There was once a land with no people, no mammals, just forested mountains and clear rushing rivers since the rocks were laid down. No deer or antelope, no wolf or bear had ever left a footprint there. That place lay brooding for millions of years, a thing unto itself.

Egypt, Greece and then Rome rose and fell but still that far country remained untouched. Just a thousand years ago — with Europe already on its first crusade to Jerusalem — and still none had ever laid eyes on those virgin shores.

At last, inevitably, a sea canoe grated on sand. Those first people called it Land of the Long White Cloud. Europeans came much later and named it New Zealand, the last country to be inhabited by man. Its story would be like no other.

When British settlers arrived they sensed boundless possibility but also a great emptiness. Those pioneers viewed deer, trout and game birds as basic necessities, and so for years they fought every hardship to bring these animals to this farthest edge of the world, to this place void of game species.

Fish came early. Brown trout were introduced in the late 1860s, proof that life will make its move, given half a chance. Within a few years a brown of 50 — yes, five zero — pounds was speared. Sometime later a batch of rainbow trout ova, all carefully packed in ice, survived the long voyage from Sonoma Creek, California. They too seized the moment, creating a world famous fishery around Lake Taupo and its rivers. There were highs and lows — the vast schools of bait fish fell and trout sizes declined as predator and prey found balance, yet the fishing still staggered belief. One angler’s catch of 11 trout included 10 weighing more than 20 pounds.

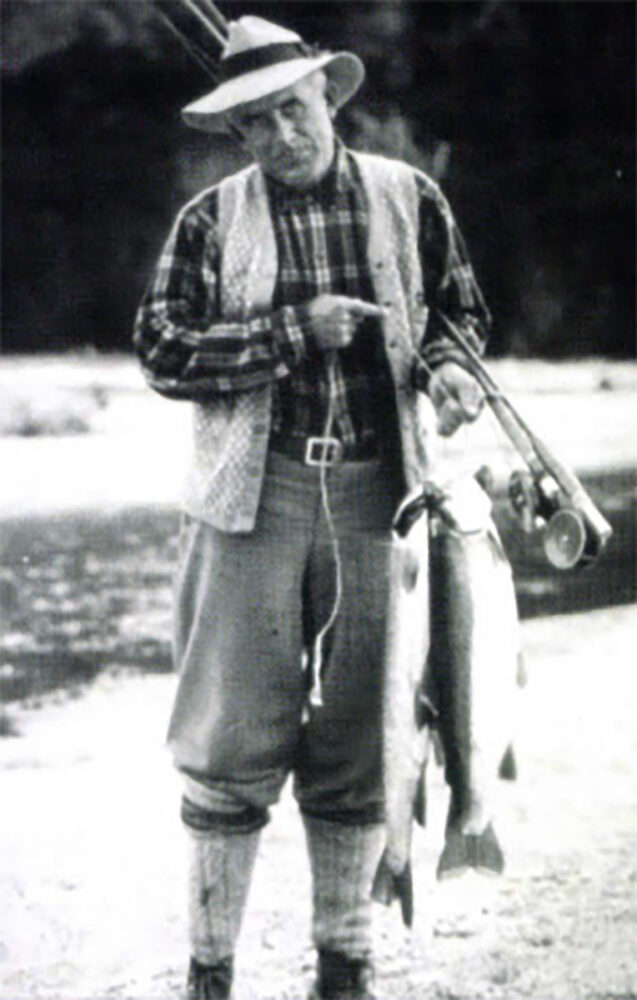

Zane Grey with descendants of Sonoma Creek, California Rainbows caught in the Tongariro River. Photo Courtesy of NZ Herald.

Even in those far off times word spread fast in the fly-fishing community. Zane Grey made the first of his three visits in 1926, and his party was taken by a Maori guide to the Dreadnought Pool on the Tongariro River. Grey went on to popularize his adventures in a runaway success, Tales of the Angler’s El Dorado.

Grey’s literary strength lay in action and colorful description, not tact. It’s not well known that he tried to buy the Tongariro. The bewildered locals had no idea what to say, but it struck a nerve. They’d left England to build a nation where any man could go catch a trout if he put in the effort. There would be no more locked-up rivers. Other, more practical barriers, got in the way. Nobody had ever tried to buy a river in New Zealand before, and nobody had said the Big T was for sale anyway. The deal fizzled, and to this day the custom of the Queen’s Chain still applies on many waters — any angler can access a riverbank to the width of a surveyor’s chain, 22 yards.

