We were out of the wind up there on that Yukon ridge. In the polished blue of the sky, fluffy white clouds were sailing along like jet planes, but where we sat, it was quiet and pleasantly warm. It was late August, the tail end of the Yukon summer, and the rolling hills around us had not yet begun to turn scarlet from the frosts. Beyond the hills in front of us, however, we could see the sawtooth profile of the St. Elias Mountains, cold and white, buried in everlasting snow and ancient ice.

“We won’t see any caribou in here,” I said grandly to my wife, Eleanor, who was making her first hunt in the Yukon.

“Ugh,” grunted little Sam Williams, an old friend and Yukon Indian guide with whom I had shot my last Dall ram back in 1956.

“Why’s that?” Eleanor asked, and without taking a breath, she said, “Let me have the binoculars.”

“Elementary, my dear,” I said. “It is too warm here. The caribou has one of the warmest coats in nature. The Indians spread their beds on caribou hides when they make brush camps in the winter at forty below. On days like this, the caribou are lying up on a snow patch or beside a very cold stream in the shade. This is no place for caribou.”

“Ugh,” said Sam.

“I’ve seen a lot of Yukon caribou in my day,” I reminisced. “Think of it! I made my first Yukon hunt back in 1945, eighteen years ago.” Then I added, “Don’t be disappointed if you don’t see any caribou today. We should see plenty before the trip is over, though.”

Eleanor had been watching something through the binoculars. Without taking them from her eyes, she said, “I’m just an innocent country girl from the Missouri Ozarks. In my day, I have seen a few deer and some javelinas, some sable and some kudu, a few leopards and lions, and things like that. I have never laid eyes on a caribou in my life. I have, however, seen on Christmas cards the pictures of the things Santa Claus uses to pull his sleigh, and if I’m not looking at three of those animals this very minute, then I’m seeing things.”

“Aw, come off it,” I said, grabbing the glasses. “This simply isn’t caribou country.”

But they were caribou—two cows and a long-legged calf. Presently, I found a fair-to-middling bull high up on the ridge and a small one down near the creek on the right.

“See those caribou?” I asked Sam.

“See ’um all the time,” he said.

“Well, Nanook of the North,” Eleanor said with a grin, “that settles that. Do you know any more interesting facts about caribou? You were just getting warmed up when we were interrupted. I simply can’t wait.”

“Watch ’um all the time,” Sam said. “Watch ’um while you talk.”

Caribou by Carl Rungius

Our patient horses had been dozing in the sun. Now we gathered them up, clambered aboard and rode down for a better look at Eleanor’s first caribou. We had the wind on them, and as with all the caribou I have ever run into, these didn’t believe anything they couldn’t smell. They saw us, jittered around. Finally, they circled to catch our wind, and when they got it, they hoisted their little white tails and took off with that long, springing gait of theirs. After running half a mile, they forgot what had frightened them and stopped to think it over. They were still up there on the brush-covered hillside when we turned our horses and headed for camp.

There were five hunters in our group, and since we had two complete outfits of cooks, cook tents, horse wranglers, and guides, we made quite an expedition. Eleanor and I had one outfit. Our cook, Babe Southwick, was an old friend who I had first met at Kluane Lake in 1945 when those pioneer Yukon outfitters, the Jacquot brothers, had outfitted Myles Brown and me for a hunt out of a base camp on Harris Creek near the Klutlan Glacier and Mount Natazhat. Our horse wrangler, Harry Dickson, was the son of Babe’s brother, Buck, who before his death had been a famous Yukon guide and outfitter. Sam Williams had guided Bill Rae, the editor of Outdoor Life, and me back in 1956, and Frank Isaac, Eleanor’s guide, was a fine sheep hunter and bush man and a very durable, as well as pleasant, character.

Our hunting companions were Bill Ruger, president of Sturm, Ruger & Company, maker of pistols, revolvers, and the Ruger carbine; Robert Chatfield-Taylor, an old friend whom I have known ever since we both lived in Arizona; and Lenard Brownell, the crack stockmaker and gunsmith from Sheridan, Wyoming.

