It is important for a man to do a thing well, even if it is killing. The honor of a feat is the measure of how you do it…And what was the truth of me?

To hell with Bob Ruark. To blazes with Hemingway, Capstick, Percival, Boddington, the whole and bunch of them. It’s enough that I struggle with the demons of my own conscience, at a thing at which I have been reasonably successful for the better part of my years. The more damnable that I must be over-burdened by their cumulative misgivings as well. By all they have said. So effectively they have built and amplified into diabolical aura, a presence which is outrightly flesh-and-blood, formidable without question, but blameless. Yet it is done, and impossible to ignore. Or to come to on my own.

It’s three o’clock on a muggy Tanzania morning, in a bush camp, and today I am to hunt buffalo, and it’s greatly their fault that I’m lying sleepless under canvas against a sweat-drenched pillow, uncertain whether the prickling of my skin is more the mosquitoes or the fear.

It’s three o’clock on a muggy Tanzania morning, in a bush camp, and today I am to hunt buffalo, and it’s greatly their fault that I’m lying sleepless under canvas against a sweat-drenched pillow, uncertain whether the prickling of my skin is more the mosquitoes or the fear.

While the damned irony is, it’s a thing I’ve pined most my life to do.

“The Lukula,” Sean Kelly, my PH, asked of the pilot, “how is it?”

The man, clad in khaki, gestures with the quaking flat of his hand. “Tricky,” he said of the primitive airstrip, “even if the ele’s haven’t trampled it.”

Minute-to-minute, Africa is built of intrigue. It accrues from the beginning.

We had chartered out of Dar, two hours airtime in a Cessna 206 for our tent camp on the Luwegu River in the depths of the Selous. An hour earlier I had sat in the lobby of the Colosseum Hotel, gear stacked alongside, sipping a colonial tea, mincing through Swahili from the local paper and relishing the unfolding unknown. Waiting for Sean to drop by, and the two of us to be off in what I fancied a safari-laden lorry. While others, obviously safari-bound too, waited there as well, weighing the suspense in the air or traded by, jabbering nervously. It wasn’t the Norfolk in Nairobi, and it wasn’t 1950, but it had felt like it, and it was East Africa.

We had chartered out of Dar, two hours airtime in a Cessna 206 for our tent camp on the Luwegu River in the depths of the Selous. An hour earlier I had sat in the lobby of the Colosseum Hotel, gear stacked alongside, sipping a colonial tea, mincing through Swahili from the local paper and relishing the unfolding unknown. Waiting for Sean to drop by, and the two of us to be off in what I fancied a safari-laden lorry. While others, obviously safari-bound too, waited there as well, weighing the suspense in the air or traded by, jabbering nervously. It wasn’t the Norfolk in Nairobi, and it wasn’t 1950, but it had felt like it, and it was East Africa.

“Hope you’re ready for the heat,” Sean said as we left. “It’ll be God-awful, bloody hot.”

Are you ever?

Nevertheless, the drone of the small plane had been life as I would have it, the ubiquitous tin-tops of the city melting away to the oblivion of the bush, 10,000 feet below, the push of the horizon stretching ever and on. It was hot and close in the cockpit, the small overhead vent a bare lifeline. But beneath, the wildness grew into great sandy river corridors, sucked almost dry by drought — hanging on by ribbons, by meager, withering lakes and lagoons. On their flanks, low miombo woodlands, dark, thick and deep. Intermittently loomed chalky sketches of spooky-white and skeletonized leadwood trees, abandoned by water over time, to die and be preserved for a human eternity. As here and there across the immensity of the landscape, a far-flung vista of rolling hills and high tawny plains, tall plumes of smoke lifted from smoldering fires. It was October, and it wanted to rain, but hadn’t yet.

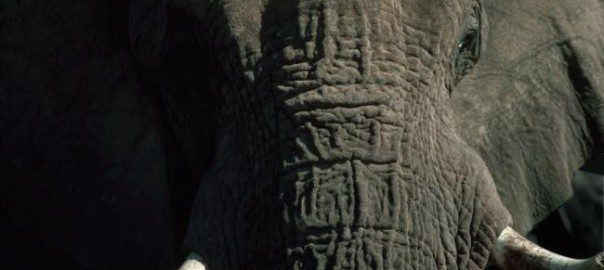

Magical, legendary, the Selous, spilling off the tongue with the same alluring intrigue as the Okavango, the Kalahari the Serengeti. The Se-loo — Old Africa, raw Africa, or nearest you can get. A remote, 50,000- square kilometers, the largest and wildest big game reserve in the world. Teeming herds of buffalo. Lion. Hippo. Leopard. Africa’s last, great stronghold of elephant.

