That’s the thing about dogs: they don’t stew over what might have been.

One day in early March 2011 professional trainer Tracy Davis of Pavo, Georgia, loaded a couple young dogs onto her truck for some swim-bys. The swim-by, for those of you unfamiliar with it, is a drill designed to teach retrievers to stick to their line and stay in the water rather than succumb to the temptation to bail out and run the shore. This isn’t a big deal if your goal is a duck dinner, but if you aim to make a splash in field trials or hunt tests, a dog that holds its line is an absolute necessity.

It’s the mark, if you’ll excuse the pun, of a well-trained retriever.

The first dog Davis let out was a 1½-year-old yellow Lab named Feather. Athletic, enthusiastic, with a flying water entry and top-notch marking skills, Feather was a trainer’s dream. She’d earned her Junior Hunter titles before her first birthday; her owner, June Ashford of DePere, Wisconsin, had placed her with Davis so that her progress wouldn’t be interrupted by the northern winter, i.e., the “hard water” season.

Davis launched the bumper, sent Feather, and watched with satisfaction as the Lab performed like a champ. She made a beeline to the bumper, scooped it up, and made a beeline back. Feather was making it look easy, and when she had to leave the water, cross a spit of land, and re-enter on the other side — the crux drill — Davis was fully confident that she’d handle it perfectly.

Then Davis saw the water moccasin, and found herself hoping like she’d never hoped before that Feather would ignore her training and run the shore.

She didn’t, of course, and at that point stopping her would have been like stopping an arrow in mid-flight. Feather landed smack on top of the snake, taking it under and essentially trapping it beneath her.

The moccasin responded as its species has evolved to respond, biting her not once but multiple times on the inside of her right hind leg, injecting a massive quantity of venom.

Just imagining the scene — the water churned to a froth, the dog and the serpent locked in that terrible embrace — makes my blood run cold.

Now, the veterinarians in South Georgia know a thing or two about treating snakebites, and Tracy Davis broke every speed limit getting Feather to the nearest clinic … but the tissue destruction proved impossible to contain. They were able to stabilize Feather sufficiently for a friend of Ashford’s to give the dog a ride back to Wisconsin, where she was admitted to a state-of-the-art veterinary referral center. Even there, however, the necrosis could not be checked.

“It was like a flesh-eating bacteria,” Ashford recalls. “The skin and tissue just kept sloughing off.”

When it became obvious that Feather’s life was hanging in the balance, the hard decision was made to amputate the leg.

Still, when Ashford got the call telling her to come and get her dog, she thought they meant that Feather’s condition had deteriorated and there was nothing more they could do.

“Oh, no,” they corrected her. “She’s climbing the walls trying to get out of here. We need you to take her home so we can have some peace and quiet!”

The drama wasn’t quite over, though. A week into Feather’s recovery, a blood vessel burst in her stump, and, in Ashford’s words, “My house looked like the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.” Feather had lost so much blood by the time Ashford got her to the clinic that they had to carry her in on a stretcher, but she recovered from that, too — and on the day her sutures were finally removed Ashford gave her a 100-yard land mark, just to see what she’d do.

She nailed it.

This seems as good a place as any to note that Feather’s registered name is Cedar Creek’s On a Wing and a Prayer.

“It honestly never entered my mind to retire her,” says Ashford, who’s been competing in hunt tests with her Labs for close to 20 years and is prominent in obedience, agility, and rally circles, as well. “I wasn’t going to wrap her up in cotton; I was going to let her do what she loves to do.”

Not only does Feather love to do it, she does it exceptionally well. Since losing her leg, she’s earned both her Senior Hunter and Master Hunter titles — a significant accomplishment for any dog — and Ashford is pointing her toward the Master Hunter Nationals, the “Holy Grail,” in her words, for hunt test competitors.

“She runs faster than a lot of the other dogs out there,” says Ashford. “I’ve been to so many hunt tests where I’ll go to the line, send her for a retrieve, and after she’s finished a gunner will come in and say, ‘That dog only has three legs!’ And I’ll say, ‘Really? She had four when I sent her — what did you do to her?'”

