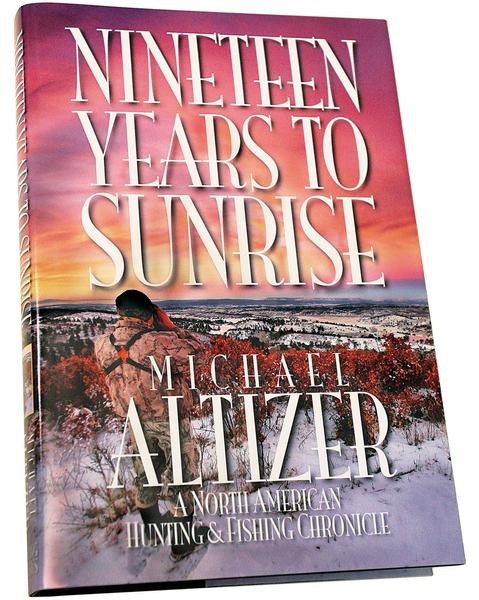

An excerpt from Altizer’s book Nineteen Years to Sunrise, available now from Sporting Classics.

We left the lodge the next morning an hour and a half before sunrise, heading back up into the high country. The night was sharp and clear and brutally cold. The sky was studded with stars, and our senses and souls were vital and alive and brimming with hope.

It promised to be a perfect morning for photographs, so at the last minute my good friend and editor of Sporting Classics Chuck Wechsler decided to joins us with his camera. At first light we spotted them—a small group of bulls far to the southwest above Iron Springs Lake.

We immediately began our move, dropping into the canyon and then climbing out the other side before circling into the high valley below the herd. We spotted them again 300 yards above, all of them big but one truly outstanding, his mighty rack looking very much like the great bull from yesterday evening. For one fleeting moment I had him in my crosshairs, but the entire group began to suspect that something was amiss and started moving again.

We moved parallel with them from below, up the canyon through foot-deep snow. Again they paused and again I momentarily caught the big bull in my scope. But by now they seemed to sense that something was wrong and turned south along the ridge.

Jaime and I continued to move with them as we bore up the valley, but Chuck dropped down to be in position to cut them off should they double back.

We finally halted 250 yards below the spur where the ridgeline fell away. We could see them there above us in the low light of dawn as they milled about in the sparse cedar and scrub oak, first moving briefly north in the direction they had just come, then dropping away over the crest and disappearing altogether.

There was no possibility for us to head them off, so we tucked into the shadows, scanning the spur above and hoping they would circle back, me sitting with my rifle resting lightly on the shooting sticks as I covered the skyline while Jaime knelt close beside me glassing the ridge above.

Then from around the eastern flank came three big bulls, clearly on alert, peering back to the north. A moment later three or four more topped out 80 yards above them. I examined each as they came, searching for that one majestic herd bull we hoped was still with them.

The tall cedars and fragmented sprigs of oak brush that separated them seemed vast and empty.

And then there was movement.

At first it was just the tips of his antlers I saw, then his entire rack filling my scope as the morning parted and the great bull crested the ridge. He moved as I had always imagined he would, looming grand and elegant, slowly turning his head from side to side as he studied the scene, huge, bigger than any elk I had ever beheld.

The entire universe now existed only in my riflescope as I watched him. I knew this elk—I had known him for 19 years, confident that one day he would come, growing into my vision until he was complete.

And now he was complete, fluid in his every movement, royal in his demeanor, framed against the sky and the shaded ridge, turning slightly to the left as he began quartering downhill.

And on he came, step by step by resplendent step, his nose held forward into the swirling wind, his great headdress flung back over his massive shoulders as he surveyed his last domain, turning fully broadside as I eased my rifle and myself off safety, the crosshairs probing his broad chest, searching for that lovely crease that I knew existed just behind his shoulder, distance certain, angle uphill, steady, breathe, don’t breathe, hold for him to clear, there, there . . . wait . . . wait . . .

The recoil was firm and controlled, and it lifted the muzzle of my rifle as I racked the bolt and reloaded. Pulling the scope back down, I saw him stumble and fall, then try to regain his feet, both of us knowing full well that he could not.

Immediately I sent another round flying up the mountain and into his chest to end it for him, and his noble head settled to earth as he surrendered to the Eternal. And still I watched him, my last round chambered, my finger on the trigger, his motionless shoulder covered by my crosshairs, I alert for any sign that might require this one final cartridge.

The air was icy and alive on my stubbled face, the rifle hot in my ungloved hands, the smooth, oil-finished walnut warm and reassuring as it pressed firmly into my face. The silence was palpable and nearly overwhelming as the muffled echoes of my shots coursed the canyon walls and came circling back into the focused reality that for the past few moments had been centered in my scope, and from some far realm I could hear Jaime’s distant voice.

I lifted my head and peered over the top of the rifle at our elk, then turned to Jaime, still kneeling close beside me, and he smiled his grandest smile and flung his arm around my shoulders and shook me, and I was back from the killing.

Two of Michael Altizer’s books, Nineteen Years to Sunrise and The Last Best Day, are available from Sporting Classics. He is also the magazine’s Ramblings columnist and a frequent feature writer; be sure to subscribe today to get his and other great articles delivered directly to your door eight times a year!