From the November/December 2014 issue of Sporting Classics.

It’s the kind of thing that makes the world beat a path to your door and then kick it down if you don’t answer at first knock. To pin the point like a shrike, it’s a special mule deer permit covering a swath of northern Idaho that opens in late August when the bucks are bachelored in the high country and hard-antlered under velvet.

To be fair, whosoever finds their name engraved on this magical piece of paper can opt for whitetail in the valleys, but that would be a blasphemy of highest order. Best use involves a packstring, fly camp, and a flat-shooting rifle akin to a sheep hunt.

Each year Idaho Fish and Game issues about 50 of these special opportunities via drawing. Odds of success are predictably discouraging, on par with pulling for bighorn or winning the heart of Miss America. There is, however, another way. A single permit is available through the outfitter who has long operated in much of this country—Bruce Duncan of Selkirk Guiding and Outfitting. I’ve known Bruce for better than 30 years and have hunted with him for black bear, bobcat, and cougar. We’re proper friends too, but even though I’ve been lobbying hard for his deer permit from the instant I learned of it long ago, it finally came my way only because others in the long line ahead of me turned it down because of short notice.

I excused myself to call home so Kellie could verify my life insurance premium was up to date.

“You still want that deer permit? Season opens in six days, and the hunter just called off. If you do, I’ll ask fish and game to get it transferred.”

I blurted a response that eliminated any vestige of doubt regarding my interest.

“OK, but are you in shape for this?”

I then related how I was indeed in good shape for a man of my demographic profile and one not overly concerned with the future given the sorry state of world affairs.

“That’s what I thought,” Bruce deadpanned. “Better torture yourself now and make what progress you can. We’re going to the top and it’s awful steep up there.”

I should have paid more mind to the “awful steep” part of Bruce’s description, but brushed it aside by asking when he wanted me to turn up at his lodge.

I stiff-armed projects from my desk as only the irresponsibly self-employed can, canceled appointments and rescheduled a brace of trips in case things took longer than anticipated. My most wonderful and perfect dog, Mr. Jed, followed me to the garage and waited patiently while I loaded a backpack with several gallon jugs of water, grabbed a hiking staff and took off across the yard to a steep hill that tumbles to a lake. Jed followed me as I climbed up and down for a couple of 30-minute sessions that day, stuck with me during a pair of 45s the next and thereafter for an hour each morning and evening until it was time to drive to Idaho. I raided the medicine cabinet with scorched-earth intensity for painkillers and provided great amusement for my family by sweating like an army mule during each assault.

There was rifle-work to be done as well. I had just made ready for a leopard hunt, and my hyper-accurate Kimber .300 WSM was dead on for the expected 62-yard shot. Back to the range I went with a box of Federal Premium Trophy Copper 180-grainers. After settling the rifle in the bags and reversing the number of clicks I’d turned into the Leupold only days before, the usual three-inches-high zero came right back. Another three-shot group predictably confirmed things were as they should be, and once back home I cleaned and fouled the bore.

Following Bruce’s instructions to “just bring everything” for repacking at his lodge, I made the five-hour drive the morning before opening day. Bruce was unloading horses when my truck surfed across the thick gravel of his driveway and sunk to a stop. I immediately pitched in to help by staying well out of his way.

When it finally seemed safe to close the distance and exchange a customary greeting, I shook Bruce’s hand while asking if one of those things was intended for me.

“Only if you don’t want to walk,” came the flat reply. Being someone who approaches close contact with horses with the same degree of caution applied to red-haired women in my younger days, I then wondered out loud which one might be my intended conveyance.

“That one. Her name’s Jazz,” Bruce replied, jerking his head toward a dangerous looking mare with her head buried in a bucket of oats. “Hand me that blanket,” he then misdirected.

I’d have much preferred that her name be Pokey, but knew where we were headed and excused myself to call home so Kellie could verify my life insurance premium was up to date.

Guide Rick Johnson hauled up at about that time, and talk quickly settled on what scouting had turned up. Between them, Bruce and Rick had made eight trips, half of those after they determined where the hunt would concentrate. All in, they had seen 50 or 60 bucks, with seven or eight being what they called “contenders.” They even had grainy through-the-spotting-scope photos of some, but not the one that captured my attention from the instant he was described.

