Who was this strange old man who handled a shotgun like no one I’d ever seen?

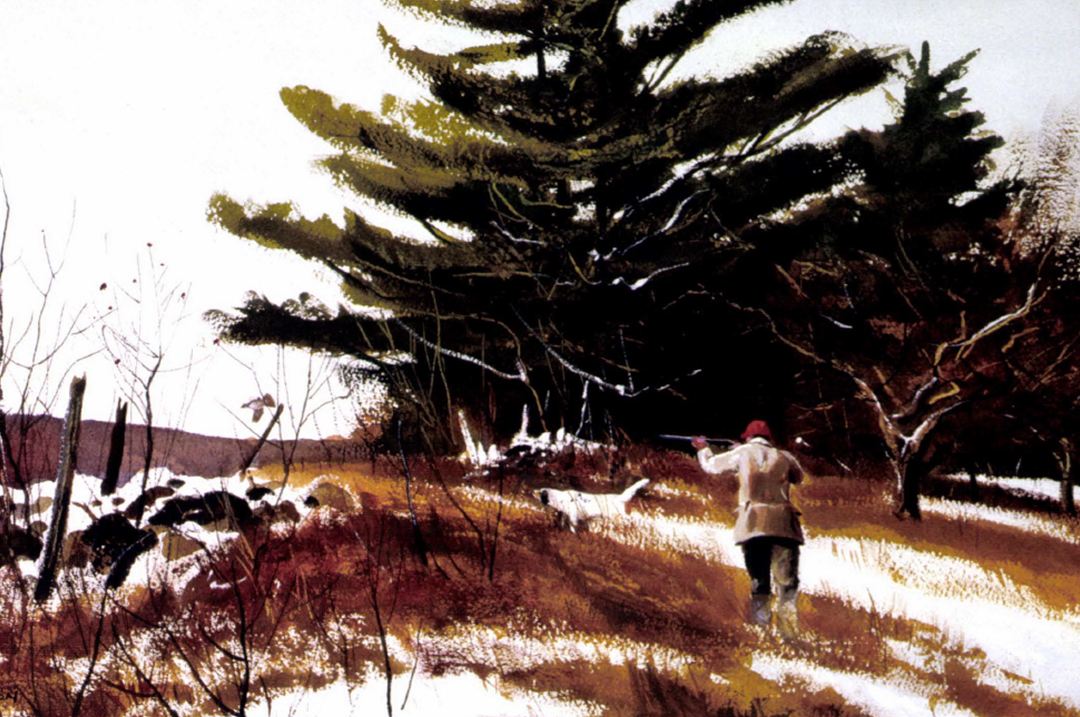

When I first saw him, I tried to duck back into the pines, but he raised his hand in greeting and I was stuck. All the while he was coming on over through the hawthorns, I cussed under my breath. It was bad enough finding a stranger in my favorite bird cover, but it would be even worse if I had to jaw with him as the afternoon slipped away.

When he got near, he whistled in his dog, a gaunt setter marked with a black saddle and brown spots above her eyes. The dog had that slight jerkiness of gait that suggests age; so did her master.

“Hello,” he said, clicking open his shotgun and crooking the barrels over his arm. “Name’s Detwiler. And you’d be…?”

“Fergus. Chuck Fergus.”

He stretched out a hand, and I shook it. A rough hand, bigger than mine, though its owner stood inches shorter.

“D’you hunt around here much?” he asked.

“Some.”

“Seen many birds today?”

“No,” I lied. “This cover’s only so-so.”

He grinned, and I knew he’d taken in the one-grouse bulge in my game pouch.

“Have you hunted this valley before?” I asked.

He nodded. “Used to quite a bit, years ago.”

“How was the hunting then?”

He smiled, lines around his eyes sort of falling into place, and reached down to scratch behind his dog’s ears. “It was good,” he said. “Wasn’t it, Kate?”

He dug in his pocket for a chaw, and I knew I was caught. As he filled his cheek, I looked him over. His coat was canvas, brush-frazzled and dotted with stick-tights and beggar’s-lice. Canvas pants and boots – those 16-inchers you see in old pictures, the kind that make even the stockiest legs look spindly – with gray wool socks folded down over the tops. On his head perched a black-and-red-checked cap, brim broken in the middle; below the cap brown eyes shone in a weathered face that could have been 60 years old, or 80.

I realized he was holding out the tobacco pouch – “Mechanic’s Delight” – and shook my head.

“Fergus,” he said, cocking his head. “I know the name from somewhere.”

I groaned inwardly. Sometimes, in filling stations, gun shops, country stores, taverns, I hear this preface followed by an identification as “the fella who writes for the ‘Game News.'” And then I can expect a rambling treatise on why there aren’t any rabbits, why the deer population’s shot to heck, and in the next breath, the 27 bucks the discourser killed off the same stand in 27 years of hunting.

“Don’t you write for that little magazine…?”

I nodded, resigning myself to an afternoon shot, to grouse and woodcock unbagged and to an inescapable ensnarement rivaled only by childhood memories of Saturdays when my parents, too smart to leave me to my own devices, dragged me from store to store while they shopped for furniture.

