The bumper sticker read: A bad day fishing is better than a good day at work.

I was sitting in bumper-to-bumper traffic wondering how I had allowed myself to get in such a frustrating situation. Like all of the other miserable souls around me, I was growing more impatient with every passing moment. That’s when the bumper sticker caught my eye. It stood out like a sore thumb, and no flashing neon sign could have grabbed my attention more thoroughly at that particular moment in my life. It was a common quote that I’d seen on bumper stickers and read often in other printed material, but that day the sheer power of that short sentence was like a drink of cool water to a man in the desert.

The bumper sticker read: A bad day fishing is better than a good day at work. Next to those words was a sketch of a man holding a rod that was doubled over as he netted a fish.

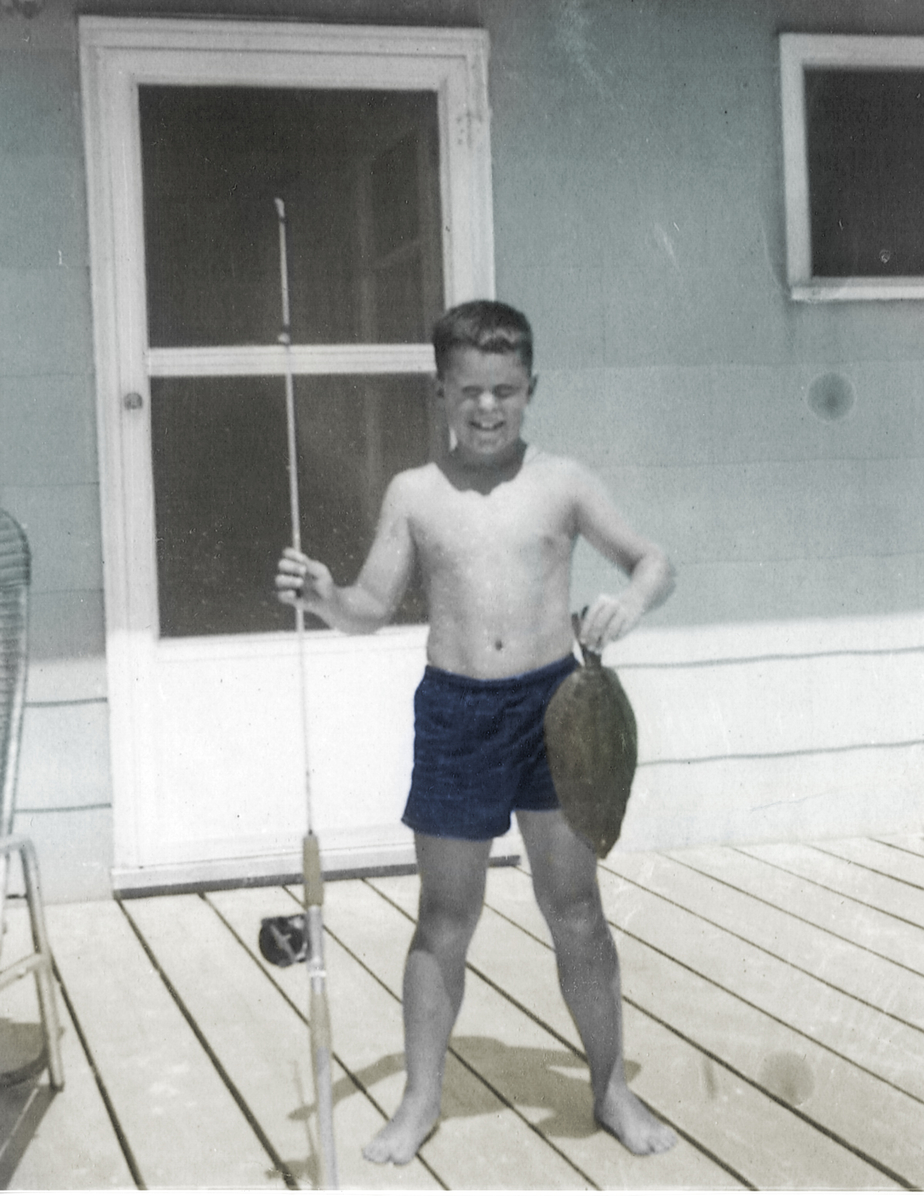

As a boy, the author’s favorite fish was flounder.

