Everyone should have an old man. I’ve got one; he’s in his 80s, and he lives on a ranch on a wide, sage-studded plain surrounded by mountains.

How about your old man?

Maybe he stokes a morning fire in a gray clapboard house along the Chesapeake. Down there the land meets the ocean in furtive, tide-washed coves, where strings of pintails and gadwalls and teal explore from the ditch grass, their bellies dripping with sparkling, sun-catching water.

Or maybe your old man has a place up in Michigan. A small house, only a five-minute walk from grouse cover, and six dog pens out back. Five of the pens are empty; in the sixth is an old setter bitch who gets to sleep inside on the coldest nights—they come more and more often these days—and who still gets fire in her eyes when your old man puts on his gun vest.

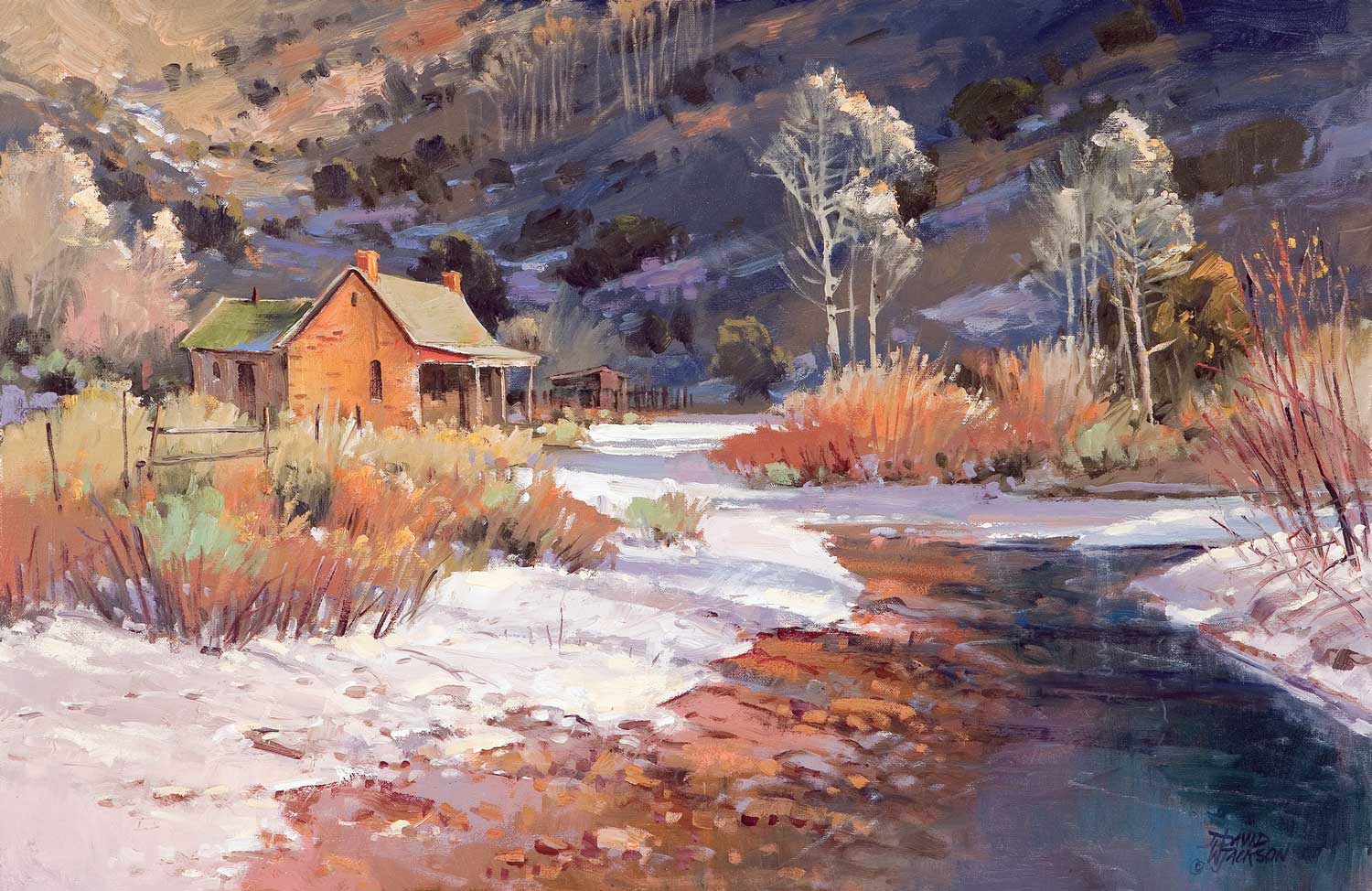

Alton, Utah by David Jackson

Or maybe Kansas. Green and wide and cut with brushy ravines. Maybe your old man was born there and has always lived there, except when he was overseas that time so many years ago (the last war humanity would ever have to fight, they said); maybe your old man lives in a small house under cottonwoods beside a slow, ox-bowing creek. Where meadowlarks go up like quail all along the wagon road, and where quail go up like nobody’s business when he motions you in on that staunch young pointer he’s been working.

Or maybe he lives Upstate. On the Pike. Where autumn mountains are red and brown, steep and rugged, cloaked with morning fog. Where deer eat windfall apples under a tree in the back yard (you daren’t shoot these deer, or even joke about it), and where you get up in the dark, hear the old man coughing in the kitchen, go out and see the pink wash in the east, walk with your old man as far as his stand, and then go up on the mountain to yours.

Maybe your old man has eyes pale as denim that’s been washed a hundred times. Or brown, sharp eyes sunk in a thicket of wrinkles. Maybe his hands are spotted and rough like buttonwood bark, his face weathered like a walnut hull that has lain all winter beneath the tree. Just below the cuffs, his wrists may be brown as elk antlers after the bulls have rubbed them against pine. Rain, wind, snow, sun, blurring, ticking heat, quiet cold—all robbed his skin of youth, beat it to toughness, browned and chafed and cracked it.

