Silence means danger in the black Amazon canopy as it swallows and suffocates you. The awful anticipation of what’s out there, watching and waiting, is exactly what keeps you from running and screaming, betraying your position and bringing down a swift, deadly consequence.

Each small sound that penetrates the jungle night puts you on edge, and the putrid odor of the rotting, three-day-old carcass mixed with the acrid sting of cat urine seems to permeate the humid air.

I try to get a better hold of the 12-gauge double, but the perspiration from my hands has soaked into the antique wood, certainly not adding to my courage or confidence in this poorly thought-out venture and venue.

Yet I wait. Will he come? The biggest part of me hopes No!, but what’s left of any good sense I have says Yes. The stress of these past few days is nearly too much to take, so I beg silently for an end to this one way or another. All the time my ears are straining in the sudden and silent darkness for that quiet whisper of soft padding feet . . . a twig snapping . . . some hint . . . some small gift from the gods . . . a warning . . . He is here!

Jose shook his head in disgusted recognition. Lying under the midday sun in a small clearing, partially eaten and half covered with debris, was the 19th head of beef killed by the jaguar in five months. The cause of death was evident even to me: a crushing bite to the cranium of the young steer that had been dragged to a secluded spot along this oil-green pond where the cat had hoped to dine undisturbed. And the kill would have gone undiscovered had not the sucha (vultures) given away his stash.

Jose examined the carcass closely. At least a day old, he pronounced. Clearing the brush away, he stepped back, looked at me and then back at the kill. The tracks of the assassin were huge!

Jose, who along with his dogs had hunted down many jaguars over the years, spoke in a hushed tone, as if hoping not to attract some unseen attention. “Un tiger muy grande!”

Less than an hour earlier Jose and I had been standing in the corral and kibitzing with Miguel, the estancia’s owner. We had been scouting out some areas for shooting wild pigeons and doves in preparation for some clients who were scheduled to arrive in a few days. Our conversation was interrupted by the clatter and dust of a horse coming at full gallop. Delphin, the head cowboy, raced into the yard shouting, “Tiger! Tiger!”

Pulling up hard and choking us with clouds of dust, he described with much drama and excited animation how and where he’d found the dead steer. He clearly believed the killer was a massive “tiger” (jaguars are called tigers by the locals and not tigre as you might think) and that it was still close by because he’s eaten only a small portion of the steer.

Jaguars are protected in most South American countries, though habitual cattle killers are routinely hunted down and destroyed. The region of Amazonia, including eastern Peru, northeastern Bolivia and western Brazil, is a sparsely populated countryside consisting mainly of ranching communities, most family owned and not at all lucrative. So any loss of stock is a serious matter.

Jose explained that a big tiger can virtually take over an estancia, feeding at will on cattle. Considering it their territory, and with beef being rather easy quarry, jaguars can and do put some of the poorer operations out of business. Worse yet, they often lose all fear of the gauchos. Though not widely recognized as true man-eaters, they certainly have a reputation in these regions as deadly killers!

This was certainly inconvenient timing with clients close to arriving; we really needed to be scouting birds, not solving Miguel’s feline problems. Yet he’d always been so gracious in hosting our groups of shooters, so I was reluctant to turn down his anguished request. It did seem like the best time to deal with the cat as all the signs were in our favor. As worried as I was about pursuing the cattle-killer, there was that 10-year-old boy inside me who was keenly excited about the adventure.

I had only been in Bolivia a few months, and somehow, by pluck or luck, I had found myself as a professional hunter, though so far I had not faced down anything more dangerous than an eared dove. I had hunted dangerous game in Africa, and truthfully, the big cats scared the be-jeesus out of me. Anything with such potential for savagery as a jaguar deserves as much respect as one can muster. Besides, I am no erstwhile Jim Corbett and this was no pretty kitty; this was 350 pounds of potential mayhem.

Jose was confident that if we got his best hounds on the cat’s trail right away, we could finish the hunt that afternoon. Resolving the issue quickly would keep us in Miguel’s favor and gain us future goodwill. And so, with a bit of trepidation, I agreed to join him.

By 2 p.m. we were back at the ranch, loading Jose’s Toyota pickup with six of his best dogs. I was thrilled to see Spartan, a 4-year-old male I had bred back in the Carolinas at Tryon Hunt Club. A registered American foxhound, he was my gift to Jose a year before, and I was very impressed that he’d made Jose’s first string of tiger dogs.

It takes a special canine to be a great tiger hound, as jaguars have a way of turning the tables so quickly, circling back on their own trail during the chase, then rushing out and killing the dogs one at a time, each with a single deadly blow. Along with Spartan, we had Chico, Carla, Pancho and two promising young bitches, Marisol and Valentine.

The hounds poured out into the cortina, working the moist air, noses down, tails up. It was Carla that struck first, bawling like a banshee, her voice like music to Jose and me. Soon the chase was on, with all of the hounds trailing the line, feathering off into the green tangle and singing full cry!

Jumping into the truck, we raced along a dirt track parallel to the pack. From the sound, they were not cold-trailing, but hot on the heels of the cat. Turning north, the cry became fainter so we drove fast as we could to the northern end of the ranch where we could make out the chaotic chop of bawls, barks and yelps. They had bayed the jaguar!