Remnants of the same ivory that brought Frederick Courtenay Selous to legend in the last of the 19th century, and ultimately to his death in its defense, in the 20th — below Sugar Mountain, at Beho Beho, by the Rafiji. So respected was the English hunter/explorer and author that his demise by German sniper fire was lamented as “ungentlemanly” by enemy Commandant Loettow von Vorbeck.

“One day I will be a hunter in Africa,” Selous had said as a student to his headmaster at Rugby, who found him sleeping on a cold floor in his nightshirt. “I’m hardening myself to sleep on the ground.” He had kept the promise, to be acknowledged greatest of them all.

“The man not even the elephants could kill,” claimed the Matebele tribal chiefs.

In 1922, the Selous was named for him, and he is buried here, originally under a simple wooden cross, beneath a tamarind tree, in an inhospitable region loved by lion, hippo, elephant and rhino. A fit ending for a man so untamed.

“All that history,” I remarked to Sean. He grinned.

“We’ll make our own,” he said.

“I’ll get you so close you can smell his aasshh,” Sean had promised, when first we had spoken of this hunt. He was good to his word.

It was only mid-morning of the first day, and for the last hour we had been slip-sliding along through stifling-thick bush, playing the wind, within 30 yards of the herd. Trying to get ahead of them, trying to sort out the bulls. Having a hard time doing it. The old, hard bulls were at the front, contrary to their classic pattern. We had tracked them since bare day, the spoor strengthening. Until Allan, our tracker, had stuck a finger in fresh, loose dung and I in turn, and it came back warm and pungent.

It was only mid-morning of the first day, and for the last hour we had been slip-sliding along through stifling-thick bush, playing the wind, within 30 yards of the herd. Trying to get ahead of them, trying to sort out the bulls. Having a hard time doing it. The old, hard bulls were at the front, contrary to their classic pattern. We had tracked them since bare day, the spoor strengthening. Until Allan, our tracker, had stuck a finger in fresh, loose dung and I in turn, and it came back warm and pungent.

Once, Sean had stopped abruptly, listening painfully. Then had shook his head. “A rumbling, I thought,” he whispered. He listened a moment longer before we stole on.

A minute later we blundered into a feeding elephant, almost impossible to detect in the thick, matted brush. We almost didn’t. Only Sean, at the last moment, before the agitated bull whirled and flared, and Allan, 10 yards close, hurried past me to the rear, eyes wide with alarm. We had quickly backed away, facing the threat, rifles up and ready. I could see only gray, towering pieces of his hide. Fortunately, he did not press the issue.

Now, we had slammed stop again. Suddenly, Sean had snapped his fingers, and immediately we had frozen, sinking slowly to our knees.

Around us, whisper close, the unsuspecting herd was about its foraging ritual, drifting gradually along a koronga. In the thick cover, the whole of them was huge and daunting; even the cows were black and menacing. You could hear the low rumble of their stomachs, the gruff grunts and stiff harruummphs of their jostling as they shoved one another aside. The unsettling bleat of a calf.

Twenty yards ahead stood a bull, maybe 38 or 39 inches in the horn, better than average for the Selous. Massive and thick, sable and sinister. He was bullying the brush with his helmet. I could smell his ass, the thick, permeating stench of the runny green dung that plastered his buttocks. It condensed on the anxiety-laden air like warm dew on a cool blade of grass. I was worrying what would happen when he found us.

I shifted slightly. The bull raised his head, searching. Sean lowered his binoculars, raised a finger to his lips, cautioning me. Here was the perfect situation, and I knew it. I was getting ready, fighting my nerves, expecting Sean to order the moment of truth.

My heart was pounding, and I was working to talk it down. The heat was steamy and cruel. The soldier ants were under my gaiters again, the burning sting of their bites a needling aggravation at my ankles. Sweat poured down my face, welling in smarting eyes and my legs were cramped and searing from sitting on my haunches for long, merciless minutes.

Reassuring myself with the presence of the big double rifle, my thumb waited on the safety. The shrill, single note of some strange bird rose three times, punctuating the suspense.

