Drive north from Jackson on Highway 89, into the heart of the National Elk Refuge. If you’re alert, if you know it’s there and you’re looking for it, you might see the museum. On the other hand, you might not, and that’s intentional.

When my father was stationed in Germany, he took us all to Lascaux, France, to see the famed, prehistoric paintings just before the cave was closed to the public. My sister recently recalled the cave as “a holy place, where the magnificent creatures painted on the walls eclipsed any other portion of the experience. The paintings seemed alive, just temporarily unmoving, and there was a power in the art that I could not explain. I knew some type of magic outside my experience was at work, and I couldn’t, nor did I try to, explain what its meaning was.”

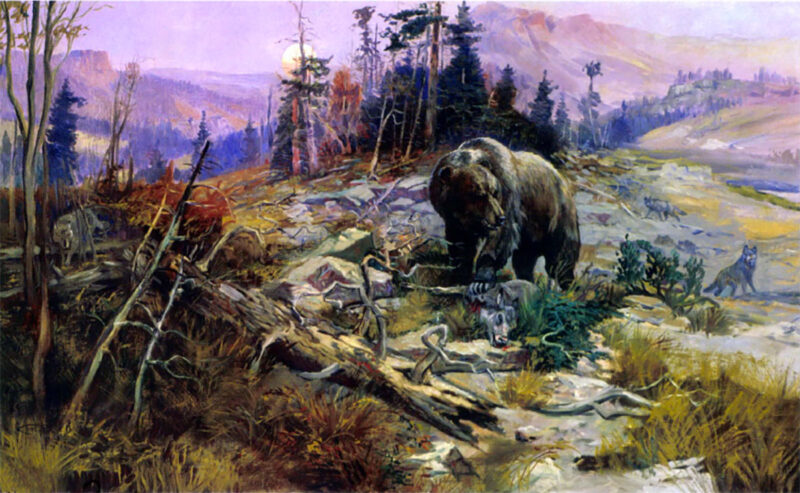

To The Victor Belongs The Spoils by Charles Marion Russel – JKM Collection

A quarter-century later, in Namibia, the owner of a game ranch gave me a map to a hidden cave on her property where there were prehistoric paintings that dated back about 10,000 years, roughly half the age of those at Lascaux. This was before I had ever read Peter Hathaway Capstick’s excellent advice about never going for a walk in Africa without a firearm, and I very nearly became yet another news item about African-tourist naivete. But what struck me then, and what stays with me now, apart from the sheer, staggering power of that art, is how two completely different peoples, different races, different cultures, in greatly different eras, and on very different continents could be linked by their common fascination with and reverence for animals, and especially by their artistic sensibility.

Equally interesting is to think that modem man (at least those who have a reality apart from smartphones and shopping malls) shares that fascination. Our artistic sensibility may have changed — for the better or for the worse, depending on your point of view and what painting you’re looking at — but the fascination and the reverence remain.

Pas De Deux by Robert Kuhn – JKM Collection

Jackson Hole. It’s one of those storied international playgrounds for the very wealthy — a western version of Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat or St. Moritz, or one of those private islands in the Caribbean, the kind of place where if you have to ask how much a house costs, you can’t afford it. It’s the kind of place where those unaffordable houses are not second or even third homes, but usually fifth or sixth or seventh homes used only for a month or two in the summer, a few weeks during ski season; private jets and Dom Perignon mingling with Wrangler jeans and Lucchese boots and 1000X Stetsons.

Wounded Comrade by Carl Ethan Akeley – Gift of the 1999 Collector’s Circle

Like all watering holes for the wealthy, Jackson Hole is a reflection of its times, and that being the case, “the times they are a’ changin’” for the better. Less than a hundred years ago, the town of Jackson was — in the words of a lady who hunted there — “a dusty frontier town consisting of a post office and a couple of houses.” It has managed to come a long way without being destroyed by too much progress, transformed and preserved by men and women who fell in love with some of the purest and most breathtaking beauty to be found anywhere in the world. It is no accident that Academy Award-winning director George Stevens picked Jackson Hole as the location for his classic western, Shane. The setting has been described by more than one critic as one of the primary stars of that film, and is part of the reason why it won its sole Oscar for its cinematography.