Feather swims a straight line, too (in case you’re wondering), and in addition to her hunt test prowess she’s also a terrific pheasant dog. Not that that should come as a surprise, as her dam is a three-time Wisconsin state champion in “run-and-gun,” the format that rewards hunters and dogs for bagging a fixed number of upland birds, typically pheasants, in the least time with the fewest shells. While my opinion of these competitions is unprintable, the dogs have to be pretty darn good.

For Ashford’s part, Feather came into her life as everything she didn’t want. There are rumors that her decision to buy Feather may have been influenced by one too many Old-Fashioneds (the Wisconsin cocktail), but you didn’t hear that from me.

“She was yellow, she was a she, and she came from field stock,” Ashford says in her voluble, animated way. “This was a total departure from anything I’d ever owned, and she and I had a hard time connecting for the first few months. We didn’t like each other, I think because we’re both very ‘alpha’ personalities.

“We finally bonded when Feather was about four months old, and after that she just became so much fun to work with. She has a great attitude, she has all the desire you could ever want, she has a lot of trainability, and I love her enthusiasm. You get her out in the field and she’s all business. All heart, too.”

Ashford is quick to credit Roger Hanson, a retired Wisconsin conservation warden turned professional trainer, for his role in Feather’s development. One or both of them frequently make appearances with Feather at programs for at-risk or special needs kids, with Feather serving as an object lesson in the art of accepting a disability without letting it become a disability — and in achieving the goals you’ve set for yourself, even when the rest of the world tries to tell you they’re unattainable.

Not that you have to be a kid to appreciate that lesson — or to be inspired by Feather’s example. That’s the thing about dogs: they don’t stew over what might have been; they don’t eat themselves up with bitterness because they got the short end of the stick.

They’re just grateful they have a stick.

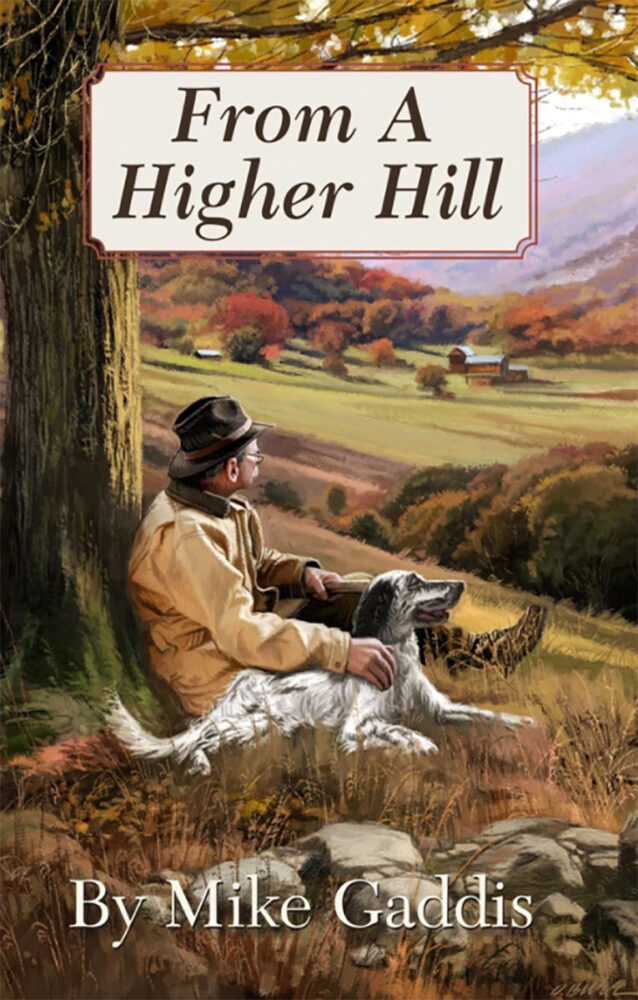

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now