Before I had left home, I had pledged to a friend, who has hunted Africa and knew I was going, “that should I get back, I’d give him the account.” And he had said casually to me “Oh, you’ll be back — a lot would have to go wrong for it to happen … to get killed by a buffalo.”

It didn’t feel like a lot would have to happen. It felt like damn little would have to happen.

“Good,” Sean whispered finally, “bloody nice sweep and kick-backs. But soft, still.”

I shouldn’t have been relieved as we backed away, but I was.

We made a couple more loops to the front of the herd, with nothing more promising, then left them on their way to bed.

Later, we came upon a hippo, grumpy, pompous old bastard on a grassy plain, a surprisingly long way from water.

“Damn surly brute, the hippo,” Sean had said. “Bump them on dry land and they’ll as likely come. Rarely mock charge on land.”

Midst the bravery of a buffalo hunt, I thought, it would not be elegant to be trampled by a hippo.

“I’d rather not like to shoot one,” Sean said, skirting the possibility. Already that year, there had been two.

This one we could avoid, didn’t have to shoot. There would be others.

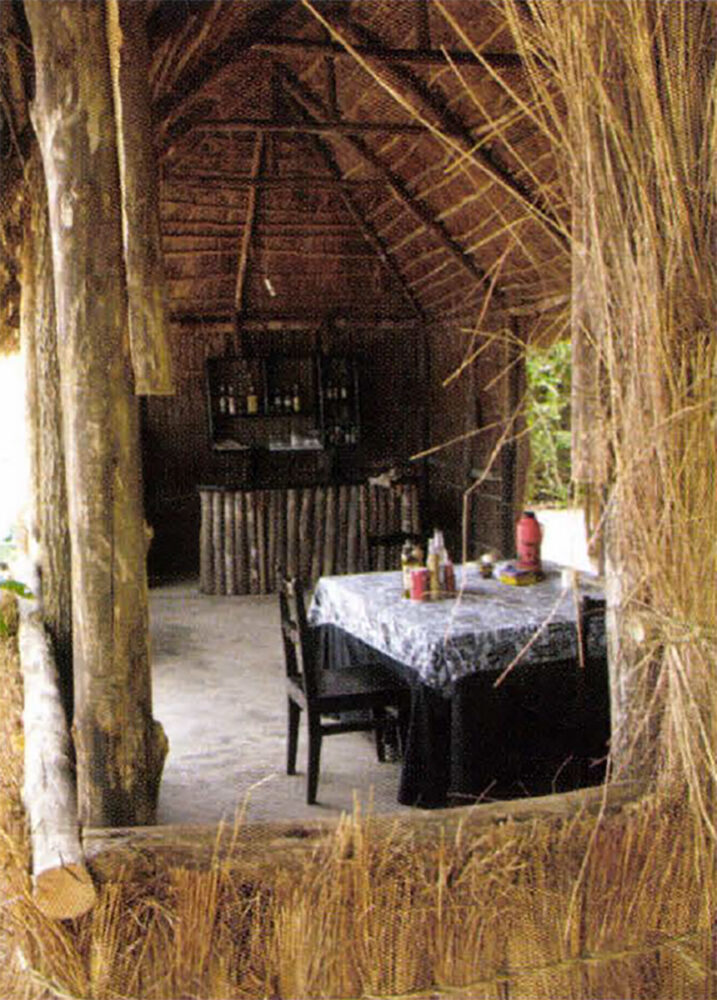

Lunch done, I’m mellow, and Africa’s all around; Andrea had tall glasses of chilled apple juice waiting when we pulled in — “Jambo, Bwana” — could you ever tire of it? Pork chops, corn-on-the-cob, a pasta salad, some chopped squash, a grilled cheese sandwich, filled us out about right.

Now, we’re on our backs napping, or trying too. Until we meet again at three, to make a plan. Camp’s hard on the riverbank, and my tent’s shaded and wonderfully livable, but it’s still hot as a whore in a Quonset hut, the air temp pushing 45 degree C. The humidity so thick you could cut and stack it.

So I’m watching the bull elephant on the sandbar across the way, ponderously thrashing the water, periodically lifting his trunk to shower himself. The small bands of waterbuck, that will become a daily pattern, walking and grazing the river’s edge. The yellow-green crocs sleeping semi-dead against the gray-blue of the water under the caress of the sun.

