It might surprise you to know that NFL legend Bert Jones and his father Dub are hard-core quail hunters and bird dog men.

Joe Augustine, who happens to be a friend of mine, is one of the handful of sportsmen who’s bagged every species of upland gamebird in North America over his dogs—English setters, in Joe’s case. It also happens that Joe and his dogs, four at last count, live in Manhattan. This is not where you expect a dead-serious bird hunter and his dogs to live, but Joe makes it work.

In any event, one winter Joe was walking his setters on Park Avenue (!) when he was buttonholed by a stranger who wanted to know about them. The guy, who had chiseled features and looked to be in his 50s, was rangy and obviously very fit, and while something about him seemed familiar, Joe couldn’t quite place him. He spoke in a soft Southern drawl, and over the course of a conversation that stretched to nearly a half hour the guy told Joe that he had a kennelful of bird dogs, setters and pointers both, back home in Louisiana; that he was in the lumber business there; and that he had a quail lease in West Texas where he turned his dogs loose as often as he could.

He also mentioned that he trains them himself, and in contrast to the usual Texas MO of hunting from a tricked-out pickup or ATV (in Texas they call these rigs “quail buggies”), he does his bird hunting from the saddle of a walking horse.

The guy hadn’t mentioned his name, but the longer he talked, the more certain Joe was that he knew him from somewhere. Suddenly the light came on.

“Are you Bert Jones?” Joe asked.

“Yeah,” he answered, “I am.”

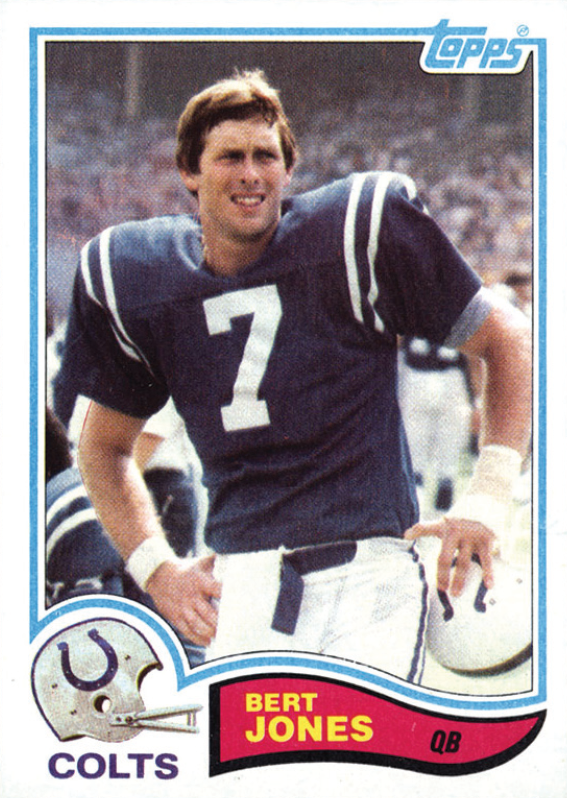

Bert Jones! Consensus All-American quarterback at LSU, second overall pick by the Baltimore Colts in the 1973 NFL draft, the league’s MVP in 1976 and one of the purest passers in the history of the game. There wasn’t a throw he couldn’t make; those of us of a certain age can still see him in our mind’s eye, Number 7 in Baltimore blue, standing tall in the pocket and delivering one perfect spiral after another to his receivers.

A touch pass in the flat to Lydell Mitchell. A bomb deep downfield to Roger Carr. A bullet to Raymond Chester across the middle.

Bert Jones’ accomplishments are a matter of record, but here’s a factoid that really jumps out. During the decade of the 1970s, only three NFL quarterbacks eclipsed 100, the magical passer-rating benchmark, for an entire season: Roger Staubach, Kenny Stabler and Bert Jones.

Bert Jones’ accomplishments are a matter of record, but here’s a factoid that really jumps out. During the decade of the 1970s, only three NFL quarterbacks eclipsed 100, the magical passer-rating benchmark, for an entire season: Roger Staubach, Kenny Stabler and Bert Jones.

The guy could play.

