The valley was long and narrow, filled with the green of rich grass and the pale gold of frost-touched arctic willow. Along the edges of the valley was a thick border of spruce, but not far up the mountainsides, the woods played out in a scattering of scrubby trees. The hillsides flamed with the scarlet of scrub arctic birch that was now in its autumn glory.

At the head of the valley, perhaps four or five miles away, was a series of high ridges and basins rapped by a conical peak dusted with snow. Below it lay green upland pastures of moss, grass and lichen cut by ragged streaks of gray slide rock.

“What about those mountains at the end of the valley?” Bill asked. “They’re my idea of sheep country.”

Sam Williams, a slightly built, intelligent Indian who was one of our guides, considered the question momentarily.

“Maybe so,” he said. “One time two or three years ago when I come here to shoot moose, I see some sheep there, but the country where we go is better. More rougher. Sheep like more cliffs. Want to run away from the wolves.”

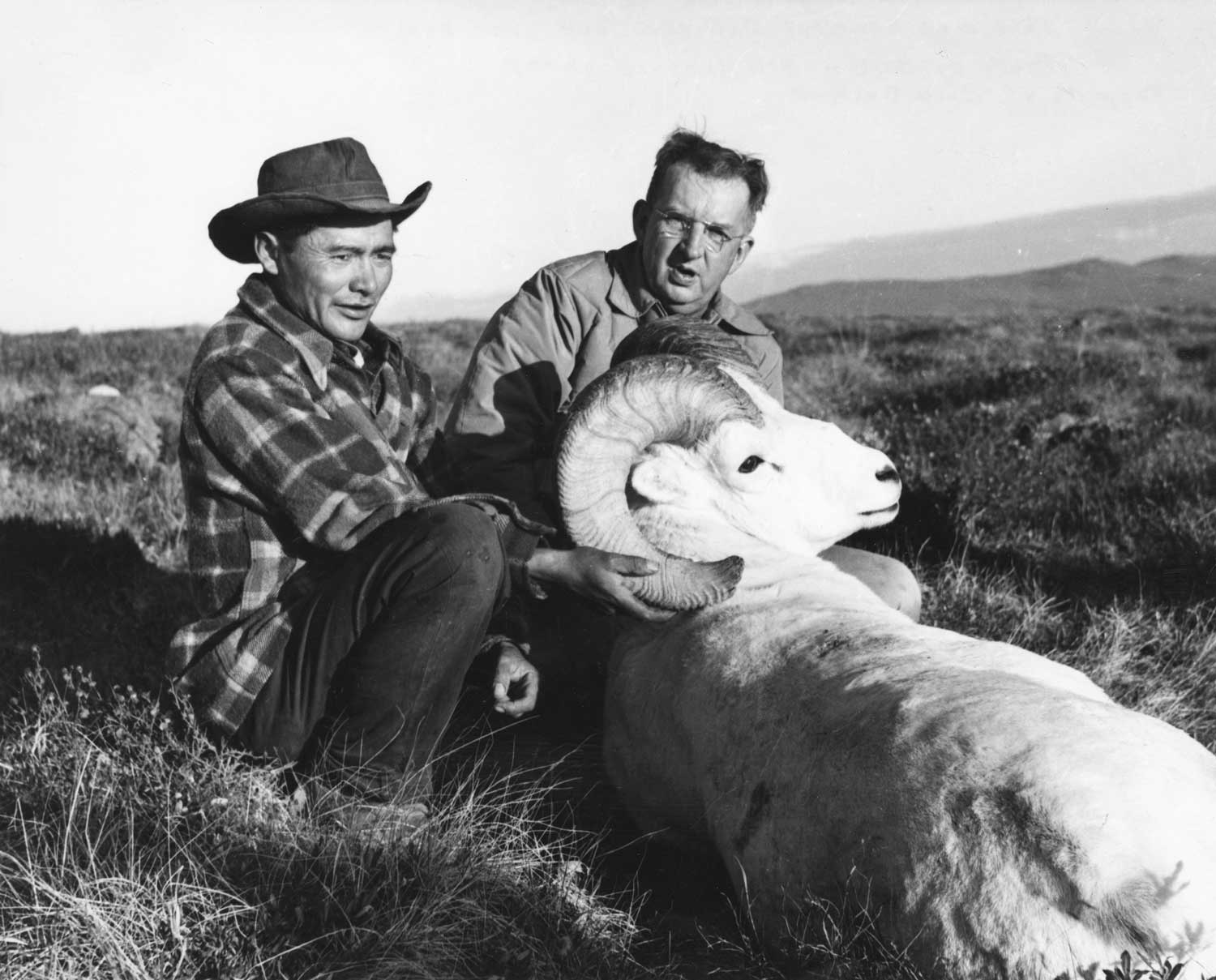

Bill Rae, then editor of Outdoor Life, and guide Sam Williams pose with Rae’s first-ever Dall sheep. The ram’s horns were the heaviest that O’Connor had ever seen.