I smiled. Suddenly all of my frustrations caused by the traffic seemed to disappear. Memories of my boyhood summers spent with my grandparents at Saltaire, Fire Island, New York, began to come alive.

In all my years of wetting lines in various rivers, lakes and oceans across North America, I’d been skunked, stuck in the mud, seasick, rained on, frozen like an ice cube, sunburned, eaten alive by insects, parched and humiliated time and again. I had lost dozens of my favorite lures, but never could I remember ever having had a bad day fishing.

Once, when I was 12, I lost an entire casting rig on the pier at Saltaire. Using a heavy lead sinker and trying to make a long cast while bottom-fishing for flounders, I accidentally tossed my favorite saltwater rod and reel into a murky bay. I cried, mostly out of embarrassment, and my grandfather did what any good grandfather would do. He went out and got me a new rod and reel. As traumatic as that incident was, I don’t recall ever having viewed it as a bad day.

Another unforgettable event occurred in late August one summer. Once again, I was fishing off the Saltaire pier. Every year in late summer the snappers or baby bluefish would run in large schools in Great South Bay, which separates Fire Island from the mainland. At times, you could literally catch a fish on every cast. My grandfather had warned me several times about the perils of being a “fish hog.”

“Never take more than you can use,” he had warned me over and over again. Of course, I usually fished for flounders, and I seldom caught more than one fish on any given day. If I did get lucky and catch two flounders in the same day, that was like shooting a limit of grouse. It was a tough thing to do.

Fishing for flounders was hard work and there were many days when I never got a bite, which is why I never gave the fish-hog principle a second thought. Since I loved to eat flounder more than any other fish in the world, most of the fish I caught and took home literally went from the bucket into the frying pan. In addition to eating what I caught, I was expected to clean my catch as well. My grandfather taught me how to filet flounders as soon as I was old enough, and I promptly filleted any fish I brought home.

My big day of catching snappers started out like any other hot day in August. Using bait that my grandfather had helped me catch with a seining net, I was fishing with several of my best friends on the pier one sunny afternoon. Suddenly, the water started boiling as if a school of piranha were de-fleshing some poor animal like you might see in a Tarzan movie. All at once, we started reeling in eight- to 10-inch snappers every time we threw the line out.

Before I knew it, my fish-carrying bucket was half-full. Then it was brimming over with flopping baby blues. I borrowed another bucket and started filling it up. Soon, I had three large buckets filled with snappers. In all, I probably had 70 or 80 fish. There were no limits back in those days, and I suppose I could have caught 500 snappers if I had kept on. But three buckets filled with snappers seemed to be enough, and I knew it would be a chore getting them home. I put one bucket in the basket of my bike and hung the other two over the handlebars.

My grandfather happened to be outside working when I pedaled up with my treasure. Like a conquering hero displaying the spoils of war, I was floating on clouds. I had just about convinced myself that I was the greatest fisherman on all of Fire Island when the look on his face told me that, just maybe, I could be wrong.

“You’ve got a big job ahead of you, cleaning all those fish,” he said. “You’d better get started right away because it’s almost dark.” He didn’t offer to help.

“You’ve got a big job ahead of you, cleaning all those fish,” he said. “You’d better get started right away because it’s almost dark.” He didn’t offer to help.

While my grandparents cooked and ate steaks, I cleaned those oily little snappers until my fingers were raw.

After dinner, Grandpa came outside and said, “I was going to cook a steak for you tonight, but I figured you’d rather eat bluefish instead. Looks like you’ll be eating snappers for a long time to come. Funny thing, though. I thought you said you didn’t like snappers that much.”

“I don’t,” I answered dryly. Then it hit me like a shark inhaling a minnow. Suddenly the greatest fisherman on Fire Island was nothing more than a lowly “fish hog” who had caught way too many snappers.

My grandfather never said a word about catching more fish than I could ever hope to eat. He didn’t have to. I knew what I had done, and I knew what was expected of me. I ate bluefish for the next two weeks. Feeling sorry for me, my grandmother prepared them every way possible. Finally, I could eat no more. The freezer was still half-full when I sheepishly approached my grandfather and asked him if I could bury what was left in grandmother’s garden.