Our outfitter was Alex Davis of Whitehorse, Yukon, who had outfitted me in 1950 and 1956. The reason for the two outfits was to enable us to travel together when the spirit moved us or split up when we thought it would be a good idea. The plan was to make two camps together and then split up temporarily to hunt Dall sheep.

The purpose of that first camp was to bring in some meat. Bill Ruger and Bob spent most of the day getting their rifles tuned up. Bob was using a .284 Winchester by Griffin and Howe on a Remington Model 700 action, a real crossbreed if I ever saw one, and Bill was armed with a .30-06 Mannlicher-Schoenauer and one of his .44-caliber carbines. Len Brownell carried a beautiful rifle of his own manufacture in .280 Remington, and this was the musket that was to start us eating fresh meat.

When we got back to camp, the evening chill had started to settle. Bob and Bill had laid out a bottle of bourbon, a pitcher of icy creek water, some crackers, and a tin of caviar on the top of a pack pannier. Both had hunted in Africa, and when Eleanor and I joined them, they were hip-deep in elephants. Len and his guide were still missing, but a rumor was circulating through camp that someone thought he had heard one shot far, far away. Maybe the old boy had connected.

And he had. Just as darkness fell and the Northern Lights began to flicker on the horizon, we heard the crunch of hooves on the boulders along the creek, and Len and his guide rode up with a very respectable bull caribou. It had indeed been a one-shot kill, Len told us. The bull was in fine shape, and with its meat we’d be living high off the caribou.

On the trail the next day we saw another caribou, a very good bull, and while the rest of us watched from the packtrain and gave our moral support, Bill Ruger and his guide went after it. I have never felt that a caribou was a very smart animal, particularly during the rut. It was getting near the time when the bulls start having romantic thoughts about the cows, but this old boy’s life was still uncomplicated. Bill and his guide, George, left the packstring and dropped down into a creek bed. Their plan was to ride up the creek out of sight, get above the bull, and have a go at him.

But the fine, old, white-necked bull, heavy horns in velvet, wasn’t having any of it. He stood for a few minutes watching the packtrain, then he turned and trotted off. The last we saw of him, he was disappearing over the skyline.

The packtrain moved on a couple of miles before we saw another bull. This time Bob Chatfield-Taylor was elected to go after him. The rest of us rode on. We had gotten to our campsite and were unpacking the horses when we heard the first high-pitched crack of Bob’s .284. I got out my binoculars and soon spotted the caribou about a mile away. Bob was shooting across the creek from the top of one cutbank at the bull, which was high on the hill above and opposite him.

Shot after shot rang out, but presently the crack of the rifle was followed by a hollow thump, and I saw the bull wobble and go down. Almost an hour later Bob and his guide came in. Bob was riding, but the guide was leading a horse laden with meat.

“Since I am a gentleman, I did not count those shots,” I told Bob.

“It’s lucky you didn’t,” he said. “At first, I thought he was farther away than he was, and then, when he got to the other side of the creek, I didn’t think he was as far as he must have been. And besides, though I hate to admit it, it’s just possible that I had a slight attack of the buck!”

I had a hard time getting Eleanor to go to bed that night, as there was a magnificent display of Northern Lights, the best we were to see on the entire trip.

We made a move the next day to the camp from which we were to hunt sheep. Eleanor and I were going to push on and camp along Isaac Creek, a stream named for the father of Frank Isaac, Eleanor’s guide. The next morning Bob Taylor took off in one direction, Len Brownell in another. Bill Ruger and his guide rode with our outfit for a time. We weren’t over four miles from camp when we saw our first sheep—a flock of at least 80 ewes and lambs feeding contentedly in a saddle between two hills. There was a high percentage of lambs to ewes, a beautiful sight, and a good omen for Yukon sheep hunting in the future.

We stopped the packtrain, dismounted, and searched the surrounding country with binoculars and spotting scope. Presently, we found some rams high on the hillside above the ewes and lambs. These were the first Dall rams Bill Ruger and Eleanor had ever seen.

While Bill and his guide went over to see if they could get a better look at the rams, Eleanor and I, with our pack outfit, headed up the valley toward the pass that led to Isaac Creek.