The Bill who was with me on this white-sheep hunt is the editor of Outdoor Life. Bill Rae is a big curly-haired Bostonian who has followed the newspaper and general magazine route from Harvard to the editorship of Outdoor Life. He had traveled and hunted in the East and South, had shot elk in Wyoming, but this was his first jaunt into Canada’s Yukon Territory as well as his first sheep hunt.

My other companions on this 30-day trip were likewise out after sheep for the first time. One of them was Red Cole, sales manager of Cleveland’s Warner and Swasey, the great machine-tool company. The other was Fred Huntington, the good-natured and rotund manufacturer of RCBS loading tools and dies in California. The object of our expedition was what is acknowledged to be one of the world’s great trophies: the beautiful white Dall sheep of the Arctic and Subarctic.

Harold Chambers scans a sheer mountain slope for Dall sheep.

When we glassed those mountains, we’d been on the trail two and a half days by pack outfit. After flying from Seattle to Whitehorse, the largest town in the Yukon, we were taken by our outfitter, Alex Davis, 100 miles to the end of the road at Aishihik Lake, where the Canadian government maintains an emergency landing field. There, we met our pack outfit and headed north over an old Indian trail toward the remote and isolated Dawson Range. We had three guides, a cook and two horse wranglers.

Our head guide was Harold Chambers, who had been a horse wrangler when Herb Klein and I hunted in the Yukon in 1950. Harold is a one-time rodeo rider who can pluck a handkerchief from muskeg without dismounting, glass the countryside while standing on his horse’s back and lift a tree-size deadfall from the trail singlehandedly (he did have to dismount for that).

In the Yukon, fall begins about the middle of August and by the first of September, when we started out, it’s well advanced. Willow, cottonwood, alder and arctic birch (which the natives usually call “buckbrush” or “bugbrush”) turn with the first frosts, and almost always the higher hills are dusted with the snow of some early storm. Even when we left the road to head into the backcountry, we had frost every night and, in the mornings, we had to break ice in the water bucket by the cooktent.

That night, after we’d pitched camp on an old glacial moraine above a river, I glassed the low mountains above timberline. Once, so far away that it was only a dot completely without form through 12x binoculars, I saw something moving just below a ridge. From the way it would walk a few steps, stop and then move again, I decided it must be a grizzly digging for ground squirrels. A little later I spotted a cow moose and calf about two miles off.

“See anything?” Bill asked when he’d finished blowing up his air mattress and making our tent snug for the night.

“I think I saw a bear, probably a grizzly,” I told him, “and a cow moose with a calf just went over the saddle.”

“Call me when you see some sheep,” he said.

Head Guide Harold Chambers leads his pack string across a wilderness stream during O’Connor’s 1956 sheep hunt in the Yukon Territory.

On the fifth day, we toiled over a high rolling range where the bleached skulls and antlers of wolf-killed bull caribou showed white above willow and arctic birch. We were far above timberline when we reached the divide. Below us, we could see a silver stream meandering through willow, muskeg and golden meadows of frost-cured grass. It was four or five miles away and Sam told us we’d camp there that night. To the north, the country rose steeply, becaming harsh and rugged. The whole uplift culminated perhaps 20 miles away in a black ridge dominated by a huge dark peak streaked and spotted with snow.

Sam, who had latched onto my 12×60 Leitz binoculars, glassed the mountains lovingly.

“Big mountain called Prospector Mountain,” he told us. “We go there to hunt sheep. All the time big rams there.”

And we all looked at it as if it was the promised land. I had made several trips to the Yukon and northern British Columbia for Dall and Stone sheep, but this part of the Dawson Range was new to me. It would be hard to find in all of North America a wilder and more isolated piece of country.