“Blues never keep very well,” he said. “They should always be eaten fresh. Go ahead and put them in the garden.”

A long time passed before I could even look at a baby bluefish again, much less eat one. Despite the error of my ways, I never regarded that incident in any way as having been a negative experience or a bad day. Indeed, it taught me a good lesson.

My thoughts returned to the bumper sticker on the car in front of me. No, there’s no such thing as a bad day of fishing, I thought with a smile. In fact, now fully back to the reality of bumper-to-bumper traffic and living in a world where I had been separated from the beloved Fire Island of my youth for many decades, another wonderful thought suddenly popped into my head. If I could just relive that golden day in the sun for one moment and go back to that magical pier at Saltaire for one fleeting instant, I’d be willing to eat every one of those greasy little snappers right now, I told myself. I’d even eat them raw!

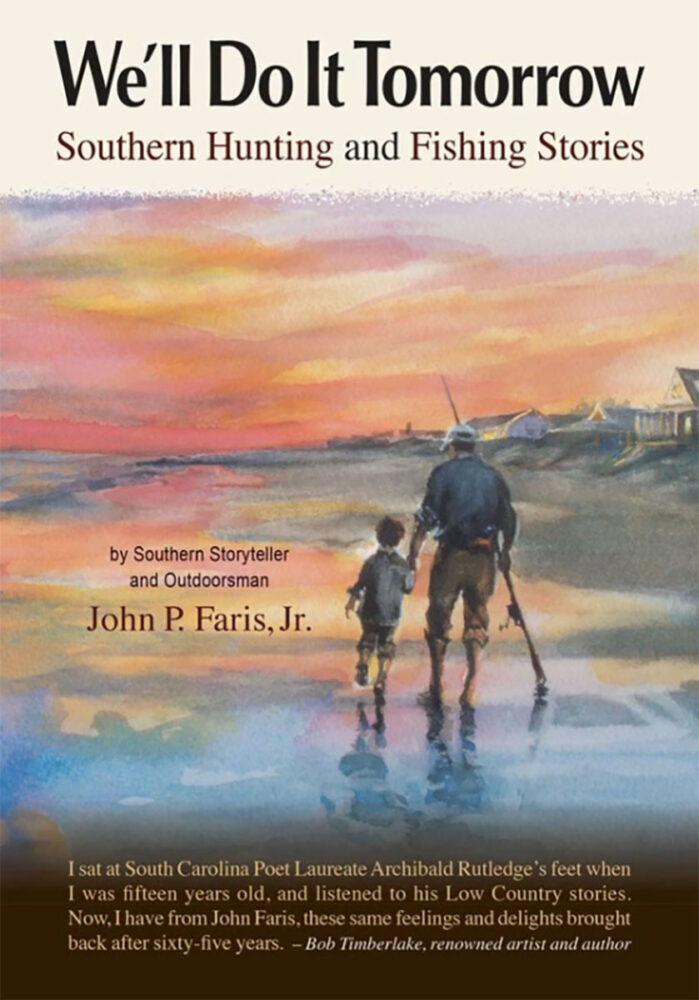

In this collection of stories, John takes us along the creeks and rivers of his native Laurens Country, South Carolina to shoot mallards and wood ducks. He also tells of unusual yet successful methods of taking white-tailed bucks on his farm in Union County, South Carolina. We’ll Do It Tomorrow is more than a book of tales about hunting and fishing, these stories are about the joys and sorrows of life. They will linger in your heart and leave you wishing for more. Filled with 15 stories and 30 illustrations We’ll Do It Tomorrow is definitely a keeper. Buy Now

In this collection of stories, John takes us along the creeks and rivers of his native Laurens Country, South Carolina to shoot mallards and wood ducks. He also tells of unusual yet successful methods of taking white-tailed bucks on his farm in Union County, South Carolina. We’ll Do It Tomorrow is more than a book of tales about hunting and fishing, these stories are about the joys and sorrows of life. They will linger in your heart and leave you wishing for more. Filled with 15 stories and 30 illustrations We’ll Do It Tomorrow is definitely a keeper. Buy Now