But we weren’t to make Isaac Creek that night. We saw some rams, one a very good one, and Eleanor decided to pass up a couple of average rams.

Out of the Canyon by Carl Rungius

The next day we made a climb and got above a bunch of rams in a basin. The best, I thought, wouldn’t go much over 37 inches, but Sam thought it might go 39. Anyway, we passed it up. To look over some more country, Sam and Frank went down a long ridge, from which they could see down onto Isaac Creek, and came back to report they had located a sow grizzly with a broken leg and two large cubs. Since the sow was near the spot where we planned to camp on Isaac Creek, and wounded grizzlies are bad medicine, both guides were apprehensive.

The next morning Sam, Eleanor, and I went out ahead of the packtrain to go over the pass, stop at the campsite, and glass the country while the outfit packed up and followed. We had just got over the top and could look down on Isaac Creek when we saw the wounded sow and her cubs. They were feeding on berries in high brush on the far side of a tributary creek. The brush averaged about as high as the backs of the bears. Sometimes it would be higher, and the bears would disappear. Sometimes it would be lower, and we could make out the tops of their backs. The sow was light-colored, and so was one of the cubs. The other cub was dark.

“Better shoot ’um old sow,” Sam said. “If you don’t shoot ’um, maybe bear get mad and kill somebody. Maybe kill horse wrangler, maybe kill guide, maybe just kill horse.”

We tied our horses out of sight, went quietly up the open ridge, and lay down. The sow was limping, no doubt of that. The two cubs were yearlings, so I was extremely reluctant to shoot the sow. In the first place, I have shot what I consider my fair share of grizzlies. In the second place, the sow looked as if she wore a summer coat, thin and coarse. In the third place, this spot struck me as just about ideal for getting into a bad go with a grizzly. The range was a little over 300 yards, too far to shoot at a dangerous animal, and the area was so brushy that I knew I probably wouldn’t get an open shot.

But Sam insisted that the safety of the party depended on my getting the sow out of our way. The cubs could make out by themselves since they had been born a year ago the previous spring, so I finally agreed to knock off the sow.

I went about ten feet ahead of Sam and Eleanor so the muzzle blast wouldn’t bother them and settled into a good prone position, with the sling high on my upper left arm. Now and then I’d catch a glimpse of one of the bears, but they were generally out of sight.

Presently I could see the back of a light-colored bear.

“Is that the sow to the right of the rock?” I asked Sam.

“Yeah, that’s her,” he said.

Holding the crosswires of the scope on my .270 just under the top of the back, I squeezed off the shot. I heard the plunk of the bullet, and the bear disappeared. An instant later the sow and one of the cubs shot out of the brush, went around the point, and were gone. Sam and I felt very foolish indeed. We had picked the wrong bear and were in an even worse situation than when we’d started, since we still had to deal with the female with the broken leg, and we might have a wounded cub. Sick at heart, I lay there watching the brush with glasses. Presently, I saw a vague movement.

“That cub’s wounded, Sam,” I said.

“Yes,” said Sam. “I see.”

“We’d better go over and get it,” I said.

“Maybe better eat lunch,” Sam said. “Maybe bear die. Maybe get sicker.”

So we ate lunch. Then I stood up.

“Well, Mama,” I said to Eleanor, “you are about to see the old meal ticket go into the brush after a wounded grizzly, but take comfort from the fact that it isn’t a very big grizzly. Hand Sam your 7mm and then sit back to enjoy the fun.”

Sam took Eleanor’s rifle, slipped a cartridge into the chamber, and put on the safety. He looked as if he were about to have a tooth extracted.

“I don’t like this one bit,” Eleanor said, “and I think the whole thing is perfectly ridiculous. Why didn’t you wait until you were sure of the bear?”

I had marked the spot where I’d last seen the bear by a spindly, little black spruce growing in the tangle of willows and arctic birch. Sam and I went down to the creek, waded it upstream from the bear, and approached as quietly as we could on the same level as the spruce.