And if you’re thinking that the numbers aren’t adding up here, Jones only looks 50ish. In point of fact, he’s 65. I know this because shortly after their chance encounter on the mean streets of Manhattan, Joe called to tell me about it, rightly assuming that I’d not only remember Bert Jones but that I’d find it cool as hell that this NFL legend is a hard-core quail hunter and bird dog man.

“He couldn’t be a nicer guy, either,” Joe added. “Unassuming, down-to-earth—a real gentleman.”

Of course I had to know more, and when Joe called Bert at his office in Ruston, Louisiana—the place where he grew up and still makes his home—he assured Joe that he’d be more than happy to talk dogs and bird hunting with me. When I finally caught up with him on his cell, he was en route to his quail camp in the West Texas caprock country, pulling a trailer loaded with a dozen pointers and setters and his good walking horse.

Bert Jones proved to be everything Joe Augustine made him out to be, only funnier. At one point during our conversation, he pulled to the side of whatever lonesome highway he was on in order to snap a picture of a bizarrely indescribable piece of West Texas architecture, or installation art, or something.

“You’ve got to see this!” he exclaimed, texting me the photo. I have no idea what it is; the wreckage of an alien spacecraft, possibly, or maybe a temple devoted to the cult of Marilyn Monroe.

Bert was still processing the odds of running into a man leading a pack of field-bred English setters through the heart of Manhattan.

“I was only in New York for a day and a half,” he marveled. “I’d had lunch with my friend Ernie Accorsi, the Colts’ GM when I played there in the ’70s. He’d just retired after a long career in the Giants’ front office.

“Well, it was a nice day, so I decided to walk back to my hotel. I saw Joe and his setters and thought, ‘What in the world?’”

I asked Bert how many dogs he owned at the moment, and after doing a little mental math, he came up with a total of 18—13 setters and five pointers.

“Three of them are old-timers who now live the life of leisure,” he explained, “and I have four year-old setter puppies that I’m just starting. I typically like to keep twelve to fifteen dogs in my string.”

He’s always had pointers and setters— sometimes more of one, sometimes more of the other—but he’s also kept a few Brittanies over the years, and even a red setter or two. It’s not about breed for Jones; it’s about having the talent to make the team. He has a three-acre “running pen” at home where his dogs are exercised every day, and while technically he does his own training, he insists that what he really does is let their genetics train them.

“I allow them to do the things they were bred to do,” he explained, “and once they figure that out I try to stay out of their way. They have to want to please me, of course. They learn that if they make me happy, I’ll make them happy.”

Two of Jones’ 13 setters and five pointers pin down a covey in the Texas brush country.

The West Texas landscape is big, hard and unforgiving, and to hunt it effectively you need a lot of dog. It’s not at all surprising, then, that Jones’ tastes run to tough, wide-ranging dogs with good noses, a ton of stamina and the ability to handle birds that are far more apt to hoof it than to hold. He likes a dog that hunts with a high head, too, his experience being that they’re the strongest bird-finders. They have to honor another dog’s point, of course, and while they should make an honest effort to find dead and crippled birds, Jones is willing to cut them some slack on that score.

“You don’t get the total package with every dog,” he acknowledged. “Sometimes you only get part of the package, so you learn to adapt and work with what you have.”

Sort of like quarterbacking a football team, if you’ll pardon what may strike you as a painfully obvious analogy.

Jones grew up during an era when Louisiana still offered what he described as “old-style Southern quail hunting.”

“We hunted the pea patches, the field edges—all the classic spots,” he said. “We hunted both on foot and on horseback, and Daddy always had great bird dogs, mostly pointers in those days.”

His earliest quail hunting memory is of a horseback hunt when he was about five years old. “There were seven kids in our family,” he recounted, “five boys and two girls, and Daddy would grab whoever was little enough to pick up with one hand and sling him or her on the back of his saddle.

“Well, that day it happened to be me, and after a while the dogs went on point. It was on kind of a sand flat, and when Daddy got down to go to the point, the horse suddenly started rolling around on his back! I started screamin’ and hollerin’, so Daddy had to leave the dogs to see what all the fuss was about.”