“He’s at least a main-frame four with a drop on one side—really more of a big club than a tine. He might have some trash too, but he was a couple miles away and almost at the top of the mountain. He was so high a pair of mountain goats were feeding below him in the next chute. A couple of baby bucks were following him around like he was the all-knowing king.”

“I know the type. Seen it in the business world,” I mumbled. “Guys selling short love them.”

“I think there’s at least four bucks on that mountain that’ll make you happy,” Bruce chimed, “but I suspect you’ll want to look for the drop tine.”

“That’s one of the many things I like about you,” I replied. “You’re a good guesser.”

Northern Idaho is usually dry in August, but this was a summer of rain. It had been nonstop wet since the middle of the month, and the sky was dark and threatening. We set about packing and had everything ready before dinner, a good thing since alarms were set for 2:45 the next morning. By the time the sun dropped, it was raining hard.

The next morning we drove to the trailhead, swapping hunting stories on the way, then with one horse packing and two saddled, we took up the trail at first light. Bruce wanted to hunt on our way in, at least casually, rather than just blowing through a bunch of good country. Long days meant there would still be plenty of time to get to where we wanted, throw up a camp and settle in behind some big glass before the bucks were due to feed into the open that evening.

I surrendered and let the image burn deeply into my memory, for it was one of the finest outdoor presentations I’d ever seen.

Three miles in, we came to a creek. Bruce led the packhorse across, Rick’s followed without incident, and my darling Jazz stopped for a drink. At least, that’s what I thought she was doing until she hurdled the water like one of those high-bred show horses at a jumping competition. Rick, having turned to give a warning, witnessed a spectacular display of horsemanship and somehow managed to keep a straight face.

“That’s one of her bad habits,” he said, then failed to respond to my immediate inquiry as to the others. Of course, he had already turned up the trail and kicked his horse into a trot in an effort to conceal his laughter.

We rolled on, stopping now and again to scan promising slopes. The sun was high by the time it punched through the clouds and not long after we bumped into the first good buck, a high-racked three-point that kept to his bed and watched us right back. He wasn’t overly wide, but made up for it in mass. Still wearing a velvet crown that fairly sparkled, the ruddy chestnut of his summer coat clashed with the brilliant green of the surrounding grass. I surrendered and let the image burn deeply into my memory, for it was one of the finest outdoor presentations I’d ever seen.

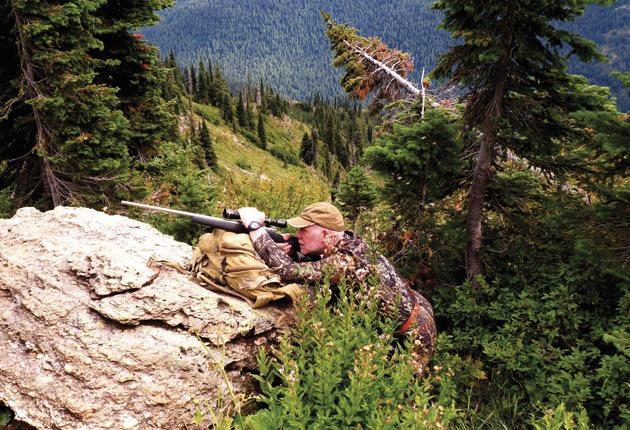

We tied up just past noon, pawed crushed lunches from saddlebags and pushed through a screen of trees to a big rock.

“He was over there,” Bruce whispered, “in that far clearing near the top. We were down there,” he added, pointing to a speck of a clearing across the drainage far below. The sun skittered behind another bank of clouds just as I started to look things over with binoculars.

“We’ll make a camp down the trail and then come back later this afternoon. I want to set up dry if possible.”

It took some doing to find a level spot near water, but we managed and then got things in an organized scatter. While Rick opted for a backpacking tent, Bruce preferred to sleep sandwiched between a ground cloth and a tarp stubbed off to some trees.