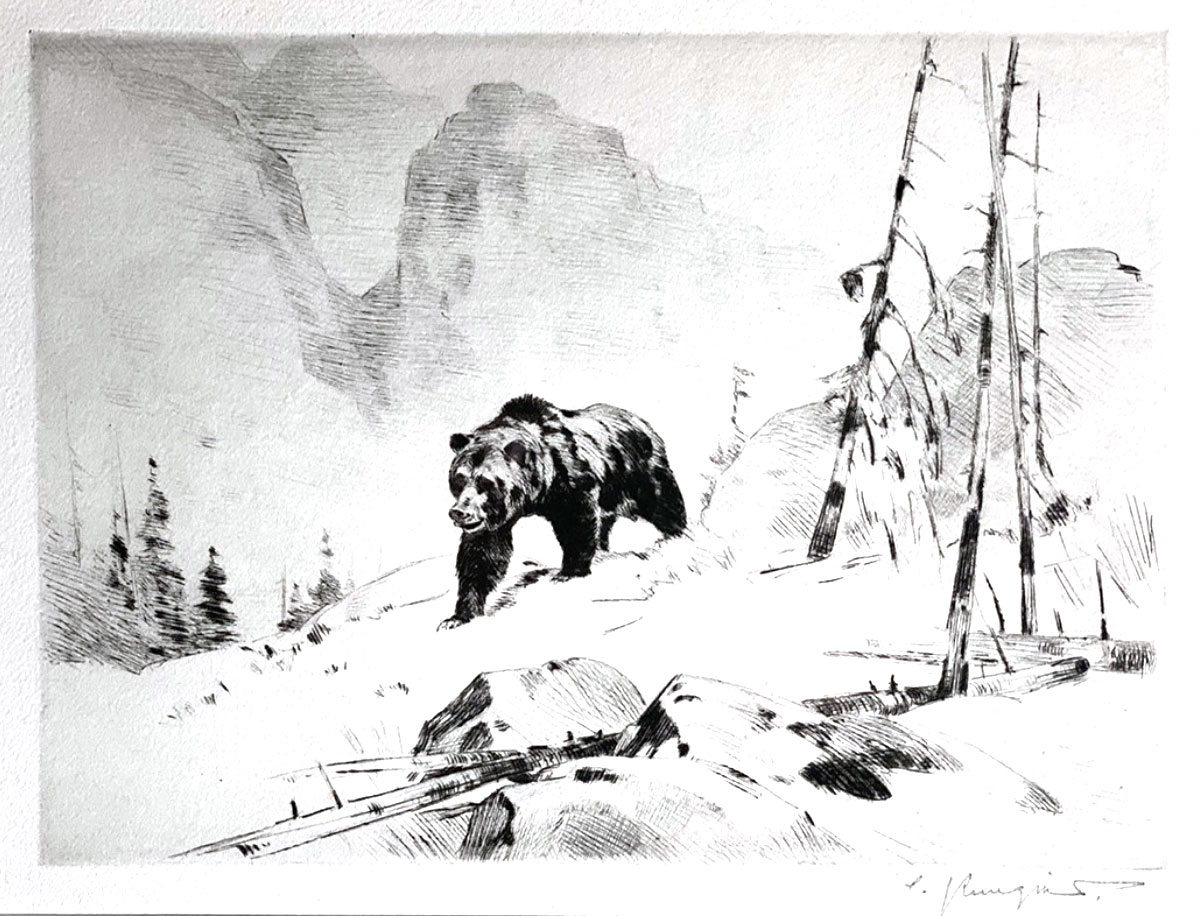

Grizzly by Carl Rungius

We were within 20 feet of the tree, carrying our rifles as if they were quail guns, when I saw a little bird fly up from a willow branch. This made the branch move, but curiously, it kept on moving. Then I saw a small patch of straw-colored hair. I put a bullet into it and heard a bawling roar. Then all was quiet.

Sam and I went around on the hillside above and, looking down, we could see the little grizzly. He was dead.

My first bullet, the strongly constructed Remington soft-point Core-Lokt, had struck very high in the lungs, but had opened up hardly at all and had gone completely through. The bear had been slowly bleeding to death internally. He had a beautiful, light-colored hide with long, fine, silky hair.

