As night fell, a dense bank of fog from the Indian Ocean pushed inland over the Mozambique coast, blocking the moonlight and cloaking the forest in darkness.

Condensation that had formed high in the jungle canopy literally rained down onto the leaf litter below. Just past the edge of the forest the expansive, treeless floodplains where buffalo and antelope fed during the day were still and silent under the weight of the heavy ocean air, and it seemed that across the entire coutada, or hunting area, nothing stirred.

As the men excitedly discussed their find, a huge male leopard appeared in the dim yellow glow of the headlights.

In Mark Haldane’s Zambeze Delta Safaris camp, the men had finished dinner, but rather than retiring to their tents, they began gathering their gear for a night of hunting deep within the forest.

Theunis Botha’s pack of hounds whined from within the truck, watching with great anticipation as Haldane and his team finished loading the vehicle before setting out from camp with the seemingly mad intent of pursuing leopards in the tangled shadows of Mozambique’s sand forests.

Mark Haldane is perhaps best known as a buffalo hunter, and his two concessions are home to tens of thousands of buffalo that graze over the wide plains and through miles of forested wilderness. His concessions also offer some of the world’s best hunting for animals such as sable, nyala and bushbuck. This abundance of plains game, coupled with the region’s lush vegetation, supports a large population of leopards, including many cats that attain immense proportions. But with such a large number of prey animals, the big cats rarely come to baits, making them even harder to hunt and increasing the odds that a tom will live long enough to reach maturity.

The lights of Haldane’s vehicle cut I through the fog as he rounded a curve on a sandy two-track that crossed his hunting area. On one side of the road, purple in the starlight, were the treeless plains. On the other side was the sand forest with its tangled and drooping creepers that clung to the great limbs of msasa and mahogany trees.

Haldane pressed on through die sand, stopping only when he saw a series of depressions in the wet earth. There, in the middle of the road, were the tracks of a big leopard. The rounded prints were wider than a man’s fist and not more than a few minutes old. With any luck they’d be able to set the dogs on the track and bay the cat before morning.

As the men excitedly discussed their find, a huge male leopard appeared in the dim yellow glow of the headlights. The tom turned to look at the hunting car, giving Haldane a brief moment to judge the leopard’s size before it bounded away into the forest. But that moment was all that Haldane needed.

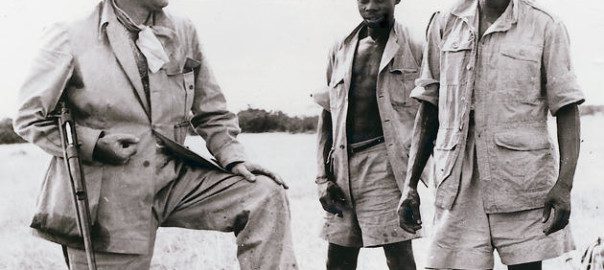

“That’s an excellent tom,” he said to his client Mark Verlander, and at Haldane’s command, Theunis and Witness, the native dog-handler, stepped out of the vehicle and pulled one of the strike hounds from the truck. The men watched the lanky bluetick race forward along the road, then spin around twice where the tom had been standing only seconds before.

The dog took deep breaths, blowing sand out beneath its muzzle as its long tail began wagging more quickly, then let out a long bawl and disappeared into the dark forest.

In the pea-soup fog, Haldane knew that all the moisture falling from the trees threatened to wash away the cat’s scent before the hounds could pick up its trail.

The mixed pack of blueticks, foxhounds and French Gascognes found the leopard’s trail, and soon they were in hot pursuit of the big cat. The men donned headlamps, loaded their rifles and shotguns, and set out into the ink-black forest, guided by the strident voices of the hounds.

It wasn’t long before the dogs brought the leopard to bay. Theunis told Haldane and Verlander that the cat had bayed on the ground and not in a tree as they had hoped. The drawn-out trailing cry of the hounds changed to a series of sharp, high-pitched barks as they surrounded the leopard, which was backed into a mass of dense creepers and low-growing limbs. As the men drew closer they heard the coughing roar of the cat and the frantic howling of the dogs as the tom lunged at his pursuers, slashing at them with outstretched claws.