Brook trout came too and while many eggs died at sea, enough survived. Fish topping six pounds have been caught, with select lakes on the south island being the best bet.

Gamebirds were not neglected either. Mallards proved tricky, and it wasn’t until a large number of birds and eggs came from the U.S. in the 1930s — some by the new-fangled “flying boat,” that greenheads had well and truly arrived. They went on to become a hunter’s staple, with daily limits up to 25 per hunter.

Canada geese arrived, some say as a gift from Teddy Roosevelt. They became so common in some areas that today there is no season or daily limit. California quail likewise spread well, enough to kick-start a small industry. One shipment of frozen New Zealand quail bound for London totaled 20,000 birds, and local sportsman George Elliot went on to shoot 28,666 quail between 1900 and 1973. There is no record of how Mrs. Elliot felt about this achievement, though I can guess.

Red stag came from Britain, mostly from great estates like Windsor Park. Other releases came from the pure wild deer of Scotland, with the result that New Zealand is now famous for red stag. Many outfitters offer preserve hunting and do it well, but it’s less well known to visitors that wild deer are still common. The odds are better than ever for a traveling hunter with the right connections to take home a wild trophy.

The Otago herd came from the wild Scots deer of the Highlands, but they’ve always grown larger in New Zealand. Natural elegance and symmetry are their chief hallmarks and trophy quality is superb. This is the same bloodline hunted by Jack Forbes and other early legends. Quietly spoken, Jack was 40 when he began to stalk, but went on to string together a series of spectacular wild trophies. He favored the .318 Westley Richards, forgotten now but hip as they come in the early 20th century.

It’s scarcely possible to measure the breadth of Teddy Roosevelt’s vision, not just for America, but for the world at large in matters both great and small. As President, he was a busy man, but more than anyone, TR understood what it is to be a young country in the bright morning of its life. Perhaps the last virgin place stirred something in him. He summoned up three bull elk and seven cows from the National Zoological Park in Washington DC, to be gifted to a far southern land he would never visit. If you dig deep enough, it turns out they came from TR’s beloved Yellowstone, whose elk he knew and loved uncommonly well.

Ten more elk of Yellowstone stock were freighted by train to San Francisco. With an epic voyage already behind them, they faced another 6,000 hard miles at sea. Just before their arrival the ship hit a storm so severe it broke the backs of two animals. From there they travelled south by steam yacht to George Sound, Fiordland. The year was 1905.

Fiordland, a south island wilderness of three million acres, is a land of sweeping glacial valleys and cold rainforest, where tall waterfalls plunge down steep rock. In some places it can take an hour to move just a handful of yards. Back then, vast swathes of Fiordland were blank on maps, simply marked unexplored. Rainfall runs up to a ridiculous 400 inches a year, biting insects are fierce and there are no roads. Even today aircraft lost there may never be found. A census in 2013 showed a population of 40 people in an area the size of Kuwait.

E.J. Herrick in 1929 with first New Zealand moose taken on license. Photo courtesy of Herrick Family.

The first elk licenses were issued in 1923 and over the coming decades local adventurers would take scores of top-quality trophies. It was tough going even for hardy settlers. In a typical episode, noted hunter Eddie Herrick spotted a good bull too late in the day to stalk, so he and his companion sat through the night in cold, heavy rain without tent or gear. The next morning Herrick killed the bull, one of five over 55 inches he would take out of the big valleys during his career.

At its height, Fiordland grew elk as big as any that walk the Rockies. A shed better than 64 inches was found on a high saddle in country so remote that the bull was never seen by human eyes.

In 1949, the New Zealand-American Fiordland Expedition ventured out to study the elk herd. Too late, the environmental tide had turned around the world. Within a decade the Noxious Animals Act was passed and the introduced elk began a slow retreat. Unrestricted shooting, competition for browse and crossbreeding with red deer eroded half a century of hard work.

In recent years, the Fiordland Wapiti Foundation has culled more than 5,000 red deer from the region, which has resulted in a steady increase in the quality of wild elk. But even today, the secluded valleys are tough going for hunters and a system of unit allocation carefully regulates the number of elk taken.