But the old man only smiled and let his eyes wander over the hunting cover. At length he turned, “Whyn’t we hunt together?” he said. “Kate’s pretty fair on birds, and I see you haven’t got a dog.”

“All right.” I felt relieved; hunting with the old man – however slow he might be – seemed infinitely better than standing around talking. When the old fellow shut his smoothbore, I noticed the gun for the first time. A standard American double, with a straight-backed setter engraved on the lockplates. The barrel ends were brush-whipped a fine silver-gray and the stock was nicked. A sturdy, utilitarian shotgun that looked just right in those briar-scratched hands. I supposed the old gent got it when you could still buy a well-made piece of shooting hardware – with enough fancy to make it special – for something less than an arm and a leg.

He noticed my gaze. “My new gun,” he said, turning it in his hands. “Shoots all right, and it’s got the new steel barrels. But it ain’t the same as my old Winchester.”

He flicked the double to his shoulder. “No, sir. When you looked between hammers as many times as I did, it’s hard getting used to a hammerless.”

He stopped short and watched me out of the corner of his eye. Then he turned abruptly and whistled. “Kate! Birds – go get ’em.”

The dog leaped away. She wore a bell, and its tinkle carried clearly through the late-afternoon air. The old man nodded, and we followed her into the goldenrod and thornapples. The setter was a close worker, and I saw her strike her first bird. She stopped at the scent, turned and crept to the edge of a fallen apple tree bristling with shoots. She stood high-stationed, tail straight out, like the setter on the old man’s gun.

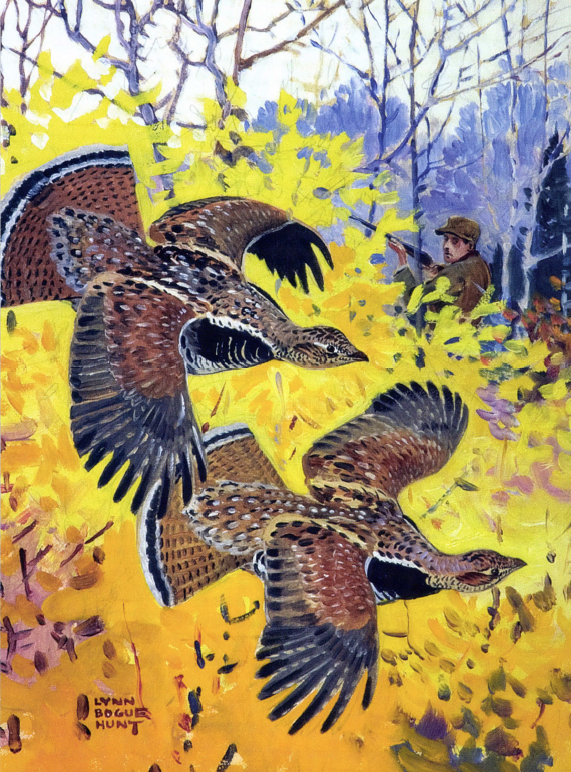

We went in and a grouse burst from the rear of the thicket, straight away and low, anybody’s bird. I got on it fast, but by the time my safety was off, feathers were adrift: and the echo of the old man’s shot was banging across the hollow.

He looked at me, eyebrow lifted. “Why didn’t you shoot?”

I shrugged. I was finding it hard to believe that an old man – What was he? Seventy? Seventy-five? – shot quicker than a 28-year-old.

“Dead bird,” the old man told his dog.

The setter had to search among the blackberry canes – she’d been screened by cover and hadn’t marked the fall but she found the grouse and brought it back.

“Cockbird,” the old man said. He held it to his chest and plucked from its tail a feather, which he poked into rotten wood atop the apple log. The feather stood like a brown-and-black banner. He pulled back his coat and slipped the bird into his game pouch, a roomy affair fashioned from a grain sack.

“That was a fine shot,” I said.

“Thanks.”

“Looks like you’ve made it before.”

The old man nodded. “Once or twice.”

We went on, the dog threading the alders before us. We had gone a hundred yards when the setter slowed on the edge of a small clearing. She crouched, sinking until her white-feathered tail touched the ground.

The old man motioned me in. A woodcock popped up on whistling wings – a sound as unnerving, in its own way, as a grouse’s take-off – and as I adjusted to the slower bird, shot and saw it fall, the old man’s gun barked twice. The dog retrieved my bird and carried it to her master. He sent her into the alders, where she found a second woodcock, and then he walked among the straight, gray trunks, bent down and held up the other half of his double.

I wished I had seen the shooting. Judging from where the woodcock lay, they had gotten up well to one side and far apart; it had not been an easy double. I nodded, quite enough communication under the circumstances, as the old man gave me my game. He opened his shotgun, withdrew the spent cases and reloaded. His shells were not plastic, but paper-wrapped.

“What did you say your name was?” I asked.

His shotgun shut with a dull click. The corners of his mouth turned up and his eyes twinkled. “Deibler.”