“I don’t like a tent in grizzly country. They’re up here, and I’ve had them come right up and sniff through the nylon. Never again.”

I threw my bag next to his, figuring the horses would give us plenty of warning if something was about to go bad. I’ve been grizzly-sniffed too, and agreed with Bruce that it does indeed gain your full attention.

The three of us were back on the glassing rock by late afternoon. The weather held for a bit, then it began to rain. We scanned the far slopes when it stopped and pulled back to cover when it squalled. All we had to show for it at dusk was some does and glimpses of little bucks. Rick kept us entertained with stories of midwestern whitetail hunting and Bruce pointed to landmarks where his hunters had taken great bucks in past years.

“We’ll be back here at first light and give it a couple of hours,” Bruce said quietly. “If nothing shows, we’ll work across the slope and through that far notch.”

Funny thing was, I didn’t think the landing would kill me, but figured it would probably break my neck or back.

From where we were sitting, the pitch of the slope looked manageable, and I wanted to look into the chutes where they had watched the big bucks while scouting. “Sounds good,” I offered.

It rained most of the night. We managed to keep dry, but the trail to the top had become a muddy path that demanded attention in the steeper stretches. Back at the rock, we waited for light and then began picking things apart. The odd deer appeared, most likely the same animals from the previous evening, so after a time Bruce thought we should start making our way across.

After just a few steps I knew things were going to get ugly. The slope was much steeper than I had realized, plus the ground was soaked and the brush was snot-slick. Although we are the same age, Bruce has always been able to walk me into the ground. Rick is much younger and went to college on scholarship as a decathlete. Where they walked, I struggled. Where they struggled, I crawled. I planted my rifle on the downhill side and clutched at whatever wisps of brush I could find above, and it still took me 30 minutes to make 150 yards. I could see Bruce moving up ahead but Rick was waiting, and the reason he was waiting was that things went from bad to worse.

A chunk of the slope had recently washed out, leaving a cut about four steps across with one miserable little bush in the middle holding on in desperation. Rick gave a pep talk, managed to cross and reached back for my rifle. I handed it over, reluctantly, then stepped out into space. My right foot just managed to reach the bush, but now I was splayed out like Spiderman and gripping the mountain with nowhere to go. I was pretty sure that I was going to fall. Funny thing was, I didn’t think the landing would kill me, but figured it would probably break my neck or back.

Rick worked ahead, found a place to lay my rifle and quickly returned, offering an outstretched hand. I finally convinced myself to let go and take it, but he pulled me across to where I could manage on my own. I glanced ahead, and from what I could see it was not going to get any better.

I was thanking Rick about the time Bruce returned, then I told them both that I couldn’t make it. Unless we could backtrack and find another way, I was done, no matter what deer might be waiting up ahead. Crossing that chute had left me badly shaken. I apologized for ruining the hunt and wasting their efforts. We sat quietly for a few minutes, for there was little left to say.

Bruce decided to go ahead and check the route, and within minutes Rick offered to carry my rifle if I wanted to give it another try. Maybe I’d calmed down enough to realize things weren’t as bad as they seemed, but for whatever reason I agreed.

When Bruce saw us up and moving he just kept going, and some time later we somehow made it out the far side of the canyon. Rick had found a walking stick for me along the way, which helped a great deal, but I never want to do anything like that again. Without their help and patience I would never have managed.

After we topped out, Bruce noticed that the sun was reflecting off something far below. It was a good buck but not one of the big boys, so we kept to the contour as soon as he drifted out of sight.

The slope remained terribly slick from the rains, but we were still-hunting so slowly it no longer mattered. Caught in the open, we froze when a doe appeared in the distance. She stared us down, then walked stiff-legged into a line of trees. We kept going, found a trail that seemed to lead in the direction Bruce wanted to go and took it. To me at least, the trail felt like a sidewalk.

We soon bumped another doe that went bounding away in that curious pogo-stick gait mule deer adopt when startled. After waiting to make sure she didn’t pick up some company, Bruce suggested we eat lunch and let things calm down. Not long after, Rick noticed a forkhorn feeding through the trees far above.

