“If fishing interferes with your business, give up your business,” any angler will tell you, citing instances of men who have lost health and even life through failure to take a little recreation, and reminding you that “the trout do not rise in Greenwood Cemetery,” so you had better do your fishing while you are still able. But you will search far to find a fisherman to admit that a taste for fishing, like a taste for liquor, must be governed lest it comes to possess its possessor; that an excess of fishing can cause as many tragedies of lost purpose, earning power and position as an excess of liquor.

This is the story of a man who finally decided between his business and his fishing, and of how his decision was brought about by the murder of a trout.

Fishing was not a pastime with my friend John but an obsession – a common condition, for typically your successful fisherman is not really enjoying a recreation, but rather taking refuge from the realities of life in an absorbing fantasy in which he grimly if subconsciously re-enacts in miniature the unceasing struggle of primitive man for existence. Indeed, it is that which makes him successful, for it gives him that last measure of fierce concentration, that final moment of unyielding patience, which in angling so often make the difference between fish and no fish.

John was that kind of fisherman, more so than any other I ever knew. Waking or sleeping, his mind ran constantly on the trout and its taking, and back in the Depression years, I often wondered whether he could keep on indefinitely doing business with the surface of his mind and fishing with the rest of his mental processes – wondered, and feared that he could not.

So when he called me one spring day and said, “I’m tired of sitting here and watching a corporation die; let’s go fishing,” I know that he was not discouraged with his business so much as he was impatient with its restraint. But I went with him, for maybe I’m obsessed myself.

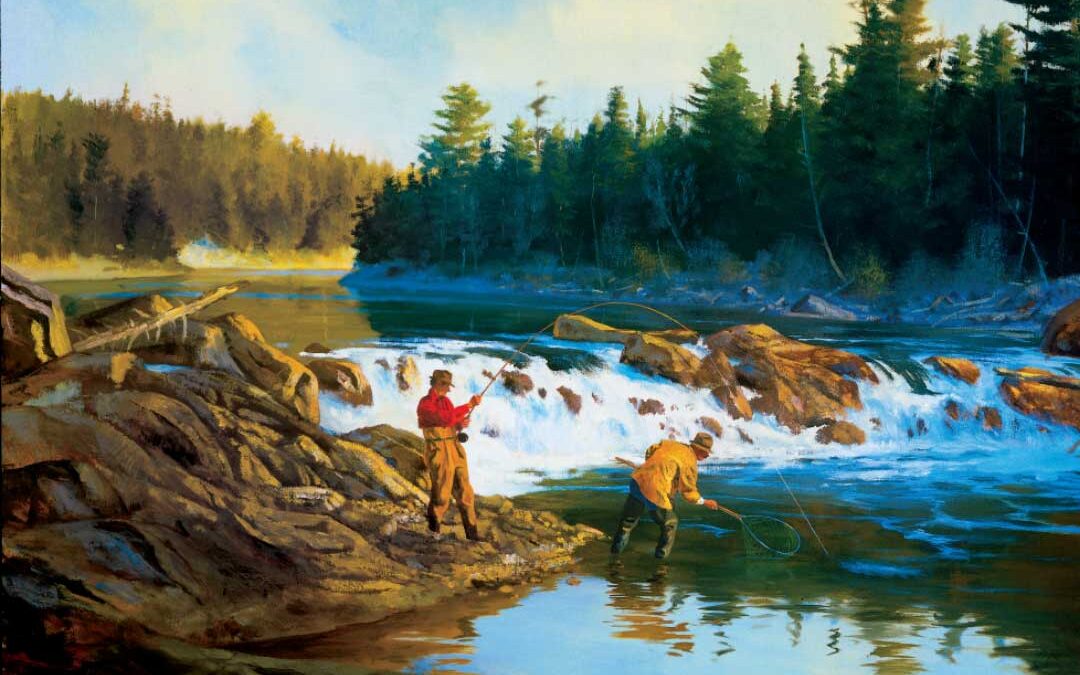

Waterfall Pool by Brett James Smith

That day together on the river was like a thousand other pages from the book of any angler’s memories. There was the clasp and pull of cold, hurrying water on our legs, the hours of rhythmic casting, and the steady somnambulistic shuffling which characterizes steelworkers aloft and fly fishermen in fast water. Occasionally our heads were bent together over a fly box; at intervals our pipes wreathed smoke, and from time to time a brief remark broke the silence. We were fishing “pool and pool” together, each as he finished walking around the other to a new spot above him.