Afternoons will become a matter of chance . . . of getting lucky. It’s too late to take up a track, but maybe we’ll catch the buffalo coming to water. Mostly not, but the reccies I will come to anticipate, as they will be filled with adventure, nonetheless.

That first afternoon — cruising and hoping – was without buffalo, much as the others would be. But elephant are everywhere. Yellow baboon. Wildebeest. Impala. Bushbuck. A tribe of warthog. Charcoal bunches of waterbok. A multi-colored aviary of song and water birds.

I am close to pulling the big double from its case only once. The makeshift trail we follow narrows to a mere gap between the bush. The car slows. It happens in the twitch of an instant. Out of the thickets — point blank — barrels an elephant, a half-grown bull, eyes narrowed to small black coals, ears flared, trunk raised, trumpeting. He is bent on coming through us all.

“Haaa!” Sean yells once, “HAAA!” Twice. He’s still coming.

My hand grabs the waist of the stock, my fingers around two thick cartridges in my vest. At last, the angry bull slams to a halt, a few feet away, the fine, choking dust boiling and wrapping around us. He shakes his head, starts back, turns again. “HAAA!”

Reluctantly he retreats, leaving me quaking.

My God, I’m thinking. Even the teenagers.

Trailing out of the river bottom, dusk is sweet with the breath of monkey-apple. It reminded me of jasmine, cloying the evening air around a southern country homeplace back in the States.

“There’s our problem,” Sean said, pointing to the full moon. “They’re layin’ up, the buffalo, these hot days. Waiting for the cool of the dark. Just not getting to the river in time.”

Distantly in the twilight rose the fanatic chuckle of a hyena. The wallowing crash of a hippo from the river. The car lurched, as Nbliasi jerked it free of a honey-bear hole. Night was falling. Camp and dinner was a pleasant, swelling under-thought.

“Well,” Sean said, “it’s been a hell of an opener. You almost walked up the asshole of an elephant, were in the stinkin’ midst of buffalo and got mock-charged by a juvenile tembo.”

We looked at each other and grinned.

“A grand hell of an opener,” I agreed.

“Use enough gun,” the Man had said. I’d taken him to heart. Forewarned is forearmed. So I carried almost the longest, and certainly the best, in the world. A back-actioned, Holland & Holland Round-Bodied Sidelock, in 3-inch, .500 Nitro Express, regulated for traditional 570-grain Kynochs. A beautiful, fearsome thing, and the only way I had ever wanted to shoot a buffalo. The only way I would allow myself to hunt them. Close-on, With a Holland double.

“Use enough gun,” the Man had said. I’d taken him to heart. Forewarned is forearmed. So I carried almost the longest, and certainly the best, in the world. A back-actioned, Holland & Holland Round-Bodied Sidelock, in 3-inch, .500 Nitro Express, regulated for traditional 570-grain Kynochs. A beautiful, fearsome thing, and the only way I had ever wanted to shoot a buffalo. The only way I would allow myself to hunt them. Close-on, With a Holland double.

Any big double from a premier maker is an incomparable mix of grace, beauty and awe. The awe comes from a heavy caliber like the .500, the beauty from bespoken, Old World quality craftsmanship. But the grace — the “coming-in” of a fine double — is a delicate and almost indescribable matter of form and feeling, parlayed from something apart. A mince of history, happening, legend and longing. No one does “grace” better than Holland.

With every clunk of heavy cartridges into huge hollow chambers, each a cavern of eternity, grows another welcome reassurance.

But sooner than later, you must take again, your pillow. Try to sleep. Now again, I’m alone with myself. It’s the black edge of morning, the night sweats are back, and the demons are at me again. After the dark, piercing honesty of the buffalo bull, point-on this morning, I am riddled once more with uncertainty. It’s a far different thing to know the only fear between you and the creature you have pitted yourself against is your own. Bravery wears easily until it is called to test.

Ruark might have told the whole of it. You’re prodding a fight you better be able to finish. The beast you are badgering didn’t invite you here. It’s more than the glare of owing him money. It’s more closely that you’ve loaned the mortgage on your life, and that he is fully willing and able to foreclose.

In the end, it is a given. The courage and strength of the buffalo will not abandon him. Of yourself: the surety is less certain. You have to kill him. Or if he is to live, be of truth to himself, he must kill you. Die in the trying.

It is important for a man to do a thing well, even if it is killing. The honor of a feat is the measure of how you do it. If it comes to it, it is better for a man to die in body than in his mind.