Maybe your old man wears Western boots, with a special, hand-made pair for shopping for livestock or going to town for the mail. Or arctics, with at least one broken buckle. Or leather-top rubbers bought from the same mail-order outfit year after year. Or birdshooter’s specials, with laces knotted where they’ve busted. Or maybe patched, re-patched, and finally electrician-taped waders.

Hat? Usually. Stetson: rippled, salt seeping from the band, grimy where thumb and forefinger tug the brim toward the eyes. Canvas dusk cap: tan or camouflage, faded and shapeless, but guaranteed to keep off spray and hide the face from incomers. Wool cap: black-and–red checked Richie, visor broken, threads raveling at the back, crazy little back button gone off the top.

What does he shoot if he still shoots? A Model 12 with an action that clatters like a sack of clams? A 35 Remington with a spiral magazine and a kick that’ll set you down if you aren’t ready? A .30-30 carbine with a triple circle of wire replacing the saddle loop? A Damascus steel double (“English, I don’t know the make, that’s wore off; it was Dad’s; we cut the stock down to fit me, and somewhere along the way Uncle Jack added a recoil pad and took a couple of inches off the barrels, which was a shame, ’cause it took off the little pearl they had up front for a sight; I think it’s out in the garage somewhere; want to see it?”).

The old man will show you the pearl.

He’ll show you many things. Like how to skin a squirrel quickly and efficiently and not get any fur on the meat. Or how to lace your boots so they won’t keep coming undone and slowing you down in woodcock cover. Or where to hunt turkeys during the last hours of a late-season day. Or where the elk lay up when the wind changes and snow begins to whip out of the east.

He’ll show you all these, plus many things less practical and more important. He may even show you yourself in 30 or 40 or 50 years.

You’re lucky if you have an old man. You’re doubly lucky if your old man still has the agility and desire to hunt. And you’re lucky beyond estimation if your old man is your father or grandfather.

I have an old man—no blood relation, but as fine an old man as one could hope for. I write to him every month or so, and wish I lived closer so I could drop by and see him more often.