Years ago, Indians came to hunt, but the Indian population in the Yukon is decreasing. What’s more, many Indians have moved into Whitehorse, where they take jobs and forget the old ways. The low price of fur keeps the trappers out of the mountains. A few American big-game hunters have gone into the Dawson Range and sometimes a prospector seeking his fortune, but for the most part, the country is as wild and lonely as it was when Columbus discovered America.

We rode on from the Klaza River to pitch camp along Magpie Creek, a clear and lovely stream full of grayling. There were moose in the hills, ptarmigan in the scrub arctic birch on the hillsides and the camp itself was full of grizzly sign—claw marks higher than our heads on the trees, grizzly hair caught in the rough bark. The big bears had dug out the garbage pit where the refuse from a camp of a year ago had been buried, and they had chewed up tin cans to get the trace of syrup in them.

It looked like a good spot for a hunting camp, but at breakfast when I suggested we stay there, Bill, Fred and Red all chorused a thunderous, “No!”

“Haven’t you heard?” said Fred. “The bears are beginning to fight back.”

We split the outfit. Bill, Red, Fred and I, along with Harold Chambers and his brother, Freddie Chambers, one of the horse wranglers, and Sam Williams would push on that day into sheep country and make a jackcamp far above timberline and within easy striking distance of the sheep. The rest of the outfit would head for a new main campsite.

We cut away from the trail, followed by our three packhorses, and pushed high over the ridges toward fabled Prospector Mountain. A good many years ago, the great northern caribou migration had gone through this country, and that day we must have seen 15 or 20 bleached caribou skulls with antlers attached. Flocks of ptarmigan, now half white and half brown in their intermediate coats, flew squawking and protesting away, and once, when our outfit dipped into a narrow valley where there was a little timber, we saw half a dozen blue grouse.

Midafternoon found us scrambling up a ridge about five miles from the towering, dark-gray mass of Prospector Mountain. We tied our saddle horses to willow shrubs, let the pack animals shift for themselves, and toiled afoot up the last few hundred feet of the ridge.

We had hardly got settled when I heard Sam say, “Sheep!” and Harold answer, “I see them, too!”

I lay down and with my old 9x binoculars, quickly picked up a herd of seven sheep feeding in a saddle just above a big black cliff across the valley. A half-mile or so to their right were three other sheep.

Bill Rae lay beside me and started using his binoculars.

“See them?” I asked.

“I see a lot of little white dots, some moving now and then.”

“Those are your Dall sheep,” I said.

“Well, I’ll be darned . . . Are they rams or ewes and lambs?”

“My hunch is they’re rams because they’re all about the same size. In a band with ewes and lambs, we could see the difference in size, even from here, and the little lambs would be frisking around.”

Sam was on a rock above me with my big 12x binoculars. I borrowed them from him, but I still couldn’t tell whether I actually saw horns or I thought I saw them. I could definitely see that one of the sheep wore a light gray saddle. We were, I knew, approaching the area where the snow-white Dall sheep begin to show some of the characteristics of their dark cousins, the Stone sheep. I had suspected that we’d find white Dalls here with the black tails of Stone sheep and a scattering of other dark hairs here and there. I was surprised, however, to see this one with a gray saddle.

Harold Chambers had scrambled down off the rocks a few minutes before, and now he returned with a 20x spotting scope, the real medicine for sizing up a head of any sort at long range.

“Ah, by golly,” he said gleefully, “They are rams!”

One by one we took turns looking at the sheep. Through that wonderful optical instrument our sheep were tiny toys against green grass and black slide rock, the whole view softened by the purple haze of late afternoon. I suppose they were at least two miles away, but we could see that all were rams. Those I could see were not large.

It takes from 10 to 13 years to grow a real trophy head on a wild ram, and these looked to be a bunch of youngsters, from 2 to 7 years old. I could see the horns on the saddleback quite well. They were thin and sharp and didn’t come to the bridge of his nose. I guessed him to be a 5- or 6-year-old with a curl of from 30 to 32 inches.

“Maybe some big ones around. We take another look tomorrow,” said Sam.

“What do you think of your first white sheep?” I asked Bill as we led our weary horses down into the above-timberline basin where we were to camp

“Beautiful!” he said “It’s worth the trip from New York just to see them. And once you’ve seen ’em, you’d never confuse them with anything else white. They’re almost luminous. I can hardly believe we may get a shot at one tomorrow.”

