The Misadventures Of Mollygrubs Messer

Episode 9: Of Pointers And Polecats

Mischance, malarkey, and being the target of adolescent misfortune ran through the teenage years of Mollygrubs Messer like colorful thread binding the top of tow sacks. On one occasion, however, none of his putative buddies in the back of beyond community of Stony Lonesome, the most frequent source of pranks that plagued the lad, were in any way involved. Instead, the moment of hapless misery was one involving timeless traditions associated with a boy and his hunting dog.

All the considerable efforts of Mollygrubs’ mother, the redoubtable Mrs. “Caring Karen” Messer, notwithstanding, he grew up with considerable exposure to the long-established local custom of boys being shaped into sportsmen by their fathers or perhaps grandfathers. The senior Messer had been an avid and reasonably accomplished outdoorsman before making what he sometimes reckoned to be the mistake of a lifetime; namely, marriage to the relentless harridan and uppity social climber who had a decided penchant for making life miserable for him and the son they shared. She loathed fishing and absolutely refused to have anything to do with cooking or eating the trout that often found their way to the home during warmer months of the year. But her ultimate disdain was reserved for what she styled “blood sports.” Karen never missed an opportunity to condemn hunting as being barbaric, unbecoming of the family of a woman of her pretentious stature, and shameful to a degree that left her in a constant state of embarrassment during the fall and winter months.

Every time she saw her spouse and their son bedecked in Duxbak gear or whenever she had to walk through the enclosed porch at the back of the house that did double duty as a gun room and place to store hunting gear, a case of what she called the vapors seized her. A weekend hunting trip by the males of the household invariably left her claiming she was suffering from a migraine, although the keen observer would have noticed a miraculous recovery once they were gone. Nonetheless, if perchance they enjoyed sporting success and brought home meat for the table, the mere idea of game consumption made her take to her bed. To his credit though, the normal mollycoddle who was her husband drew the line on such matters. He would hunt, and pass on that noble tradition to his son, no matter the antics and aspersions from the distaff side of the family.

One of Herr Messer’s many efforts in that regard involved pairing Mollygrubs with various hunting partners in the form of canine companions. He felt, wisely, that an integral part of the making of a sportsman was for a boy to grow up learning the ropes of hunting alongside a dog. He was of the studied opinion that there wasn’t a lot about hunting a good dog couldn’t teach a young hunter if the latter part of the duo would only let the four-legged tracking machine’s instincts and breeding take the lead.