“A leopard is smart enough to know that the dogs are just a nuisance, but approaching men are its real problem,’’ Haldane explained. “When the leopard sees you, it gets it. . . and it comes for you.’’

Approaching a leopard that has been bayed by hounds is dangerous in the daytime. Approaching a furious cat at night, guided only by the dim, orange glow of a headlamp, is akin to climbing blindfolded into, a Pamplonan bull ring.

Haldane instructed his client how to react if the leopard broke cover during a confrontation.

“You must turn off your light and put your back against a tree, immediately,’’ he said. “That way, the leopard may not see you and run past you before it realizes you’re there.’’

It was little comfort to Verlander, yet good advice for lessening the odds of being mauled or killed.

As the men approached the hounds and the leopard, Haldane heard the cat grunt and then rush from cover, scattering the terrified dogs. In the frenzied scramble, it was impossible to know which direction the leopard was running.

When the cat broke from the thicket, Haldane and Verlander shut down their lights and flattened themselves against the trunks of mahogany trees so they were facing each other about three feet apart.

Haldane felt something rush past him, almost touching his knee. It was a rippling black shadow, silent and terrifyingly quick. And in a moment the pack came boiling behind in hot pursuit of the leopard that had passed between Haldane and his client.

“He came right past me… I could have reached out and touched its back,’’ Haldane said of the encounter.

As the men regrouped, they strained to hear the already distant voices of the dogs racing at full cry after the leopard. As the men started out after the dogs, every rustling in the dark forest drew the orange glow of their headlamps, and every glistening leaf and pool of water looked like the round, white glow of an animal’s eye. The men continued on in the darkness, straining to close the distance between themselves and the pack.

The best circumstance would have been for the leopard to seek refuge in a tree, and on the next bay the cat selected just such an elevated position, though he wasn’t much higher than a man’s head. Rasping, hacking grunts from the leopard told the approaching men that the cat was just out of reach of the hounds, and as the men closed to within 20 yards, the cat leaped from its perch and rushed off into the blackness.

Once more the men stood flush against the trees, waiting for breathless seconds, but this time the leopard bolted away in the opposite direction. As the dogs took up the cat’s trail, the men turned on their lamps and began following the pack ever deeper into the forest.

The chase went on into the darkest hours of the night — the tireless hounds hot on the tom’s scent as he led them down hidden game trails until he bayed once again, then broke away in a furious rush that left every hunter pressed against the closest tree, knowing there would be no time to escape the terrible claws and fangs. It was a primordial fear, the sheer terror of meeting a deadly predator under cover of darkness, a sensation that our primitive ancestors must have felt when their fires died down, and the night became dark and still.

Despite the difficult tracking conditions and the dense vegetation, Theunis’ hounds never gave up, and the footsore men, their nerves rattled, continued to follow the coursing dogs all through the night. With headlamps scanning the forest floor for the eye-shine of cobras, the men tried — time and again — to approach the huge tom, hoping the cat would hold long enough for a shot. But each time it rushed away through the blackness with the clamoring pack in tow.

After a full night’s chase the leopard finally took refuge in a msasa tree, and for the first time since that fleeting moment six hours before the men saw the old tom in the flesh. By the faint, gray light of pre-dawn, Mark Verlander took a rest with his rifle and found the cat’s chest in his scope. There was a flash of light from the muzzle, and the leopard slumped down toward the moiling pack.

As first light came on, the tops of the trees were still shrouded in the sea fog, and the only sounds besides the dropping moisture were the panting of the weary pack and the morning calls of the forest birds. Then, as was tradition, Witness lifted a brass hunting horn and blew one long, somber note toward the coming dawn, the gathering call for lost members of the pack, and a song of celebration for their perilous pursuit in the wilds of Mozambique’s sand forest.

Sporting Classics has compiled this remarkable anthology showcasing the best African adventures published in our award-winning magazine.

Sporting Classics has compiled this remarkable anthology showcasing the best African adventures published in our award-winning magazine.

Ruark, Capstick, Roosevelt, Markham – the legends in outdoor literature are all here, sharing their stories of deadly encounters with dangerous game, of bizarre run-ins with witch doctors, gorillas and man-eaters, of safaris into the uncharted wilds of deepest Africa.

Illustrated by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Buy Now