He was voicing the feelings of all of us. The sight of those sheep had lifted our morale tremendously. We had been traveling by horseback eight hours a day for six straight days, making a new camp every night, each day packing and unpacking 26 horses.

We spent a chilly night in a clump of willows by a little stream that trickled through the stones from pothole to pothole. We had apparently run a family of moose out because everywhere we found droppings and signs of browsing. It was bitterly cold that night. We were at 6,000 feet and in the subarctic. Before we turned in, frost glistened on the willows and the misty, glowing streamers of the northern lights played across the sky.

The next morning, we broke ice in the little stream to wash our faces. Then we gulped searing coffee, devoured fried egg sandwiches, and were riding away before the frost was off the grass. We dropped into the big valley that we’d looked across to see the rams the night before, then pushed our outfit up the side of the mountain and under the slide rock where we had seen a couple of the rams.

We didn’t want to blunder into the sheep, so we’d stop short of the top of each rise and glass ahead before we moved on. The sun was well up by now. It was warm in the hollows, but on the ridges the wind was chilling.

Sam had told us it was sheep country, and it was. Ram tracks and droppings were everywhere, and the beds the herd had pawed out in the shale were so fresh I could smell the characteristic sweetish-greasy odor of wild rams.

No sooner had we topped the main ridge than we saw sheep. Half-a-mile to our left a ram was feeding on the top of a little rise. Below him, two others were bedded, chewing their cuds and gazing off into the distance. Far to the right, and at least five miles away, we could see 70 or 80 little white dots against the green of a lofty pasture. This we knew was an ewe-and-lamb herd. Then Fred spied a lone white dot in a big basin a couple of miles away.

“That’s a sheep,” he said, “but what kind?”

“Old ram,” I told him. “Some crusty old boy with a lot of bad teeth, arthritis and gallstones. He’s probably so mean the other rams have booted him out.”

“Let’s turn Bill loose on that one,” Fred suggested.

“Good idea,” I agreed.

Wild sheep are like human beings in that animals of the same approximate age generally travel together. The sheep hunter will usually find young rams in one bunch, old-timers with big heads in another. Often in his last days, a very old ram will range alone.

We found a very sharp outcrop that was ideal for looking over the herd of rams we’d seen the previous day. From what I had seen earlier, I didn’t expect to find any trophy rams among them. They were now less than 300 yards away and for an hour we feasted our eyes on the beautiful creatures.

Superficially, all the sheep looked pure white, but when they turned their broad, fat fannies toward me, I could see that they all had black tails. With the 12x binoculars, I could see that a couple of the rams had considerable shading of black hairs around the eyes and on the bridge of the nose. The gray-saddled ram we’d seen the night before was about like the average light-colored Stone ram I’d seen in 1951 when I hunted in the northwest corner of British Columbia.

Red had his .300 Magnum rested in a notch in the knife-sharp ridge and was gazing hungrily through his 4X scope at the sheep.

“I could clobber that saddleback,” he said. “What do you think? Should I take him?”

“Maybe better wait. I think you see better one.” Sam cautioned.

All these young rams had slender horns of no great length. We’d leave them to grow up for another hunting party and another year. But in the meantime, we had a stalk to make so we could get a better look at the lone ram. Then maybe Bill would have to go after it. We likewise had to locate the main camp.

All the time we’d been glassing the young rams, the lone sheep in the big basin had stayed within a radius of a few hundred yards. For a long time he fed. When he bedded down, we started our stalk.

When we were about a mile from him, we could see with the 12x binoculars that his body was huge, but we couldn’t tell much about the head. Bill, Harold, Sam and I climbed up on a rocky outcrop and set up a spotting scope.

“Old ram, massive head, but broomed,” Harold said.

“It would look pretty fancy on the wall of my office,” Bill said when his turn came to peer through the spotting scope.

Then I looked. It was indeed a fine head: close-curled for a Dall sheep, massive, heavily broomed—a type more common among the great bighorns of the southern Rockies than among the Dalls and the Stones of the north.

“Is he shootable?” asked Bill.

“Very shootable,” I said.

Bill, Sam and I were to make the stalk. We’d ride up as far as we could and then leave our horses behind a ridge. The slope was a long one that looked gentle from a distance. In reality, it was so sharply tilted we were soon puffing.