Jose grabbed his old 12 double and a pocket full of buckshot. We hit the ground at a run, tearing through brush and briars on our way to get to the dogs before the tiger had a chance to break or worse, before he killed some of the hounds. As we ran, the jungle vegetation grew thicker and I lost sight of Jose. With only the baying of the hounds to guide me, I splashed through a shallow stream, then up into a stand of grass taller than my head. When I broke through I was nearly on top of the swarming pack.

Pancho was lying on the ground off to my right. I could make out Chico, Spartan and the two young bitches, but Carla was nowhere to be seen.

My immediate concern was the jaguar. I could see where the dogs were baying, but for the life of me I couldn’t see the cat in the tall grass. And then it hit me: I had no gun! My only weapons were two leather dog leashes I’d been using to flog the brush in my haste to get to the hounds.

I realized I could be in serious trouble and started to back out when I inadvertently stepped on the paw of Spartan, who was holding his ground heroically. He let out a pained yelp, startling me and knocking me down in one quick move.

Waiting for its chance, the cat exploded from the grass in a flash of burnt yellow and black.

As I lay on the ground, I thought, My God! Is this how my life ends?

And then he was gone. I listened as the two pups disappeared across the river in hot pursuit.

Jose had been close by all the time, but couldn’t get up a steep bank to the hounds. As we stood there taking stock of things, the missing Carla showed up severely clawed. Pancho was also badly injured but after struggling to her feet, was able to walk. Jose leashed the hounds, but he carried little Carla all the way out of the swamp to the truck.

I inquired what might happen to Marisol and Valentine. Jose felt they would give up soon in the heat and come back or the tiger would kill them. I am happy to say that later that evening both girls showed up unhurt at the estancia.

By mid-afternoon the next day we were out scouting birds again; time was running short and we needed to locate some honey-holes. Glassing the miles of backroads on Miguel’s ranch, I could make out a vehicle racing in our direction, dust trailing. I started to get a sick feeling that this would not be good news. Miguel drove up, jumped from his pickup and told us to come quickly. One of his gauchos had encountered the tiger not far from yesterday’s kill. The cat had walked out of the cortina pretty as you please; Javier’s horse had reared wildly in panic, nearly dumping the frighten cowboy.

So what now? With two of the six dogs on the injured list, Jose was reluctant to put his remaining hounds on the track. He didn’t have enough dogs to take on a jaguar this clever and besides, most of them were largely inexperienced

“Well, Patron, there is another way,” Jose said.

“No! No! No!” I responded. “Not on your or my life! It’s too dark! That cat is too big! And too bold.”

Yes, Amigo, all of that is true . . . but his boldness will be his death.”

“Yeah, or mine!”

The “another way,” as it turned out, was to sit up at night close to the last kill. I would carry the 12 bore while Jose packed a big flashlight and a large hollow gourd that when scraped properly with a stick, sounds exactly like a growling jaguar defending his turf. So not only would we be sitting ducks in the dark, awaiting the arrival of six feet of spring steel muscle and savage claw, we would push the envelope further by introducing the element of territorial imperative!

Before taking on our certain suicide, I stopped at the hacienda to talk with Miguel, who asked if I’d like a drink before I heading out. He had been saving a bottle of 12-year-old scotch for a special occasion. I declined, deciding that I needed all my wits.

Several hours later I was seated on the forest floor, my back up against an ancient toborochi tree, bathed in perspiration as I watched the afternoon shadows grey into evening. Now was the time of the hunter, and I was alert to every sound: the patter of huge bird-spiders hunting through the mulch, the splash of a caiman in the river behind me, the awful screech of some night bird or hapless prey.

Jose was seated to my left against the same tree as we needed to stay close and keep our movement and noise to a minimum. We had worked out a system of taps to communicate the cat’s approach: one tap on my shoulder meant in front; two, he was on the right; and three, left. I would then turn the shotgun in the appropriate direction and at Jose’s final tap, he would turn on the flashlight and I’d fire the shotgun. Jose had gone over his plan several times, telling me what to expect. I hoped I had the nerve to pull it off.

As darkness settled in, Jose whispered, “Are you ready, Amigo?”

“Sure.” I checked the gun for the third time to make sure it was loaded. “Let’s see what happens.”

Until that moment, the blackness had been alive with all manner of activity, but as Jose scratched across the rough center of the gourd – Uuuunnggh! Uuuunnggh! – the night slipped into a nervous silence.

You could feel the presence of creatures around us – unseen, unheard. The sound they feared most in Amazonia, the deep-throated chuff of a jaguar on the hunt, had stilled the jungle night.

Again Jose: Uuuunnggh! Uuuunnggh!