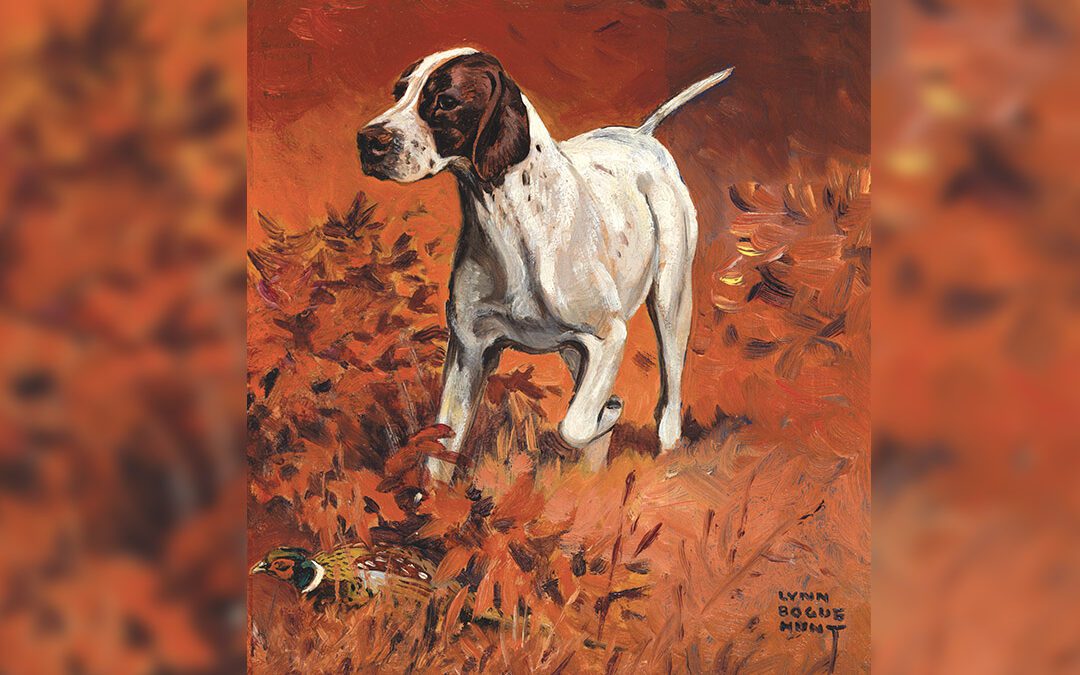

That was pretty much the background situation when, in his mid-teens, Mollygrubs became the inordinately proud owner of a bird dog. Quail and grouse hunters in Stony Lonesome didn’t pay a great deal of attention to a dog’s pedigree in terms of national registries, proper papers, kennel club certification, being at least partly “broke,” or similar concerns. They did care a great deal about blood lines, but only in the sense that they wanted a pup that came from a proven ancestry of good, solid “meat dogs.” Stylish points of the sort that made photographers drool and furnished inspiration for artists, or for that matter a canine’s physical beauty meant little. Just give a man a bird dog that found coveys, held steady to wing and shot, and maybe exerted at least modest effort when it came to retrieving, and everything was right in the world.

The pup destined to be Mollygrubs’ first pointer came from parentage, and both sides, that possessed precisely those qualities. Now Smoke, as he named the pup thanks to coloration reminding one of a hazy day in late autumn when a dry spell had led to scattered forest fires, would never have been mistaken for the kind of dog that graced the calendars put out by companies like Winchester and Remington. He was a bit too short and chunky in the body, carrying hints of a beagle in the blood line a few generations back, for a classic pointer, and his points lacked those elements of grace and style so beloved by field trial judges.

But mercy me, could Smoke point! He pointed quail with a will and showed good range when afield searching for a heady smell to be processed by a million synapses honed by a thousand generations of predecessors. He also pointed meadow larks, dickey birds, and pretty much anything else wearing feathers that would hold steady to his careful, calculated approaches. Nor were his interests and instincts limited to avians. Smoke’s repertoire included the occasional snake in early season, along with mice, moles, any ‘possum that strayed in search of persimmons while it was daytime, and on multiple occasions bits of carrion that provided the wherewithal for a good, smelly roll around when the point proved fruitless.

Mollygrubs was working assiduously, and with at least a modicum of success, to break Smoke of such undiscriminating inclinations to point anything that offered olfactory appeal. All those arduous efforts came crashing down, with the level of disaster that seemed to be his unique burden in life, on a late afternoon after-school hunt.

As was his wont from the time squirrel season opened in mid-October right through to the end of bird and rabbit season on the last day of February, Mollygrubs had rushed home from school with the home covey of birds on his mind. While out checking his rabbit gums earlier in the week he had spotted multiple fresh roost sites used by the covey, and he rightly reckoned that by late afternoon the birds would be concluding their day of wandering and feeding by easing back into that general neighborhood. Accordingly, he hurriedly changed clothes, donned his Duxbak attire, and grabbed his shotgun. Before heading to Smoke’s kennel he also paid due homage to his growing reputation as a trencherman by grabbing two biscuits left from breakfast, introduced a couple of cold sausage patties that a few months before had been part of a hog butchered the week before Thanksgiving to those “catheads” (as big biscuits were known), added a cold baked sweet potato and an apple for good measure, and then joined his erstwhile canine buddy.

Smoke, as is the nature of his kind, watered a few bushes, paying particular attention to Caring Karen’s prize roses, wallowed in the grass a bit, add some of that grass to his decidedly non-discriminating diet, and then settled down to business. For the dog, business on that particular day included a lovely find and point on a vole that had bolted back into its hole, a lone meadow lark that almost met its fate when it took wing after Mollygrubs kicked the patch of brush in the middle of the field where the point had taken place, and a false point where evidently something with an intriguing smell had recently vacated the premises.

