Bear Scare

Notwithstanding painful and humiliating memories of an early Boy Scouts endeavor that landed Mollygrubs in a world of woe thanks to turning poison ivy leaves into ersatz toilet paper, he remained a loyal, enthusiastic member of the local troop. That was thanks in no small measure to his scoutmaster, a genial old fellow with an amazing level of tolerance for the high jinks, rowdiness and unbridled enthusiasm for those he supervised an instructed. Mr. Dockery (no boy dared to call him by his intriguing given names, Simon Peter) and his wife had no children of their own, but just as she cherished and nurtured the second graders she taught, he devoted himself and his considerable knowledge of the outdoor world to the exuberant youngsters forming the local Boy Scouts of America troop. Moreover, being a sensitive soul who recognized the characteristics that led to Mollygrubs being the fall guy for every prank and a mobile mess of misfortune who could somehow conjure misery out of pretty much any situation, he tried valiantly to avoid misery befalling his “special project” scout.

Yet he seemed every bit as much doomed to failure on that front as Mollygrubs was fated for the youthful equivalent of Falstaffian folly. A prime example came out of what seemed the most innocuous of scout outings, a three-day backpacking/fishing/camping trip in the nearby national park. The adventure offered multiple opportunities to earn credit toward acquiring merit badges, and for all that he seemed a constant study in ineptitude in the outdoors (and elsewhere), Mollygrubs was well along the road to becoming an eagle scout. That was a testament both to his father’s determination to make his offspring an outdoorsman and the persistence and patience of his Scoutmaster.

On this particular outing there was first-rate fly fishing to be had in the stream that was their destination; getting there involved backpacking and utilization of an array of skills in that arena; and once camp had been established, fishing and foraging offered ample chances to utilize cooking skills. Mollygrubs was determined to make progress toward earning badges in all three fields, and initially things went quite well. He was responsible for finding and correctly identifying some edible mushrooms (the same morels or “Merkles” that had brought him such woe with the lovely Mitzi Merkel at the Junior Sportsmen conservation banquet), and since it was springtime, others in the group successfully sought more wild edibles in the form of ramps and branch lettuce. They had brought along plenty of potatoes, so all that was required to prepare a backcountry feast fit to rival any fare offered by four-star restaurants was enough trout to feed a bunch of hungry boys.

Fortunately, several of the scouts were already fairly accomplished anglers. Even fumbling, stumbling Mollygrubs who, when he wasn’t retrieving his trout fly from streamside trees (his buddies said he was “fishing for squirrels”) or falling and “floating his hat” while wading with amazing regularity, managed to land a brace of trout. An objective onlooker who had watched his maneuvers with a fly rod might justifiably have concluded the two trout needed to be removed from the gene pool, but Mollygrubs was inordinately proud of contributing, even in a meager way, to the key ingredient for the upcoming feast. Since several of his fellow Scouts along with Scoutmaster Dockery had landed a limit of five trout, there were fish aplenty for everyone

With close supervision Mollygrubs managed to fry the trout, all appropriately adorned in cornmeal dinner jackets, while others peeled and cooked potatoes, sautéed morel mushrooms and fried some bacon so the grease and bacon bits could be used to dress a traditional mountain salad of ramps and branch lettuce by “killing” the greens. A “kilt” salad, one of the most cherished foodstuffs of a mountain spring, involved using hot grease to wilt the key ingredients, ramps and wild lettuce. While undeniably delectable, when consumed ramps did have some rather remarkable side effects. They produced a pungency of breath in those who partook of them so powerful it made garlic seem like a pantywaist pretender. The halitosis lingered for days, not hours, and was of such a nature that anyone in the group ate ramps whether they liked them or not. Once you consumed them, the ability to smell them on others magically disappeared, so whether out of pure culinary enjoyment or self-defense, everyone consumed ramps in such settings.

Another side-effect of ramps, and indeed the menu in general, was that collectively the foodstuffs, especially when joined by lots of grease used in cooking and plenty of exercise on the trail and in the trout stream, had a purgative impact that shamed commercial products such as Metamucil. Since Mollygrubs had a pronounced tendency towards gastric distress and tummy turbulence, not to mention a penchant for eating sufficient quantities of food to give him a well-earned reputation as an adolescent trencherman, it came as no surprise that after the sumptuous streamside supper he was the first to experience a quite urgent need to answer nature’s call.

This time, thankfully, he didn’t face the kind of situation that had troubled him a few years earlier in the poison ivy escapade. The scouts’ campsite was actually equipped with a rudimentary but fully functional outhouse. It wasn’t really a true replica of “that little house outback,” but rather a ramshackle affair with a seat over a five-foot pit with a fiberboard exterior. The rudimentary affair even had a roll of toilet paper and a coffee can filled with lime to dump in the pit from time to time to lessen the smell.

