Trophies—we hunt for them, fish for them, incur inordinate amounts of expense and trouble. Most times the shooting or the hooking is the easy part. That Cape buffalo head—cleaned, crated, dipped, shipped and wrastled through Customs, will likely cost more than the hunt—and that’s before a taxidermist ever lays a hand on it. And fragile and technicolor billfish? Hang on a minute, I feel a story coming on.

Captain Bee ran the night ferry to Daufuskie. Daytimes, he was the island postmaster. So when I blew ashore there and reckoned I’d stay, I went looking for Captain Bee early one drizzly afternoon. The post office on Daufuskie was down by the county dock, in the back of the general store, which is in back of Mudbank Mammy’s, the concrete floor beer joint where they sweep up the eyeballs come closing time. It was a right civilized arrangement. A man could sit around, jaw with his buddies and tip a few while waiting for his mail. Years later, the Postal Service got wind of it and shut the whole thing down, for all the right reasons, they said. But it worked just fine, for a while at least.

“I had to find a motel and trade cars before I could get him home.”

Captain Bee had already sorted the incoming letters, canceled a fistful of outgoing ones and sold the daily ration of money orders to folks—who, for reasons you didn’t ask about—don’t have checking accounts. He was hooked over a cool one, the lonesome curl of his last smoke still rising from the ashtray.

“Cap Bee,” I asked, “you got a spare post office box?”

Captain Bee was always careful to change the little numbers in the stamp while he could still see them and half-drunk, he could run a boat better than most men half-sober. Too much time on a rolling deck, his knees rattled like marbles in a bucket. He pointed over his shoulder.

“Fetch me up that cigar box. There, atop that stack of beer.”

He rummaged through a cluster of derelict and tarnished keys, held a specimen up for inspection. He licked it, turned it toward the rain-spattered window and squinted.

“Go find a box it fits. If it’s got somebody else’s mail in it, go find another.”

The boxes were cut into the back wall, half in, half out, where you could get your mail odd hours unless it was raining or the copperheads were crawling. That’s when I noticed the sailfish, an iridescent rainbow above the Mudbank Mammy’s bar. No pot of gold at the end, but a big jug of Jose Cuervo about the same color.

“Nice fish,” I said.

Captain Bee waxed eloquent in sundry blasphemies. “My uncle down in Fernandina was goin’ in the nursing’ home. Said I could have it if I come get it.”

I’d never caught a sailfish. Not yet, anyway. “What’d he weigh?”

There was another powwow of cussing. “I don’t know, but I can tell you he’s 107 damn inches. I had to find a motel and trade cars before I could get him home.”

And then one day I was off to Pompano Beach to pick up my own sailfish, a 120-pounder I’d wrestled from the Pacific Blue.

A fiberglass fish just like his. Yeah, I like plastic less than you do, but we don’t kill billfish anymore. At least we try not to. Sometimes a shark will cut one up or sometimes they will throw their guts and you know they will likely die but still you try to make it right with the butt end of a long-handled gaff. Catch ’em, kiss ’em, tell ’em goodbye.

But first I took pictures and pulled tape. Bob Dowling at Gray Taxidermy was all over it.

“You might say I have a vested interest in catch-and-release,” he said over the phone. “You turn him loose today, somebody else might catch him tomorrow and I’ll get to mount him again.”

Right away, we laid a campaign. I was gonna beat the high-priced trophy scenario. Bob would make me a plastic fish and I would drive down, tour the place, shake his hand, save the freight and get in a little fishing too. Gray Taxidermy was in Pompano Beach, and Key West was only another 200 miles.

I got overly attached to a poem one time, An Idea of Order at Key West, by Wallace Stevens, about when he came upon a woman singing on the beach at sunset. He spun it up so a lot of things made sense, why we sing, why we write and even why we might want to hang plastic fish upon our walls. But it doesn’t say anything about what happened right afterward.

It’s like a carnival set up in a fish camp that never left. And I was about to deal with another mean right hook.

Stevens walked up the beach and down a dock and got suckered into boxing Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway had cranked in a lot of big fish and his right arm showed it. He confused the poet with his left, then broke his nose with a mean right hook.

Wasn’t much order in Key West in those days, still ain’t. Crusty local Conchs, Cuban exiles, dope runners, gun-runners and every desperado on the East Coast that drifted south long enough. Throw in—on any given night—eight or nine hundred cruise ship passengers and a couple of thousand sunburnt Canadians, bevies of baffled Midwesterners, assorted street musicians, panhandlers and pickpockets, and get everybody but the pickpockets just as drunk as you can. It’s like a carnival set up in a fish camp that never left. And I was about to deal with another mean right hook.