The town of Jackson and the valley in which it sits are named after an early mountain man, fur trapper and explorer named David Edward Jackson, who is also remembered for being Stonewall Jackson’s uncle. Jackson is the gateway to both Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, as well as being home to the National Elk Refuge. The headwaters of the Snake River is in Teton County, so there is excellent fly fishing, kayaking and whitewater rafting in addition to hiking, horseback riding, skiing and snowmobiling. And now, thanks to an extraordinary couple with extraordinary vision, Jackson is transforming itself from a hip-and-happening outdoor playground into a cultural mecca.

Like many others before them, William and Joffa Kerr fell in love with Jackson and Jackson Hole a long time ago. After generating a great deal of enthusiasm within the community, they attracted a dedicated group of founding trustees, who along with the Kerrs, saw an opportunity to transform the area into something quite unique. What they created was the Congressionally designated National Museum of Wildlife Art of the United States.

Life Imitates Art by Len Chmeil – Gift of the 2002 Collector’s Circle

Drive north from Jackson on Highway 89, into the heart of the National Elk Refuge. If you’re alert, if you know it’s there and you’re looking for it, you might see the museum. On the other hand, you might not, and that’s intentional. Built into the side of a hill, and built out of the same native rock that lies exposed around that part of Wyoming, the most obvious thing you will see is the American flag. The museum itself takes its inspiration from the ruins of Slains Castle in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, an inspiration that was the brainchild of Joffa Kerr. What the Kerrs wanted, and what they achieved, was a spacious museum that would blend into the landscape so completely it is almost indiscernible; after all, in Jackson Hole, it is the land that is the star attraction.

Eland by Rembrandt Bugatti – JKM Collection

In many of the great cities of the world, museums are historic buildings of fabled beauty and antiquity: think of the Louvre in Paris; the Uffizi in Florence; the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. In other, more modem instances, the museum itself was built as a work of art to house works of art. Probably the two most notable examples are the Guggenheim in New York and the Getty in Los Angeles; both are places where the building itself delights the eye and pleases the soul as much as the art. And now, in that second category, there is the National Museum of Wildlife Art.

The architecture of the building is beautiful and unobtrusive from the outside, while from the inside it encourages your attention to the breathtaking beauty of Jackson Hole and the Elk Refuge. There is an exterior sculpture walk, where a winding path along the hillside takes you from masterpiece to masterpiece with all of the valley and surrounding mountains as backdrop.

Pine Martin Attacking Cock Capercaillie by Bruno Liljefors – Gift from the 2003 Collector’s Circle.

Once inside, walls of glass bring that outside in, all of the famed valley and the surrounding mountains, including one of God’s more whimsical sculptures, the Sleeping Indian Mountain. If someone took every single painting and piece of sculpture out of the museum, it would still be worth a visit.

Fortunately, no one has done that.

The strength of a museum, of any museum, lies in the depth of its collection. At any given time, the art that hangs on the walls for the public to see represents only a fraction of a museum’s total collection, but in the normal course of events it takes many, many years, even centuries, for a museum to build up that kind of depth. Money is raised to purchase specific works of art if and when they come on the market; people with more or less appropriate pieces donates some or all of their collections for charitable or tax or other purposes; serious collectors die and will their lives’ work to the museum of their choice. But such things normally take many decades.

Fighting Stags By Moonlight by Georges-Frederic Rotig – JKM Collection

The National Museum of Wildlife Art was fortunate enough to have an extraordinary private collection to start with, courtesy of Bill and Joffa Kerr, who donated 250 paintings to jumpstart the museum. That collection constitutes the backbone — if you will — of the museum, and consists of the nation’s largest public congeries of Carl Rungius, considered by many to be the greatest painter of North American wildlife.

That may be, but Rungius did not spring fully grown out of the rocky soil of the American West. Born and trained in Germany, he himself acknowledged fellow German painter Richard Friese as one of his primary sources of inspiration and motivation, and Friese was only one of several European musts who emerged contemporaneously, including Wilhelm Kuhnert, Bruno Liljefors, Arthur Wardle, Edwin Landseer and others who raised “wildlife art” from something thought of as illustration to art that stands on its own as a reflection of the time and place in which it was created.