Late afternoon found me in the second pool below the dam, throwing a long line up the still water. There was a fish rising to some insect so small that I could not detect it, so I was using a tiny gray fly on a long leader with a 5x point. John came by and went up to the dam pool and I lost interest in my refractory fish and walked up to watch, for there was always a chance of a good fish there.

I stopped at a safe distance and sat down on a rock with my leader trailing to keep it wet, while John systematically covered the tail of the pool until he was satisfied that there were no fish there to dart ahead and give the alarm, and then stepped into it.

As he did so his body became tense, his posture that of a man who stalks his enemy. With aching slowness and infinite craft he began to inch up the pool and as he went, his knees bent more and more until he was crouching. Finally, with his rod low to the water and one hand supporting himself on the bottom of the stream, he crept to a casting position and knelt in mid-current with water lapping under his elbows, his left sleeve dripping unheeded as he allowed the current to straighten his line behind him. I saw that he was using the same leader as mine but with a large No. 12 fly.

“John, using 5x?” I breathed. Without turning his head he nodded almost imperceptibly.

“Better break off and reknot,” I counseled softly, but he ignored the suggestion. I spoke from experience. Drawn 5x gut is almost as fine as a human hair, and we both knew that it chafes easily where it is tied to a fly as heavy as No. 12, so that it is necessary to make the fastening in a different spot at frequent intervals in order to avoid breaking it.

I kept silence and watched John. With his rod almost parallel to the water he picked up his fly from behind him with a light twitch and then false-cast to dry it. He was a good caster; it neither touched the surface nor rose far above it as he whipped it back and forth.

Now he began lengthening his line until finally, at the end of each forward cast, his fly hovered for an instant above a miniature eddy between the main current and a hand’s breadth of still water which clung to the bank. And then I noticed what he had seen when he entered the pool – the sudden, slight dimple denoting the feeding of a big fish on the surface.

The line came back with a subtle change from the wide-sweeping false casts, straightened with decision and swept forward in a tight roll. It straightened again and then checked suddenly. The fly swept round as a little elbow formed in the leader, and settled on the rim of the eddy with a loop of slack upstream of it. It started to circle, then disappeared in a sudden dimple, and I could hear a faint sucking sound.

It seemed as if John would never strike, although his pause must have been but momentary. Then his long line tightened – he had out 50 feet – as he drew it back with his left hand and gently raised the rod tip with his right. There was slight pause and then the line began to run out slowly.

Rigid as a statue, with the water piling a little wave against the brown waders at his waist, he continued to kneel there while the yellow line slid almost unchecked through his left hand. His lips moved.

“A big one,” he murmured. “The leader will hold him if he gets started. I should have changed it.”

The tip of the upright rod remained slightly bent as the fish moved into the circling currents created by the spillway at the right side of the dam. John took line gently and the rod maintained its bend.

Now the fish was under the spillway and must have dived down with the descending stream, for I saw a couple of feet of line slide suddenly through John’s hand. The circling water got its impetus here and this was naturally the fastest part of the eddy.

The fish came rapidly toward us, riding with the quickened water, and John retrieved the line. Would the fish follow the current around again, or would it leave it and run down past us?

The resilient rod tip straightened as the pressure was eased. The big trout passed along the downstream edge of the eddy and swung over the bank to follow it round again, repeated its performance at the spillway, and again refused to leave the eddy. It was troubled and perplexed by the strange hampering of its progress, but it was not alarmed, for it was not aware of our presence or even of the fact that it was hooked, and the restraint on it had not been enough to arouse its full resistance.

Every experienced angler will understand that last statement. The pull of a gamefish, up to the full limit of its strength, seems to be in proportion to the resistance which it encounters. As I watched the leader slowly cutting the water, I recalled that often I had hooked a trout and immediately given slack, whereupon invariably it had moved quietly and aimlessly about, soon coming to rest as if it had no realization that it was hooked.

I realized now that John intended to get the “fight” out of his fish at a rate slow enough not to endanger his leader. His task was to keep from arousing the fish to a resistance greater than the presumably weakened 5x gut could withstand. It seemed as if it were hopeless, for the big trout continued to circle the eddy, swimming deep and strongly against the rod’s light tension, which relaxed only when the fish passed the gateway of the stream below. Around and around it went, and then at last it left the eddy. Yet it did not dart into the outflowing current, but headed into deep water close to the far bank.

I held my breath, for over there was a tangle of roots, and I could imagine what a labyrinth they must make under the surface. Ah, it was moving toward the roots! Now what would John do – hold the fish hard and break off; check it and arouse its fury; or perhaps splash a stone in front of it to turn it back?