I didn’t throw a punch, and I didn’t take one, good thing. When I got licker slopped on me in Sloppy Joe’s, I figured it was my own fault for following Hemingway around. I steered clear of the Garden of Eden, where you could shuck your britches at the door, and when I chanced upon the wrong masseuse I politely put mine back on and went about my business. A man had best be careful in that town.

But there was a mean right hook in the sky, a 200-mile-long comma of wind and rain hanging out in the Gulf of Mexico, bearing down on the West Rocks, right where the grouper were biting. The skippers who had ridden the weather ashore the day before wouldn’t even answer the phone.

They call it the Duval Crawl, what you do when you can’t get out to fish. Up one side of Duval Street and down the other, cafes, shops, boutiques, bars, bars and bars. The process can eat up most of a day, most of the night, too, if you’ve worked up a sufficient thirst. And then the squall finally blew ashore and suddenly there were cigarette butts floating in my shoes.

I called Gray Taxidermy. “I’m coming to get my fish.”

“Tomorrow’s Saturday, sir. We close at noon.”

Overseas Highway US 1 North is the longest 127.5 miles in the world, even longer in the rain. They call one bridge the Seven Mile Bridge and they mean it. One shift of tourists leaving, another on the way in and it was bumper tight all the way to Homestead and then another hundred rainslick miles to Pompano.

You could see Gray Taxidermy a good ways off, from the giant marlin in the parking lot, modeled after the unofficial record 3,500-plus-pounder landed off New Zealand a couple of years back. But time was tight, too tight, and—damnitall—the front door was already locked.

I beat feet around back, slithered through a crack in the chainlink and introduced myself to the first man I found. He went and found help and they began shuffling through boxes the size of pool tables until they found one with my name on it. Did I catch a fish that big?

“What you got to carry it in?” they wanted to know.

Didn’t matter, I could see right then it would not fit. Plan B was the roof rack and the length of anchorline I’d bought in Cudjoe Key, but there in that driving rain that would do me no good either. And that’s when I remembered Captain Bee and another rainy noontime a long time before. Trade trucks? No way!

“Ship it,” I said.

“Where to?”

“Daufuskie Island, South Carolina.”

“Da-where? You got your credit card?”

I did.

Bingo, my sailfish was right on target. The trophy cost more than the fish.

Cover: Thinkstock/JW

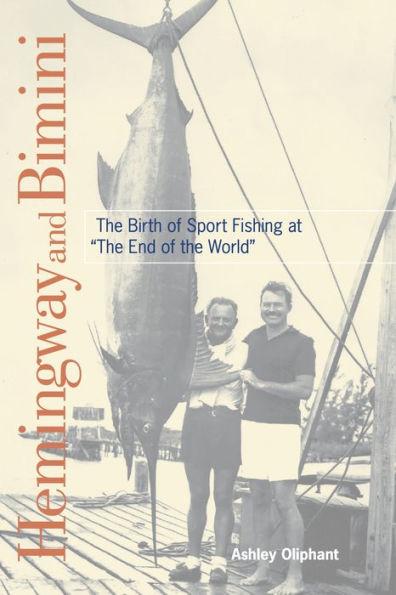

Follow Ernest Hemingway’s exploits on the Bahamian island of Bimini from 1935 to 1937, the very moment in time when the International Game Fish Association (under the author’s co-leadership) was emerging. Covers Hemingway’s role in the formation of the IGFA, his underappreciated seminal writing about competitive saltwater angling when the sport was still in its infancy, the amazing fishing he enjoyed on the island, and the way all of these experiences translated into the composition of his posthumous novel Islands in the Stream.

Follow Ernest Hemingway’s exploits on the Bahamian island of Bimini from 1935 to 1937, the very moment in time when the International Game Fish Association (under the author’s co-leadership) was emerging. Covers Hemingway’s role in the formation of the IGFA, his underappreciated seminal writing about competitive saltwater angling when the sport was still in its infancy, the amazing fishing he enjoyed on the island, and the way all of these experiences translated into the composition of his posthumous novel Islands in the Stream.

This is the only book on this period in Hemingway’s life and reveals unexpected dimensions to the Hemingway portrait that deserve attention, including his surprising humor, his advanced conservationist views several decades before the environmental movement even began, and his egalitarian ideas about his contemporary female counterparts in the big-game fishing world—challenging the usual portrait of Hemingway as a chauvinist with no personal rules, boundaries, or conscience. Includes beautiful vintage photographs of 1930s Bimini that have never been published in book form. Buy Now