And then, in an instant, everything changed. We found a track. I stood over the indentations in the snow where a lion had crossed the trail. I marveled at their intrigue and raw beauty. Since I began hunting with hounds seven years prior, tracks ceased to be simple divots in the snow. Instead, each set of tracks represented an adventure to be had and a story to be told.

A single fearless hound goes head-to-head with a huge tom cougar in the Idaho backcountry.

I knew a mountain lion could bound over 12 yards in one leap, reach 50 miles per hour sprinting, and kill a moose. What I did not know, however, was that the fully grown tom mountain lion with the aforementioned skills was laying just 15 yards away from us deciding his next move.

The hunt was planned weeks in advance. I would be joined by my hound hunting partner, Chess Carbol, his dad, Courtland, and his brother from out of state, Quinn. The three prior weeks of the season had proved fruitful for Chess and me. The snow was there, the tracks were there, and the dogs had worked their magic and turned every lion track we put them on into a cougar in a tree.

Yet, I knew this day was unlikely to be a successful hunt. Snow is almost always a good thing when lion hunting, unless it snows the entire night, which it had. Before light, we had driven miles of forest service road through the blizzard hoping to cut a fresh track from a lion or bobcat moving during the storm that we could turn loose on at daybreak. We found nothing, but we had a plan for daylight that would keep us away from other hunting competition.

We would hike a large loop in a roadless area hoping to find a track to run. There is a reason the vast majority of houndsmen only hunt from trails accessible to trucks, ATVs and snowmobiles. It is easier and generally more effective. Also, most hunters simply do not want to risk a lion going 5 or 10 miles in the wrong direction after hiking 5 or 10 miles into the backcountry. It happens, and it makes for a very long day. Half of our hike was uphill, and all of it in deep snow, but since no one else was foolish enough to do it, we had the drainage to ourselves. We left the trucks at legal light just as the snow quit falling.

Drama, the author’s English redtick female, leads the way at daybreak into the snowy Idaho backcountry.

As our hunting party of four men and three dogs ascended in the deep snow, we forged ahead to the highest peak in the range. It was not the most imposing mountain in Idaho, but it marked the halfway point of a 12-mile loop we were hiking, and it was no cakewalk in a foot of fresh snow. We found no lion tracks.

When we reached the windblown summit we had set out to climb four hours prior, the fog robbed us of what I knew to be a spectacular view. It was time to finish our loop back toward the truck, thankfully downhill, and in canyons protected from the wind.

Our hunting party decided to split up to cover more ground, knowing we’d be lucky to cut just the tail end of a lion’s movement from the night before. Chess and Courtland took a heavily wooded canyon with a more direct approach to our trucks, while Quinn and I took another canyon that would put us at the base of the mountain a few miles apart. I held on to Drama, my English redtick female, while Chess and Courtland took their English/Plott cross puppy, Luna, and my little red hound female, Sparta.

A few miles later, just as the snow started to pick up again, we cut the track.

I called Chess immediately. “Looks like we might see a cat after all.”

Drama’s vicious barking kept the lion from leaping down and fighting the dogs.

“Really?” he said. He sounded surprised. He’d hunted lions long enough to know the chances of a runnable track in the conditions we had.

“I think it is a decent track, but the snow is so deep it is tough to tell. It is from this morning and is headed back into the big loop we made towards you guys. I bet it is bedded up in one of the three or four brushy canyons between us. It might take some leg work to walk out some of the wind-blown slopes.” I pulled the phone away to look at the time. “It’s about 2 o’clock so we have plenty daylight. Just try to stay on the high side of the ridge so you have reception. I’ll let you know what happens.”

I killed the call and looked up to see Quinn 15 yards off the trail kneeling between two large sage brush bushes. I walked over. The snow had been dug out to the brown dirt and green grass underneath in a large circle. In the melted snow on the outside of the circle stood the very large pad mark of a mature tom lion. Then we noticed the tracks of the lion from where it ran out of it’s bed toward where we’d come from.

We looked at each other in disbelief.

“The cat was laying here when we walked by,” I said. “He took off while I was on the phone.”

It felt a little spooky knowing the killer was so close without us noticing.

“Where’s Drama?” Quinn asked. I had not been paying attention. I looked down on my GPS and saw she was 300 yards away, but right near the trail we had come down the mountain on. She was moving fast. I smiled.

“She is back up the trail where we just were. She’s on the lion, but she’ll be silent until she sees him,” I answered.

In the distance, Drama sounded off, her voice cut through the crisp air and reverberated down the canyon. Her bark was fast, urgent and pleading, and the echoes made it sound like an entire pack of hounds, but it was just Drama living up to her name.

“C’mon!” I told Quinn as I started running towards the sound. Having a lion jumped close enough to possibly see climb is very rare, and I did not want to miss it.

The barking continued for almost a minute as the foot chase unfolded. The lion ran up out of the canyon into the sage and turned hard back down towards the aspen trees in the valley. There was a brief silence when they hit the bottom of the canyon. Then I heard the steady chop Drama uses when she has treed something.

