Just because NASA is no longer sending manned shuttles into space doesn’t mean its technology is going to waste. Two satellites were recently tasked with a very important mission, although their goal wasn’t out among the stars.

The Terra and Aqua probes were used to locate areas a mule deer doe would likely bed down and give birth to her fawns. Using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, a measure of how a plant absorbs and reflects light back, analysts were able to pinpoint areas of lush herbage. These sites were deemed the most suitable for birthing.

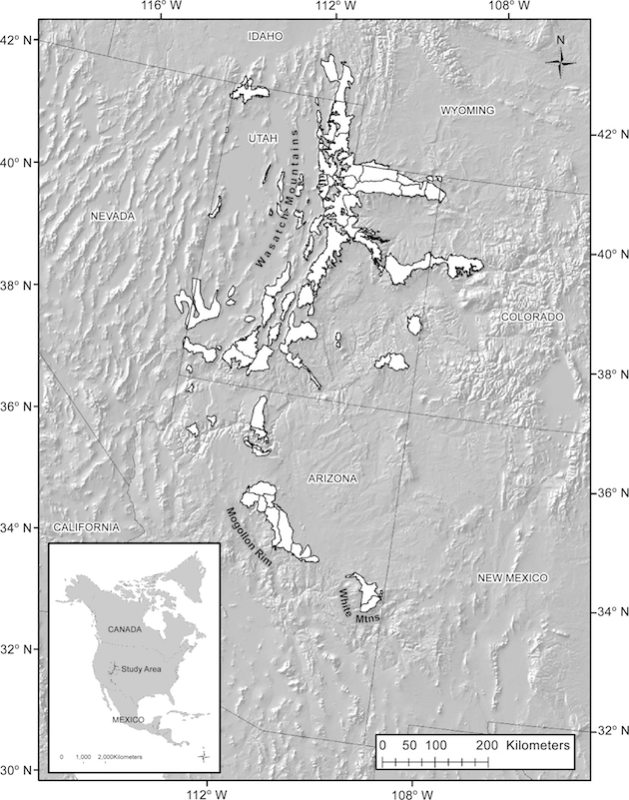

The satellites tracked three zones in the American Southwest for a full calendar year. Portions of Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Colorado, Wyoming, and Arizona were all analyzed, each composing a key portion of mule deer habitat.

The data pointed to a later green-up in southern latitudes versus northern ones, due to the southern areas’ reliance on summer rainfall and, presumably, northern ones on snowmelt.

Consequently, mule deer give birth earlier in the year northern latitudes and later in southern reaches. As a result, mule deer recruitment was higher in the northern areas.

The determinations will help researchers protect key areas of mule deer habitat. Mulies are struggling across their entire range, decreasing in numbers as other big games species are on the increase. Biologists previously believed lower ranges, the first to thaw out each spring, were the better areas to protect for mule deer conservation. NASA’s satellites have corrected that thinking and could help in the future with other habitat management efforts.

The complete findings were published in the scientific article “Ungulate Reproductive Parameters Track Satellite Observations of Plant Phenology across Latitude and Climatological Regimes” in PLOS (Public Library of Science) One.