Little Sam once told us he had undergone an operation that completely immobilized one lung, but you’d never know it. He could out-walk anyone in the outfit and the horses, too.

Now, as he paused to check cautiously on the ram, I heard Bill gasp: “Sam, your operation was a good thing for us dudes. If you could go any faster, you would leave me

for dead.”

Sam beamed but beckoned us relentlessly on.

When we got to the basin itself, the ram was on his feet and feeding, and we saw that we’d have to make the stalk with only the cover of scattered scrub willows or by staying below a gentle rise. Whenever the ram lowered his head to eat or turned away, we advanced. We snaked along on our bellies over the soft mass of grass, small shrubs and caribou moss that carpeted his lush mountain pasture. When the ram looked our way, we’d flatten out.

Now and then I stole a peek at him with my binoculars and, the more I saw of him, the bulkier he looked. When we were about 400 yards from him, he must have caught a movement. He looked for a long time directly at us. Then he began to feed again.

When we’d crawled a few yards farther, he jerked his head up and once more stared at us. He almost caught me with my hind end up in the air as I crawled, and he watched suspiciously. At this point, it was like trying to make a stalk on a baseball diamond.

I decided then that I’d better sit out the rest of the stalk. If I stayed behind, there’d be one less fanny sticking up in the air, one less chance the ram would see us. I was anxious to have Bill get his first ram cleanly, and anyone stalking his first sheep needs all the breaks he can get. I signaled Bill and Sam to go on without me.

Laying there, watching them worm up the mountainside, I wondered if Bill would catch ram fever. I’ve seen sheep give the shakes to many veteran hunters. The first ram I ever took a crack at in Sonora, Mexico a generation ago gave me the buck so bad I was almost helpless.

I got out my 9x binoculars to watch. The ram was still feeding and the wind still favored the stalkers, but the big boy was nervous. He’d feed for a moment, then jerk his head up and look. Bill and Sam were snaking ever closer.

The sheep was only a matter of yards from the head of the basin. If it spooked now, it would be over the other side and out of the country before Bill could get in position to shoot.

When they looked to be about 250 yards from the ram, I saw Sam motion for Bill to come up beside him. They had run completely out of cover. Through the glass, I watched Bill switch off the safety of his Model 70 Winchester .30-06 and settle down to bring the reticule of his 4x scope to bear.

When the first shot echoed through the basin, the ram ran a few yards and stopped. The second shot staggered the sheep, and now I could see a spreading red stain. As the ram moved off slowly, the third shot dropped him.

They were still lying there watching the ram carefully when I came up behind them. “Bill, you’re a sheep hunter,” I said.

Bill looked around wonderingly. “Is he dead?”

“Sure he’s dead,” I replied. “The second shot was the big one.”

We toiled up to the head of the basin where, a few minutes later, a happy guide and an exceedingly excited editor were bending over the largest and heaviest Dall ram I have ever seen. If anyone is interested in vital statistics, the ram measured 23½ inches from the hairline at the top of his shoulder to the bottom of his brisket, 47 inches from his chest to his rump. I have never seen a mule deer that massive, and the only larger ram I ever saw was a giant Alberta bighorn. Bill’s ram was white except for a black tail and a few scattered dark hairs on the bridge of his nose and alonghis spine.

The horns measured 15 inches around the base but were broomed clear back to the third annular ring. Heavy, rugged, massive, the head told of a long life and many loves and much fighting. He was a grand trophy. And now that the tension was over, we whooped and laughed and chattered as we took pictures, skinned out the cape and cut up the ram for packing.

Way back at the start of the stalk, Bill had discarded his white hat lest it be picked out in the sun by the ram. It wasn’t until he and Sam backtracked to look for it that we realized what an incredible distance we had crouched and crept and crawled. They were gone a long time and it was dusk when they returned.

It was the end of a lucky day. We knew that camp would be somewhere over the ridge on the bank of a little creek that was fed from the snows of Prospector Mountain. We thought we’d have to spend some time hunting for it. But when we topped the ridge, we saw the tents spread out white and neat below us and not more than two miles away. Ah, happy day! Now we had meat in camp and tomorrow the rest of us hoped to follow Bill’s suit.

New York seemed far away.

Note: This article originally appeared in the 2019 Sporting Classics Lifestyle issue.