Men search for comparables. There is no comparable to a buffalo.

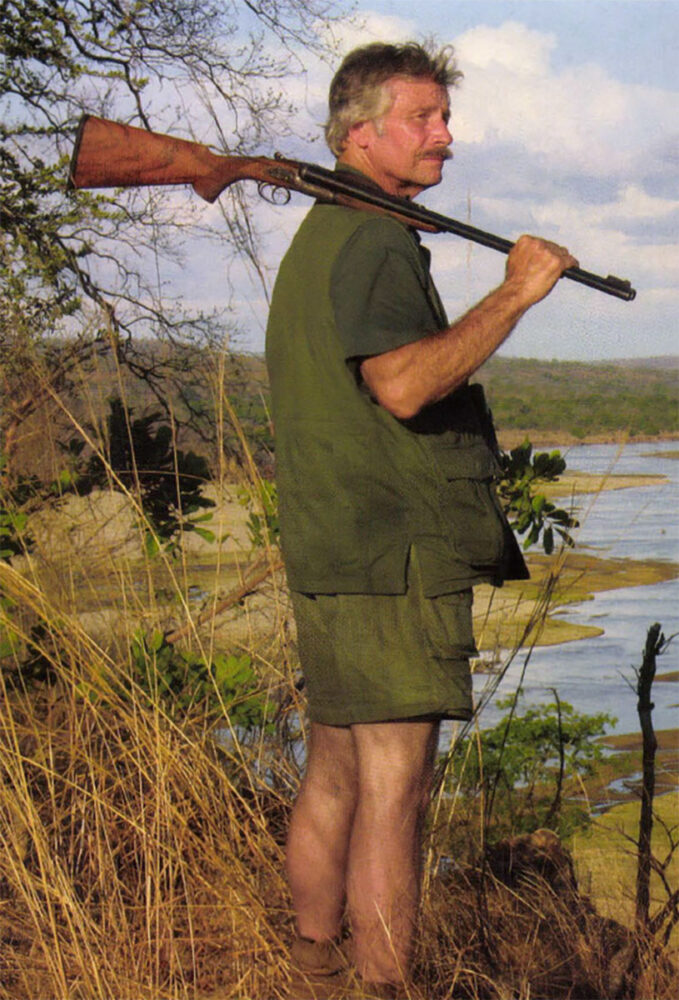

Sean and I have hunted together twice before. The morning of the second day, before we were off, he picked up the big Holland. “I didn’t know who I was happier to see,” he said, “you or this rifle.”

“Dance with the one you’re with,” I said.

He laughed. Sean’s a stalwart young man of unusual good humor, utterly dependable, of a good South African family who values honor. He had his unscoped Dakota .458, a gun that already could tell many tales. I knew of no one I’d rather have backing me.

I ask him if the notches in his ears registered the number of hippos he’s had to dispatch. He winced. “The bloody sun,” he says, “has teeth.” I pull on my hat. Africa is a land of many perils.

The sun was still sleeping when we cut the first track. Twice we had to circle, the spoor confused in a tangle of elephant tracks. But Samuel and Allan work it through. By eight o’clock, we were with the herd, playing the same game as before. Loop-de-loop, to gain the front. To get ahead of the bulls. On our haunches, at 25 yards, trying to see what was there. In cover so thick it was almost suffocating. Exciting stuff.

The sun was still sleeping when we cut the first track. Twice we had to circle, the spoor confused in a tangle of elephant tracks. But Samuel and Allan work it through. By eight o’clock, we were with the herd, playing the same game as before. Loop-de-loop, to gain the front. To get ahead of the bulls. On our haunches, at 25 yards, trying to see what was there. In cover so thick it was almost suffocating. Exciting stuff.

You could smell them, feel them. Taste them, almost, if my mouth hadn’t been so dry from the nerves. Of not only the ploy with the buffalo, but the incessant vigil for hippo. You could never let down, not for a moment. But it was a fool’s game, with the herd. They were moving too fast. We couldn’t get ahead of them in the dense cover; kept seeing the same animals. Finally, after two-and-a-half hours slap-middle of them, they slowed, and we were able to almost manage the fore.

There were the mature bulls. One hard old warrior, though only about 34 inches. He glared. It was if he had the measure of me in the split of a second, knew the truth of me more thane ven I ever had, and I could not stop the twitch of my stomach. The rest plodded on; we couldn’t really make them out.