Alternately keeping track of the little buck and watching the surrounding country, I soon spotted a second deer, a spike, close by the first. Remembering Rick had said there were two little bucks with the dropper, I tried to get his attention, but by the time I did, the spike had disappeared.

Bruce came back from his vantage point about then and we filled him in together.

“That’s strange,” Bruce whispered. “Little bucks aren’t usually alone this time of year. Let’s wait here for a while.”

Wait we did, catching glimpses of deer moving back in the trees, mostly walking and once running, but after it had been quiet for a time we slung packs and started along the trail.

Bruce hadn’t gone a dozen steps before he stopped and turned to Rick.

“We’ll stay here. You go ahead to that ridge and then climb up to the level of the bucks. Move slowly and see if you can push them this way and into the open. Shouldn’t take but a few minutes.”

As Rick moved away, Bruce explained it bothered him that one of the bucks had been running. “He wasn’t running because we scared him, so he might have been pestering a big one.”

Mostly to humor, I placed my pack on a convenient rock and chambered a round. Bruce ranged the opening in the bench where the bucks had been feeding at just under 200 yards. We settled in quietly.

Rick later shared that he wanted to get beyond where we had last seen the deer before starting his climb and at the same time not expose himself to any that might be bedded in the next drainage. He kept to cover and, fortunately, found the wind was running in his favor.

Using a broken tree as a marker, he moved carefully until he gained the right elevation and then took the contour that would bring him out above where we were waiting. He hadn’t gone far when a big buck rose from his bed, not 30 yards away. Rick froze, off-balance and leaning hard on the walking stick he’d picked up and given to me earlier that morning, its jagged top digging deeply into his palm.

Rick and the deer stared each other down for at least 15 minutes, neither moving as much as a twitch. Finally satisfied, the deer turned away and lay back in his bed. Taking advantage, Rick shifted to gain stable footing and then picked up a rock.

“The buck must have heard me move, but I could see he had a clear path through the trees leading uphill. Sooner or later he was going to spook, and if he went that direction I knew you guys wouldn’t see him. Anyway, he stood up again and dropped his head so he could look under the branches of a big fir tree. That’s when I saw the club.”

Down below, I told Bruce that Rick was pinned down by a big buck. There was no other reason he hadn’t come out long ago.

When Rick realized that the buck he had encountered was the one we wanted, everything changed, he recalled. “I had to get it right.”

Now alarmed, the big buck turned and began to fast-walk uphill.

“I threw the rock into the trees just in front and watched him turn back down onto the contour and turn in your direction.”

Bruce and I had been watching the openings for nearly an hour, and I remarked again that a buck probably had Rick pinned down. “He’s busted,” I remember saying. Bruce shifted to dig something out of his pack, and when I looked up at the clearing there were two bucks looking back. One took my breath away.

The sun happened to be out just then and the velvet was lit up like a neon sign. I could easily see the big drop coming off the right side with my naked eye, and hissed to Bruce as I ducked into the scope.

“That’s him. Shoot him now!”

The buck had caught our movement, turned, and began to run uphill. Bruce whistled, and as the deer slowed, I squeezed. He hit the ground like a prom dress, kicked and started to tumble down the mountain.

“Shoot him again,” Bruce shouted. “Don’t let him roll or we’ll be here forever.” I did just that, and he hung up on the trail just in front of us.

Rick scrambled down to join us as we approached the buck, happier than both of us put together. We sat beside him in the grass, interrupting each other with versions of the story and struck by the unlikely good fortune that made it possible. Someone eventually noticed that the big drop tine had broken in the fall and was only held on by a thin section of tattered velvet, but that didn’t matter. In fact, it made everything even more special.

I did my Spiderman act again on the way out, if anything worse than what happened that morning, but we still made it back to camp an hour before dark. Rick concentrated on dinner while I helped Bruce feed and water the horses. Waiting while the little trickle filled the bucket, I asked myself if I’d do it again if such things were possible. I still don’t know the answer, but I’m sure glad it happened just the way it did. +++

Copies of the author’s first book, Born a Hunter, are available at the Sporting Classics Store.