A high-jumping Drama comes eye to eye with the treed cougar.

We made our way to the tree and peered up at the lion. He was clearly a male and definitely a very nice one, large in the head and exceptionally long in the body. The tree was small, its base no larger than my thigh, and the lion was only ten feet off of the ground. Drama’s speed and tenacity had not left him the luxury of choosing a bigger tree.

I could tell the cougar was not comfortable being so close to the ground and Drama’s vicious barks. The great cat started to move from tree to tree like some sort of gargantuan-sized squirrel, with Drama following under him, baying vigorously. Branches bent and snow fell off the limbs as he traveled further down the canyon. Knowing a ground fight was much more likely after a cougar jumps from a tree, I was worried. The trees got smaller and the branches got thinner, and when he tried to support his weight on too small of a branch, it snapped. He dropped to the ground almost on top of my dog.

The lion lunged out of the snow with Drama just behind him. With teeth bared, she let off a machine gun fire of fierce barks just inches from his tail; evidence that, for the moment, any domestication she’d acquired had been replaced by the wild within her. She transformed into a beast completely unbridled and as savage as anything in nature. She was no longer a trespasser into the wild, but a long lost resident returned home; the only evidence of life in another world was the collars and antennas around her neck.

Nick Muckerman with Sparta and Drama at the tree. The hounds were leashed before the shot for their safety.

In an absurd deviation of logic, the lion, easily 160 pounds with the tools and strength to take down an elk, refused to confront the 40-pound dog at his heels. Regardless of knowing that this illogical rule generally stands true between even a single fearless hound and an adult cougar, the situation made me uneasy. Although I had hound hunted for seven years without a dog killed by a lion or bear, Murphy’s Law can be nasty and unforgiving. With a wild animal four times her size, and with no pack to support her, propensity can become reality in the blink of an eye.

I could barely see Drama and the lion ahead of me through the frenzy of snow kicked up by the two predators, but I charged toward the moving melee. My Glock .40 was on my hip, but I knew that if the lion decided to turn and fight her, he could turn my dog inside out before I could intervene. There would be no truce between dog and cat. Even a few hounds can hold their ground and fight an adult mountain lion too prideful to climb with varying results. But with just one hound and a tom lion, the conclusion would be written in the snow with my dog’s blood.

The lion stopped.

When he turned, he bared his teeth at my dog and stood, for a moment, tall and proud with lithe muscle bulging through his tawny hide, a sight of unimaginable beauty through the falling flakes of snow. Drama stopped, just out of reach of the great cat’s razor sharp and bacteria-ridden claws. Then the cat crouched in the snow and waited like a coiled spring. I had no plans of personally killing a lion on this day, but I knew I needed to before something bad happened to my dog. The angle offered no safe shot. I was stuck. If I moved too much and Drama sensed me, she would dive into the lion, thinking the lion was a threat to me. She’d done it before on a female lion, but it had only cost her a trip to the vet. The stakes were higher now. My dog’s life depended on what she did next.

Drama’s wolf blood, present in all dogs, but least far removed from the pursuit hounds, forbid fear, because fear was weakness, and weakness in wild places meant death. On this day, I knew the fearless would live, and the fearful would die. The only thing a 160-pound apex predator might fear is an animal crazy enough not to be afraid of it.

My hound crouched, muscled tensed, ready for a fight, and then crossed the line from reckless abandonment to pure, unbridled insanity.

Still baying hard, she stepped toward the cat and at the same time her voice turned over into a deep, long bawl, raspy and raw, a vicious battle cry that spoke of impending violence and total fearlessness that I had never heard from her.

It is not size or reputation that determines who reigns supreme in the day-to-day brutality of nature, but simply who is chasing and who is fleeing. The cat turned and bounded 20 yards before scurrying up a tree like a frightened squirrel. It was over. Drama would live; the lion would not.

At the tree, it seemed he was much more comfortable with his distance from my dog, as well as the strength of the branches under his feet. Scanning around and seeing this was indeed the biggest tree around, and considering he now had some apparent visceral fear of the crazy, undersized, red-ticked wolf at his feet, I was hopeful he would not jump out again.

Quinn Carbol strains to heft the mountain lion, the next-to-largest of more than 70 cougars the author has chased in his career as a houndsman. With Quinn are his father, Courtland (left) and brother, Chess.

I caught my breath and called Chess.

“We’re treed,” I told him.

“That was fast.”

“He was bedded 15 yards from where I was standing when we spoke last. Try get over here as soon as you can. He jumped the first tree and we almost had a ground fight. I don’t want that to happen again.”

“My dad is really struggling,” Chess told me. “His knee is killing him.” I knew Courtland had limited motion of one of his knees after a knee replacement surgery. Walking through a foot of snow all day in the Idaho backcountry had been no easy task. I asked if he could make it in the three and a half hours we had before legal shooting light expired.

“I think so. It’ll just take us a bit,” he responded.

Quinn and I warmed ourselves with a small fire we built while Drama let the world know she had found and treed the biggest, baddest lion on the mountain. Just before five o’clock, Sparta came barreling in and started treeing alongside Drama. Soon we could see Chess and Courtland. Chess looked tired. Courtland looked alive, barely.