We backed away, out of the bush, over parched and cracked grassland spocked deeply by the travel of elephant and hippo. The going to higher ground was treacherous. There we waited for the car.

“Bahati,” Sean exclaimed, shaking his head. “You see how it is, Myke, working the herds this way, in this thick cover? Bahati. Pure luck. Pure blind, Aussie luck.

“It robs us of our skill. We can’t move fast enough to get ahead of them. Pure luck, stumbling onto a good, mature bull. We did everything perfectly, but they were moving too fast. We need a group of old bulls, where we can use our skills.”

He looked away, then back.

“Kali, the old ones,” he said. “Very sharp, very wary. They will face the danger, not run from it.

“Kali,” he said again, “but we can beat them.

“Maybe we’ll find us an ancient, old scrim-cap,” he said.

I have seen them before, the old and hard and mud-caked sons-of-Satan with the worn or splintered horns, that are past herd sovereignty. That must fend as a few, or on their own. Gnarly, proud, eccentric and ill. They give you shivers.

We crossed the first spoor of lion that afternoon. And leopard. A huge male, by the stride, over seven feet. “My favorite hunt,” Sean says, “the cats.”

“And why?” I said.

“More of the mind,” he declared.

We passed the monolithic, ragged tower of stone that housed the craggy face of the Man-In-The-Rock. On our way to Lookout Hill. Past Little Tabletop Mountain. A bellwether of the hunt, The Old Man, Sean had ventured. To me, he seemed stoic as ever. Again, there were no buffalo. Again, the big gun did not clear its case.

But we were not so desperate as the Botswana party Sean told me of, which found itself eight days into safari void of even a fresh track. The client, worn and disgusted, peevishly directed the PH to ask of his Bushman tracker, “Where are all your buffalo?” Which the PH dutifully translated, and the little man — a river Bushman, not a San — thought for a time, said “Tell your client, if he’s asking where my cattle are, I can tell him of each and every one. If he wants to know where God’s cattle are, he must ask Him.”

But we were not so desperate as the Botswana party Sean told me of, which found itself eight days into safari void of even a fresh track. The client, worn and disgusted, peevishly directed the PH to ask of his Bushman tracker, “Where are all your buffalo?” Which the PH dutifully translated, and the little man — a river Bushman, not a San — thought for a time, said “Tell your client, if he’s asking where my cattle are, I can tell him of each and every one. If he wants to know where God’s cattle are, he must ask Him.”

Another evening had run lean, but the morning had been good, quiver-tight against another herd. We’d spotted a kudu bull, about a mile away, under a mahogany tree. A pack of wild dogs resting from their evening’s hunt, on a grassy green island.

On the way home now, we saw in the dust the spoor of lion again, and bushpig, and little, wandering ticky-tacky trails where the francolin had walked. At every dampening rose swirling storms of butterflies, lemon and lime. Behind us, the sun was dying over the river, bleeding molten orange onto glimmering water. Waterbuck fed peacefully along ocher sandbars. Elephant loitered, great and gray, on shadowy-yellow shores.

Dusk was closing, as we stopped thecar, gazed back over it all one last time.

“Another shitty day in Africa,” Sean said.

And what was the truth of me, I wondered? Night was back, and the heat and the sweat. The long, dark, piercing and sleepless hours between midnight and bare dawn. I asked myself, again, why this is so much a thing I must do? Kill a buffalo. I could be lying safely home in bed, against the warmth of my wife, 8000 miles west of this place.

On one plain I know exactly why I am here. On another, it’s ambiguous, strangely threaded to the remorse of my first boyhood squirrel. Stemming back to the burden of taking a life. At some point of honesty, I tell myself, in a lifetime of hunting, it has become a moral necessity that I risk my own. If I will ask him to die, I must be ready to do the same.

But there’s more, and I know it. The mettle of a man can be tested only at the pinnacle of his fear. There are two reasons a man comes to the moment of killing a lion, a buffalo, an elephant or a grizzly. The first is that he would gain the respect of other men his kind. The greater is that he would augur his own. What he can take away of himself.

It is not just the fear, but the doubt, its constant companion. It drives a man to cipher the sum of his life and living, and the older he gets the more desperate he becomes. To find a truthful measure. Ultimately, it is the fate of every civilized man to know with himself that he can pretend bravery, and most likely, never have it truly called to test.