He did none of these but instead slackened off until his line sagged in a catenary curve. The fish kept on, and I could see the leader draw on the surface as it swam into the mass of roots. Now John dropped his rod flat to the water and delicately drew on the line until the tip barely flexed, moving it almost imperceptibly several times to feel whether his leader had fouled on a root. Then he lapsed into immobility.

I glanced at my wristwatch, slowly bent my head until I could light my cold pipe without raising my hand, and then relaxed on my rock. The smoke drifted lazily upstream, the separate puffs merging into a thin haze, which dissipated itself imperceptibly. A bird moved on the bank. But the only really living thing was the stream, which rippled a bit as it divided around John’s body and continually moved a loop of his yellow line in the disturbed current below him.

When the trout finally swam quietly back out of the roots, my watch showed that it had been there almost an hour and a quarter.

John slackened the line and released a breath, which he seemed to have been holding all that while, and the fish re-entered the eddy to resume its interminable circling. The sun, which had been in my face, dropped behind a tree, and I noted how the shadows had lengthened. Then the big fish showed itself for the first time, its huge dorsal fin appearing as it rose toward the surface and the lobe of its great tail as it turned down again; it seemed to be two feet long.

Again its tail swirled under the surface, puddling the water as it swam slowly and deliberately, and then I thought that we would lose the fish, for as it came around to the downstream side of the eddy, it wallowed an instant and then headed toward us. Instantly John relaxed the rod until the line hung limp and from the side of his mouth he hissed, “Steady!”

Down the stream, passing John so closely that he could have hit it with his tip, drifted a long dark bulk, oaring along deliberately with its powerful tail in the smooth current. I could see the gray fly in the corner of its mouth and the leader hanging in a curve under its belly, then the yellow line floating behind. In a moment he felt the fish again, determined that it was no longer moving, and resumed his light pressure, causing it to swim around aimlessly in the still water below us.

The sun was half below the horizon now and the shadows slanting down over the river covered us. In the cool, diffused light the lines on John’s face from nostril to mouth were deeply cut and the crafty folds at the outer corners of his lids hooded his eyes. His rod hand shook with a fine tremor.

The fish broke, wallowing, but John instantly dropped his rod flat to the water and slipped a little line. The fish wallowed again, then swam more slowly in a large circle. It was moving just under the surface now, its mouth open and its back breaking water every few feet, and it seemed to be half turned on its side. Still, John did not move except for the small gestures of taking or giving line, raising or lowering his rod tip.

Trail Creek Meadow by Brett James Smith

It was in the ruddy afterglow that the fish finally came to the top, beating its tail in a subdued rhythm. Bent double, I crept ashore and then ran through the brush to the edge of the still water downstream of the fish, which now was broad on its side. Stretching myself prone on the bank, I extended my net at arm’s length and held it flat on the bottom in a foot of water.

John began to slip out line slowly, the now beaten trout moving feebly as the slow current carried it down. Now it was opposite me and I nodded a signal to John. He moved his tip toward my bank and cautiously checked the line. The current swung the trout toward me and it passed over my net.

I raised the rim quietly and slowly and the next instant the trout was doubled up in my deep-bellied net and I was holding the top shut with both hands while the fish, galvanized into a furious flurry, splashed water in my face as I strove to get my feet under me.

John picked his way slowly down the still water, reeling up as he came, stumbling and slipping on the stones like an utterly weary man. I killed the trout with my pliers and laid it on the grass as he came up beside me and stood watching it with bent head and sagging shoulders for a long while.

“To die like that!” he said, as if thinking aloud. “Murdered – nagged to death; he never knew he was fighting for his life until he was in the net. He had strength and courage enough to beat the pair of us, but we robbed him a little at a time until we got him where we wanted him. And then knocked him on the head. I wish you had let him go.”

The twilight fishing, our favorite time, was upon us, but he started for the car and I did not demur. We began to take off our wet shoes and waders.

“That’s just what this depression is doing to me!” John burst out suddenly as he struggled with a shoelace. “Niggling me to death! And I’m up here fishing, taking two days off in the middle of the week, instead of doing something about it.

“Come on; hurry up. I’m going to catch the midnight to Pittsburgh; I know where I can get a contract.”

And sure enough, he did.

Note: Alfred W. Miller took up the non de plume Sparse Grey Hackle during the 1930s and ’40s when he was writing articles and columns about fishing on his beloved Catskill streams. “Murder” was among a collection of his most popular stories in Fishless Days, Angling Nights, first published in 1971 by Crown Publishers in New York. “Murder” is reproduced by permission of Skyhorse Publishing Inc. and is © 1971, 2011, The Estate of Alfred W. Miller.