We had barely got him skinned out when the packstring appeared at the top of the pass. We fell in with them, rode down to the campsite and pitched the tents. Just before supper we saw the sow and cub once more. They were headed back to the basin where I had shot the cub. Frank and I rode up to look them over, and I decided not to shoot the sow. After looking her over carefully, I decided she was not in such bad shape. Frank told me her leg had been broken just above the foot about two weeks before by a hunter in the territory of Joe Jacquot, another outfitter, just over the ridge. It appeared to be healing, and she was putting weight on the stub. Eventually the foot would slough off. We watched her for half an hour. She was feeding and in good condition, so I thought shooting her would be both unnecessary and pointless. We never saw her or the cub again.

A week later we started to retrace our steps toward the camp where we had left our amigos. We didn’t expect to find them, since the plan had been for us to be back in five days. If we were not, they were to move on, and we would follow their trail and join them.

Eleanor and I were returning empty-handed, except for the hide of the young grizzly. We had seen no end of sheep, including a very fine one that Eleanor missed after a long and exhausting stalk. Since I had been the one who promoted the trip, I devoutly hoped that our friends had had better luck than we did.

We crossed a divide into the drainage of the next creek, then pushed on to its head and over the next divide to the spot from which we had seen the big herd of ewes and lambs in the saddle and the rams on the side of the mountain. The ewes and lambs were doing business in exactly the same stand, slowly moving along and feeding like a herd of domestic sheep. With the spotting scope we found a few young rams among them.

We went around the shoulder of the mountain about three miles from our old campsite. The binoculars showed us that the tents were still up, and we could see horses grazing. Our compadres hadn’t moved after all.

As we came jingling up, Bob and Bill came out to meet us, each with a glass in hand. They had taken the day off to spin yarns and play gin rummy, and now they were celebrating children’s hour.

“Any luck?” I asked.

“Oh brother!” said Ruger.

He pointed, and what did my wondering eyes behold but a line of trophies consisting of three sheep heads, three caribou heads, and two grizzly hides. The boys had really hit a game pocket and could hardly wait to tell me about it.

When Bill Ruger and his guide got back late that afternoon, Bob was already back with a ram. Bob is a long-range specialist who would rather knock off one head of game at 400 yards than ten at 100. He and his guide had made a long ride up the main creek and had seen two rams above them some 500 yards away. Bob looked the rams over carefully, saw that only a long and arduous stalk would bring him within range, and decided to risk a long shot. He was so far away that the rams were not unduly worried. He used his down jacket over a frost hummock as a rest, held well above the ram’s shoulder with his .284, and touched one off. He saw the ram stagger, and a moment later the plop of a striking bullet came floating back to him. Then the ram went down.

Bill got his ram the next day on the same hillside on which he had missed connections the day before. The ram was lying on an open slope but fortunately, in a depression that blocked his view of the ground above. By staying low, Bill and his guide were able to approach to within 100 yards. One shot with Bill’s .30-06 brought home the mountain mutton. Bill’s and Bob’s rams were both young fellows with curls of about 32 inches—nothing for the record book, but okay to begin on.

It had taken Len Brownell several days to get his ram, and he had passed up several before he finally saw one he wanted to stalk. Len had done a lot of bighorn hunting in his native Wyoming, and he knew what sheep hunting was all about.

One day, after a ten-mile ride, he and his guide found themselves far above timberline on a high, round top. To their right across a big canyon was a large herd of ewes and lambs and, above them, half a dozen small rams. For a time it looked as if this would be just another day.

Then they spotted three more rams far across a big canyon, lying on a ledge about halfway up a cliff. One of the rams looked quite good. They went as far as they could with their horses, then climbed the mountain and picked their way down the cliff. Len shot his unsuspecting ram at close range. It was an excellent head, with one side 39¼ inches, the best sheep he had ever taken.