If there is a Single Story that captures the paradox of failed introductions — youthful enthusiasm at the beginning and abiding sorrow at the end — it is that of moose. Four bulls and six cows from Saskatchewan were released at Dusky Sound, Fiordland in April 1910. It was a bold move. No moose had ever seen the southern hemisphere before, and for the next 19 years they simply vanished into hostile wilderness, with only scattered reports to confirm that some were alive. Eddie Herrick, also using a .318 Westley Richards, felled the first legal bull with a single shot in the Seaforth Valley in 1929.

It just wasn’t moose country. Only two bulls would ever be taken under license, both by Herrick, and none would ever be of great trophy quality. Government protection faded in the ’30s and by then it was generally believed the moose were gone for good. Everyone was surprised when some cows and a bull were killed in the 1950s an ad a scattered handful of photos were taken of live moose. Those ghostly monochrome images of the big animals struggling so far from home have a profound and melancholy quality, moments caught in time from a battle that could never be won.

There was a tantalizing account of two moose taken about this time by a pair of Americans, but the names of those adventurous souls somehow slipped through the fingers of history. Then, just as suddenly as before, the moose disappeared, though a few wild, strange stories still swirled. In 1971 the rumor of a bull being taken rippled through the tiny communities. Nothing concrete emerged but a shed antler was found. At long last the curtain had come down.

There is a footnote, perhaps the final one, perhaps not. In the fall of 2001 unusual tracks and a bedding site were found and some snagged hair were recovered. DNA profiling confirmed the impossible. Ken Tustin, a former government hunter turned research scientist, has done more than anyone to capture an image of the last Fiordland moose standing. Something about their story must have touched him, to spend months at a time in those somber, tangled valleys. If he ever succeeds in his quest, he may tum out to be the greatest hunter of us all.

The early game introductions were full of these crooked paths. Tahr, the mountain goat of the high Himalayas, were originally captured for Woburn Abbey estate in England in 1897. Their offspring would make the long voyage to New Zealand in 1904, but the journey was not without drama. The tahr were under the care of the ship’s butcher, who lost control of one of the bulls. It raced around the deck and finally flung itself into the sea, but the rest of the herd went on to find their freedom at last in the Southern Alps.

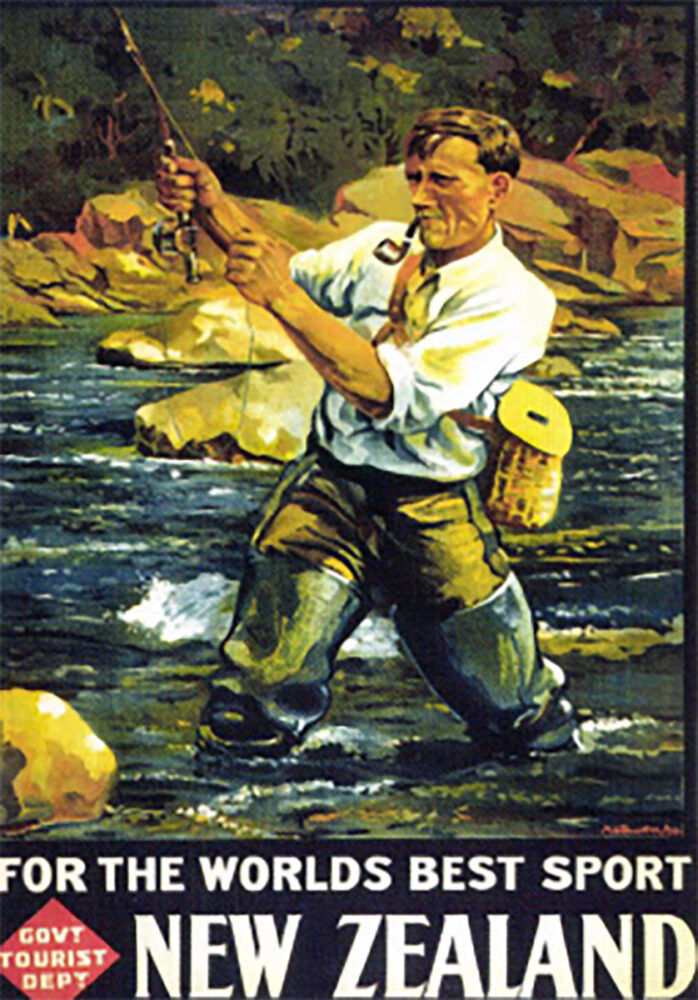

Early promotional poster issued by NZ tourism.