All art reflects its era of creation, and much of the early history of wildlife art is a record of exploration, a categorizing and cataloguing of the new and unfamiliar; think of the Audubons, père et fils, or the work of Mark Catesby or George Catlin. The quality of the art may vary by the skill of the artist, but the intent was the same: to provide an illustration of the unknown. It was men like Rungius and his contemporaries, and women like Rosa Bonheur, who elevated the subject from an object of curiosity unto itself into both a symbol and a reflection of the larger world.

The Struggle for Existence by William Robinson Leigh – Peter A. Juley and Son, Photographers, National Museum of Fine Art.

An obvious example of wildlife art as a mirror of time and place would be American-born Newbold Trotter’s Domain Invaded. Superficially, it appears to be nothing more than a study of a herd of elk on a rocky outcropping. It’s only when you look closely that you realize the painting is done, uniquely, from the elk’s point of view, and that the herd is looking at a distant campfire. It was painted in 1870, when the vast American wilderness was considered to have been finally and fully explored.

Stretching Tiger by Johnathan Kenworthy

The museum’s range, from primitive, Native American “birdstones,” to the work of such modem giants as Bob Kuhn, Tom Quinn, Andy Warhol, Lanford Monroe, Georgia O’Keefe and so many more, provides a panorama of how man views his fellow travelers on this weary earth. And that is the great strength and joy of the National Museum of Wildlife Art: it gives the visitor a spectrum of the best of the best, drawing on both primitive and European antecedents to provide a sense of the wonder man still feels about the world around him, linking him to those long-vanished artists from Lascaux and Namibia and elsewhere, encouraging the same fascination and reverence of his ancestors, the same sense of the holy. The millennia and the continents are different, but man endures. Nothing has changed, nothing has changed.

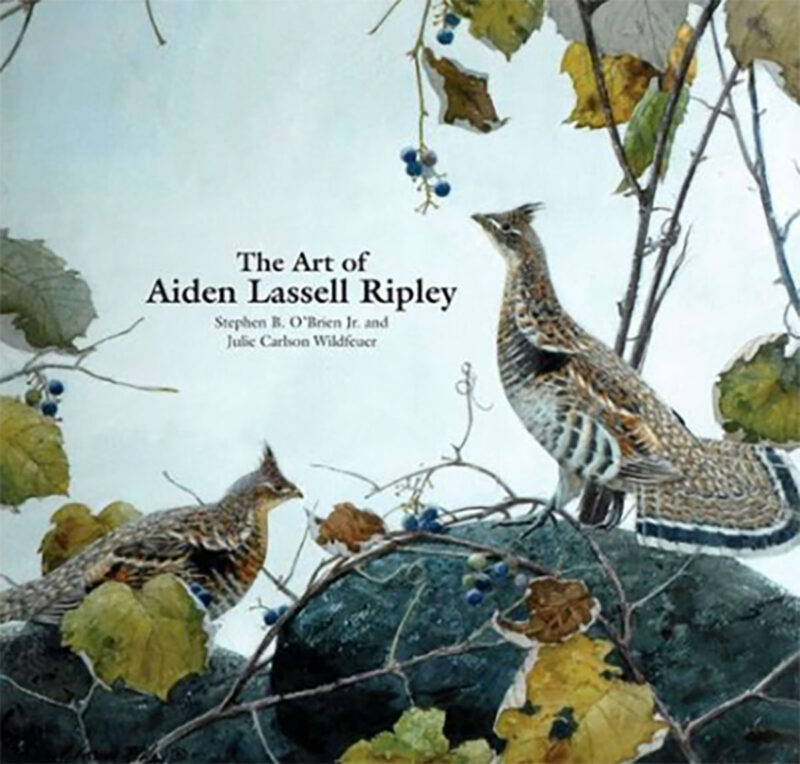

The Art of Aiden Lissdell Ripley is the most comprehensive book to date on the artist chronicling paintings from his early life and work, illustrations and murals, landscapes and cityscapes, scenes of the south and his well known sporting art.

The Art of Aiden Lissdell Ripley is the most comprehensive book to date on the artist chronicling paintings from his early life and work, illustrations and murals, landscapes and cityscapes, scenes of the south and his well known sporting art.

Through numerous illustrations, this full-sized 11 x 12 inch book documents the artist’s progression and growth, from his early award-winning and acclaimed rise as an Impressionist to his accurate and detailed depictions that continue to shape sporting art today. Buy Now