My old man lives in Wyoming, on a ranch he bought about 15 years ago, before he became my old man. Before that, he and his wife worked a homestead high in the Sunlight Basin of the Absaroka Mountains. But the winters are long up in Sunlight—snow flies in October and the melt doesn’t come until late May—and they were getting old even then, so they bought a place down on the plain.

Pole Canyon by David Jackson

My old man’s wife is gone now. He ranches a little, with the help of a couple of friends and the day-to–day ease of habit. I met him through my aunt and uncle, who owned a neighboring ranch. Their place had bad water—alkaline, no good to drink—and every few days I would throw a half-dozen plastic bleach containers in the back of the car, and drive over to the old man’s place, and fill them from his well.

I can close my eyes and see the kitchen. Slick tablecloth, checkered dish towel draped over salt and pepper shakers, sourdough crock on the counter, stockman’s calendar on the wall, denim jacket hung over a chair back, crumpled tan Stetson on the seat, mud-flecked boots under it. Half an inch of dead flies in the well of a storm window, and out that window the bulk of Heart Mountain—sere or snow—dusted, dawn-rosy or gray as lead when the days shut down.

I have, over the last five years, spent a fair share of time in that kitchen. My old man tells me that “the latch string is out,” which means I may come any time and stay as long as I want.

After meals, my old man washes the dishes carefully, refusing my offer to perform this chore, and stacks them in a metal rack. Often the radio is on, soft but distinct, with “news of Cody and the Bighorn Basin.”

My old man sits back down, and we talk. We talk about things we don’t like, and the things we do, and my old man has plenty of both. He dislikes snowmobiles, the Forest Service (passionately), Charlais cattle, magpies, people who drive across his land and cut his fences, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and the whole idea of Coca-Cola. He likes a far greater number of things, including Chevrolet pickup trucks, Pendleton shirts, cats, jackrabbits, Hereford cattle, horses (he remembers some he owned 40 years ago and still grieves for them at times), people who show spirit and dignity under difficult conditions, Indians, neighbors, and certain memories.

Most of the memories have to do with hunting.

Like the time a bunch of hunters straggled into his cabin up in Sunlight, half-frozen after getting caught in a blizzard. They told him they’d lost a .30-30 saddle gun on the summit of the conical, nameless mountain that towers up on the edge of his homestead, and that he could have the rifle if he wanted to fetch it. He found it the following spring and used it over the decades to take a tremendous number and variety of game.

There was a bighorn killed right at timberline after a long stalk: the sheep all belting past through the talus, my old man’s rifle swinging on the biggest, the heavy sound of the bullet striking, the spasmodic kicking of the dead ram.

The moose he woke up to find browsing alder shoots 50 yards from the cabin: the bead front sight silver against the moose’s black side, the shot waking up my old man’s wife, the moose running a few steps toward the springhouse before falling.

The elk: so many he’s lost count. Elk taken for their racks, elk bugled in for friends, crippled elk finished off for hunters he was guiding. Depression elk—hillside salmon, government beef—one way to stay solvent when times were hard.

A grizzly taken in the day’s last light in a high-country meadow: the first shot breaking the animal’s jaw, its outraged bellow echoing from mountains and banks of shadowy pines, the second shot anchoring the bear, the third shot finishing it.

Or the time my old man was guiding, and they spooked a very ordinary mule deer buck out of a blowdown. They already had camp meat and a full packload, but the client wanted the deer, which stood on the edge of the trees watching them. The hunter asked for my old man’s .30-30 and was reluctantly given the gun. He worked a shell into the chamber, and in so doing, sandwiched the sling between the lever and stock, preventing the action from locking. The hunter squeezed the trigger. Nothing. He yanked it. My old man waited until the buck faded into the timber. Then he took the rifle back, saying, “You have to pull right hard.”

My old man talks about hunting and game and the way things were then and the way they are now, and I listen.

I sit across the table from him. The dawn lights his face, or the warm evening light filters into the room from where the sun is setting behind Elkhorn Peak up in Sunlight. My old man talks, and I listen, even though I’ve heard the stories before. If he knows he repeats himself, I hope he also knows I want to hear.

Note: Selected from The Wingless Crow, published in 2008 by the Penn State University Press.