Clearly bemused by the memory, Jones added, “Daddy’s never let me forget that I made him miss that covey rise.”

Bert’s daddy, by the way, was a pretty fair country ballplayer in his own right. A star halfback at Tulane, Dub Jones enjoyed a long career in the pros, mostly with the Cleveland Browns, and as his son proudly points out, he still co-holds the NFL record for most touchdowns in a single game—six.

Oh, and remember me mentioning that Bert was the second overall pick in the 1973 NFL draft? I’ll give you one guess who the second overall pick in the 1946 draft was. Here’s a hint: It wasn’t Sammy Baugh.

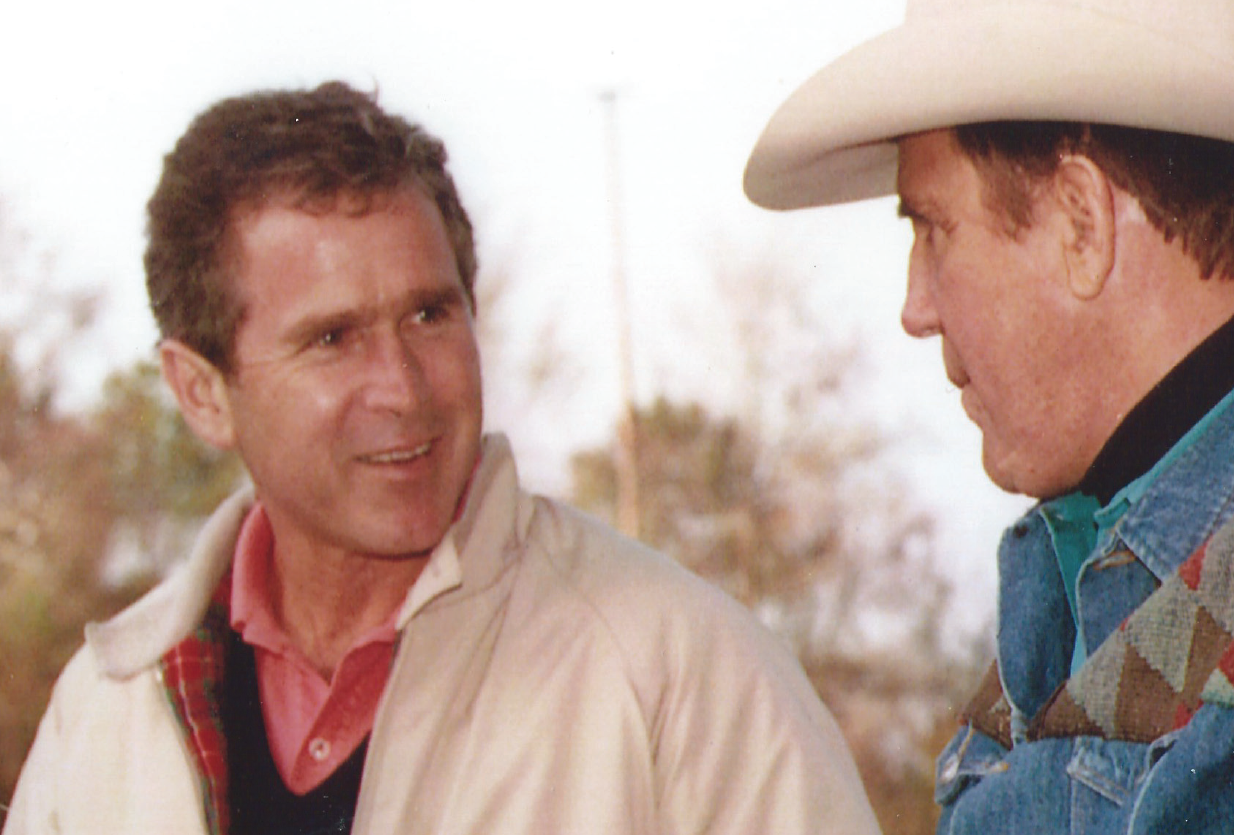

NFL great Bert Jones and his father, Dub, now 95, ride out for a morning’s hunt on Bert’s quail lease in West Texas.