“You missed the show,” I told them. Chess laughed. Courtland did not. He just stared up at the beast above him, catching his breath. I told Courtland I’d seen over 70 lions in my time as a houndsman, and only one had been bigger.

With the fading light, Courtland did not have much time to admire the lion. He had seen some females on prior hunts, but this was the first shootable male he had laid eyes on. He pulled out his .45 automatic, and Chess and I tied up the hounds. To the houndsman, the shot is anti-climactic. The chase is what keeps him headed back to the mountains time and again. When a kill happens, though, it is a special time because usually it only comes around every 10-20 lions treed.

At the shot the big cat tensed and stumbled for footing. The shot looked perfect, but I yelled over the howling dogs to “hit him again!” I’d rather have his taxidermist do some extra sewing than my veterinarian in the event the lion came out wounded. A second later the .45 barked as Courtland sent another hollow point into his chest. The cat went limp and fell through the snow-covered branches. He was dead before he hit the ground.

Chess unhooked his puppy, Luna, and she approached the fallen giant with extreme caution, inching closer and closer until she could smell the cat just inches from her nose. She was young and would pull her weight with the pack one day. The genetics were there. I’d just witnessed her mom come face to face with the lion, and almost certain death, and not back down. Indeed, Luna would run with the big dogs soon. But on this day, she was just along for the ride and gaining experience with game.

After Luna got a few sniffs, I asked Chess to let Drama off her lead next. She left the chain like a horse from the chute and attacked the lion with intense ferocity, worrying the skin with low, guttural growls. It was her well-earned reward.

After some pictures in the fading light, we huddled around the fire and skinned the lion for a life-size mount that would one day memorialize not only this hunt, but the other lion hunts Courtland had been a part of where the only shooting done was with a camera. I knew the great cat would be displayed in a place of honor, as is fitting for such a magnificent beast.

It was a few miles of hiking by the light of our head lamps before we made it back to where we had begun over 12 hours before. Hiking to find tracks is immensely more work than running a track from a road, but I have found that the satisfaction of hunting this way is compounded by the amount of work expended. This day it certainly proved to be true.

After the Carbol crew’s taillights disappeared down the canyon, a dark silence fell as I sat on the tailgate of my truck with my two hounds and reflected on the hunt.

I pondered the life of the lion we had killed and what he had seen as a silent killer and warrior. He had undoubtedly been on many great hunts himself or he would not have reached maturity. Even among other males, he had fought his way to dominance or we would not have found him in such a game-rich piece of real estate with an abundance of female lions around.

I revered him more than the other large predators of the American West. Unlike the wolf, he hunted alone, with no pack and with no companions to pick up his slack if he had an off day. For him, too many off days in a row would have reduced him to raven food. And unlike the bear, when the cold and snow came, he did not take a five-month nap waiting for the butterflies and rainbows of spring to make a living. Also, grass and berries were not on his menu. Instead, he stalked the mountains in ultimate secrecy and supreme stealth for years on end, taking deer, elk and moose and leaving behind nothing but tracks and the bones of the slain. He had ruled the mountains and I felt honored to have trespassed in his domain.

After a long day of intense pursuit, Drama gets some well-deserved rest.

I looked down at Drama and she looked up at me with her tired eyes. It had been a long day, and it was her third day in a row, having treed females the previous two days. But I knew that if there was another track to run, she would snap out of her stupor and run it to its conclusion or die trying. The relentlessness of a well-bred hound dwarfs that of even the most dedicated human hunter. Yes, the lion is king, but he had just been brought to bay by 40 pounds of red-ticked hair and heart. Lots of heart.

Surrounded by falling snow and an eerie silence broken only by the soft breathing of my exhausted hounds, I stared through the darkness into the canyon that held years upon years of memories. The renewal of fresh snow would hide the tracks and the blood of the day, and those secrets would be lost to all except those who experienced them. Yet with the new snow would come fresh tracks and new memories to make. Sometime soon, I would again hear the beautiful song of my hounds echo through these mountains. One day, God willing, after Drama has breathed her last, I will listen to the sound of her puppies in hot pursuit of the progeny of the great tom we’d just killed. But I knew the memory of this hunt, this magnificent lion and this fearless little hound, would endure long after the snow was gone.

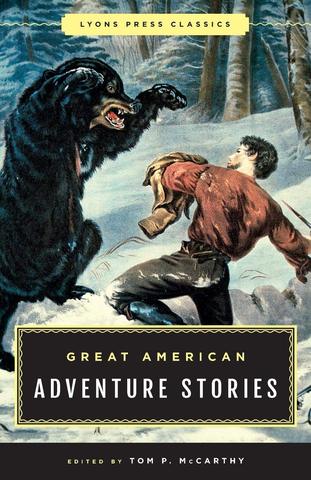

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today.

Created for adventure addicts there has never been a more exciting collection of stories that celebrate the indomitable spirit of the American character. Shop Now