hurt so much if you bang it accidentally? The mittens felt good. I got back to my beach in time for the prudent duck hunter’s greatest solace, a second breakfast. But first I stood on the lakeshore for a bit and watched the ducks, mostly divers, bluebills predominating, some redheads and enough regal canvasback to make tomorrow promise new interest. The storm had really brought them down from Canada. I was lucky. Two more weeks with nothing to do.

Nothing to do, you say? Where’d I get those rough and callused hands? The windburned face? The slack in my pants? Two more weeks of it . . . Surely, I was among the most favored of all mankind. Where could there possibly be a world as fine as this?

I walked up the hill, a pine-knot millionaire, for that breakfast.

Editor’s Note: “Nothing to do for Three Weeks” is from Old Duck Hunters and Other Drivel, published in 1998. It is reprinted courtesy of Tom Petri and Willow Creek Press.