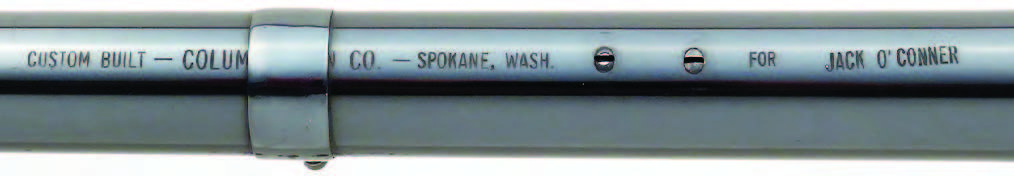

For gunmaker Al Biesen, misspelling Jack O’Connor’s name was a tiny mistake, but something he would never be able to live down.

Spokane was as far from her family as my rightfully cautious bride would move, at least in the direction of Montana’s elk country, so we set up housekeeping there in the early ’80s. Kellie immediately found gainful employment that kept us in beans and soup while I flogged away at the licensing requirements the state of Washington deemed necessary before I could become forever miserable in my chosen career.

The one bright spot, at least back then, was that Spokane hosted proper gun shows twice a year. Hailing from a town so small that the department store couldn’t legally sell anything beyond a training bra, these events were a new and welcome experience. I was barb-hooked after my first day, mostly because the commercial potential seemed promising.

After reserving a table for the next show, I began scouring the local newspaper for stock. Ever supportive, Kellie let me invest the money we needed for rent, but it soon became apparent that I needed to sell some guns before the next show came around. Going big time, I placed an ad in the Sunday paper and held my breath.

That classified headliner was an unmolested pre-’64 Winchester Model 70 action, which, at $350, I figured would be gone before brunch. I did relocate a couple of clunker pistols that first afternoon, but no one called on the action, so I’ll admit to being surprised when the phone rang early Monday morning with a hit.

“You the guy with that old Winchester 70 action? I’m a gun cobbler and might need it one of these days,” someone said in a big, growling voice without so much as starting with hello. Even through the gruff, I could hear a smile.

“OK if I come take a look?”

I invited him right up.

“I’ll be there in the early afternoon, and I’ll bring along a couple of the guns I put together. Maybe you’ll want one of them in trade.”

“My name is Dwight, and I look forward to meeting you,” I threw back.

“Al Biesen. See you around two this afternoon.”

Having read pretty much everything Jack O’Connor had ever written at least ten times, I knew about Al Biesen and the tremendous quality of his work. To think that the gunmaking legend was coming to my house and bringing a rifle or two was quite honestly more than I could comprehend. Kellie pitched in to help me tidy up the place, and even mopped the kitchen floor—twice.

“I’m not doing that again, so the next time you wet yourself, do it outside like a grown man!”

Al knocked on the door right on time. He hit me with a big smile, flashed those twinkling eyes, and popped my fingers with a crushing handshake. I couldn’t help but notice he had a pair of gun cases in his hand.

I invited him in, offered coffee, and then suggested he take a seat on the couch.

“I’m a little grimy for that,” he shot back, then surprised me by plopping himself and those cases right down on the carpet. I followed his lead, but quick.

“You been trading guns long?” he asked, knowing full well the answer. Still, the question made me feel more comfortable and gave me an opening. I told him the truth, then quickly added that I was more than a little familiar with his work, at least by reputation.

Biesen hit me with that smile again.

“Bet you’ve read some of that stuff O’Connor wrote about the rifles I made for him.”

“I sure have, but I’ve never seen one of yours for myself.”

With that he unzipped one of the cases, broke open a spectacular Winchester Model 21, and handed it over.

With that he unzipped one of the cases, broke open a spectacular Winchester Model 21, and handed it over.

“This one’s waiting for a client to pick up, and by that I mean pay off. I had a fellow by the name of Terry Wallace engrave it, which added to the cost considerably. Here, take a look at that pheasant with this magnifying glass.”

A first-time father never handled his newborn with more care.

Although not engraved, the rifle Al brought along was even more to my liking. It was a 243 Winchester. I remember being surprised that someone would order a custom rifle in such a modest caliber, and must have voiced something about just that.

“Most of the rifles I build are for big game, but there have been some in lighter calibers or set up for varmints. I even built a .22-250 for Jack O’Connor a long time ago. He liked that rifle, too, even though I spelled his name wrong on the barrel!”

I didn’t believe him, and the shock was apparent.

“I worked for the Columbia Gun Company back then,” Al added, “and somehow managed to stamp ‘Made for Jack O’Conner’ right on the top of the barrel. I never was able to live that one down!”

Al stayed until it was time for dinner, telling stories about hunting and the gun trade. Before leaving he wrote out a check for the Model 70 action and invited me down to his shop. It killed me to wait and take advantage, but he treated me like royalty when I knocked on his door a couple of weeks later. I asked about the “O’Conner” rifle again, prompting a few more tales about his relationship with Jack and other famous clients.

It would have been easy to become a pest at Al’s shop, but I resisted temptation and only called when I’d found something or other he might find interesting. We bumped into one another on occasion as well, but I never did ask him about the .22-250 again. I thought about it occasionally over the years, and I saw a photo for the first time when Tom Turpin’s Modern Custom Guns was published. Of course, I turned the story over in my mind again upon learning of Al’s recent passing.

Imagine my surprise when, just last week, a client asked me if I would be interested in handling the sale of this very rifle.

“There’s an interesting story that goes with this one,” he began. I suspect he was more than a little surprised that I had one of my own.

Made in 1948 near the end of his tenure with the Columbia Gun Company and when the cartridge fit only in the chambers of wildcatters, the 22-250 was actually the third rifle Biesen prepared for O’Connor. It remains in superb condition and still wears the same Leupold scope that Jack acknowledged as his favorite optic for this rifle.

For gunmaker Al Biesen, misspelling Jack O’Connor’s name was a tiny mistake, but something he would never be able to live down.

The bore is beginning to show slight wear but remains viable. The owner has fired fewer than 60 rounds through it since purchasing the rifle in 1995.

In the July 1969 issue of Outdoor Life, O’Connor wrote of this rifle: “I have had my present .22/250 for 20 years. This particular rifle is a sort of a rare bird. The action is a high-number, nickel-steel Springfield, shortened for the .22/250 cartridge. A piece has been cut out of the bolt and out of the receiver. The parts were cunningly welded back together and polished. It was so skillfully done that the weld defies detection. Stock is by Al Biesen and is one of the first he made after he moved from Wisconsin to Spokane, Washington. Metal work was done by Columbia Gun Company, an outfit that went out of business in the early 1950s, I believe. In the score of years I have used this custom .22/250, it has worn a variety of scopes, but presently is equipped with a Leupold 7 1/2X. It has a 24-inch barrel and weighs 8 1/2 lb. This is heavy enough to shoot quite well and light enough so that it is not very burdensome to carry.”

In a final, unbelievable twist, the .22-250 is well-addressed in Anderson and Buckner’s biography, Jack O’Connor, The Legendary Life of America’s Greatest Gunwriter. Incredibly, the book lists the serial number as 3127703. The correct serial is 3127765, upper portions of the last two numerals being obscured. I’ll bet knowing that would have made Al feel somewhat better about his mistake.

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Shop Now

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Shop Now