Not only is Dub still kicking at age 95, he still climbs on the back of a horse now and then to hunt quail. When he was in his prime, though, the man was a quail hunting force of nature.

“In 1985,” Bert said, “I ran the New York City Marathon. So I was in shape. Then I went quail hunting with Daddy— and I thought I was going to die! One of the things my brothers and I learned is that when Daddy dropped a purple onion and a can of sardines in his vest, we were in for a long day.

“We’ve refined our taste in lunches since then, although I did learn to like sardines. Purple onions, not so much.”

Once the hunting played out around home, the Jones boys crossed the border into Texas. They had a lease near Fort Worth for a while, and then, in Bert’s words, “moved west with the quail.” They’ve been at their current spot in the caprock country since the mid-1980s; what Bert calls his “quail camp” is a former ranch house near the lease to which he added a 20-run kennel.

Bert let me in on his two surefire methods for sniffing out good quail hunting when you’re a stranger in town. One is to find “the busiest filling station at the busiest four-way intersection,” go in, and ask around. Chances are there’ll be other hunters who can point you in the right direction. The other is to locate the most successful insurance agent in the area, the one who writes the policies for the local ranchers. That’s how they found the lease they’re on now.

“It was one of the few times Daddy ever purposely dropped my name,” Bert laughed. “He said ‘My son Bert here just retired from the NFL, and he’s interested in a place to hunt quail.’ The guy said, ‘I never heard of your son, but if you’re looking for quail hunting, I believe I can help you out.’”

I asked Bert if he has any blue quail on his lease, and his reply echoed the sentiments of a lot of bird hunters: “I do—but I know where they are and I stay away from them.” This puts blues in the same category as sandburs, which he also has, and also avoids.

Like every other hunter in Texas, Jones suffered through a five-year drought when there were no birds to speak of—and like every hunter who kept the faith, he’s reveling in the upsurge that commenced a couple seasons ago. He’s emphatic, though, that the really gratifying part about having “good birds” is what it does for the dogs. For the veterans, it means abundant opportunities to polish their skills and put them on full display; for the rookies, it means giving them the reps they need to learn from their mistakes, gain maturity and confidence…and figure out how to make their owner happy.

“I’ve had a lot of great dogs,” Bert reflected, “and I’ve learned that you can’t replace them. You can only add to the memories. I’ve found in my old age that I’m narrowing my vices. I like to hunt bobwhite quail on horseback behind my dogs, and I like to fly fish in saltwater. It’s pretty fine stuff.”

We chatted a little while longer, and as Bert drew nearer to his quail camp for what would be his first hunt of the season, he exclaimed, “Ooh, this country’s lookin’ good. I’m really excited to turn out these puppies and see what they’ll do.”

However you define “bird dog man,” that statement alone should tell you that Bert Jones passes the test.

This fascinating anthology showcases 38 wonderful stories from those halcyon days when sporting gentlemen pursued the noble bobwhite quail with their favorite shotguns and their elegant canine companions.

This fascinating anthology showcases 38 wonderful stories from those halcyon days when sporting gentlemen pursued the noble bobwhite quail with their favorite shotguns and their elegant canine companions.

The 368-page book opens with compelling tales by the literary giants from quail hunting’s golden era, including Nash Buckingham, Robert Ruark, Havilah Babcock, Archibald Rutledge, and Horatio Bigelow.

The book’s second section presents reminiscences by sporting scribes of the modern era, among them Jack O’Connor, Gene Hill, Joseph Greenfield, Dave Henderson, and Mike Gaddis. The third section is comprised of unforgettable short stories on quail hunting and bird dogs by James Street, Bob Matthews, Dan O’Brien, and Caroline Gordon.

Will the sweet sound of whistling wings, the heart-stopping beauty of a sunset point, the timeless partnership of a man and a dog wise in the ways of wild birds ever return? Perhaps, but for now we can rejoice in the fact that we can, through the writings of some of the finest sporting scribes America has ever produced, experience those golden days vicariously. Buy Now