At the moment, Mollygrubs gave little thought to outhouse aesthetics or indeed anything except performing his version of the backwoods quick step as he hastened to get relief from his gastric distress. Alas, one of his fellow Scouts, in an action directly countermanding strict orders from the Scoutmaster, had used the site as a dumping ground for the scraps from the night’s trout feast and trimmings. This was strictly verboten because they were squarely in the middle of black bear country, but the lad who had been assigned the task and a provided with a shovel to bury the material had been afraid of being in the dark by himself. He just slunk off and, and the passage of what he considered sufficient time, dumped everything down the outhouse hole.

That had attracted a young bear, which had long since scented the toothsome flavors wafting through the spring air, and once full darkness fell, the bruin entered the slap-dash enclosure with ease. That was where matters stood when Mollygrubs opened the door and, just as he loosened his pants and readied to address an urgent internal problem, discovered he had company.

Accounts of what ensued varied appreciably, but all were in agreement on certain key points. Mollygrubs screamed and the bear, equally surprised, knocked over the fragile structure as it hastened to escape. The misfortunate boy’s antics must have been something to behold as he staggered toward the light of the fire, pants around his ankles, while making progress remarkably similar to that of competitors in a three-legged race and screaming “Bear!” at the top of his lungs.

As for the bear, likely a male adolescent that had experienced some growing pains connected with its mother similar to those Mollygrubs knew all too well, once it managed to scramble out of the toilet pit and completed the wrecking of the outhouse structure its human counterpart had begun, it lit a shuck for safer territory. Humans and tempting foodstuffs such as fish bones and leavings from fried taters had suddenly lost all their appeal.

From the third-party perspective of Mollygrubs’ fellow Scouts and their erstwhile scoutmaster, recollections of the overall adventure differed somewhat. However, all agreed on two points — that Mollygrubs’ attire was befouled beyond redemption and that his intestinal problems were fully resolved. Thus did another chapter in the ever-growing legend of Mollygrubs Messer come to its conclusion.

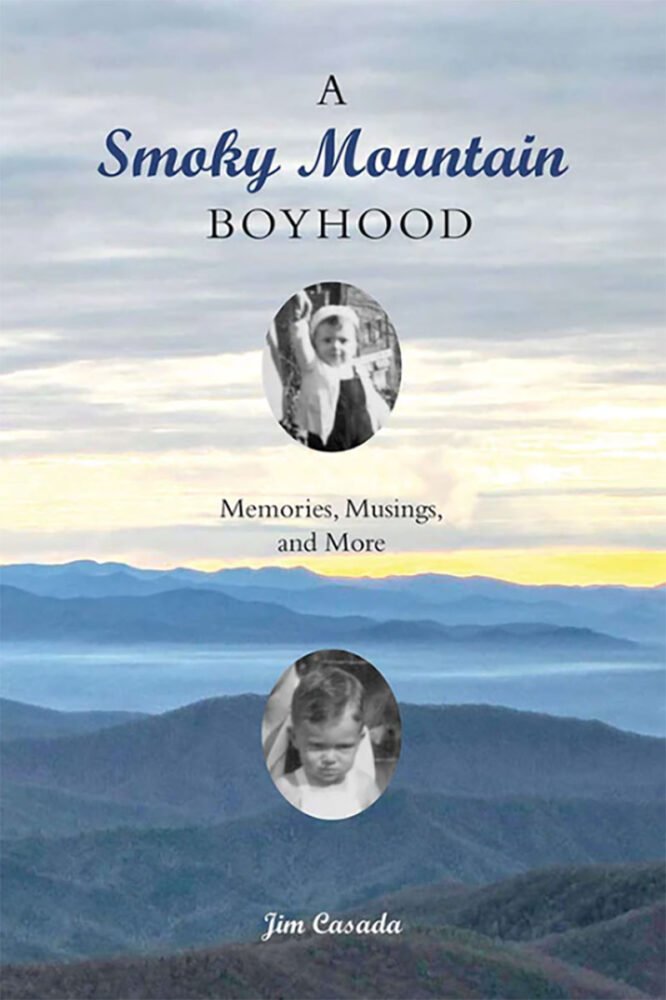

In A Smoky Mountain Boyhood, Casada pairs his gift for storytelling and his training as a historian to produce a highly readable memoir of mountain life in East Tennessee and western North Carolina. His stories evoke a strong sense of place and reflect richly on the traits that make the people of Southern Appalachia a unique American demographic. Casada discusses traditional folkways; hunting, growing, preparing, and eating wide varieties of food available in the mountain region; and the overall fabric of mountain life. Buy Now

In A Smoky Mountain Boyhood, Casada pairs his gift for storytelling and his training as a historian to produce a highly readable memoir of mountain life in East Tennessee and western North Carolina. His stories evoke a strong sense of place and reflect richly on the traits that make the people of Southern Appalachia a unique American demographic. Casada discusses traditional folkways; hunting, growing, preparing, and eating wide varieties of food available in the mountain region; and the overall fabric of mountain life. Buy Now