“Do you live around here?”

“Couple valleys north.” He shot the words back over his shoulder; already he was following the setter into the brush.

The sun on the ridge outlined November-bare trees, and in the low spots host-blackened weeds lay like matted fur. I trudged along with the old fellow. Deibler. The more I thought, the surer I was he’d introduced himself by another name. Deibler was a solid Pennsylvania name, and the old man spoke the local tongue, a dialect marked by inflection that rises and falls like the rough wooded hills; but if the name was different, the old man was more so. The clothes. The gun. The unhurried, take-it-as-it-comes posture of hunting. As if he’d stepped out of an era when game was more plentiful and time less in demand – and, therefore, fuller and more precious.

I was trying to make sense of this when I heard a grouse. The bird had flushed wild, on the other side of the old man, who had already spun and planted his feet when I looked. His body leaned toward the sound. He mounted his shotgun – a motion so fluid it almost escaped notice – swung, swung and shot the instant the grouse entered a far opening in the trees. The bird thumped the ground. It was the kind of shot I have always wanted to make, and as I watched the old man stop his follow-through and lower his gun, I knew he could have hit it time and again.

Excitement filled his voice as he called the setter and directed her retrieve. I felt very much a spectator as he took the grouse and patted the dog on the head.

We were near a tumbledown house foundation, and the old man sat on the stones. He fanned the grouse’s tail and stared at it, as if trying to read some message in the intricate play of chestnut, black and gray. I broke my shotgun and sat beside him.

We were near a tumbledown house foundation, and the old man sat on the stones. He fanned the grouse’s tail and stared at it, as if trying to read some message in the intricate play of chestnut, black and gray. I broke my shotgun and sat beside him.

“You filled your limit in a hurry,” I said.

“Did I? Oh – that’s right. They only let you take two these days.” He ran thick fingers over the grouse’s back feathers.

“How long have you been hunting?”

The old man squinted. “A long, long time. Since before this house fell down and before these fields were brush and briars.”

“I guess you’ve killed a lot of birds.”

“When I started hunting, a man dared shoot twenty grouse in one day. I killed that many a good number of times.”

He pulled a feather from the grouse’s tail and wedged it between two stones. “Yessir,” he said, “one season I shot upwards of four hundred grouse and probably half that many woodcock. Shipped the grouse to Philadelphia for fifty cents apiece.”

“When was that?”

The old man smiled, “‘Ninety-five.”

It took me a moment to subtract. “Wait a minute. That’d make you…”

“All right, call it twenty-five.”

I rested my chin on my hand and studied him. He had to be a liar. Then again, no man who shot the way he did needed to lie about anything.

“Where did you do your hunting?” I asked.

“Around here. And I spent a couple-three years up north, in that Black Forest country.” He paused. “Are there birds up there yet?”

“Not many. The woods have grown up too much.”

“You been to the Black Forest Inn?”

I nodded. “It burned down a couple of years ago.”

He frowned. “Y’don’t say?” The hollow was darkening. Down in the big valley a train sounded a crossing. Odd. I thought. Here I am talking to this fellow – whoever he is – letting the day slip away, with half a grouse limit in my pouch. No way, I thought, could the old man have hunted in 1895. And then I remembered the name: Detwiler. “So, Mr. Detwiler,” I said. “You’ve got me wondering about a lot of things.”

“That’s good. Keep on wondering.”

”I’m wondering if you’re a ghost.” I almost laughed; the words just popped out of their own accord. Mr. Detwiler spat between his boots. “A ghost. A real, honest-to-God haunt?”

I squirmed. “Not exactly. I mean, not the kind that lives in barns and old foundations and scares people.”

He shook his head. “Nope.”

“Well, then I’m stumped. I don’t know who you are, or where you come from. Only that you handle a shotgun like no man I’ve ever seen.”

He smiled. “That’s all you have to know.”

He stood and stretched, and the dog rose with a tired wag of her tail. Mist was starting down the hollow, and the apple trees looked broken-backed and full of secrets. A flight of blackbirds rushed over, and Mr. Detwiler glanced up, his face ruddy in the last light.

He looked at me. ”You take care now.”

I watched him move off. The sumacs and locusts closed around him. The tinkle of the setter’s bell faded and vanished in the high, thin breeze. I reached back and slipped a hand in my game pouch. My fingers touched the grouse, soft and cold. They closed around the long, thin bill of the woodcock. I looked at the talisman between the stones, and I knew I would search for grouse feathers many years to come.

Outdoor Chronicles is a collection of outdoor stories that will make you laugh out loud, and want to carry them wherever you go. They range from a fishing trip to Canada to a little stream that was better than remembered, to how the baby boomers almost trampled a sport to death, to a solitary trek during a cold, dark, and dreary February, and many more. Buy Now

Outdoor Chronicles is a collection of outdoor stories that will make you laugh out loud, and want to carry them wherever you go. They range from a fishing trip to Canada to a little stream that was better than remembered, to how the baby boomers almost trampled a sport to death, to a solitary trek during a cold, dark, and dreary February, and many more. Buy Now