Then came what, under other circumstances, might have been the crowning glory of a red-letter afternoon. Fifty yards ahead of his master and at the edge of the territory where his master thought it likely they might make birds, Smoke froze in a fashion that was readily distinguishable from his questionable points involved with inferior prey. Mollygrubs immediately recognized that this time his dog meant business, and he approached the holding dog in a state of heightened readiness. Miracles will happen, and when the whopping covey, maybe 25 birds in all, took wing he fired twice. A brace of birds fell to his first first shot and a third dropped a leg on his second.

Once the shock of the whole situation had been absorbed—his first time ever killing two birds with a single shot and, thanks to some stellar tracking by Smoke the location of the cripple, a three-bird tally on a covey rise—Mollygrubs was so full of himself his first inclination was to head home immediately. However, most of the covey had flown in the general direction he would need to travel to reach that destination, so in an unusual moment of common sense he reckoned it worthwhile to let Smoke work ahead of him in the gradually growing gloaming.

A sundown point, with Smoke holding in a degree of staunch steadiness that subconsciously registered on Mollygrubs with an internal message of “I’ve never seen him hold quite like that,” afforded bountiful promise of a day for the lead chapter in his personal memory’s fond book of feats afield.

With such illusions of country boy grandeur coursing through his mind, Mollygrubs moved in for the flush. When he reached what he reckoned was the right place, a thick clump of broomsedge maybe two yards across amidst a tangle of dewberry briars running along otherwise bare red clay, he kicked the waist-high golden sedge. The result was a choking cloud of noxious gas that, by comparison, made any flatulent putridity he had ever known seem almost like Chanel No. 5. Smoke had pointed a polecat and the offended party, having sought refuge without success, had done what skunks do as a sort of measure of final resort.

Both Mollygrubs and Smoke had caught the full force of Br’er Polecats singularly odiferous effusion, and the boy fled, only to fall flat of his face amidst the trip wires of dewberry briars. Once he recovered a sufficient degree of sense to find his feet, all thoughts of triumph with the bevy of birds he had killed vanished. Boy and dog stumbled home, dazed and odious beyond all measure, in search of some kind of refuge. Momma Karen Messer met them at the door, but the nasal assault on her nostrils caused the good lady to forget all about the “Caring” moniker in which she normally took great pride. She yelled “Don’t you dare come in my house!,” screamed for her husband, and then fainted dead away on the back stoop.

Multiple applications of tomato juice later in a backyard tin washtub (fortunately the day was a mild one) along with consigning heretofore perfectly good Duxbak hunting gear, along with a shirt and undergarments, to a kerosene-fed burn pile saw Mollygrubs reach a point where he was allowed in the house. Thence he was sent straight to the bathtub for more rounds of tomato juice bathing. Even then, with a most unwelcome mental harkening back to his disastrous date for the Youth Conservation Ball the previous spring, he epitomized the words of Loudon Wainwright, III’s offbeat ballad, “Dead Skunk in the Middle of the Road.” In other words, he stank “to high heaven.”

Mollygrubs spent a smelly night on the back porch rolled up in an old quilt, Smoke was in the figurative and literal dog house, and what had borne all the promise of a day to remember met that criteria—but not with the sort of memories it initially seemed to hold.

Jim Casada is the Editor at Large and Book Columnist for Sporting Classics. To learn more about his many books or subscribe to his free monthly e-newsletter, visit www.jimcasadaoutdoors.com.

A Smoky Mountain Boyhood

A Smoky Mountain Boyhood

Click Here to Buy Now

Casada discusses traditional folkways; hunting, growing, preparing, and eating wide varieties of food available in the mountain region; and the overall fabric of mountain life. Divided into four main sections—High Country Holiday Tales and Traditions; Seasons of the Smokies; Tools, Toys, and Boyhood Treasures; and Precious Memories—each part reflects on a unique and memorable coming-of-age in the Smokies.