Between a man and a buffalo, there is no pretense.

Each day we have come a bit closer. Today is the day I am to know.

On our bellies, in the sweltering red sand, Sean, Samuel, Allan and I had gauged at length a very good bull yesterday. Thirty-seven inches probably, beautifully configured. Heavy bosses, graceful flip-backs. In sparse forest this time, making it hard to close. We were 60 yards far, for a double andiron sights. Doable, but dicey. He had angrily tossed his head, turned away twice. If I hurt him, he would not again. At a point, I was almost sure we would try to take him, and it was harder than I wished to push aside the fear.

We had passed, finally, hoping for bigger but I could not deny with myself that with the relief came also another quiver of doubt.

This morning, only a short time before, we had encountered the lions. Not the old man, skulking successfully, but his lionesses. Lying in the yellow grass, their eager ears and burning eyes only vaguely perceptible. They had left me thinking, that on the ground should they want, they could easily take you unaware, come like splintered lightning.

My mind was still uneasy as we made our way to a promising buffalo woods below the soaring river cliff called Lookout Hill. We never got there.

“Mbogo.” Samuel. The mere breath of the word and the air stiffens. The polarity of the hunt swings dead sober. Foreboding travels your body like electricity through a hot wire.

They are more than a kilo away, five bulls standing distantly on the yellow slope of a swelling hill. Sean and Samuel are off the car, binos at work, waging their measure. I raise my own glasses, and my heart throttles. Even from here, they are bloody massive.

Sean motions me down. “Get your rifle.” My stomach turns queasy. Allan hands him his own.

There is a broad koronga, another ridge, between us and the buffalo. The herd is in view now, scattered along the long hill, above the bulls.

“One of them is very good,” Sean says, as Samuel steals quietly off down the deep slope into the koronga, Sean tight behind him, me glued to Sean.

“We must be very careful,” Sean has warned, “there’s a herd of elephants ahead of us. We’ve got to get around them. House them and it’s over.”

In my palm the heavy Holland has never felt better. Two big softs chambered home. But it’s Ruark again, Capstick … and my heart’s pounding like the south stroke of a sledgehammer. I knew it at my soul this time. All the midnight desperation was about to come down to a few piercing seconds of reckoning.

“Divide him into thirds no matter how he’s standing,” Sean has said. “Shoot low. His chest is deep. Take that two-pop and hammer him in the bottom third. Softs first, follow immediately with the solids. Just quartered straight on, clobber him point of the shoulder; if he turns to go, slam him up the rear. But whatever, keep the first one there and low.”

I was talking to myself; what must be done. Remembering the else, if it was not. “He was standing in his blood, waiting …” Samuel had said, of the badly shot Masailand bull that almost killed him. I needed to do this well.

Tedious minutes, avoiding the elephants, without the necessity of shooting one, but now we had made the slope of the intervening ridge. Then up and over it, to the gully beneath the bulls. The grass was taller and noisier than I expected. My shirt was soaked with nervous sweat, my eyes tearing from the salt, my ears thrumming with the heated rush of my blood. On we tipped, mincing our way, flinching at any tic.

Sean had chosen a big rock, on the hillside in line with the bulls, as a landmark. But now that we were closing, we could not find it. We were flying on gut instinct. Down now, crawling. Had to be close. One sparse bush to another.

On his knees, Sean cautiously lifted his eyes above the grass. Immediately, he dropped, turning his head under his near shoulder, mouthing to me and pointing.

“They’re bedded, just above us. Forty yards.”

I wiped the sweat off my hands, reseated them on the big double. Thumb on the safety. Ahead and just above was one small bush. We wiggled our way there. Only 25 yards now, to the near bull, the one we would challenge.

I have always nurtured respect for any wild thing I have dared. This time the more. But I was talking to myself again, cruelly, as I had never for so long as I have hunted. Hardening myself. There would be no quarter. I had Sean, I had the Holland and I had my wit. I, no one else, would die here. I would kill this black son-of-a-bitch and be done of the need.

Sean picked up a couple of small stones. “Up on your knees … get ready,” he mimed, “it’ll likely be straight on.”

I was on one knee, blood-hot, nervous and wet. But the big Holland came up and settled in. It weighed 10 pounds plus and the sights came in as faithfully as the Rock of Gibraltar. Just as Fate tossed us a crumb.