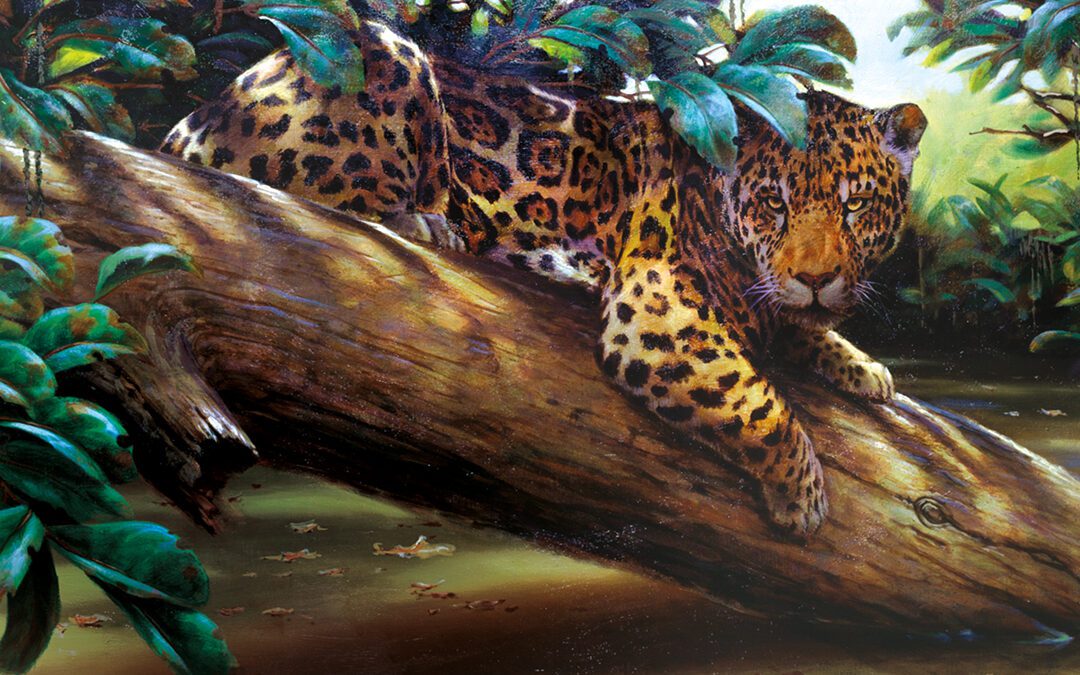

Jungle Cover Jaguar by Guy Coheleach

I nearly swallowed my tongue when the night was punctured with the guttural cough of the jaguar. We had our answer. I felt Jose’s hand on my shoulder. Was he was trying to calm me or himself? I didn’t dare move a muscle. I couldn’t blink. Hell, I can’t remember even breathing! The only thing I could feel was the stream of sweat pouring down my face, burning my eyes. No need to call again.

We could now make out a soft splashing as the tiger crossed the river behind us. This was not our plan. The well-used trail to the kill was in the completely opposite direction, so all of our plans were now up for grabs. To get to the carcass the jaguar would most likely pass within 10 to 15 feet of our tree, blocking any possible escape route away from the river.

I could see nothing, not even the rotting carcass, but I could hear (or did I imagine it?) the stealthy padding of huge paws coming closer and closer. My shirt was soaked with sweat, and I was aware of Jose’s tight grip on my shoulder. Perhaps he thought I might run?

Several more seconds passed and I still couldn’t see the cat, though now I could hear him breathing and even smell his distinct feline odor. There are few experiences on earth that will give you that low-voltage, stomach-dropping shock, like finding yourself within a few feet of a deadly predator. It was a strange sensation of intense fear and exhilaration.

Jose tapped once, paused, then tapped again. The night burst into view as he clicked on the torch. Eyes of fire and shock stared at us from less than four gun-lengths away! For one brief second I was frozen. I cannot remember raising the gun or if I had already done so, or whether I fired both barrels simultaneously or back to back.

I saw the huge cat jump off to the right into the jungle, Jose keeping his light on the brush where the cat had disappeared. I recovered quickly, reloaded and swung on the spot. We waited for what was an eternity, as if neither one of us wanted to be the first to claim some victory.

Finally, I could make out the distant hum of a vehicle, and minutes later came the shouts of Miguel and Delphin. Having heard the gunfire, they had come to check on us, hopeful of good news.

Regaining our composure, Jose and I edged up the bank to where the cat had been standing. Only 12 paces! We pushed on carefully, Jose scanning every blade of grass and twig. Then he appeared: a beautiful amber and obsidian carpet on a bed of velvet moss. The only imperfections were the massive holes that perforated his hide from head to throat and the smear of gore draining onto the ground.

Kneeling, I was finally able to put my hands on the object of my fear and nightmares. In a strange, sad way I could sense a certain dignity and savage grace that even death couldn’t steal away.

I was weak and a little sick. I knew the cat had to be killed, but I felt that a big part of the jungle I’d come to love, what the Amazon was all about, had died a little with him. Jose, I know, felt it too, and together we shared a few silent moments of responsibility for what we’d done.

“Es un trabajo muy triste, mi amigo.” (It is sad work, my friend.)

But you can be sure I was grateful that it had turned out as it did. As Miguel and his gaucho approached, shouting cheers and thanks, I could see that he’d brought the bottle of scotch with him. Now, I don’t mind if I do.He poured Jose and me a long one, as the cacophony of the Amazonia night slowly returned, just as it should be!