Early sportsmen were startled at the sight of bull tahr on a ridge, his thousand-yard stare and great mane ruffling in the breeze and speaking of pure wilderness. They were surprised to see the herds sprint over icy rocks. Tahr will launch themselves across vertical cliffs and leap fathomless voids. Trophy quality today is excellent, the best in years.

Sika, the elegant spotted deer of China and Japan, also came from Wobum Abbey. They have been part of the north island hunting scene for a century. Smaller but more competitive than reds, their refined features make them highly sought-after. World class trophies are taken every year and most of the best still come from the wild.

Chamois arrived at about the same time, a gift from Austrian Emperor Franz Josef. From that first stocking they spread quickly across many parts of the south island. The chamois is a graceful alpine animal that today is enjoying its highest numbers in years.

What else? Fallow have spread across New Zealand since the early days. The massive sambar, the bongo of the Pacific, turned out to be the quiet achiever. Trophy quality is high but they are crafty, as you might expect from a deer that was tiger food back in India.

It was inevitable that white-tailed deer would be part of the story. They came from New Hampshire, a state not noted for big racks, and some records point to TR again. It would be the longest journey ever taken by whitetail. Eighteen made landfall in the late summer of 1905, and some went to the sweeping beech forests around Lake Wakatipu.

Today, large ranches around the head of the lake run guided hunts, but deer numbers remain modest. Another herd is on Stewart Island, a remote place of wild, empty beaches and thick bush, altogether a far cry from the whitetail’s homeland. There is nothing south of the island until Antarctica. At times the aurora australis, or southern lights, stream overhead in the night.

A tahr hunter traverses a snowy slope in July, midway through New Zealand’s winter.

The trophy quality of New Zealand’s whitetails has never come close to any U.S. records, but maybe that’s not the point. The appeal lies not in what they might score but the message they carry: No matter how far from home, how difficult the conditions or how forgotten they may be, they have endured. The list goes on . . . chukar, pheasant, wild hogs, rusa deer, black swan. There’s no denying that some imports were made with more enthusiasm than sense, but those pioneers were living a philosophy that Roosevelt would later make famous — do what you can, with what you have, where you are. New Zealanders believed they were building a sportsman’s paradise for the benefit of their new nation. It couldn’t be done today, but the past is a foreign country — they do things differently there.

Stories about salmon are difficult because there is no fairytale ending. They journey upstream to die, but also to create life, so it’s hard to say if it’s an end or a beginning. The Winnemem Wintu of California were a salmon people, who took issue with the capture of some of their beloved chinook in the 1870s. They eventually came to terms with change but a covenant was made. Some eggs were taken for breeding, but the vast shoals would always be able to come home to the cold waters of their beloved McCloud River.

It didn’t pan out. During World War II a 600-foot dam flooded the river. The chinook could no longer make their urgent journey home and the promise was broken. But life is tenacious. Some had already travelled to the far side of the world and today they still run up big, cold rivers with ringing names — the Rakaia, the Rangitata, the Waitaki. Their bloodline has remained pure.

Not long ago some Winnemem made their way to the south island to hold their first salmon ceremony in 60 years. They danced for four days, asking the salmon for forgiveness. They want their fish back and sang into the night to apologize and make it so. New Zealand has the genes. The McCloud is still there, and water always wins in the end. Somehow that story, that circle, isn’t done yet.

The chinook are one unknown story among many. The tales are endless but the lessons are often the same — much of the sporting life of the last virgin land was built on an alliance across the Pacific. Today, few people on either side understand that there’s a certain rightness to North American sportsmen making the long journey. TR and Zane Grey would have approved.

Editor’s Note: This article is an extract from Pete Ryan ‘s book, Wild South – Hunting and Fly Fishing the Southern Hemisphere, which covers Africa, Australia, New Zealand and South America.

This book is a selection of some of Grey’s best work, and the stories and excerpts reveal a man who understood that angling is more than an activity–it is a way of seeing, a way of being more fully a part of the natural world. No writer exceeds Zane Grey’s ability to integrate the fishing experience with a world he saw so vividly. Buy Now

This book is a selection of some of Grey’s best work, and the stories and excerpts reveal a man who understood that angling is more than an activity–it is a way of seeing, a way of being more fully a part of the natural world. No writer exceeds Zane Grey’s ability to integrate the fishing experience with a world he saw so vividly. Buy Now