Bob shot his grizzly one day, Bill the next. Both were big, mature males of which anyone would be proud. In each case the guides had discovered the grizzly two or three miles off and, fortunately, the bear had cooperated by sticking around. Bill’s bear actually was shot within sight of camp, but he and his guide had taken off in the opposite direction and had been about two miles away when they spotted it. While they were completing their stalk, the bear had lain down for the day. For a moment they thought they’d lost it, but when they sneaked up to the patch of willows where they had last seen it, the bear heard them, and when he stood up, Bill nailed him.

We made a move over to the canyon where Len had shot his ram. On the way we saw the same bunch of ewes and lambs and the same young rams that Len had seen the day he knocked off the big fellow. This was the most beautiful campsite of the entire trip—a flat bench covered with handsome trees and carpeted with soft moss and lichens. Below us was a creek, and across it was the cliffy mountainside where Len had shot his ram.

We hated to leave this lovely camp, but Eleanor and I had things to do. Because our pals had shot up just about everything edible on their licenses, the outfit was almost out of meat. So, as soon as we got our beds rolled up and our stuff stowed away in pack panniers, Eleanor and I took off with Sam for the next camp, a spot where caribou were generally found. Babe and Frank would follow with our outfit, and the others would join us in a couple of days.

There wasn’t even a semblance of a trail, and the best that could be said for our route is that by leading our horses about a third of the time and giving them their heads in the tough spots, we finally made it without any of them breaking legs. Babe and Frank didn’t show up with the outfit until after dark, but when they did, they had a tale to tell.

They had just finished packing up when George, one of the guides in the other outfit, found three rams at the foot of the cliffs where Len had shot his ram several days before. They got out the spotting scope and almost flipped. One of the rams was by far the largest any of them had seen so far—a monster that the guides agreed would go around 44 inches. Bob and Bill were ill with regret, as that enormous ram was just about cold turkey. Whoever went after it could have ridden along a trail out of sight of the ram most of the way. He could then have climbed no more than 50 yards and knocked off the ram at 150 yards.

While the others watched, Babe saddled her horse and rode after Eleanor and me, but the trail was so tough that even while pushing her horse as hard as she could, she was unable to gain on us. Finally, she gave up and went back to help Frank haze the packstring through that rugged, rocky, and brushy pass.

Everyone was still hanging around the spotting scopes, slavering over the enormous head of that fine ram. By this time Frank had decided that this was the big ram that Eleanor had missed when we were hunting out of Isaac Creek. The place where he had been shot at was only about 12 or 14 miles, as the crow flies, from the spot where he and his companions were now bedded. A frightened ram can travel a long way. Not only did this one look like the big Isaac Creek ram, but the two rams with him also looked like the same pair we had seen there.

Eleanor and I had only one day to hunt caribou, and one of us had to bring back something because Len Brownell’s ram, the last animal that had been shot, was just about eaten up. The next morning we located a bunch of caribou, including one big bull, high on a mountain about four miles away. But when we got there, the bull was gone, and try as we might, we were unable to locate him. Apparently, he had left the country. So, not long before sundown I decided to settle for a young bull. It was a very long shot, probably about 400 yards.

The next day, without knowing what was in store for us, we all rode past the mountain on which the bad luck that had haunted us was to change and Eleanor was to take the finest ram shot in the Yukon in 1963 and one of the best ever shot in North America, a monster with horns that measured 44 and 44¼ inches at the time he was shot. Some time later the head was officially taped by a Boone and Crockett Club measurer at 432/8 and 44 inches and given a score of 1774/8, good enough for 32nd place in the 1964 edition of Records of North American Big Game.

That ended the shooting, except for some bad luck for Len Brownell. He made a good stalk on a big grizzly and attempted to drive a 140-grain bullet through some brush at the grizzly’s shoulder. But no luck. The bullet either went to pieces or was deflected, and the grizzly took off in high.

A few days later we were back on the highway and headed home—Len and Bill by pickup truck loaded with hides and horns, Bob by plane straight through to the East, and Eleanor and I by plane via Juneau. I had made my first Yukon hunt 18 years before. In the meantime, those mountains had gotten a lot higher and a lot steeper. Mountains in big game country have a way of doing that when a hunter reaches his 60s. n

Editor’s Note: “A Mixed Bag in the Yukon” first appeared in the September 1965 issue of Outdoor Life.