Down the hill lumbered a sixth bull, prodding the bedded five. In groans and grunts, all lurched immediately up, ready, stiffening for a fight. Six huge bulls, 20 yards off the muzzle. I don’t know that I felt anything at that point; impulse took the wheel. The greatest of them, the bull we would have, had jerked hard to his feet — broadside. Huge, threatening and black.

“Now!” Sean urged.

The grass was too damn high, his lower chest obscured. I traced his shoulder, held lower than I could see. Funniest thing, one of the awesomest calibers in the world, and I have no consciousness of recoil or report. The Holland popped and the thud of the first big bullet slammed him hard through the shoulders.

He hunched — whoomph — went down. In periphery, three of the other bulls whirled, glowering, face on. In my vaguest senses, Sean was up now too, with the Dakota.

The bloodied bull was fighting to get up, grunting, lurching along on his knees. I dodged sideways for a better angle. He wobbled, spun, facing away. Up the rear, something said. My finger found the second trigger. The big gun popped again, and the bull slumped, thudded again into the ground, dust boiling.

I jacked the spents, thumped in two solids. The other bulls, thank God, had retreated midst the furor.

My bull lay on his side, heaving, running red blood blackening onto the sand. Still he fought to face me, his spine smashed above his tail. His heavy horns slammed the ground, as again and again he threw his massive head, trying to rise. It was then that remorse fought through the steel shell of my resolve, and I began to become more of myself again.

“Between the shoulders,” Sean said. This time I felt the stiff thump of the rifle.

Suddenly it was over. Abruptly, it was done. Gradually swelled the dawning thought. I had done this thing, done it well.

I stood over the fallen buffalo. Already the ndege, the vultures, were arriving, wheeling the sky. In addition to the fresh tear of the bullets, the hull had an ugly, maggoty and horribly reeking gore wound in his neck. Should he have known we were there, he would have had reason to be surly and bad.

It was then that the trembles took hold. I ran hot and cold. Sweat poured. I tried to take pictures, and for the longest time, couldn’t.

Butchering a buffalo is largely a matter of parting him in halves, rolling the ends apart. Samuel cut free the great heart of him. It was most as big as my head. He held it aloft, the sacramental essence of a daunting foe, the fresh, thick blood pouring down his forearms.

“Mbogo,” he said in respect, once more for eternity.

A man lives 65 years, comes 8,000 miles, to find more than he has ever known that he is mortal. A buffalo calf is born, avoids the lions, survives 15 rains, grows old and gnarly, hard, wise and ill. Then, int he wish of a lifetime and the quick of a moment, destiny brings them together. One dies and one walks away. It is never certain which it will be. And whatever the conclusion, there looms the most mystifying question of all: When was their meeting decided? Yesterday, in the moment itself, or long, long ago?

A man lives 65 years, comes 8,000 miles, to find more than he has ever known that he is mortal. A buffalo calf is born, avoids the lions, survives 15 rains, grows old and gnarly, hard, wise and ill. Then, int he wish of a lifetime and the quick of a moment, destiny brings them together. One dies and one walks away. It is never certain which it will be. And whatever the conclusion, there looms the most mystifying question of all: When was their meeting decided? Yesterday, in the moment itself, or long, long ago?

Sean and I sat long by the campfire that last night by the Luwegu. We had spent the last three days of safari just wandering around Africa, warding off hippo, stopping with the boys for bush lunches of grilled buffalo loin by the water, walking across long grassy ridges under the scented, scarlet canopy of the mahogany trees. Hacking open the fruit of the baobab, and sucking it like tangerine. Looking across green hills to the horizons, knowing there are places here still, so inaccessible they have not been visited, likely, since the time of Selous. Wondering with a hunter’s heart — my Lord — what treasures of game must lurk there?

Over the river was a sheen of silver, born of the growing moon. Stars glinted like diamonds in a black-and-buttermilk sky. A lovely thing, it was, to ruminate before the flicker of the fire, safely past the dangers of the day. To absorb like a warm and soothing liniment, the touch and sights and sounds of a broad African night. Listening … feeling … waiting – all around, the African evening orchestra. Waxing … waning … until, finally, distantly, it comes … ughoommm, ughoommm … the hunting chant of the lions. A lovely thing, to think that yesterday you killed a buffalo, and a night ago you ate his heart — became one with him — and that tomorrow — the rest of your tomorrows — you could know a thing of yourself you could not before.

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now